‘We Live, Work In Filth And Are Treated Like Filth:’ Punjab’s Dalit Women Caught In Cycle Of Bonded Work

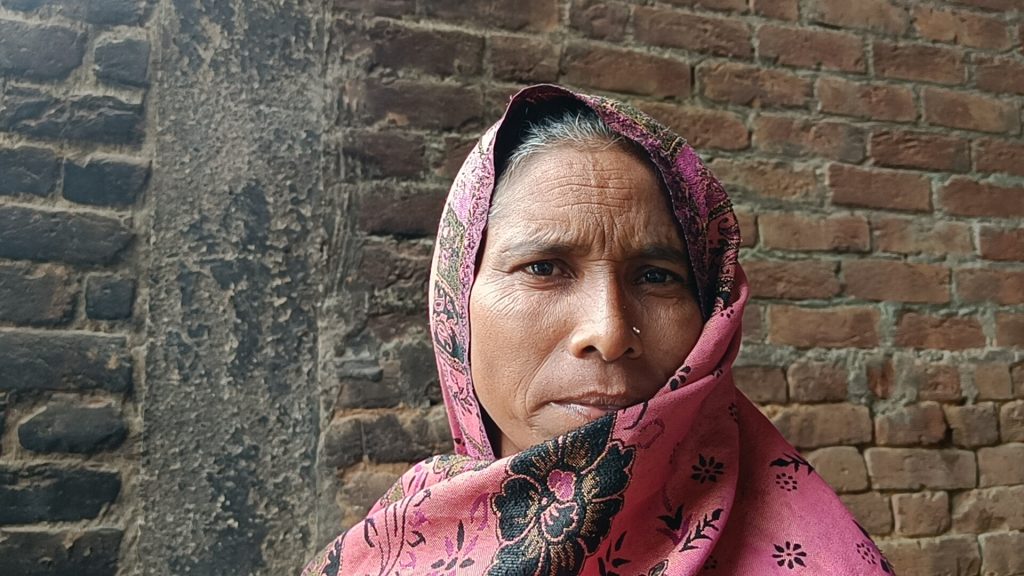

Tej Kaur, a Dalit Sikh , has been cleaning and collecting cow dung for 30 years. Her walk is steady but the strain and struggle of working as a siri (bonded worker) for decades are visible on her. She is just over 60, but the wrinkles and wispy grey hair make her seem much older.

“I’ve grown old in the goha (dung),” said Tej, the oldest goha-kura wali (dung scavenger) in Budhlata, a village in Ahmedpur block of Mansa district in southern Punjab. She was in her late 20s when her husband, a farm labourer who too worked as a siri for a landowning family in the village, lost a hand while using a chara machine (chaff cutter). With no means to sustain the family, Tej Kaur took up dung cleaning work.

When the medical bills started piling up, Tej Kaur borrowed Rs 10,000 from an upper-caste Jat landowner who was known for giving loans to Budhlata’s farm workers. The interest rate was so usurious that Tej had to start doing goha work for the lender’s family at paltry wages. But it was never enough. Soon, she had to borrow further to repay the loan and survive. This meant taking on more goha work at the homes of her landowner-creditors.

The debt trap had been set in motion for Tej Kaur, and so was a life-time of bonded labour, the burden of which all the women in her family have shared.

Tej’s story is not uncommon in Budhlata. We found several Dalit women in the village entangled in old debts, some as low as Rs 300 borrowed to buy medicines. They work in inhuman conditions, often putting in two shifts per house to manage the workload. The richer households have 7-8 cows and the women end up lifting as much as 10kg of dung a day. Every trip to dump the dung in the fields is a half kilometer trudge. And for all this work, they are paid no more than Rs 300-500 a month per household.

Missing a shift or a day’s work is not an option, the women told BehanBox. If they do, a family member – always a woman because men will not handle this task – has to step in as replacement or else their wages are docked arbitrarily. And then there are the indignities and abuse they are subjected to.

Dung cleaning is taken on only by the women of two stigmatised castes in Punjab – the Ramdasias and the Mazhabi Sikhs, both communities that descended from scavenger families. Those doing goha work are mostly Mazhabi Sikhs.

A 2019 survey of rural Punjab’s women labourers in Malwa, Doaba and Majha regions led by agricultural economist Gian Singh showed that 92% were Dalits, and 7% Other Backwards Classes. Only around 1% hailed from the general category, and they did not touch cleaning work.

The study, now a book Socio-Economic Conditions And Political Participation Of Rural Woman Labourers In Punjab, points to the oppressive debt load borne by women in rural Punjab — 93.71% of households with woman farm labourers are under debt and the average debt amount per indebted household was Rs. 57537.28. This is not surprising because the maximum proportion of debts (33.9%) were given at interest rates of 36% and upwards, said the study.

Why is indebtedness so common among rural women labourers? The average per capita income of the rural woman labour households is Rs. 16584.46, too little to cover even basic needs and pushing the women into debt, the study reported. An average rural woman labour household in Punjab owes Rs. 43678.99 to non-institutional sources and Rs.10237.46 to institutional sources. It is the large farmers and landlords that provide the highest amount (Rs.16083.28) to the average rural woman labour household, showing the grip of the land owning class on poor families.

Land ownership and caste

Acute economic inequalities and caste discrimination are rampant in Punjab’s agrarian ecosystem, show studies. Consider the figures from the 2015-16 Agricultural Census: upper-caste Jat Sikhs own most farmlands and in massive swathes – at 5.28%, Punjab has the most number of big farmers owning more than 10 hectares of land anywhere in India except in the non-mountainous states. The national average is 0.57%. However, Dalits, who make for 32% of the state’s population, own only 3.5% of farmlands. The national average though is 8.6% of agricultural lands for 16.6% of Dalits.

These divisions are visible in Malwa’s villages which produce mostly rice, wheat, moong and mustard. It is home to Punjab’s biggest farm union, the Bharti Kisah Union (Ekta-Ugrahan) and its farmers have been at the forefront of the long-drawn farmers’ protest against new farm laws that were ultimately withdrawn by the government. But it also reports the highest farm suicide rate in the state: upto 97% of the 3,300 farmer suicides in Punjab in 2000–2019 were reported from just from Malwa.

The links between caste and bonded labour are common in many parts of India. It is one of the foundations of the bonded labour system in agriculture as well as other industries, said the India Exclusion Report, published in 2013-14 by the Centre for Equity Studies. The lack of land ownership, combined with the expectation to free or minimally paid labour and the threat of violence and economic boycott against those who challenge the social order, keeps many Dalit families in bondage and in a perpetual state of poverty, it said.

Caste discrimination against Dalits is still rampant despite the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 that has declared it punishable to compel someone from the Scheduled Caste community to work as bonded labour.

Exactly how do we define bonded labour? Dilraj Singh, policy analyst and lawyer, Punjab and Haryana High Court, Chandigarh, cites the law: “Anyone who is completely or partially forced to work under an employer who lends a loan with interest to his/ her labourer and in lieu of that loan, extracts labour for unspecified period without payment of wages or on reduced wages, follows the ‘Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976’.”

However, experts have asked that with the nature of bonded labour changing, it has become critical to redefine it – to not regard debt as a mandatory component of bonded labour but also include the non-payment of minimum wage against an advance or debt, impose restraint on physical liberty or the right to change employment or forcibly prevent labour from realising its full market value.

The law has also not dealt with the need to address the enabling social and economic conditions that make bondage possible, largely because states tend to deny the existence of bondage and there is poor identification, says the Exclusion report.

In Malwa, these factors are visibly at play, including the social boycott of those who choose to break the bond of labour, as we detail later.

Six jobs, two shifts, Rs 3000 a month in all

Bonded labour is common in the Malwa region, said Gian Singh, who retired as a professor of economics from the Punjabi University at Patiala. “Farmers and landowners give loans to labourers at a high rate of interest ensuring that they stay bonded to them their entire life,” he said.

Most women in Budhlata make barely Rs 3,000 a month and that too by taking on at least six jobs and their earnings go into food, medical expenses and the cost of maintaining their kucha homes. The wages are so sparse that the women often agree to being paid with a meal, served, they say, with no respect for their dignity.

“In one house, I do get chai, obviously a separate cup is dedicated to me there which has no handle. I also get roti every now and then, depending on if they have the left overs remaining,” said Tej Kaur.

Parmeet Kaur, 56, who has done cleaning work for 30 years, complained of humiliating treatment at the hands of her employers too. Her husband is too old to work so her two children, both graduates, pitch in. If anyone falls sick, a medical bill of Rs 1000 is enough to set off another financial crisis in the household. “Add to that food, other rations, and prices touching sky high,” she said, explaining why she works in the homes of 10 creditors.

Then there is the lack of respect. “They give us basi-roti (leftovers or stale food). I can’t say no because that is the only thing I get to eat for lunch,” said Parmeet. “I leave for work at six in the morning and return home at around five. If I don’t report any day, they deduct Rs 300. They claim they had to call someone else to do the job and pay much more for the same work.”

The workers get no leave and have to work on Sunday. Even if they are sick they go to work. “Someone from the kothi would come and yell at us to come and do the cleaning. We shiver in the cold, get drenched during the rains, get sunstroke in summers – but we never get any leave. The work has to be done anyhow,” Parrmeet said.

The grip of the landowning upper caste families on the rural economy is also entrenched through social networks. The rules of hierarchy and bondage are so strong that no woman we interviewed was willing to name her employer for fear or reprisal.

Three generations at scavenging work

It was evident in Budhlata that bonded work, exploitation and stigma are all transgenerational. Not only Tej Kaur but her daughter-in-law and school-going daughter, all have to pitch in with scavenging, to keep the family afloat.

Till Paramjeet, 35, married into Tej Kaur’s family, she had never done any kind of farm work. But she soon realised that she would have to join her mother-in-law at goha cleaning. “Only, after I came to my in-laws, I realised I need to do what my mother-in-law has been doing because how else would we make ends meet,” she said.

Now, Paramjeet and her family live separately but she has her own loans to repay so she continues with the dung cleaning work. She works in five houses. “But I earn nothing because my earnings are adjusted against the principal amount, Rs 15,000, every month and I can never quit working in these houses till I am debt-free. The 500 Rs I earn from each house, gets deducted as the monthly instalment to my malik (employer),” said Paramjeet. “For each day we miss work, the malik deducts Rs 200-300.”

But the replacement worker is never paid more than Rs 50 for a day’s labour, we were told.

Every single woman and girl of a Dalit family engaged in goha work – this is a common sight in the villages, said Gangandeep, a Jalandhar-based lawyer and president of the Dalit Dastan Virodhi Andolan, who has been working for Dalits and labourers in Punjab for over a decade now. “I know many such families. It happens automatically: when a working woman takes leave, her daughter or younger sister would clean cow-dung on their behalf. Then age and a series of loans compel the younger generation to step into the world of goha. And then, there is no going back,” said the activist who prefers to go by her first name.

On days when Paramjeet finds it hard to get to work, she sends her 16-year-old daughter, Harpreet, instead. “When I am sick, or on my period or any other emergency at home, I send my daughter to work on my behalf. We can’t afford to lose half a month’s salary in one day,” she said.

Harpreet, 16, goes to the nearest government school and would like to continue studying. She has seen her grandmother and mother engage in goha kura work and wants to end this bondage for good. “Mai bade hokar maa-baap da naam roshan karna chauniya par mai mere maa naal jake bhi goha-kura kardiyan (I want to make my parents proud when I grow up, but I also have to help my mother collect cow-dung),” said Harpreet, who is Paramjeet’s only daughter. “I appeal to the next government in the state to provide better education and job opportunities to girls like me who are helping their parents make ends meet.”

‘We are used to filth, treated like filth’

Punjab has a literacy gap that is both gender and caste-driven, putting Dalit women at the worst disadvantage. Overall literacy among Dalits is 64.81%, the female literacy rate is 58.39% and male 70.66%. Gian Singh’s study found that more than two-thirds of the rural woman labourers surveyed (67.35%) were illiterate. Only 32.65% have some kind of formal school education. The report also states that not even a single woman labourer in the sample had studied upto graduation.

The literacy rate of Mansa district shows a gender gap – 68.4% literate males against 56.4% women.

Poor literacy and the lack of empowerment that education could bring are important reasons why the culture of bonded work never loses its grip in the area, said Naina Sharma, principal incharge at the University College in Ghanour, Patiala. “Dalit women have been in this goha kura business for ages now while their men would work as labourers. They are so rooted in the idea that they do not speak up for themselves or oppose the exploitation they face on a regular basis at work. The low literacy rate, caste issues, gender and the overall intersectionality of all these factors keep pulling them into a bog,” she said.

Kirna, 30, from Budhlata has been doing goha kura work for a decade now and the edges of her nails are dark brown with the dung seeping into her cuticles. The work involves not just mopping up the dung, but also patting it into cakes and cleaning cattlesheds. “The stain doesn’t go when you have to clear dung every single day. It doesn’t even matter. We are used to filth and being called filthy by our upper-caste employers,” she said.

There are other indignities. “You might not believe it but the employers never call the women by their names but refer to them by their caste, mostly choodi (Punjabi for chamar or scavenger),” said Gagandeep. (Addressing a Dalit or Adivasi in such terms is considered an “offence of atrocities against members of SCs and STs”.)

Kirna has always worked for three households but she adds more to her workload when she needs money. “I took a loan from the three Jat Sikh landowners to get my house repaired before monsoon and once to pay for a medical emergency. With a monthly earning of Rs 2500 from five houses one can barely afford two meals a day for a family of five. For urgent needs I take small loans of Rs 200-500 from one of my employers and this is deducted from my next salary, both the principal and the interest,” she said.

Kirna mentions about her ongoing loan payment in detail. “I had taken 10,000 as a loan and I had to pay back 13,000, including the interest. We pay back in very small installments which is why the interest rate is higher.”

Social boycott for attempting escape

Jagseer Singh, secretary of Volunteer for Social Justice, a non-profit organisation, has been working in the Malwa region for about a decade now and these stories of exploitation are familiar to him. “Mansa and Bathinda have many such families where women have been grabbed for cheap labour in exchange for tiny loans that they keep trying to repay for years,” he said.

Why do the Dalit women find it hard to escape this bondage and take up more remunerative options such as farm work? After all, the annual average of daily wages for a female field worker putting in eight hours of work is Rs 349 and men Rs 425 in Punjab, as per this 2019-20 government report. The answer lies in an array of factors that are both economic and social.

Kirna said she would be happy to work as a daily wage labourer elsewhere but she has yet to repay her debt of Rs 10,000 to three employers. “Our salary should increase to at least Rs 1000 per month for all the toiling we do and filth we stay in,” Kirna tells BehanBox. “But who will listen to us? I could have made three or four times more as a farm worker but with the repayment still pending, my employer would never let me go nor can I risk my life opposing them.”

Gagandeep said the landowning network ensures that the women do not have any avenues of escape because no one else but Dalit women are willing to take on the cleaning work at nominal wages. Landowner-creditors also use socially repressive measures to make escape impossible.

“If any woman leaves work due to loan, debt or any other outrage at work, the employer ensures they do not get work anywhere else in the village. The women then won’t just face social and economical boycotts in the village but there would also be an announcement in the local gurudwara to the effect that ‘this particular woman should not get work in the village because she left mine’. The village shops won’t sell them anything and they are banned from community wells and taps,” the lawyer-activist said.

We spoke to Shinderpal Kaur, one of the Jat Sikh landowners in Bathinda who claimed that she pays Rs 200 per animal to her goha worker. The 60-year-old has four cows and three buffaloes. “I have seven so I pay 1400 a month and also give her half-litre milk everyday. That is how almost everyone here pays,” she said.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.