‘We Are Harassed, Beaten’: Adivasi Women Who Demand Forest Land Rights In Gujarat

“Ye pitai khayi hui auratein hain (These are the women who’ve got beaten up).” That is how we are introduced to Nandaben Nayak, Navliben Nayak and Kamlaben Nayak, all in their 50s, in Devalikuan village in Gujarat’s Dahod district. The dramatic description elicits peels of laughter from the women standing around.

The Nayak women are all from the Bhil Adivasi community in southern Gujarat and they were allegedly beaten up by forest officials for shielding their husbands, accused of claiming ownership of land in the village without any documentary evidence. This tussle has been at the heart of a long-standing conflict between the state’s forest department and its tribal forest-dwellers: the department sees them as encroachers while they claim traditional rights to till the land and gather its produce.

The three women are married into the same Nayak family whose homes are among the last before the dense forest begins. They had just finished their lunch of makai roti (corn bread), cabbage and chilli pickles when they sat down to tell their stories.

“Our ancestors have been here since the time of kings,” says Nandaben referring to the practice of veth, which allowed the royalty to seek voluntary labour from villagers in return for the right to live and work on forest lands. The free labour was used for construction, collecting forest produce, agriculture, tending to the royal retinue and animals.

Today, these families are allowed to live and farm on these lands as per the Forest Rights Act, 2006. But in our investigations across 16 villages in eight districts of the state, we heard many women complain about persistent harassment by forest officials despite official orders establishing their family’s land ownership.

Forest officials, however, have denied these allegations. Jaipal Singh, the state’s Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Land), maintained that officials intervene only when there is inadequate evidence to back an applicant’s land ownership claim or when the claims have been rejected.

“Even after eviction, a lot of people have tried to encroach on forest land. Even after regularisation [introduction of the FRA], encroachment has increased 3-4 times. When satellite imagery etc show that there was no cultivation on a piece of land and no occupation, they have to be evicted. Nothing can be done about that,” says Singh.

Forest rights

The Bhil Nayaks are a tribal community found mainly in eastern districts and their population is 4,270,351, or 47.89% of Gujarat’s total tribal population. Their livelihood options are limited due to poor education and lack of employment opportunities in these areas. Upto 89% of them are engaged in agriculture, cultivating maize, bajra, toor dal, rice and groundnuts.

According to a study by the Gujarat State Rural Road Development Agency (GSRRDA), only 50% of Bhils possess any land, while 39.4% are landless labourers, 2.2% are engaged in industry and the other 2.8% work as service labourers.

The Bhils have always claimed traditional ownership of lands but it was only in 1988 that the process of formalising these rights was incorporated in the National Forest Policy. The policy recognised the critical role of tribal groups in the protection and regeneration of forests.

The FRA, seeking to set right a historic injustice, acknowledged the “right to hold and live in the forest land under the individual or common occupation for habitation or for self-cultivation for livelihood by a member or members of a forest dwelling Scheduled Tribe or other traditional forest dwellers”.

So how can a claimant establish her or his ownership of a patch of forest land under the FRA? The law requires the Gram Sabha to collate documents supporting an individual’s claim and submit it to the Forest Rights Committee with 10-15 members appointed by the Gram Sabha, to verify the claims. The claim is then handed to the final claims authority — a government-appointed Sub-Divisional Level Committee (SDLC) of the state, consisting of officials of the forest department, block/tehsil-level panchayat and the Tribal Welfare/Tribal Affairs department.

Claimants need to submit three documents — evidence of Scheduled Tribe status, proof that “they primarily resided in forest or forest land for three generations (75 years) prior to December 12, 2005” and that they “depend on it for bonafide livelihood needs”. Those in the ‘Other traditional forest dwellers’ category require the latter two.

The titles are registered jointly in the name of both the spouses, or a single head of the household in case only one head is alive.

Struggle for recognition

Though the law now allows Nayaks to claim ownership, they often struggle with the process.

Nandaben alleged that forest officials begin harassing families the moment they apply. “They asked us on what basis we filed the claim. Do we have documentary evidence? After we said we did, they started beating up my brother-in-law claiming that the forest land belongs to the department. ‘Pack your bags and go to Kathiawar,’ they said. When we protested, they beat us up too,” she said.

The men from Dalit and Adivasi families in Dahod work at construction sites in the more prosperous Kathiawar region of Gujarat and return home for the sowing and harvest season. An FRA stamp on land ownership may not stem the seasonal migration for work in the area but it would give forest dwellers an alternative livelihood and legal protection against harassment by forest officials.

It is also not easy to lodge an official complaint against forest officials who harass the Nayaks, locals said. Their complaint at the neighbouring Rajgarh Police Station was rejected, they were accused of lying and chased away. The local civil hospital also refused to admit survivors because there was no police complaint to back their statements.

This was in 2011, when the family had appealed against the very first rejection of their application. A protest before the forest department and the police station followed after Anandi, a women rights organisation, took up the case. It was only then that the complaint was registered.

“You have come here without informing us, we will jail all of you on the charge of being ‘Naxals’, they told us, but we fought on,” recalls social worker Veenaben.

After five years, the Nayak family eventually won the claim to their ancestral land. “The harassment is now minimal. Sometimes when we go to the forest to collect wood, we are chased away but we atleast feel secure that no one will throw us from our own land. This is the land in which our ancestors have lived,” said Navliben Nayak.

Women bear the brunt

Women, often left behind to fend for themselves after the men of their family migrate, are easy targets for physical and mental abuse by government officials and neighbours and relatives who seek to usurp land, we found.

In Mahisagar district’s Charada village, Shantaben Manikal Makwana, 48, has been fighting a long battle with forest officials who will not let her farm on the forest land that she claims belongs to her family. A graduate from Gujarat University’s Santrampur campus, she is listed as the main applicant for 4 acres of land in the village that she and her family have been cultivating for years.

In 2007, soon after the Forest Rights Act was notified, she and her husband filed an application for the ownership of the land. The following year, however, he application was rejected. She followed the process of appeal to the District Level Committee but had received no information on the case until she approached the committee in 2013. Until then, Shantaben continued growing bajra and toor on the land, as allowed under law.

In 2015, though, two girls from her family had got into an argument with the then Forest Range Officer. The girls were watering the bajra crop when they were interrupted by a forest officer in mufti. The officer accused the girls of destroying the shrubs planted by the department. “She left first and then returned in her uniform, which was soiled and torn. The officer accused the girls of physically abusing her,” Shantaben alleged.

Amid the COVID19-induced lockdown in 2020, Shantaben alleged, forest officials brought in tractors to uproot the soil on which she had just planted seeds post-monsoon and built trenches to discourage her from farming.

“I lose Rs. 25,000-30,000 every year because of harassment,” said Shantaben. “I have a well in the land so I would’ve been able to farm really well and earn good money, but instead I have to bear huge losses”. Forest officials, she said, claim that they have no intimation that the land has been handed to her.

“Not having the legal right to this land and the constant intimidation affects us in many ways. We get no foodgrains, no money, and the education of our children suffer,” she said. “Our forest doesn’t even have enough produce which we can sell and earn money. We can only sell timru leaves during the season which fetches us only Rs. 2,000-3,000.”

Shantaben is the head of the village’s Forest Rights Committee. All the 29 claims from her village have been rejected and are under different stages of appeal. She believes that the community is harassed to dissuade it from persisting with the appeals.

“People here are not very educated nor do they understand the basics or benefits of having their legal title for their land. Sometimes they gang up against me with forest officials because they are scared and sometimes out of sheer ignorance,” Shantaben says.

Gender bias

Advocate Nilam Patel, who serves as Women and Land Rights Associate with NGO network Working Group of Women for Land Ownership (WGWLO) said there is gender bias in the manner in which land ownership is formalised in the area.

“While applications for claiming individual land are filed jointly by both spouses, the man remains the primary applicant in most cases. However, when the procedure is complete and the ownership is entered in the land records, the wife is left out,” she explained. “Because of this, women are unable to avail government benefits and farm schemes such as Kisaan Samman Nidhi Yojna, low interest loans, etc.”

If the male claimant dies, the widow then has to go through the whole process of claiming ownership all over again, said Patel. An instance of this bias was reported in Dahod district, in the case of Chanchiben Shankarbhai Kodi taken on by the WGWLO.

Chanchiben’s husband had claimed rights to 2 acres of land at Sagatara village for the family in 2008 but did not live long enough to be granted its ownership. After his death in 2019, Chanchben took charge of the 24-member family. She alleged that during one of the inspections, a neighbour bribed an official to scuttle Chanchiben’s land claim. “I just want the land for my family, nothing else,” Chanchiben said. “We are a large family and this land provides us food and shelter, as well as ensures a secure future for my children and grandchildren.”

The Gujarat scenario

The Gujarat government has been pulled up by the courts for its track record on granting forest rights: In November 2020, the Gujarat high court told the government it was not doing enough to protect the interest of tribals and other forest dwellers in the conversion of forest to revenue land.

As per data collated by WGWLO, of the 4.2 million total individual claims received nationally upto December 2020 under individual forest rights, the approval rate was 46%. Further, 1.7 million claims were rejected, while decisions on 500,000 claims were pending.

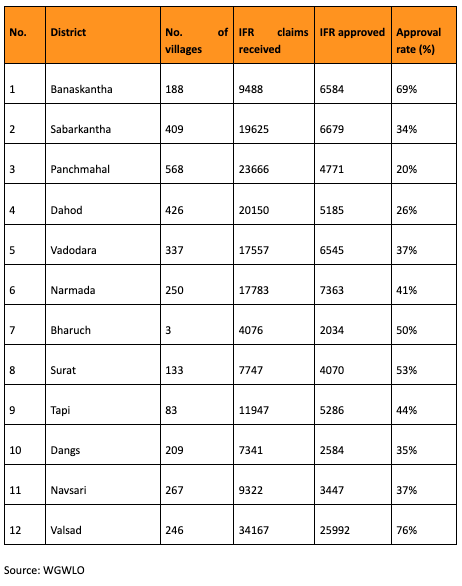

District-wise breakup of IFR claims approved in Gujarat

Approval rates are high (50-70%) in states such Tripura, Telangana, Rajasthan, Odisha, Kerala, Jharkhand and Gujarat. Odisha has the highest number of approved claims at 70%. West Bengal, Uttarakhand, UP, MP, Karnataka, Bihar and Chhattisgarh have high rejection rates (50-98%); Bihar and Uttarakhand top the list (98%).

WGWLO found that despite a 50% approval rate, the area approved in Gujarat in many cases was low compared to what was claimed. Besides, the state government had initiated the survey and mapping of only the lands approved by the District-Level Committee – almost 50% of the total. GPS mapping is recognised as the most effective evidence for granting approval.

“It is also to be noted that the Gujarat government has not updated the claims data since the year 2016, and that they have stopped processing new claims. The work on the old claims is been undergoing at the snail’s pace, however new claims are accepted at Gramsabha/FRC level or maximum to SDLC level,” WGWLO said in the report.

Districts with high populations of ‘other traditional forest dwellers’ (OTFD) communities such as Sabarkantha, Panchmahal, and Dahod have low approval rates. Most claims made by pastoralist and OTDF groups have been rejected for not having sufficient proof of residence for 75 years.

Handful of empowered women

Although joint applications are common, as required by the forest rights law, only a handful of married women are registered as main applicants. In the 8 districts visited for this investigation, there were only three. Apart from Shantaben, Phuliben Rumelabhai Pagi from Mahisagar district, Kesiben Andharbhai Nayak from Dahod, and Sumitraben Tejanand Gamit from Tapi district were listed as main applicants.

Phuliben, 45, and a mother of two, had first claimed her right to land ownership even before her husband, a rare instance. Even though she will only sit on the ground with her head covered in the presence of men, she mustered enough courage to tell her husband that she deserves to have a piece of land in her name. “I told him (her husband Rumelabhai) when I till the land and take care of the farm, why should it not be in my name,” she says. “Luckily, he agreed. I feel a sense of empowerment that I own something that is just mine. I can make decisions like what to sow, how to use it or what to do with the harvest.”

Kesiben, a widow, says that having her land claim approved has brought her respect. She has acquired decision making rights on how to run the farm that grows maize and jowar. “At least now I don’t have to worry about who will usurp my land so I can focus on increasing the quality of my crops and sell them at a good price,” Kesiben says.

A study by WGWLO, ‘Implementation of Forest Rights Act (FRA) – Ensuring Women’s Forest Rights’ noted that although women are recognised as legal heirs in their maternal family, in practice they are not considered worthy of inheritance. If widowed, they end up becoming dependents.

“Firstly, widows cannot claim rights over the forest land that they possess (that was jointly held with their husbands) since rights over the same parcel of land are claimed by (and in many cases vested in) relatives of her deceased husband such as an uncle or a brother,” it said. “Similarly, single women are also thus disentitled owing to the fact that land under their possession is claimed by one of her male relatives, most often her brother.

“Additionally, where rights have been recognised, the records formulated do not bifurcate land holdings. That is, several rights-holders have their names registered on the same parcel of land. Women are strongly discouraged to file claims and where they do file claims, conflicts arise as the two claims over the land compete for legitimacy. The statutory mandate to record the names of both spouses in the Record of Rights over forest land has largely been followed in practice, but, this distinct facet of the disentitlement of women from land that they own and possess, remains unaddressed.”

‘Only educated women think of such things’

In the case of Sumitraben, her husband chose to recuse himself from scrutinising his own claim to land because he is the head of the Forest Rights Committee of the Noorabad village in Tapi district. Instead, he made his wife the main applicant. Although Sumitraben is also a member of the FRC, her knowledge of the law is limited. “Among us tribals here, women take charge of finances so in a way we are incharge. It doesn’t matter whose name the land is in,” she says.

When I asked if she received any land from her paternal family, I was interrupted by a man who said asking for land from the father’s family is not right because the brother’s claim is paramount. “It is a very urban idea to ask for land. It disrupts family relationships and is unnecessary. Only educated women think of such things”.

Education of women, as an Asian Development Bank report found out, was an important factor in enabling them to participate in decisions about nonfarm activities, household expenditure, and farming. Providing women with more education and giving them access to on- and off-farm employment opportunities could increase their status in the family in terms of decision-making, it noted.

“Women’s land title ownership enhances their status and decision-making power in the household. However, the impact of women’s land title ownership on women’s participation in family decision-makings… can be influenced by the awareness of the people about the legal provisions for inheritance and the implementation of inheritance rights,” said the the study titled ‘Women’s Land Title Ownership and Empowerment: Evidence from India’.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.