Dalit Women Wait To Till Their Lands In Gujarat

- Meenakshi Kapoor

“We were happy — we wouldn’t have to work in others’ fields anymore. We were going to be farmers,” says Daksha Ben Babu Bhai Parmar, a Dalit farmer, recalling how her family had rejoiced at being allotted a 3-acre plot by the Gujarat government in 2006 under the Zameen Santhani scheme. The land scheme was meant to benefit those like her– marginalised, landless farmers who work for a pittance. She and her husband Babu Bhai live in Malvan, a village in Surendranagar district

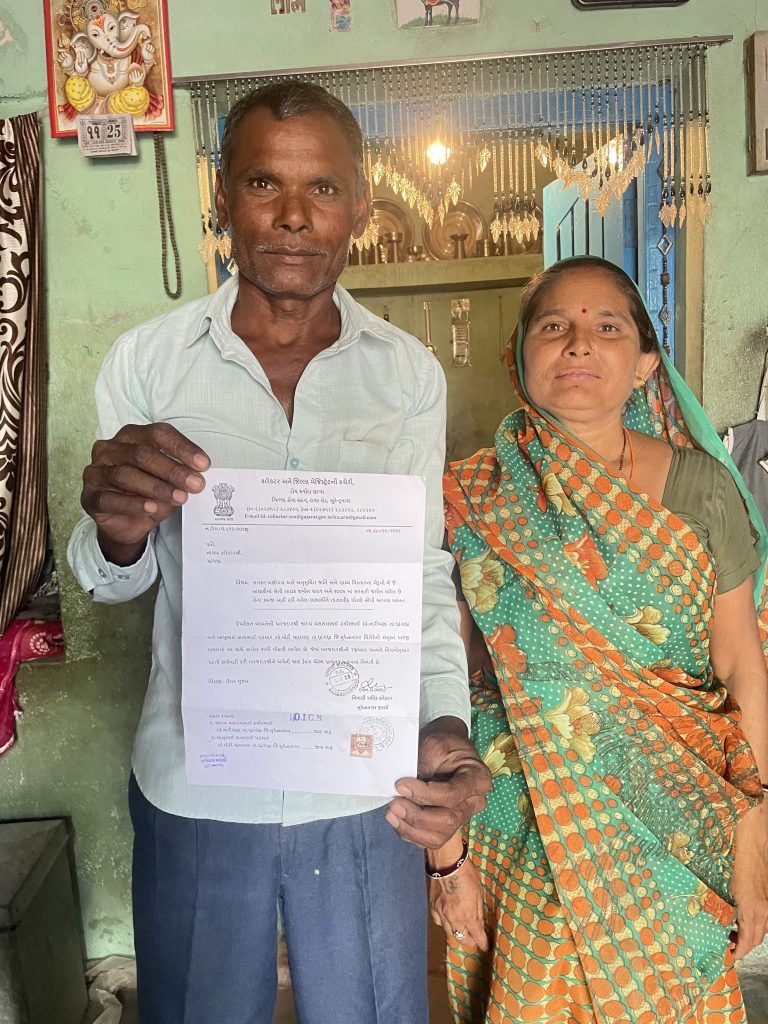

The Parmar family’s celebrations in 2006 were short-lived — the allotted land was 10 km away, in the Little Rann of Kutch, where the soil is saline and uncultivable. “I will not be able to grow anything there,” says Daksha Ben, holding up the land documents she got 15 years ago as sanyukta khata (joint ownership) with her husband.

The Parmars did not accept the land that they had waited for all their lives. 64 of the 84 Dalit beneficiaries in Malvan who received land under the Zameen Santhani scheme, could not grow anything on it.

Land is allocated to Dalits, Maldhari, other scheduled tribes and castes under the Gujarat Agricultural Land Ceiling Act of 1960. The Act sets a limit of 54 acres per individual owner, though there are some regional variations on this. Surplus lands are acquired from large landholders by the government and then redistributed among the landless. Besides the surplus land, under the Zameen Santhani scheme, also initiated in the 1960s, district authorities identify wasteland, acquire it, advertise for applicants and then distribute it to the eligible — landless agricultural labourers, marginal farmers, ex-servicemen and registered cooperative societies of backward classes.

Between 2005 and 2009, administrations of 19 districts allotted almost 20,000 acres of wasteland to nearly 7000 landless families under the Santhani scheme.

However, most of the land allocated under the Santhani scheme was uncultivable, says Mudita Vidrohi, member of Gujarat Lok Samiti, an Ahmedabad-based voluntary organisation that has helped land grantees make their land usable

We investigated the failure of the land distribution scheme in empowering Dalit farmers in two districts of Saurashtra– Surendranagar and Bhavnagar. Over a quarter of the Dalits in the state live in Saurashtra. Scheduled castes make up 11% of Surendranagar’s population, the second highest in the state. The two districts together have over 24% of the wasteland in the state.

Slow redistribution of land

Landless agricultural labour is the ‘largest segment’ of Indian society. Of the 263 million persons engaged in farming activities, 144 million are landless workers, according to the 2011 census. Landlessness has remained high in India despite land reforms and has been on the rise. In the decade between 2001 and 2011, the number of landless agricultural labourers rose from 106.7 million to 144 million, an increase of 38%.

Landlessness is closely associated with caste in India. Almost 70% of Dalit farmers are agricultural labourers working on lands that do not belong to them, the 2011 census data showed. Dalits own only 9% of the total agricultural land in the country, according to the agriculture census of 2015-16.

The results of the redistribution of land resources in Gujarat did not have any significant impact in correcting the caste imbalance because the pace of implementation was slow — 60% of its Dalits remain landless labourers, according to the 70th round of India Land and Livestock Holding Survey conducted in 2013.

We spoke with three Dalit women farmers, all from the Vankar (weavers) community who received land from the Gujarat government years ago. Two of them are from Surendranagar district and one from Bhavnagar. None of them have been able to use their plots, which are either unavailable for various reasons or are unsuitable for farming, or both.

In Malvan, the land was too saline; in Rajgadh, it was full of boulders and belonged previously to the Forest Department; and in Kareda village in Bhavnagar, a portion of cultivable patches between the rocky and saline land was encroached by dominant caste families.

Our investigation showed that the women farmers have struggled with red tape, discrimination and the backlash from dominant castes to cultivate what they can, to make some sense of their ownership of these barren lands.

‘I own a hillock’

In Rajgadh village, 18 km from Malvan, on a hot March afternoon, Lakshmi Ben Mohan Bhai Parmar took us to the land allotted to her. The 8-km auto rickshaw ride to the field runs through a pagdandi (dirt track). Normally, Lakshmi Ben walks this distance.

The land is full of big boulders and even has a small hillock. “Yeh pahad mera hai (this hill is mine),” she says with a smile that is a painful grimace. Lakshmi Ben received land under the Santhani scheme in 2006. “Of the 100 [applicants], only eight were cleared, and six of us were selected,” she says.

Lakshmi Ben and four other women from the Dalit community and one from other backward classes (OBC) received 3 acres each in 2006 in Jegarwa village of Dhrangadhra block. They later found out that the land belonged to the Forest Department. “We were told if we used our lands we would be imprisoned,” Lakshmi Ben recalls.

The order of land allotment came in 2006 but for 10 years the department did not allow the land to be used.

Between 2006 and 2017, the six Dalit grantees from Malvan, with help from NGOs, repeatedly applied to the then district collector and mamlatdar, who heads the revenue administration at the block level , for rights to cultivate their land. They only got verbal assurances. In 2017, the women complained to a block level officer. They requested that the forest department map its land, exclude this from the allotments and allow them to farm on the rest.

“In the same year, I got to meet with the district collector when I accompanied other women to invite him for an NGO meeting. He listened to my problem and promised to help. Within months, I got the land. God bless him,” says Lakshmi Ben. “After 12 years, I got a piece of land that did not belong to the Forest Department or anyone else.” She and other women received a government order in 2018 that they would be allotted fresh land.

Lakshmi Ben and five other women received two acres (~5 bigha) each, within Rajgadh village. But most of the land is rocky. Only two women in the group can till their land but only about one-fifth of it. “We own land but we still have to work in fields owned by others — Rs 100 for half a day of work” says Lakshmi Ben.

Solutions exist, only on paper

A 2019 study, ‘Land Reforms and Dalits in Gujarat’ by Manjula Laxman surveyed 423 individuals across 27 villages in six districts (Ahmedabad, Banas kantha, Bhavnagar, Surendranagar, Amreli and Kutch) and found that 73% of the land allotted under the state’s land ceiling Act was unfit for direct cultivation because it was “saline, waterlogged, uneven or stony”. Her research reveals that only 4% of the respondents of her survey had received “somewhat irrigated” land.

The state government provides some financial assistance to the allottees to make the land cultivable but it is too little, notes Laxman, pushing farmers to invest a significant amount of labour for just subsistence farming. We find that even this financial help is hard to get.

Lakshmi Ben and other women farmers went to the district office of the agriculture department with a scheme document from 2018-19. Under the scheme, Santhani allottees could be given Rs 30,000 per hectare (~2.5 acres) to clear it for use. But the group returned disappointed.

“We went to the Surendranagar Kheti Badi Vibhag (agriculture department) and showed them the scheme order. They said they didn’t know about it. They asked us to leave a copy of the order with them. But we didn’t hear back,” says Rita Jhala, who, till March 2021, worked as a paralegal with the Working Group for Women and Land Ownership (WGWLO) Network, a Gujarat-based network focussed on women’s land rights.

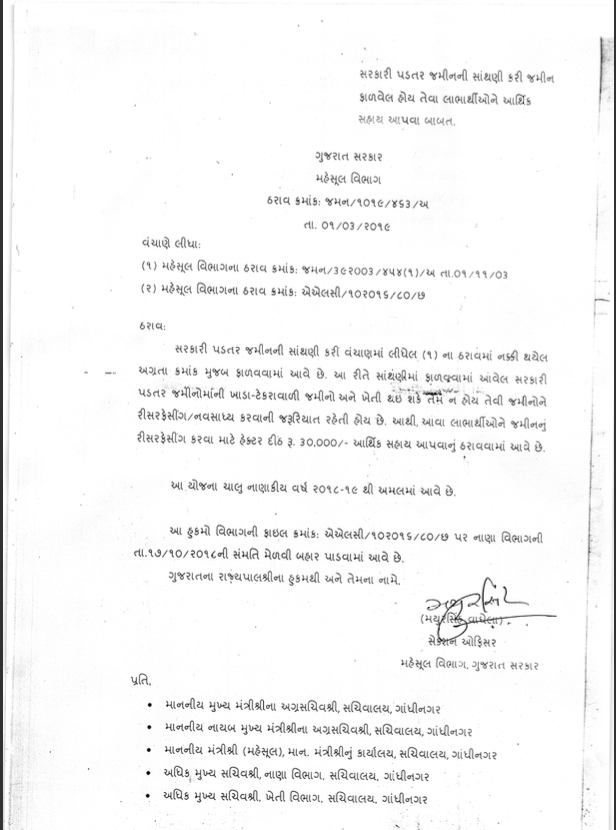

2018-19 Scheme provides support to Santhani allottees to prepare their land for cultivation

“Given the geography of the district, here often it is seen that the land allotted to landless is rocky or saline. This land could be made cultivable under MNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Act) 2005. But it is not the priority for the authorities,” says Jignesh Mevani, a Dalit activist, lawyer and a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) from Vadgam. “The bigger issue is the actual possession of land.”

We found such a case in Bhavnagar.

‘Our parents feared for our safety’

The walls of 67-year-old Mangi Ben Baya Bhai Gilatar’s house in Kareda village of Ghogha block in Bhavnagar are decorated with framed photos of jurist-reformer BR Ambedkar and the Buddha. She has 10 bighas of land in her husband’s name and two buffalos and a calf in the cattle shed across her home. “I pay mehsul (tax) for the entire 10 bighas,” says her husband Baya Bhai Gilatar.

Mangi Ben grows jowar, bajra and vegetables on her land but only for the family’s consumption. This is surprising because Bhavnagar is one of the most fertile districts of Gujarat: cash crops such as cotton, groundnut, onions and fruits are major contributors to its economy. Ghogha, particularly, is dominated by horticulture.

“[Of the 10] I can cultivate only 3 bighas,” Mangi Ben says, explaining why she does not sell her yield. Baya Bhai had been given 10 bighas under the Santhani scheme around 30 years ago but he only has possession of six because dominant castes have encroached upon the rest. Of the 6 bighas with the family, only three are cultivable because the rest partially is on a dholav (small hill). “Dholav ki chadhai par piyat nahi kar sakte (We can’t irrigate a slope),” points out Magi Ben. “Acchi fasal nahi hoti is zameen par. Rabi mein toh kuch nahi hota (Good crops don’t survive on this land. In winter nothing grows here).”

By August 2021, the family had levelled the slope but the land remains highly saline, says Ashokbhai, Mangi Ben’s 30-year-old son, the youngest among five siblings.

Four bighas owned by the Gilatar family continue to be occupied by dominant caste families from the neighbourhood. Reclaiming it could pose a risk to the family’s life.

“Hum chhote the toh papa mummy hamare liye darte the. Woh paise wale log hain, unki dadagiri chalti hai. Par hum ab iss saal apni zameen chhudwane ke liye procedure karenge (When we were young, our parents would worry for our safety because these are wealthy and influential people. But this year we will start the process of getting our land released),” says Ashokbhai, who is also an advocate, a Dalit activist and a member of Mevani’s Rashtriya Dalit Adhikar Manch.

Mangi Ben’s fears for her family are not unfounded. On July 24, 2021, Balwant Rathod, a Dalit farmer from Vav village in Banaskantha, was allegedly beaten up by seven men of dominant castes. The Rathod family had got the land from the government in the 1980s but did not have its possession till two years ago because it was illegally occupied by dominant caste families. He managed to repossess the land in 2019 but he has been threatened and his crops have been destroyed several times, alleges Mevani.

“Since most land is acquired from the big landlords, over 80% of the cases of land allotments in Gujarat are of pending physical possession of land,” says Mevani.

Fighting for possession

The state allegedly has been unable to give physical possession of the land allotted to Dalits because of political and bureaucratic reasons. Laxman too found in her 2019 study that for most allottees “a normal course of law enforcement” did not ensure the possession of land. Dalits had to collectivise and assert their rights, take legal recourse or assistance from social activists/organisations to get physical possession of their land, she added.

In 2012, the state had claimed to the Gujarat High Court that it had allotted 1.6 lakh acres of surplus land under the Land Ceiling Act to over 37,000 landless people. But two years later, a Right To Information application filed by Mevani showed that only under 17,000 Dalits have actual possession of the land. “The rest was only on paper,” he says.

Laxman notes in her paper that according to Gujarat Land Reforms Commissioner Office, as of 2016, 23,595 landless people were allotted a total of 1,21,094 acres of land in the state. Of these 15,705 were from the scheduled caste.

Under the Court’s direction the state formed a committee to identify cases where grantees had not got the land allotted to them. It was supposed to provide periodic action taken reports. So far, it has submitted only one, four years ago, alleges Mevani. It revealed that land measurement and allotment were pending in many cases and that there had been encroachment by dominant castes. The state has pleaded that since the task is “huge”, the case should be disposed of, says Mevani.

In Malvan, Babu Bhai is adamant he will not accompany us to the land allotted to the family because he does not want to “travel that far”. He is also weary of the 15-year struggle that he — and his fellow farmers — have endured. “We have made several rounds to the offices of mamlatdar. We even went to Gandhinagar once,” he says.

In February 2021, the families sat on a daylong satyagrah at the mamlatdar’s office. “He heard us and promised us that we would get the land,” Babu Bhai recalls. But a month later, the official said on a visit to Malvan that the families would only get Rann land. The farmers agreed to this. “We will grow what we can, pay the vighoti (tax),” says Babu Bhai

‘My parents didn’t know they had land, govt took it back’

If the farmers turn down the Rann plots, or do not pay the tax, the land goes back to ‘Shri Sarkar’ (as government ownership is referred to). On field visits, we encountered several such instances.

Kanak Vankar of Sadla village in Surendranagar’s Patdi block has one such story: “My grandparents, who were salt workers, got 18 bighas of land from the government in 1972. But for many years they didn’t know about it. They continued labouring at the Rann saltworks. In 1988, my parents found that they had land in their family name and started tilling it and paying tax on it. But then we found that the land was back in Shri Sarkar’s name. We have been applying to various government offices to reclaim it. The collector agreed that the land belonged to us but we haven’t got it back.”

WGWLO too has identified a case where a family from Tharipar village in Dhrangadhra block is trying to reclaim its land lost to the government. In Rajpur village of Dholera block of Ahmedabad, 50% of the land given to the Dalits and other backward castes is back with Shri Sarkar now, say locals. “On the pretext that the land is lying unused, it is then handed to industries,” says Mevani

The state government has made several attempts in the past to hand over wastelands/ agricultural lands to industries and corporates for contract farming claiming that the land was lying unclaimed and unused. The claim has been challenged by Dalit groups in the state.

“During 1982-89 the implementation of the Agricultural Land Ceiling Act was done intensively in Gujarat and all over the country. But thereafter a change came in the approach of the state government. The government records show that land redistribution process is almost complete, but actually it is done like half glass of the water,” says Laxman

We spoke with the mamlatdar and the naib tehsildar (additional deputy commissioner) of Patdi block in Surendranagar about such cases. “If it is a new tenure land, and the conditions are not followed i.e. the land is not being used for agricultural purposes, it can be taken back. If the terms of the law are violated for over three years, the land comes under government control. Land should not be sold. If any of these conditions are violated the land goes back. The person can be forgiven once but not after that,” says Jadav Kalidas, the naib tehsildar of Patdi till July 2021.

To reclaim the land, an application has to be sent to the naib tehsildar who decides the case. But if the applicant is not satisfied with the verdict, it can be appealed under section 211 and 203 of the Revenue Act. The case then goes to the collector, according to Kalidas.

Between their battles with government apathy, red tape, the hostility of dominant communities, and fear of losing the land to the state, Dalit farmers continue to struggle for livelihood even as large tracts of land allotted to them lie unused or under others’ possession.

This reportage is part of the WGWLO and BehanBox fellowship on women’s land, forest and farming rights in Gujarat

This story is edited by Malini Nair

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.