Beyond The Courts: Taunts, Trauma and the Weight of Waiting for this Irular Family

The jobs they were denied, the insults they learned to ignore, the fear that their children learned and resisted – an Irula family is still dealing with the aftermath of a terrible injustice

- Smitha TK

Trigger Warning: This article contains mentions of sexual violence. We advise reader discretion.

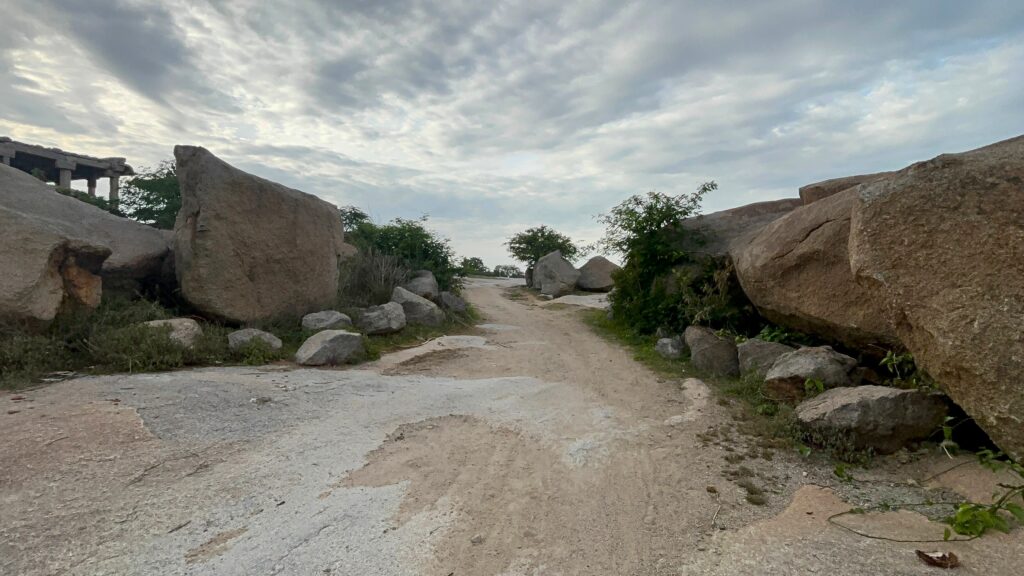

“We are like a family of sparrows. Always together. They tried to break our nest, pluck out the sticks, and scatter us. But we’re still here, holding on to whatever little we have left.” Raji* sat perched on a rock as she spoke of her family’s trauma and resilience in the face of a sustained campaign of violence and vilification over the last 14 years.

The dying sun traced every line on her face, etched by years of worry and work. One by one, the other family members joined her. That evening, her family prepared a simple curry using the meat and beets they had gathered.

What Raji was referring to had long stopped being a headline but everyone sitting there carried the story in their bodies, their silences, and routines. We had in the first part of this series recounted the story of the alleged sexual assault on four Irular women in November 2011 by police personnel in Villupuram in Tamil Nadu and the brutality their families had to suffer in custody.

In this, the second part of the two-part series we move away from chargesheets and courtrooms to examine what lingers after the violence, especially for women and children of the family: the jobs they were denied, the taunts they learned to ignore, the paths they were told not to walk, and the fear their children learned before they learned to read.

Over the past 14 years, that horrific night has travelled with them into workplaces, into schools, into marriages, into how they are looked at and how they look back. Lawyer and activist Freeda Gnanamani, who represents the survivors, said the nature of the violence inflicted on the family was deliberate. “It was by design,” she said. “First the men were crippled, then the women were violated, marking the entire family as ‘tainted’ in public memory. That ‘stain’ is costly. Workplaces, streets, and police stations become hostile spaces. The assault may be temporary, but the social stigma persists.”

Bodies as Sites of Punishment

Raji remembers that night as if it was still happening. She recalled seeing her oldest daughter run out of the darkness wearing only a skirt and blouse. “Amma, how do I tell you all the bad things he did to me?” she said. Raji remembered feeling an intense rage.

As another policeman allegedly dragged her daughter-in-law, she said she folded her hands and begged him to let go. “I remember the smirk on his face,” Raji recalled. “‘What are we doing to her that she has not experienced already?’ I was appalled at the audacity, after he had raped my daughter while I was right there.”

Among the four women assaulted was Raji’s youngest daughter, just 17 and soon to be married. “The woman who had come from the groom’s family to see her was also made to sit in the police jeep that day,” Raji said. The wedding was called off soon after. “Later, I found another groom for her. We told him everything because what’s the shame here? He also fights along with her now.”

As Raji spoke, the husband of one of the survivors stepped in. “If someone’s leg is cut off in an attack, everyone sees it as violence. Rape is the same. It is an act of violence committed by someone in power. The shame is theirs, not ours.”

Author and social activist Shalin Maria Lawrence, who has long worked with survivors of domestic violence and caste atrocities, said the Irulars occupy one of the lowest rungs of oppression, subjected to routine torture, harassment, and humiliation. “Years of this violence have given them a startling clarity about who the perpetrator is,” she explained. “They do not internalise shame for what the caste system does to them. They recognise rape for what it is — an assault of power, not modesty.”

Raji nodded, her eyes drifting to the rocks below, the same slope where the police had dropped them back in the early hours of the morning. “We looked around and saw the pitch black. All our men were gone. We had no one. We had no friendly face around,” she said.

Raji’s husband, Rajan* (name changed to protect identity), said custody was a test of faith and moral strength. He alleged that the police had brutalised him and his children had to watch these unspeakable acts. “Every tactic was meant to break me. But as a father, I couldn’t let my family down.”

He was recently summoned again under suspicion of another theft, stirring painful memories. “I thought this was happening all over again. But now I am a new man, stronger. The khaki uniform doesn’t scare me anymore.”

Living Outside the Fence

Their public life became a trial of its own – every street they walked, every shop they entered, every employer they approached seemed to replay their ordeal. The punishment continued, with suspicion, gossip, and exclusion.

“When we would go for a walk,” one of the women survivors said, “people would say, ‘Oh, this one is still alive? How can she live after being raped? How shameless.’ They said it in front of my mother too.” She added that what hurt the most was being doubted by the neighbourhood: “They said: ‘You think these women are worthy of being raped? They aren’t even pretty enough… and they are kaattuvaasi (forest-dwellers).’”

This kind of bias is not common enough. As legal scholar Surbhi Karwa had written in her analysis for Behanbox, one of the common rape myths is based on the notion of an “ideal victim” and this bias is centred often around caste. “In our caste-driven society, a Dalit, Adivasi or Bahujan complainant of sexual violence faces uniquely different violence from dominant caste women. Their testimonies are less likely to be believed based on stereotypes of both caste and gender,” wrote Surbhi.

As we drove toward the area where the women now live, the divide between the village and the wilderness was stark. “This is where we are allowed to live,” Raji said. At a tea shop for directions, a man asked: “Why would you go there? Do you know which caste they belong to? They aren’t like the rest of us.”

Even autorickshaws refuse to come to the area where the family lives because they don’t want to be near an Irular settlement, said activist PV Ramesh.

‘If I Retort, I Will Get Fired’

Another survivor pointed out that the family is being stigmatised twice over, for their place in the caste hierarchy and their traumatising experience. “Sometimes when people realise we are standing next to them, they step away. If we interact, they insult us. So, we don’t even go to fetch water. We use river water. We just keep to ourselves,” she said.

Part of the reason why the police were brazen about attacking the women and dropping them back, Freeda said, was because they knew no one would intervene. And no one did.

Dominant caste groups refuse to mingle with or stand by Irulars, fearing ‘pollution’ and backlash from their own communities. Murugesan, an activist working closely with Irulars, explained: “People build communities with neighbours and families to depend on. But Irulars, who once lived deep in the forests, are now scattered. Even other Scheduled Castes live together in colonies; the Irulars don’t. That’s what makes them even more vulnerable.”

Uma Shankar, managing trustee of Wings to Hope, which works with Irular children near Chennai, said that even today, in some areas, an Irular is expected to walk barefoot in a dominant caste Hindu neighbourhood as a sign of ‘respect’. “They’re never allowed inside homes, except when a snake appears or a tree needs cutting. But once the work is done, the contempt returns,” he said.

Historic stigma, the ‘criminal’ tag and the theft cases frequently foisted on them – all these make it hard for the community to find livelihood opportunities. Most Irula families work in brick kilns, construction sites, waste-sorting units, agriculture, or as domestic laborers. The work is informal, low-paid, unstable, and often tied to debt. One of the women survivors spoke of how humiliating it is to ask for a job.

“One employer would call me by a caste slur and remind everyone that I was raped,” a survivor said. “I’d still do the job because if I react, I’ll get fired. And then there’ll be no food for my family.”

Though the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA), under which the Irulars were once listed as a “criminal tribe” was repealed in 1952, its legacy persisted. States, including the former Madras Presidency, introduced the Habitual Offenders Act (HOA), encouraging surveillance and policing of the community. So while the label was erased, the mechanisms of exclusion remained.

“Society paints them as undesirable at workplaces. They’re branded hereditary thieves or unclean. Even now, parents warn their children to stay away from Irular kids. If something goes missing, the blame lands on them first. And when violence is inflicted, it is often deliberate, meant to provoke a reaction that can be used against them,” said Uma.

According to the 2011 Census, Tamil Nadu’s Scheduled Tribe population, including Irulars, stands at 7,94,697, up from 6,51,321 the previous decade. Yet more than half still do not possess a valid community certificate. Without it, they cannot access reservations, scholarships, hostels, or welfare schemes– closing nearly every avenue for empowerment.

Caste-based, intergenerational trauma is rarely acknowledged. Every instance of custodial torture, sexual assault, or harassment leaves emotional debris that the next generation quietly inherits, said a psychologist working with the Villupuram local police station who did not wish to be named. For the Irulars, survival means existing outside the fence: outside the world’s protection, and often, without its compassion.

When Trauma Crosses Generations

BR Ambedkar had warned in Annihilation of Caste (1936), caste “teaches generations to accept inequality as natural, and legitimises oppression”. The exclusion, fear and trauma that the affected Irular family suffered did not end with one generation, it extended into the lives of the children.

The oldest daughter, who was pregnant during the alleged assault and later miscarried, now raises two girls. “As a woman, you are always told to be careful when you step out,” she said. “But that incident made us fear everything. So, I want my child to be bold enough to respond to anyone in authority.”

Since most Irula families work in brick kilns, the parents work long hours and take their children along — not by choice, but because extra hands are needed, and no one else is home to care for them. Children begin missing school. They start with small tasks – help mould clay, carry bricks, clean worksites, and run errands.

Disinterest sets in, and harassment from teachers and classmates further alienates them. “There are no Irular doctors, engineers, or scientists,” said Uma. “Not because they lack ambition or intelligence, but because the system has denied them access for generations. They are taught to stop dreaming before they even begin.”

She said children walk in the heat for miles to get to school, only to be mocked as ‘forest people’. “For young Irula girls, the journey is both exhausting and unsafe,” she added.

Early marriage is common, especially for girls. The oldest daughter or son often becomes a stand-in parent, managing siblings, cooking, fetching water, and making decisions about earnings. Sexual harassment at worksites and in public spaces remains a constant threat, she added.

There is a lot of distress migration in Irula families which, Shalin said, is driven not so much by the search for work opportunity as the need to escape hostility. Those who gave up their nomadic lives to settle in small towns, now relocate every two or three years when tensions become unbearable. “This constant displacement erodes stability,” she said. “It disrupts nutrition, education, friendships and everything that helps a child feel at home. People ask why we are always angry. Our caste has been demanding basic human rights for so long. We’ve learned to make our voices louder.”

Shifting Possibilities

Yet even within this cycle of displacement, pockets of possibility emerge. In some towns and on the fringes of cities, Irula children encounter enough stability to imagine a life beyond the limitations of caste.

Surya explained that the experiences of Irula communities vary across districts. “It’s not uniform everywhere,” he said. “In places like Sriperumbudur, other caste groups are a little more inclusive. Irula children sometimes mingle freely with peers, and seeing a classmate aspire to be a doctor or a leader shows them what’s possible.”

But these are exceptions.

Across districts, activists and educators are creating the conditions these families never had: safety, dignity, and access to education. Uma Shankar, who works with Irula children on Chennai’s outskirts, arranges a daily van to take children to school, provides uniforms and shoes, and lets them choose schoolbags with the colours and cartoons they like. “These aren’t acts of charity,” she said. “They want to be seen, not pitied.” Attendance of Irular kids at one school, she works with, rose from 25% to 95% in five years, with Irula kids scoring well in academics as well.

Irula families are also refusing to push children into traditional roles like snake-catching, historically used to brand them as “wild” or “criminal.”

Representation matters too. Sister Lucienne emphasised that only when Irula men and women hold leadership positions in schools, panchayats, and welfare boards will their struggles be understood in policymaking. Her team supports students in Kanchipuram, Chengalpattu, and Tiruvallur to stay in higher education and imagine futures free of caste boundaries.

As we spoke, the youngest woman’s one-year-old daughter toddled up to us, playing with a ball. We paused the conversation, but Raji said: “There’s no need to shush. Once she grows up, we’ll tell her everything. There is no shame. So ask your questions boldly. We wish we had done the same that day.”

The Weight of Waiting

Even as small changes take root in scattered pockets, the family at the heart of this case continues to wait.

It was only in 2022 that the rape case finally came to trial, but the judge had to return the error-riddled charge sheet to the police, stalling the process yet again. Meanwhile, the five theft cases against the men are only now going to trial, though they remain confident they will be pronounced innocent.

The two activists who supported the family were also accused of casteist exploitation of the women. The Court dismissed the allegations. Of the accused policemen, one has retired; the others have been reassigned to different districts.

Even in the shadow of a justice system that has kept them waiting for over a decade, Raji’s husband, Rajan, held on to hope. “We may seem lost and dejected. But I was born in Periyar’s land, where we are all equal. I refuse to believe the law can’t do the right thing.”

His words are a reminder of the gap between Tamil Nadu’s celebrated ideals of social justice and the persistent realities of caste-based harassment, custodial torture, and casual abuse. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data for 2023 underscores the scale of the problem: crimes registered under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act in Tamil Nadu rose by 68% over five years, with a 27.9% jump in 2022 alone. Custodial violence continues to claim lives — including P. Jeyaraj and J. Bennix in Thoothukudi (2020), and a 27-year-old in Sivaganga (2025).

For families like these, violence is not an aberration but a pattern. Their fight exposes the distance between political rhetoric and lived reality, raising a question that will grow louder as Tamil Nadu heads into the 2026 elections: can the Dravidian model of social justice evolve to confront the deep, persistent inequalities it once promised to erase?

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.