In Tribal UP, School-Girls As Well As Graduates Are Driven To Construction Work

- Neetu Singh

It is a wintery February morning and a dense fog has descended over Palia, a town 100 km from Lakhimpur town in northern Uttar Pradesh’s Lakhimpur Kheri district. At a busy construction site, many girls and women are at work, carrying bricks and mortar on their head, some are hammering the bricks into small bits.

There are girls as young as 14-15 years old working here carrying headloads too heavy for their slight bodies. As the day ends, the girls and women line up for their daily wage – Rs 250-300. We speak to the women and girls and find that some have barely finished primary school, others are still studying. And a miniscule number are graduates.

There is one thing that connects many of them – they are Tharus, Adivasis inhabiting the Terai (foothills) districts of the state along the lower Himalayas. This community, known for its distinct culture, can also be found across the border in southern Nepal and in the forested border regions of Shravasti and Bahraich districts.

Adivasis are India’s poorest people, with half the population living in the lowest wealth bracket. Development plans and welfare schemes reach barely 10% of them. For example, so poor is the reach of the nutrition interventions in these pockets that 32% of tribal women are chronically undernourished, as opposed to 23% among other populations.

The Tharus are UP’s largest tribal community and they are mostly forest-dwellers, wage workers or farmers of whom about 70% are marginal, as per a 2019 study. About 33.5% of their population earn a monthly income of Rs 5000-Rs 15000. A large part of the burden of poverty falls on the women and girls, such as the Class 11 student at the construction site who did not want to be named.

“I cleared Class 10 this year and am studying for Class 11. I work to pay my school fees. Summer, winter, rain, I work from 8am to 5pm while my parents work in the fields. We all have to work because everything is so expensive,” said the young woman hammering bricks, her face veiled to keep off dust and, she said, to avoid being recognised. “I hate this work and if my relatives see what I am doing despite my education….”

Why the youngster was driven to manual labour in her mid-teens became apparent to us as we traversed eight Tharu villages over 12 days. We found that the community has hardly any access to public services, facilities and infrastructure. In some places, roads are non-existent and in Soorma panchayat for example, you have to walk through forests to reach five villages. The one primary health centre in Tharuhat in Lakhimpur has a big lock at the entrance, and residents said they have not seen a doctor in years – if and when it opens, the ward boys run it.

UP’s employment crisis

Rewati Rana, 25, who was carrying bricks across the construction site, is a rare woman graduate in the area. But so acute is the problem of unemployment that she has resigned herself to a life of manual work. “I used to travel 30 km, across forests, to reach my college in Palia for my BA. But I have ended up doing this work to feed my two children,” she said.

UP, currently in the midst of a seven-phase assembly election, is facing a post-pandemic unemployment problem. Its employment rate has fallen from 38.4% in 2016 to 33% in August 2021. The Yogi Adityanath government took charge in April 2017, and since then the working-age population has grown by over 12% while the number of people with jobs grew by just 0.2%.

The CM has claimed that in his five-year tenure, the government has provided 450,000 government jobs, that hundreds of thousands are now self-employed and that job opportunities have been opened up despite the pandemic. But there is nothing in the Tharu belt to show for this.

All the parties contesting the ongoing elections have promised employment if they are voted to power. The Samajwadi Party has promised 2.2 million IT jobs; the BJP talks of at least one job per family and the Congress has pledged 2 million jobs in different sectors. Will these promises be realised, especially in neglected corners of the state? Current realities in Tharu do not offer much hope.

The unemployment rate amongst UP’s women stands at 25.8%. And backward regions like the Tharu belt show the extent of this desperation. Here, women work all day, caught in a relentless cycle of care work, domestic chores and backbreaking farm work.

Five of six schools shut

About 50-60 girls in Masaha village of Motipur panchayat, 40km from Shravasti, work at construction sites, said Manju Rana, 22, who started working after Class 8 to help her family. Education is a low priority among most farming families of the area which reports a lot of human-wildlife conflict. While the adults farm and guard their fields, children are expected to look after their homes and siblings. And those like Manju who do start school often struggle to pay their fees and help their families survive.

“Girls from rich families study and girls from poor families bring home the money they earn from labour work. Who doesn’t wish to study but we can study only if we get that chance. It will be hard to keep the kitchen fires going if we stop earning,” she said, choking in distress. “We used to get Rs 50 per day then. I could only go twice to study at school in two months, the rest of the days were spent in labour work. I had to leave my studies because what else could I have done?”

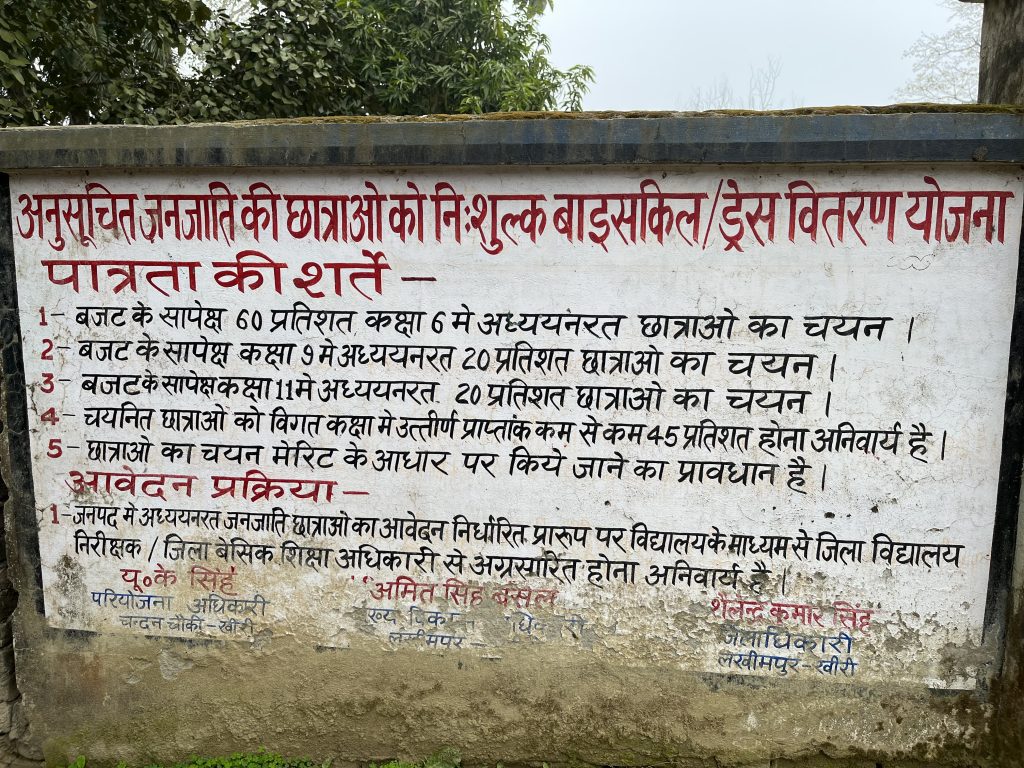

Female literacy among Scheduled Tribes stands at a national average of 49.4% and in UP at 43.7%. On paper, the administration is doing a lot to skill and educate the youth, especially girls, as per the office of the Integrated Tribal Development Programme office in Chandan Chowki in Tharuhat. The office reports an annual allocation of Rs 12 lakh for cycles and Rs 2.5 lakh for books to encourage girls to study further.

There is a scheme to educate women and train them in skills such as tailoring for six months wherein they get a stipend and a toolkit thereafter. Meritorious girl students are entitled to Rs 3000 for the purchase of a cycle and Rs 700 for uniforms. As per 2021-22 figures, 148 girls from Classes 9 and 10 got free school books. There are high school scholarships for students whose parents live below an annual income of Rs 2.5 lakh a year. There are also residential schools, book banks and libraries.

Why schemes fail

The transformation these schemes promise is not visible anywhere in the Tharu belt. And the reasons are not far to seek. The primary education system is in tatters. Take for example Tharuhat – of its six primary schools, five are closed for want of staff. Mohanlal Tripathi, a senior accountant in the Integrated Tribal Development Programme, complained of acute staff shortages.

“Because of the shortage of staff, five primary schools had to be shut down. At the moment, 111 staff positions are vacant. We have written [to state authorities] several times but no one paid any attention. We have also sent a petition to the district magistrate. At the moment there are just 14 staff members, which is not enough. If we got the necessary human resources, we would work better,” said Tripathi.

There is also a training centre for skill development for women but that too is not working. “This building was ready and we were meant to train women and girls as beauticians, and impart skills in sewing, computer work and handicrafts. But when we completed all the formalities, the electoral model code of conduct kicked in and the centre remains non-operational,” Tripathi said.

Rajnish Gambhir, national secretary of the All India Union of Forest Working People (AIUFWP), an union working on tribal rights, said a multitude of public schemes for tribal communities means nothing when they do not reach their targets. The problem is implementation and corruption, he said. “It took Soorma 33 years of struggle to be classified as a revenue village in 2011 but it has yet to get roads or electricity,” he pointed out. “And the literacy and livelihood schemes for women are so shoddily implemented that the quality of education is too poor to get them good jobs.”

‘What choice do we have?’

In the ongoing elections in the state, women have been at the heart of the campaigns of all political parties – the number of voters has been increasing steadily in the state and this time 70 million women will be voting. Upto 40% of the candidates picked by the Congress are women, the BJP has been running a campaign claiming empowerment of women during the Yogi regime and the Samajwadi Party has promised women 33% reservation in government jobs.

But people like the Tharus matter little in the electoral jousting. “We are too few in number to figure on manifestos. Even if they ignore us but give us forest rights we could have improved our lot but we are landless and helpless. What can the girls do except pitch in and help their families?” said Sahvania Rana, national secretary of AIUFWP.

It is routine for Tharu girls in their teens to leave home for brief periods in search of work. For example, Manju and her friends head for the construction sites of Lucknow, Gonda and Lakhimpur for 10-15 days of casual work whenever their families are in distress. And this was the case with her uncle’s daughters too, she said.

“Wherever there is work, the contractor takes a group of women. At night, we would build a makeshift tarpaulin shed to live in. If we rest we are abused so we keep working like slaves. Sometimes contractors don’t even pay,” she said, dismissing our questions about the hardship of carrying a load as a young teen. “We all do it. There is no choice.”

As per the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, 14.9% graduates in UP are in search of jobs. Rewati Rana is one of them.

“”I thought I would get an office job once I had a degree,” she said. “Everyone used to say that Tharu Adivasis get jobs through [ST] quota [for government jobs], but I did not get one. We don’t need free rations, we need jobs.”

In Masaha, dozens of educated women work as brick kiln labourers because they have no other means of employment. Vimala Rana , 19, is one of them who is in the midst of preparing for her BA final year exams. “From the time I started studying in Class 10 to now, I have spent most of my days doing labour work,” she said.

Unemployment and exhausting hard work are not the only difficulties women labourers face. They also have to deal with misbehaviour of contractors and employers. “(We) Endure slavery with our lips sealed. The slightest negligence and we lose our jobs. At times, family members accompany us but mostly, we go with other girls. We are scared but nothing can be done,” said Vimala.

For women like Geeta Devi, 35, who has been doing wage work for the last 14 years there is no hope of a better tomorrow. “I can work as long as my body allows me to. What will I do when I grow old?” she asked. She lost her husband in an accident at work 14 years ago. “Many died doing this work. There is no count. I travel 20-22 km to Palia everyday with my young son. If I don’t work, what will I eat?”

It has been widely reported that unskilled women labourers including those in construction work face multiple issues from wage discrimination to sexual harassment. But the Tharu women we spoke to said they prefer this work to farm labour if they are in dire need of money – at Rs 50-100 it pays better.

The women are not open about voicing their concerns about safety issues but point to the risk of sending young girls across long distances to work. “ If the contractor raises his voice, I shudder. I sent my 14-year-old daughter to work only out of compulsion,” said Sukhni, 37, whose husband died when he fell off the electric pole he was working on. “My family of three kids and a disabled husband depends on my wage. So I have to send my child to work. We have arranged her marriage to a family but they are also poor and landless. She will have to toil there as well. I think her whole life will pass by, lifting bricks.”

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.