Why Climate Impact On Tea Yield Is Making Women Workers Sick

- Purnima Sah

From skin inflammation and blurred vision to respiratory and digestive disorders, women workers in Darjeeling’s tea plantations are struggling with an array of health issues caused by daily exposure to the toxic pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers being used to combat climate impacts on the crop, shows a Behanbox investigation.

Chandrakala Chetri, 63, started working in a tea garden as a child along with her mother. Apart from plucking tea leaves at a plantation in Lepcha Busty in Tukvar village, her tasks also include spraying weed killers such as paraquat and glycel.

Chetri did not notice her body reacting to the toxic chemicals till her visions started blurring. “Every time we spray the pesticide our eyes and skin would burn and itch. One day I realised I couldn’t see the top tea leaf or white flowers from a distance. Breathing became difficult and I often vomitted during meals,” said Chetri, who recalled that her mother and grandmother too dealt with similar health issues but died undiagnosed.

Chetri’s employers do not offer their workers any protective gear or hygiene safeguards at work. The odour of the pesticide clings to her body and clothes for days after she sprays pesticides and even soap does not wash the smell off. At meal breaks, her hands still reek because there are no facilities for handwashing. “We just tie a torn dress or sack around the waist when we spray [the chemicals],” she said. “The assistant manager and the garden supervisor tell me not to work if I have problems.”

Chetri is not the only voice of distress in the tea plantations of Darjeeling. BehanBox spoke to at least 30 women from various hamlets in the district – Sepoy Dura, Gorabari, Tukvar, Singtom and Naxalbari for instance – who alleged that their health had suffered due to this constant exposure to toxic chemicals They complained of similar problems – undiagnosable skin ailments, breathing difficulty, loss of appetite, high blood pressure and stomach ache. They alleged that none of them was given any protective gear at work.

Subarna Goswami, the deputy chief medical officer (CMO) and the district’s leprosy officer, confirmed the workers’ health fears. “The life expectancy of most tea workers who visit government sub-centres is around 50 and the reason for this is their exposure to toxic chemicals at a very young age. Among the women in the reproductive age group (15-49), we see cases of uterine bleeding, cervical cancer, breast cancer, hormonal imbalance, anaemia and poor nutrition. Since early health-seeking behaviour among tea workers is extremely poor, they only visit healthcare centres [when a disease is] at an advanced stage,” he said.

Why have the plantations taken to intensive use of agrochemicals? The answer lies in climate change and its impact on this Himalayan region and its tea crop

Climate change impact

Studies on climate change in the region show that temperature rise, increase in ambient CO2 concentration and erratic rainfall events are affecting the quality and production of tea.

“Environmental factors are responsible for the development of seasonal quality [of tea leaves]. It is also a known fact that pest and disease incidence is related to the weather pattern. Therefore, temperature rise, increase in ambient CO2 concentration and extreme rainfall events (heavy rainfall and drought) brought about by climate change (global warming) can affect production and quality of tea,” says a 2013 study ‘Effect of Climate Change on Production of Darjeeling Tea’ by the Darjeeling Tea Research and Development Centre at Kurseong.

Climate change started changing the quality of the tea leaves and erratic rains and strong winds began depleting the soil, according to this centre. By 2012, green leaf productivity had declined by 41.97% compared to 1993 figures and 30.90%, compared to 2002. By 2021, according to the latest data provided by the Tea Board, the production of Darjeeling tea fell to 6.19 million, the lowest on record.

“We started noticing the change in the tea leaves quality and soil depletion 1990 onwards and we are afraid that the situation is worsening now. Soil type is depleting constantly due to erratic rains, and strong wind. We have lost the top soil that is considered very fertile for the cultivation of tea plantations. The flavour of tea is sensitive to heat, due to rise in temperature over the past three decades, the quality of Darjeeling tea has seen a decline,” said Kaushik Bhattacharjee, director of the Darjeeling Tea Research and Management Association.

The West Bengal State Action Plan Climate Change 2017-2021 too reported reduced productivity in Darjeeling tea due to erratic rainfall events that are punctuated by periods of drought.

Excessive use of agrochemicals

As we said, plantations have stepped up the use of fertilisers to compensate for the loss of soil fertility and pesticides and herbicides to deal with increased pest attacks and weed growth.

“Many tea estates have been spraying agrochemicals for years. Further, to counterbalance the negative impacts of climate change on productivity, farmers tend to increase the use of agrochemicals,” says Madhuri Nanda, director – South Asia, Rainforest Alliance, a network that has been working with Darjeeling tea estates to on forest conservation, biodiversity and climate resilience. “Darjeeling, due to favourable weather conditions in the past, has not been heavily dependent on pesticides though weeds have been the major challenge in the region. The lack of manual labour for removing weeds too is pushing some estates towards use of agrochemicals.”

However, this increased use of agrochemicals comes at a time when there is increased global demand for organic products and there have been instances of tea consignments being rejected by some countries due to their heavy pesticide content.

But plantation owners say switching completely to organic methods of cultivation – which includes replacing synthetic fertilisers and pesticides with organic versions – is untenable. The Puttabong Tukvar Tea Estate, a Jay Shree Tea & Industries Ltd. part of B.K Birla Group, set up in 1945, went organic in 2008 to cater the international demand for organic tea. But it faced losses that it has yet to recover from, said Anil Kumar Jha, the estate’s president.

“Maintaining the organic tag costs tea estates a lot, as we are not even able to cover the production cost by selling such a quality tea in the international market. Climate change has added to our woes,” said Jha.

Only half of Darjeeling’s tea plantations are organic at the moment and in 2019, only 30% of the tea the country produced was inorganic – 400 million kg of 1.340 million kg, estimated Sandeep Mukherjee, principal advisor of the Darjeeling Tea Association. “Going organic doesn’t make much sense, especially for gardens that sell locally because among domestic growers and consumers, there is not enough awareness about organic vs inorganic ,” he pointed out.

“The soil composition has changed so much that going back is impossible and unaffordable,” he said, adding that the chemical pesticides and insecticides used in tea gardens are carcinogenic in nature. “The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India is supposed to regulate, check and test before tea is released in the market, but they don’t do so.”

Reckless use of deadly glyphosate

Soil microbes in a land abused with pesticides could take at least two decades to recover their characteristics. Current pesticide usage is beyond the soil and plant’s carrying capacity resulting in residual amounts of harmful chemicals in the leaves and soil and this could cause neurological disease in those who handle the soil or plants, said Malay Bhattacharya of the department of tea science at the University of North Bengal.

“When a pesticide is sprayed, the microflora of the ground such as bacteria and fungus that maintain the soil fertility either die or change to survive. The microbes turn deadly over a period of time and as the pesticide content increases so does their tolerance level. Those that can’t take the chemicals, crawl out of the soil. For example, a fungus, fuzarium, comes out of the soil and feeds on tea leaves to survive and they are killed by spraying fungicide,” he said.

The Tea Research Institute claims that the acaricides (a pesticide that kills mites and ticks), insecticides, fungicide, herbicides and bio-pesticides used in the plantations have been cleared and registered by the government’s Central Insecticides Board and Registration Committee.

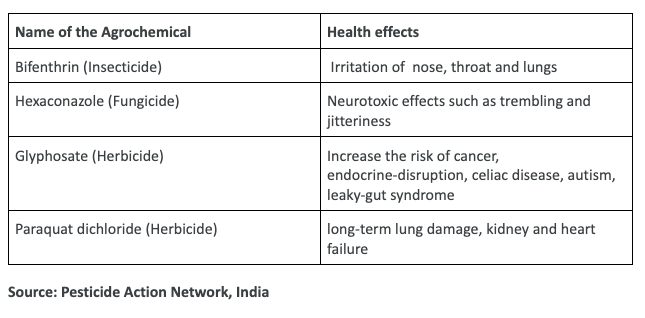

But among these are many pesticides that are deadly for humans as well. Pyridaben, a pesticide, has been reported to have detrimental effects on the neurons, hormonal balance and embryonic development. Another pesticide, propargite too is harmful and it can be inhaled or absorbed through the skin.

Let us take the case of glyphosate, a highly toxic herbicide, with long and short term health outcomes. Glyphosate use is severely restricted in over 35 countries, including Sri Lanka, Netherlands, France, Colombia, Canada, Israel and Argentina. However, the Anupam Varma Committee constituted by the Ministry of Agriculture in 2013 with the mandate to review pesticide usage – including those banned or restricted in other countries and still used in India – did not include glyphosate for review, said Narasimha Reddy, director, Pesticide Action Network India (PAN India), a public interest research and advocacy non-profit organisation.

In India, glyphosate’s use is approved only for weed control in tea plantations and non-plantation areas accompanying the tea crop. But it is used with little monitoring or control across farms and plantations: a 2017 field study in seven states — Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and West Bengal – reported a April 2020 study titled ‘Highly Hazardous Pesticide Series-State of Glyphosate Use in India‘ by PAN India. Upto 77.97% of the farmers surveyed reported glyphosate usage.

Unintended uses of glyphosate were widely observed in the study, with more than 20 non-approved uses for food and non-food crops. PAN India concluded that this pesticide’s use has soared in recent years due to the increased cultivation of genetically modified crops and labour shortages.

Respondents to the PAN study who had been exposed to glyphosate reported nausea, vomiting, dysentery, headache, fever, skin fissures, increased heart rate, eye irritation, urinary infections and so on. While it is being mixed and sprayed it could spill on to exposed skin on legs, arms and other parts of the body especially if the spraying equipment is faulty.

Over 60% of glyphosate users had not been trained in its use or the safety measures needed for handling it. The warning statements and some safety instructions on the labels were inadequate and there were no instructions on the use of PPE, except gloves, as prescribed by the Insecticide Rules 1971, said the report.

No facilities for diagnosis, research

We spoke to veteran frontline health workers who reported seeing several patients with complaints about high blood pressure, respiratory, gastric and skin problems among plantation workers.

Patients have queued up at the Sepoy Dhura’s dispensary and most are aged between early 20s and 50s. “Many come with acute breathing difficulty, we send them to Kurseong as we are not equipped to treat serious cases. The stock of medicines comes once a year,” said Asha Rai, a health worker who has been working at the dispensary for 11 years. This was echoed by nurse Devika Rai from the Tukvar third division dispensary.

Chandra Thapa, 56, from Sukhia Pokhari has been working in tea gardens since 15. She has carried and sprayed heavy jars of pesticides. “I have touched those fertilisers with bare hands and mixed them in water. My skin and eyes would burn, I lost my appetite, and felt breathless all the time. In tea gardens, we are seen as manual labourers and nobody cares for our grievances. My clothes reeked of their smell for weeks,” she said.

The first effect of chemical exposure shows up on the skin. “The infection seems fungal initially and sometimes like cut marks or wounds. Chemical-based fertilisers and pesticides cause renal and skin disease including skin cancer. Most of the skin diseases are unknown to medical professionals as they are not studied and investigated yet,” said deputy CMO Goswami.

We heard similar complaints from other workers such as 69-year-old Subhalakshi Rai from Bhotat Basti in Sepoy Dura, who has to deal with severe skin irritation, “burning nose”, and blurred vision. A couple, Nirmala and Rupeshr Tamanag from Daragaon hamlet in Tukvar, said they experienced similar symptoms along with nausea, stomach ache and diarrhoea. Aruna Tamang from Sonada lost her mother to acute breathing difficulty, and multiple women tea pickers from Naxalbari are living with undiagnosed skin and respiratory ailments.

Doctors also complained that with few health centres in Siliguri or Kolkata facilitating disease investigation and research, it is hard to study, identify and diagnose these problems.

Another health impact of climate change is the spread of scrub typhus, a skin disease caused by a bacteria transmitted through the bite of mites, in the region, said Subhasis Chanda, superintendent at the Darjeeling District Hospital. The transmission of the disease has been hastened by climate change, it has been established. “Patients only come when it spreads all over the body and most of the time they die. When we were at medical school, scrub typhus was said to be very uncommon in India,” said Chanda.

‘Can’t invest in health: managers’

Deputy CMO Goswami says his efforts to improve conditions in West Bengal’s tea gardens have met with resistance. He alleged that he has been transferred seven times in just 10 years of his service in different tea gardens of West Bengal.

Goswami said he has shared his anxieties about the health of tea workers with the owners and their managers and found no response. “The managers always repeat they are incurring loss and can’t invest in healthcare. This is their legal responsibility but for years it’s been overlooked,” he stressed.

The Darjeeling-based NGO, Federation of Societies for Environmental Protection (FOCEP), has been writing to the state and central environment authorities since 1989 against the rampant usage of pesticides in the hills but with no result.

“In 2017, the villagers of Tukvar were worried when they saw moths, honeybees and other tiny insects fall dead in the tea gardens. We found that the shade trees in the tea gardens were taped with a yellow chemical paste as a part of a mass pest-cleaning drive by the Tukvar tea management. The district forest officer warned the manager, and we also explained [to the manager] the adverse effects of it [the paste] on the environment. They assured us they would not repeat the practice but it happens even today,” said FOCEP secretary, Bharat Prakash Rai.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.