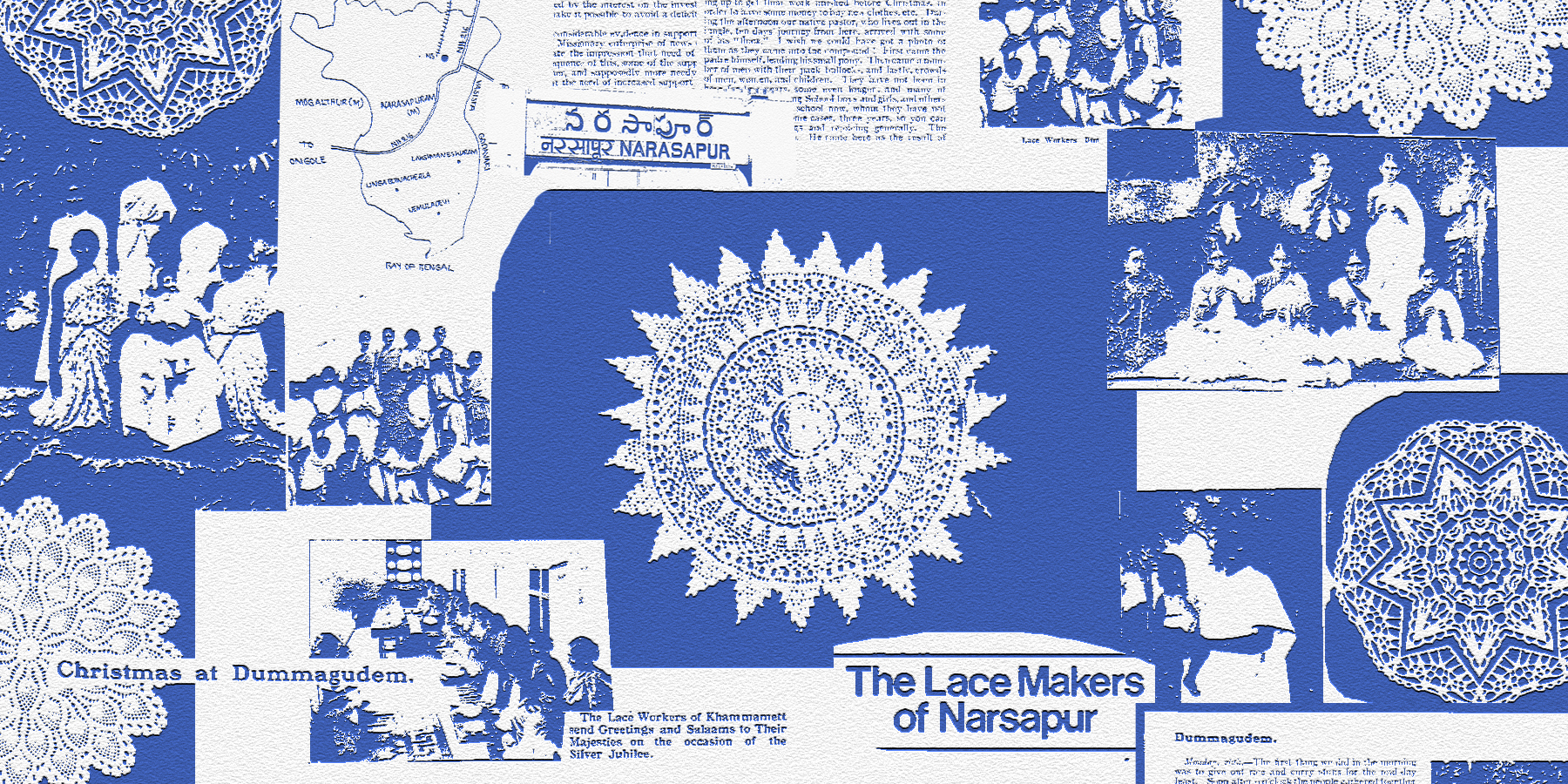

Dalit Lacemakers Of Narsapuram: How They Found Dignity And Livelihood In 19th Century

A craft brought by the missionaries changed the lives of Dalit women in multiple ways before it became the domain of a dominant caste

- Sri Harsha Sai Matta

It took me a 20-minute ride on my babai’s (paternal uncle) Scooty to get to Serepalem village, 4 km from Narsapuram, a small town in the West Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh. I was accompanied by two men who work as agents in the area’s renowned lace-making industry.

In the living room of one lacemaker, four or five women sit on a large mat working with their crochets. I ask Anasuyamma, the oldest among them, about her earliest memories of lacemaking. “Long ago, women would come from Narsapuram bringing pekalu (balls of thread). Later, in our time, men started bringing this thread and giving us designs and patterns as the order demanded,” Anasuyamma recalls.

Peddinttlamma was 15 when she was handed lace thread and crochet, a year before she got married. She has been making lace for 40 years now. “We went to school but it was not in us to get educated,” she says .

These stories mirror the experiences of most women gathered in the hall. They all belong to the dominant, landowning caste called Kapu community, where strict rules of patriarchy demand that women can only seek home based employment. Some of the women are in their 50s, others young and newly married. Once their husbands leave for work and the children are packed off to school, they sit and make lace together as they chat.

“We are idle once everyone else leaves and it is boring. Lace work allows us some leisure, some work,” says Peddintlamma. “But the work is not painless,” interjects Anasuyamma. “After holding the thread and the needle for two hours our eyes start aching. But we continue doing it because at this age resting all day might make us fall ill quickly.”

For Peddintalamma lace making has become a habit she finds hard to drop despite age and weakened eyesight and hand strength.

But there was a time, about a century ago, when the craft of lace making in Narsapuram was the preserve of Dalit women. When and how did this change? To understand this , it is important for us to go back in time.

Lace Making Arrives With Missionaries

Emerging from the courtly traditions of Early Modern Europe around the 16th century, the art and craft of hand-made lace made its way to India through the missionaries who arrived here from the British Atlantic World in the 19th century. Lacemaking involves the crafting of varied, delicate patterns using a needle and thread to embellish apparel.

Lace is often made using casual female labour. It is expensive so its makers cannot afford it or the clothes it decorates. But how did it reach Narsapuram?

Narsapuram has long been an ancient port and a trading centre on the Coromandel Coast. The Godavari river enters the Bay of Bengal here and this facilitated trade for the Arabs, the Dutch and the English. The missionaries later entered Narsapuram the way merchants did. Hence the history of Narsapuram town is deeply intertwined with the history of Christianity in the region.

Sociologist Maria Mies in her book, The Lace Makers of Narsapur, traced the origins of the trade in the city to the arrival of missionaries like George Beer and William Bowden. They set up the Godavari Delta mission in 1837 and later two more missionaries from Scotland, one Mr and Mrs Macrae, joined them. Local history has it that these were the pioneers of lace work in the region.

In 1876-8, the Great Famine struck the districts of Madras Presidency due to failed monsoons, resulting in severe drought and crop failure. Mies writes that lace making became a means, especially during famine years, by which missionaries aided the poor, especially Dalit converts from Mala and Madiga communities. The women of these communities traditionally worked as agricultural labourers and also took on other kinds of manual tasks during famine such as brick-making, digging canals, and so on. It was in these years that, encouraged by the missionaries, these women chanced on a new livelihood, lace making.

Missionaries supplied them the thread and taught them lace patterns. Soon, lace making acquired a regular production pipeline, the finished goods were exported by these missionaries to their friends and dignitaries across the British Empire.

From Mission To Industry

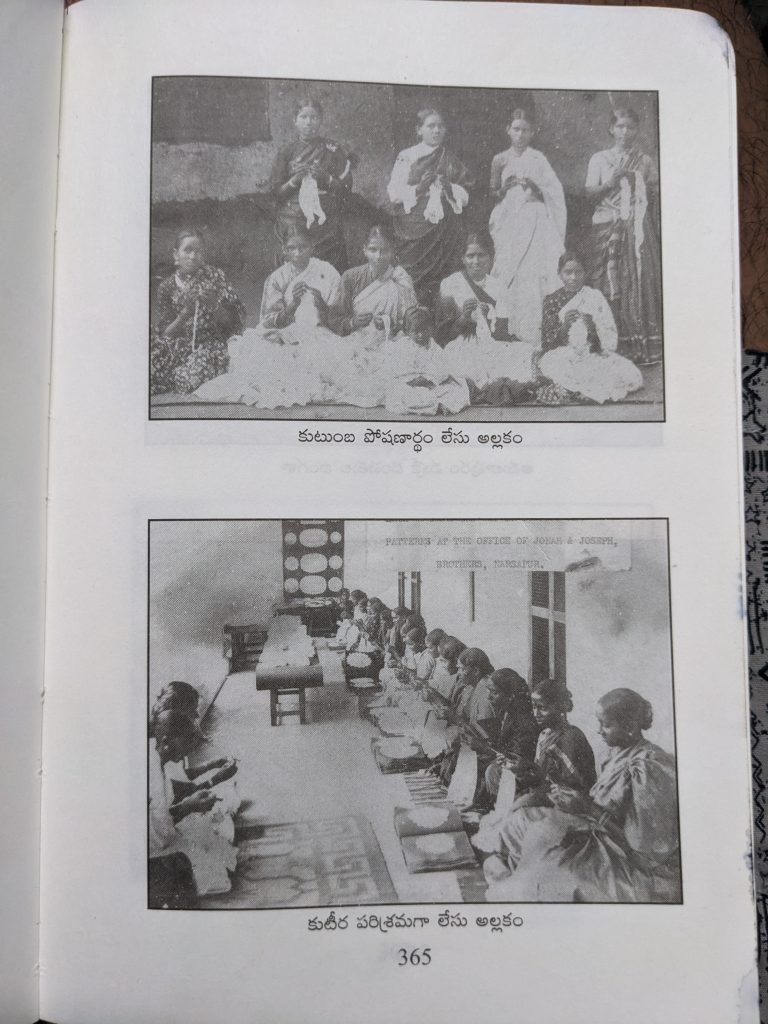

In 1900, two teachers from the community of Dalit converts, Chadalavada Jonah and Chadalavada Joseph, took over the lace business from the missionaries. By now, Mies writes, the nature of the lace industry changed. What was once a missionary means to support and sustain Dalit women, under Jonah and Joseph, became an industry and lace making was opened to women from other communities as well, such as the Agnikulakshatriyas, a fishing community.

Eventually women from the Kapu community began to make lace at home. Within the next few decades, the industry itself was taken over by the men from the Kapu community. The Mies book traces this transformation but I was curious to understand a few other things. Did the early Dalit lace workers entirely leave caste-ordained work like agricultural labour, leather work and so on? Or did they do both?

In her book, Mies says that organisational and ideological changes took place in the lives of the Dalit women who had become lace workers and Christian housewives. These changes must have brought many shifts in their lives. To find answers to these questions I immediately left for my village in Narsapuram to try and interview elders in Mala-Madiga hamlets and perhaps find narratives about early Dalit Christian lacemakers.

The Caste Shift

I began with my father. Did he know that Dalit women were the first to make lace in Narsapuram? He was surprised to hear this. “I never knew this. Laces were popular in the region and most women in the village were making it, irrespective of their caste. Even in our Churchpeta (a hamlet inhabited by the Mala community) some women used to make lace. A boy of your age used to come on a cycle and give [lace] threads to the women. Pregnant women were the most eager to make lace – they could listen to songs on Vividh Bharati sitting on a rocking chair or bed as they made lace,” he recalls.

I then set out to meet the family of Jonah and Joseph. Their grandchildren were likely to be in their late 70s now.

I met one of them – Dayaswaroop Jonah – and asked if there were any lace workers from (Dalit) communities in his grandfathers’ time. “I always thought it was the men from our communities who managed this business and the women [lacemakers] were from different castes. For example women in the fishing community used to sell fish early in the morning and then make lace during the day. So, there must have been women from (Dalit) communities who made lace but I only remember that men from Christianpeta [a hamlet inhabited by the Madiga community] sold the lace.”

I met another grandchild of the brothers, Kalyani Thomas, a doctor who runs the mission hospital set up almost a century ago. What were her memories of lacemakers? “What remained striking to me was that everyday there used to be a lot of pregnant women at the hospital. Many women in my time used to make lace on the hospital bed as somebody would give them some thread and needle. It seems that much earlier missionaries would hand this material to women patients in the hospital and they would instantly start working on the lace while the missionaries would preach,” she says. Another elder at the hamlet told me that women converts would sit in the ground next to the church and make lace as they heard the pastor preach and this tradition continued till his time.

A lace exporter from the Kapu community, who is also a Christian, had more information to share: “Lace is like the food God gave in the times of famine, just like the five loaves and two fish in the Bible. This lacemaking was first taught to all the women in the village, not just Christian women. But the poor Christian women’s need to survive has turned them towards lace making [for livelihood]. Later, these women went to schools, educated themselves and got jobs. None of them today toil in the field or make lace. Now only Kapu women make it because they don’t go to school or do field labour.”

However, I was still obsessed with the idea of finding some direct information about early Dalit lacemakers. How could I do this? Then I found a way: Let us go back in time again.

Other Lace Stories From Godavari

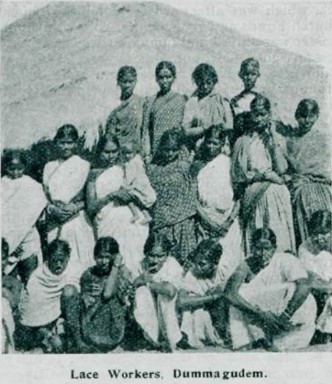

In the Madras District Gazetteers of Godavari, 1915, it is noted that lace making was taught to the women of Dummagudem so they could earn a livelihood during the famine of 1896-7.

“Will the readers come in imagination and spend a day with us at Dummagudem?” writes a missionary in 1918, whose letter is published in a magazine called “India’s Women and China’s Daughters” published by the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society. Letters like these are written by missionaries to the White Christian readership across Britain and its settler colonies to solicit donations for their evangelical work.

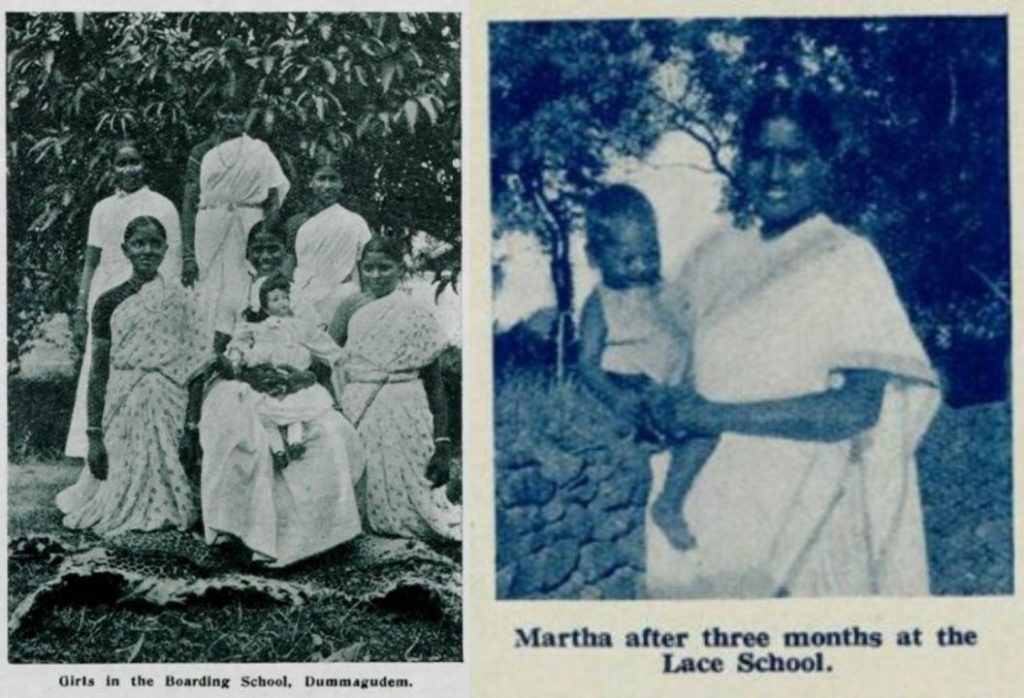

The missionary in this particular letter writes about setting up a boarding school for Women in Dummagudem, where they are taught lessons in Bible and lace work. “Most of our children come from Christian homes, but we also take in Non-Christians. With a few exceptions our children belong to the Panchamas or the so-called depressed classes,” she says.

In 1911, the same missionary wrote: “For some time now my time has been very much taken up with our Industrial work, which, I am thankful to say, continues to flourish. It has been the means of bringing some of the Lace Workers into the Fold of Christ.” In 1912 she lists the wages of a coolie woman from the outcaste community at 2-3 annas and reports that a good lace worker can earn as much as 10-12 annas! In 1905, she talked about the importance of cleanliness in lacemakers and the need to make them “civilised”.

.“The village Christian women of the Khammamet district are bitterly poor, for 99 percent of them belong to the field labourer section of the Outcastes,” writes another missionary in 1925, from Khammamet. She too talks about how the lace enterprise began as a famine relief and to initiate Christian faith into the labouring women. The wages allowed the women to cope with the lean season in agriculture, when famine reduced the demand for labour work. The notes of these missionaries, at both Dummagudem and Khammam, point to an interesting fact – apart from their earnings, lacemakers in the region were proud about the changes their new trade brought in their personal appearance. They were now considered “clean” and given pure white clothes by the missionaries.

The two regions, Khammam and Dummagudem are nearly 300 km from Narsapuram, but are connected by the Godavari river. This is what links their lace stories.

Quest For ‘Purity’, Dignity

Scholars like Jane Haggis writing on marginalised caste groups and Christianity in South India point out that motives and ideology of the missionaries were not very different from the colonising/civilising endeavour of the British in regulating and defining the ideals of femininity and womanhood.

Missionaries established the basic shape of ‘Women’s Work’ where work in the household or in closed shelter was seen as more appropriate than manual agricultural labour or other kinds of public work. They inculcated habits of neatness, cleanness and industry among Dalit women through lace work and thus, schooled them in Christian virtues of morality and class. But it is also important for us to understand why Dalit women sought these virtues.

Eliza F. Kent points out that these notions of Christian modesty imbibed by converts were also a path for the communities to attain respectability. Recall the sartorial revolts of the Nadar women from Travancore region asserting their right to clothe themselves like Nair women and how this enraged the caste ego of the Nairs. In the larger Brahminical superstructure that decided on the pure and impure, and where Dalits were stigmatised into doing degrading tasks, Dalit women converts taking pride in their white clothes and making “clean” lace was a route to finding purity and dignity in work. So, apart from fighting famine and hardships through increases in wage and food, what becomes wholly important is the kind of social quest Dalit women sought, through lace making and the change to the Christian way of life.

Work From Home

Today, lacemakers earn barely Rs. 50-100 a day. What if they decide to handle the business themselves, buy the raw material and sell the product? “These women don’t want to come out of their homes [to work]. They are better off making lace at home,” said one of the men I met to talk about the contemporary lace industry. He is an agent who earns nearly Rs 20,000 for delivering patterns to the lacemakers and initiating them into work.

“We definitely want a wage increase. But like he said, we are Kapu women. Our husbands won’t agree to us going out. We ourselves shame other women who do field work or sell things outside,” said Shakuntala, another lacemaker.

In her book, Maria Mies talked about the gosha (purdah) values within the Kapu community that enables men to keep women confined at home, doing lace work at low wages. But it is also important to note how deeply entrenched caste values shape the identity and mobility of these women and enable the capitalist accumulation of Kapu men and their control over the industry.

Why are Dalit women not making lace anymore? “Where is the need? All of them are nicely getting educated, becoming doctors, teachers and so on,” counters Sudheer babai.

In 1893, the Madras Presidency, encouraged by petitions from the missionaries, made proposals for the education of the Panchamas. The 1854 Wood’s Despatch, one of the earliest documents that provoked the spread of education in India, resulted in increased stress on women’s education and this affected the initiation of Dalit women into vocational education and this included lace making. Dalit women also became Bible women and took to preaching to the women in zenanas and upper caste households.

All these different skill sets and learning experiences eventually transformed the way Dalit women received education. The history of lace making in Narsapuram told me a familiar yet alternate story of how social change and mobility varied for women across the social hierarchy in terms of how they negotiated with caste, patriarchy and religious value systems. This Dalit History month, remember every Dalit in your life and every community’s indefinite struggle against caste — in this case, the Dalit Christian women who crafted lace, and their lives.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.