‘Women Are Literally And Figuratively On The Outskirts Of The Startup Economy’

In BehanBox Talkies, we explore ideas through the lens of scholars. In this installment, we interview academic Hemangini Gupta about the myths of meritocracy, flexibility, and innovation in technocapitalism

Startups are everywhere, so are tech bros. They speak the language of innovation, flexibility, empowerment, selling the vision of a tech future that is an individual’s to mould. But beneath the hackathons and the VC-fuelled unicorn craze lie histories of exploitation and indignities.

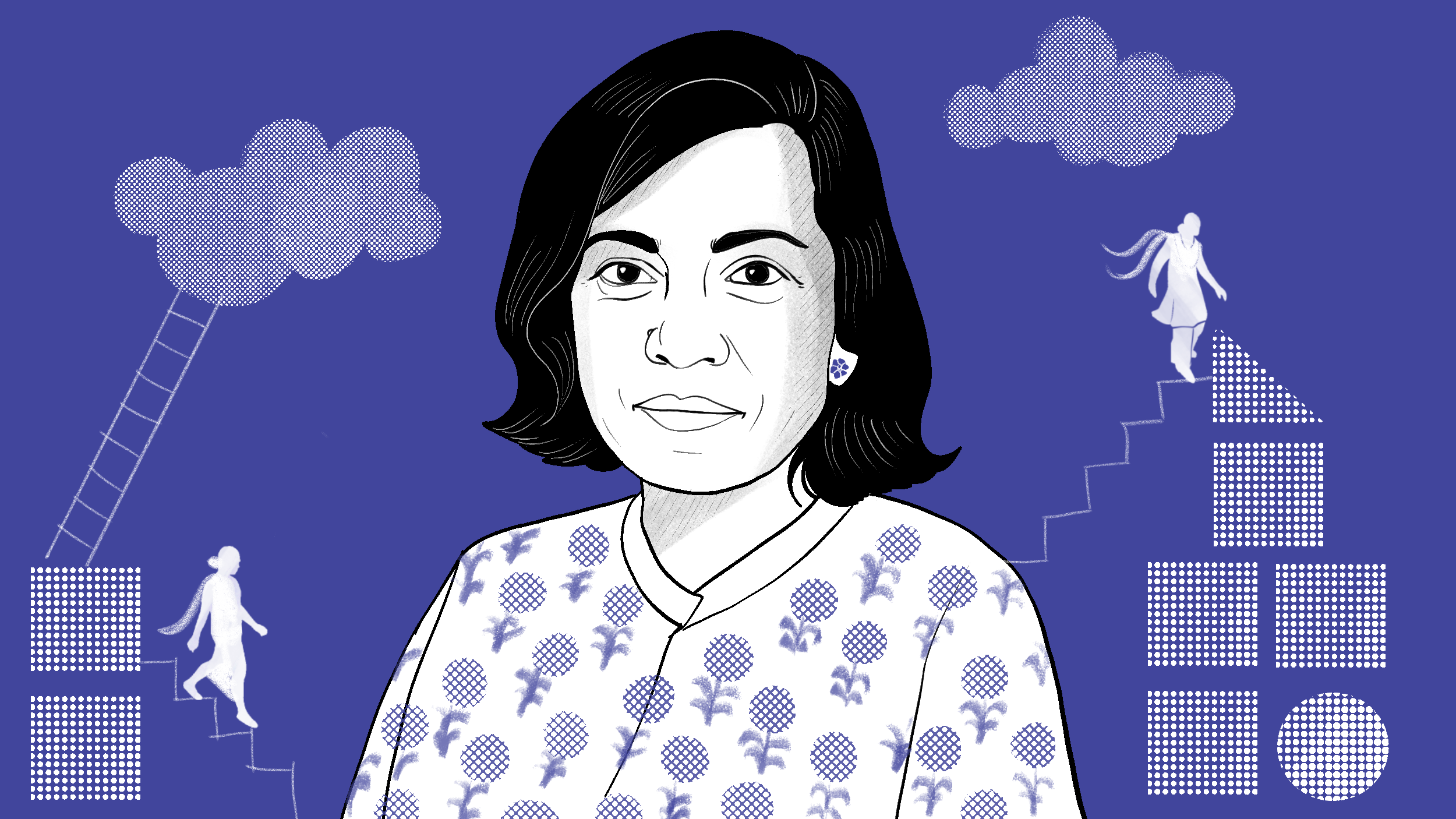

India’s current startup ecology is deeply tied to its neoliberal roots and global tech structures, says scholar Hemangini Gupta, author of Experimental Times: Startup Capitalism and Experimental Futures in India. She traces the caste and gender privileges that go into the making of a tech bro, women’s innovation and belonging in masculine spaces, and the obscure promises of ethical AI solutions. Companies have to start including workers in decision making and profit sharing to build equitable tech futures, she tells Saumya Kalia in an interview. Excerpts below.

What sparked your interest in elite tech entrepreneurs?

For my PhD I wanted to look at questions of information technology and the women in it, how they were reconfiguring some of the expectations around gendered respectability, caste and class. But IT companies were very reluctant to have an ethnographer amidst them. There were concerns around patented information and work processes, and I wasn’t able to get access to an IT company despite my best efforts.

This was also a time [the late 2000s] when a lot of my friends were moving back to Bangalore to be entrepreneurs. There was a discourse around entrepreneurship and building Bangalore as a startup city that was attractive for entrepreneurs. The city offers a combination of government infrastructure – in terms of funding actual labs and large fairs and meetings and conventions – and investment by middle class entrepreneurs, many of whom returned from the US over the last 15 years and have been trying to build an ecosystem conducive to entrepreneurs.

I eventually became interested in several ways through which Bangalore was being repositioned. One was this idea that Bangalore is not just the site for back end work but also for entrepreneurship from which creative work can be exported to the rest of the world. The second was that it was the city where many middle class professional migrants were moving back intending to do meaningful and creative work. I wanted to see what it meant for people to move to the city and to ask: how is work being reshaped in this current moment?

You speak of two types of experimentation in the book, one practised by male entrepreneurs for profit (and eventually for nation building), and one by women entrepreneurs for maintaining infrastructures of care. How do you distinguish between these?

The first half of the book is focused on understanding the male entrepreneur, a very masculine figure, and trying to unpack the expectations embedded in this idea. I attended startup meetings, networking sessions, and startup festivals where people were taught how to train themselves to be this entrepreneurial figure. This question came to me: what happens after that moment of inception, after you birth an entrepreneurial idea, how does it sustain itself? What forms of labour are necessary for that idea to grow?

Some of the inspiration came from cultural theorist Miya Tokumitsu who wrote a book about this ethos, Do What You Love. She looked at Apple as an example, how one never really thinks about who makes the Apple iPhone or under what conditions they make it. So the second half of the book focuses on a particular entrepreneurial company and tracks the everyday life and work of people employed there. I found that the expectation was that all employees become some sort of entrepreneurs themselves.

The values and habits of the male founder were normalised and expected to be adopted by everyone – they were expected to be experimental with the food that they ate, how they held themselves, the kind of leisure and creative pursuits that they’d have. There was this expectation that our bodies would be prepared for an entrepreneurial life, which is not just about work.

The book contrasts these two kinds of experimentation, one by the male entrepreneur who heads the company, who enjoys the profits of the company, and the other by women who experimented for survival. Most of the women were young, middle-aged employees; none of their parents, certainly not their mothers, had professional office jobs. For them, the experimentation was not just in being with each other and trying to figure out how to move in these spaces of leisure – it also became about experimenting with their personal lives. They took a lot of risks in terms of who they made friends with, how they fell in love or how they got divorced. The workers in the company came together to form these infrastructures of care and socialising, and it’s through that that they survive this everyday expectation of experimentation in the office.

Do women entrepreneurs enable or upend the model of startup capitalism?

I still ask myself that question. It is sometimes phrased as, is there an alternative to capitalism? At the end of the day, people want to know if there is a possibility for change and at this moment, I don’t think there is. We are encountering women who are entrepreneurial but that doesn’t necessarily mean the nature of entrepreneurship is changing. Women are entering a world that is already dominated by masculine expectations around how they are available to work, where they can work, and how many hours they put into it.

But then there’s also the question, are these women doing something to undo from within the expectation of capitalism? The answer is probably they were working within it. For instance, on days when you could order food at IT companies, women employees would often order biryani but the CEO would come in and say: ‘Come on guys, you can’t just order the same food every time. We’re a global company. Why are you doing the same thing every day?” To him, it meant you’re in the startup neighborhood, you should be eating experimentally. But I think among women was the understanding that there were others with you who were also equally a bit tentative and ambiguous about entering these new worlds.

So they took that ambiguity with them, and sometimes it manifested as a tentative approach to work, which was not really the gusto and the energy that the entrepreneur expected from them. Sometimes they just refuse the terms of entrepreneurship. One of the schemes in the office was to sign up for a class to enhance yourself – maybe learn French or a new skill – but nobody ever signed up for these classes. The entrepreneur was always very confused because he’s giving them an opportunity to be ‘neoliberal’ in a sense, to remake themselves as flexible people in a market that’s constantly requiring new skills, and yet, people are just refusing that. I understood it almost as a refusal of that idea that one should constantly work to better themselves and produce more profit for the company. Women wanted to have fun at work – they wanted to learn things – but they were also very emphatic about living in the moment and not extending themselves toward a future that they could not anticipate or control.

Other times, they’d plunge into the worlds that they were expected to plunge into, like, literally, when they went on an off site trip of water rafting. None of them knew how to swim and they were terrified but they came together, held on to each other, and participated in this ‘team building’ activity.

There weren’t uniform ways in which women entered these worlds of startup capitalism, but their refusal to follow a coherent, linear pathway is a sort of undoing of its terms.

These ‘techno-entrepreneur’ figures, what privileges do they hold?

I should have more emphatically called it tech bro culture. At these startup meetings and festivals, it was very much the tech bro, this figure who was always available, who was centered. At this incubation lab I visited, six companies pitching an idea were telling a venture capitalist why their company was amazing. To one of them, the venture capitalist asked how their company was ready for the market, and the person said they have people working around the world, they’re always online, they’re 100% here. Even at three in the morning. This is one example of how the expectation around startup entrepreneurs was that they would always be present, and I compared that with some of the women entrepreneurs who worked very different hours. They weren’t up at three in the morning – they were up at six to pack lunches for husbands and children, then maybe do some work for the startup before others left for office and school, and then attend networking meetings, which were almost never possible for many women.

Even just being able to participate in a startup meant being able to meet collaborators, to network, to meet venture capitalists – but that physical mobility through the city was shaped by where they were in their lives and who they were. Middle-class married women tended to be literally and figuratively on the outskirts of the startup economy. On the other hand, the tech bro figure, or the figure who was ever available to participate in startups, was often a young or middle-aged man, who didn’t have care responsibilities and could really be mobile, both in terms of time and space. The city itself was shaping who could access these dense worlds of startup networking and who couldn’t.

Can you talk about the ‘cyber coolies’ you write about in the book? And the presence of caste ideas and dynamics in entrepreneurial spaces?

When it comes to entrepreneurs or most forms of middle class work in India, nobody wants to talk about caste. It’s almost like you’re embarrassing them by bringing up something that is so ‘archaic’. There’s this belief that India is moving into a future that doesn’t rely on caste differences – a future that is prized on merit and what people can do.

In my conversations, people didn’t bring up caste but there were explicit references to this figure of the ‘cyber coolie’. People would say they were interested in “ideas” or “management perspectives,” not in being cyber coolies— a coolie, in that imagination, is someone who is told what to do. Historically it’s a figure of racialised labour who is sent to plantations to perform a certain kind of work. Some even connected it to visa regimes like the H1B visa, under which many Indians get to travel to the US for work but cannot then leave the company and work elsewhere unless the company sponsors your ability to be mobile. So as entrepreneurs, they wanted to distinguish themselves from labour that is attached to a higher power – they wanted to say we are capable of being mobile and independent of the racialised regime of technology work.

There were constant hierarchies being assembled between work that was creative and intellectual, and work that was assigned to you, task-based, and what they considered menial. These hierarchies are themselves expressions of caste-based labour because they distinguish and assign different values to the labour of the mind from the labour of the body.

Even though people didn’t explicitly talk about caste advantage or disadvantage in differentiating work according to these hierarchies, these caste imaginations that galvanised work were considered valuable.

Why did you shift to telling the story of startup capitalism from the point of view of workers?

There’s always an excitement around entrepreneurship, that we can reshape historical age-old inequalities if we use this technology correctly. We pay a lot of attention to TV shows that celebrate and reward entrepreneurs and the million-dollar-idea. That misses the very next step: what happens after you have this brilliant idea? In a public sphere and a realm where people are constantly exhorted to do what they love, be innovative, take risks, it’s upon us to ask that second step-question.

India is seen as a superpower due to its technological prowess and convenience of getting things delivered within 10 minutes, but the question is who’s bringing this convenience, what kinds of labour are being recruited, what is the precarity required for this market to function?

Globally, we hear these ideas of “do what you love” and work hard from tech CEOs but these sit uneasily with the fact that India’s IT and ITeS sector has witnessed its steepest layoffs in decades. How do we reconcile these two realities?

Those things are fundamentally linked – the more precarity there is, the more entrepreneurship is emphasised. Once people no longer have the ability to imagine stable jobs, entrepreneurship becomes one way to sidestep questions of ensuring basic benefits or job security, or of a State that provides for people who might not be in informal or long-term employment. The more there is precarity, the more there is austerity, the more the State retreats from providing essential goods and services at scale, the more there’s the expectation that people will just innovate or be entrepreneurs to support themselves. In the absence of there being more stable infrastructures of work, it’s this speculative idea that you will just make it big that really takes hold in people’s minds.

Entrepreneurship and platform work celebrate “flexibility” and “independence” but these ideas conceal a deeper feminisation of labour where people are working more in precarious roles but earning less. How has the language enabled this shift?

It’s making workers precarious, and there is a sort of responsibilisation also. In my research, workers were often referred to as ‘travel consultants’, and it wasn’t clear to me why they were consultants when they were employed by the company. These terms became really important in taking away people’s identity as workers or as employees; there was no shared understanding that they were participating in conditions of work.

By thinking of themselves in these sort of privatised terms of ‘partners’ or of ‘consultants’, there was also an understanding of one having control over one’s labour. A consultant is someone who can decide the terms of the consultancy, what they earn, when and how they work. None of these were things that people could actually do at work but by calling them consultants, companies passed the circulating belief that you are in control of the terms of your work, in a way that you’re actually not.

If ESOPs are a form of recognising labour, what do you make of unions demanding ‘worker IPOs’ and a say in decision making?

Concrete material redistribution has always been a fundamental worker demand. If people are invited to participate as equals, they should literally have a say in how the company is run, give feedback on management structures, and share in monetary benefits as well.

In the companies I studied, people are told to take ownership of their ideas, but they are never given extra money for having taken on that role; it’s just a sort of a nebulous idea that the company is yours and you should participate in it.

If a company wants to have egalitarian norms, it will have to let people participate not just in decision making, but also in sharing profits. And to recognise that in order for an entrepreneur’s ideas to hold, people have to take great risks.

Do you see any continuities or disruptions in these histories in the present moment of global AI labour?

I’m curious to know whether my arguments hold in this new moment of data annotation work. In Bangalore and other parts of India, we’re seeing experiments with impact sourcing and ethical AI work. Companies are working with self-help groups to assign data work to marginalised communities and there are efforts in thinking about redoing the terms of data work in that some returns go to the communities and that the conditions of work are not exploitative. These promises are very compelling, especially coming from the Global South, but we’re still figuring out if these projects can really materialise.

What feels continuous with the histories I wrote about is this very visible realm of entrepreneurs who are interested in wanting to ‘remake’ AI work as something that’s well paid and dignified. I’m thinking of initiatives like Karya [which claims to be the world’s first ‘ethical AI company’ that offers digital work to rural Indians] and others who have been foregrounding ethical AI – they are literally visibilised in terms of a TIME magazine cover but also very visible in the public sphere.

But when you look closer at the broader realm of AI work being sent to Asia and Africa, we have to ask: do we know about the actual conditions of this world and how these promises hold in practice? If we begin to ask who does this data work, we’ll find it’s people who are caste disadvantaged, people who have been laid off from agricultural work because of over-extracted land, people who don’t have much choice in the conditions of their work. We might find a very similar dynamic to the book, where there is a tension between the visibility of entrepreneurs who speak about remaking work and the invisibility of the racialised and gender labour that make this work possible.

There’s a lot of potential for this work to be better paid but there’s never that second-level question: does this change the conditions of work, does it offer protection, and who bears the environmental costs of these data infrastructures?

What is the role of the city in realising these tech futures?

I have different responses to this question.

At the 4S conference recently, Ashique Ali Thuppilikkat, Aditya Nayak and Aditi Vashistha presented a paper on how even as platform economies grow and are distributed across the city, there is still a need for massive dark stores to stock produce. But where are these dark stores located? It’s very difficult to find them – they’re not explicitly labelled, they’re not on Google maps. The authors tracked these stores using various forms of geospatial mapping and found them often on the edges of peripheries of low-income neighbourhoods. It raised interesting questions about how even as we imagine that platform work is moving to not be site-based, it still requires urban spaces in order to cite certain key logistical points, which would then influence the rental economies in those areas. It plays a role in how workers might access the space and where they might live and how they are priced out of the city so to speak.

The second has to do with how workers move through the city. In my research on beauty platform workers in Bangalore, I found that even though there’s not necessarily an office or a central site, your movement through the city becomes significant to how much you can make and where you need to live to have access to the right kinds of clients. The city’s role in labour is constantly changing. In Bangalore, in earlier moments technology work happened at the outskirts of the city in IT Parks. Now the work, rather than being concentrated at a particular building or in a particular site, is distributed across the city. Even as workers move through the city during traffic, rain, and extreme heat, the city still retains significance as a site of everyday work. It’s no longer the same kind of site, but it’s the streets and the buildings and the rental economies that shape how workers have access to work.

Do these spaces hold the possibility of collective bargaining?

Anthropologist Lilly Irani’s work shows that when we speak of innovation, there is a certain scale at which we’re imagining an idea to be able to move. She examined that for small local ideas – like keeping water cool in a clay pot – to achieve the status of innovation, it was required to scale and travel out of a local circuit in order to be recognised by the government and international consortium.

That expectation that innovation must scale, grow and multiply is inherently in tension with an idea of democratic participation or opening up something to a larger number of people. If to innovate is to celebrate and prioritise a scale, feminists might ask: what about something that is small, local and meaningful but not necessarily something that everybody wants, or that 1.2 billion people need?

Entrepreneurs in Bangalore often say a good idea is one people may not need but they may begin to want it. This combination, of innovation being necessarily at scale and it being something that can be made desirable, to me those two things sit in tension with our democratic imagination: to enable diverse voices, abilities, levels of participation to be seen and recognised.

We would love to hear about your experiences and perspectives of the IT and ITeS sector. Write to us at contact@behanbox.com.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.