Data On Violence – What It Tells Us And How It Can Be Used Effectively

One Stop Centres for victim-survivors of gender violence can use their own data to strengthen response services

What can administrative data tell us about gender-based violence, the victim-survivors, and their access to services and justice? UN Women says that the conscientious use of administrative data—the data collected by government or non-government bodies providing services to those seeking help—can strengthen the response to gender-based violence (GBV). This can include data collected by the police through First Information Reports, counselling services provided by an NGO, or government programmes like One Stop Centres.

In 2024, I set out to study the functioning of One Stop Centres (OSCs), which were designed to provide one-stop access to justice for survivors of gender violence. Women, apart from finding emergency shelter and psycho-social counselling, would also be able to access services offered by the police, courts, and hospitals from the OSC instead of navigating them independently.

In India, our knowledge of the existence and nature of gender based violence comes primarily from two sources. The first is the national statistics on crimes against women, released annually (not since 2022) by the National Crime Records Bureau, which aggregates reported offences filed by women at local police stations. The other source is the National Family Health Survey, a representative survey that collects data on women experiencing physical and sexual violence. But, these mechanisms have several limitations, which include underreporting of violence and even categorising of what constitutes gender-based violence.

My study, which aimed to understand whether OSCs were meeting their intended promise of providing integrated services, suggests how administrative data could be used to inform response systems for GBV. Through administrative data collection and ethnographic observations from two OSCs in Delhi and Mumbai between October and December 2024, I discuss what data can tell us about women’s access to OSCs and their different services, the types of cases that get addressed, and the quality of response they receive.

While administrative data cannot estimate the extent of violence and, hence, cannot be used to measure the actual prevalence (typically documented through direct surveys with women), it can suggest how women are using specific services, existing gaps in service delivery and ways to address these.

The existing public data on the OSCs lacks nuance. The Mission Shakti (the umbrella programme on women’s safety and empowerment of which OSCs are a part) dashboard does not provide disaggregated information on the centres’ operations. Since government permissions restricted us from collecting administrative data at the field sites directly, I filed Right to Information (RTI) requests with the state governments of the OSCs in this study.

For the ethnographic part of my research, I chose OSCs in Mumbai and Delhi for their distinct set-up. The Mumbai OSC is located inside a public hospital, while the one in Delhi is inside a bureaucrat’s office complex. Their set-up has implications for response, as I discuss later. Both were set up in 2019, four years after the programme was launched. Maharashtra has 55 operational OSCs, while Delhi, a smaller state, has 11 centres.

Government data show that more women are accessing OSCs over time. The numbers increased from 1.47 lakh in 2021-22 to 2.29 lakh in 2024-25 (till 31 March 2025). In Delhi, the number of women accessing OSCs increased by almost 70% (6,945 to 11,785) between 2023-24 and 2024-25. In Maharashtra, however, it saw a decrease by 26% (from 9,894 to 7,282) in the same one-year period.

There could be two reasons for the decreasing trend in the past year for Maharashtra: one, OSCs have become dysfunctional or are shutting operations due to resource constraints like delayed staff salaries, layoffs, etc.; and two, fewer women now trust OSCs to support them. One of the two OSCs in Mumbai run by an NGO had to shut shop in 2023 because of a change in government rules which disqualified NGOs from participating as implementing agencies, per conversations with the staff.

But, the rules of the game are vague. The Mumbai OSC, where I conducted the fieldwork in December 2024, was still being supported by an NGO because the government knew they could not supplement their expertise, said the NGO’s representative.

The OSC programme was first piloted in 2015 with 36 centres. It has since grown to 820 centres in the last decade. While the need and urgency to build GBV support systems are apparent, changes in scheme design and resource constraints have pushed the burden of implementation on the OSC’s staff (centre’s administrator, caseworkers, counsellors, advocates, and helpers), who are at the frontline of service delivery. And, an overburdened and underpaid frontline is often unable to meet the demanding nature of their roles.

Field Insights

The RTI data show that the number of women coming to the two OSCs has been increasing over the years. In 2019, the first year of its operation, only nine women came to the Delhi OSC. This increased to 405 women in 2024. In Mumbai, only 28 women came in 2019, which increased to 799 in 2024.

“Since the other OSC has shut down, those cases have come to us. But it is difficult to manage so many cases,” said the administrator running the OSC in Mumbai. Her centre receives anywhere between 60 to 80 cases a month. The Delhi OSC handles almost 40 cases monthly, one of the highest across the OSCs in the city, said its administrator.

Given their set-ups, both are uniquely placed in offering and receiving services. For instance, the Delhi OSC also tries to resolve senior citizen grievances related to property disputes. It receives the highest number of ‘missing recovery’ cases (cases where a person goes missing, typically a kidnapping complaint), compared to Mumbai, which has the highest cases of domestic violence. This is true for all years since 2020.

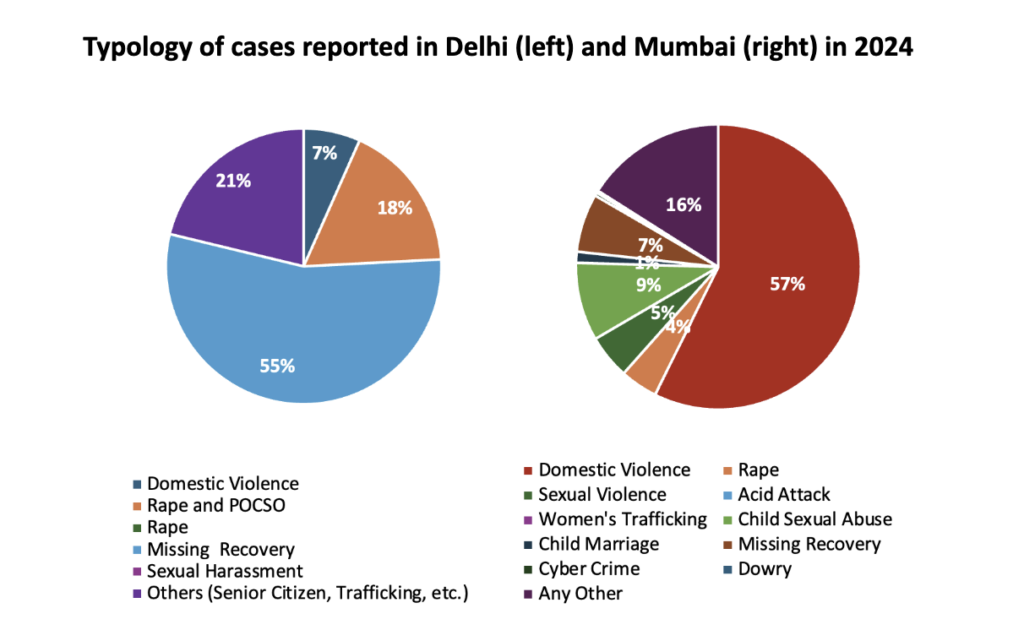

The figure below provides a detailed breakdown of the typology in which cases are reported at the OSCs. In 2024, 55% of total cases were of missing recovery, followed by “others”. For Mumbai, 57% of cases were of domestic violence, followed by those under “any other”.

All OSCs have an IT officer. One of the IT officers took me through the Mission Shakti portal, where they upload case-related information. After a case is identified by the caseworker or counsellor, the IT officer marks it under one of five categories: ‘Civil Crime’, ‘Cyber Crime’, ‘Domestic Violence’, ‘Sexual Violence’, or ‘Other Gender-based Violence’. She also has the option of further sub-categorising cases into over 100 specific ways. Some of these were medical termination of pregnancy, burns, mental health, workplace abuse, shelter abuse, etc.

The RTI response on administrative data I later received from both OSCs, however, provided limited information on the specific types of violence women experienced. Cases under “others”/”any other” increased almost tenfold for both OSCs since inception until 2024. Delhi only provided five specific categories, whereas Mumbai provided 10, as the above figure shows.

As previously mentioned, OSCs integrate multiple services, including psycho-social counselling, emergency shelter, police assistance, legal counselling, and medical aid.

All women received psycho-social counselling in the Delhi and Mumbai OSCs. But, for other services, the ‘one-stop’ function of the centres seems limited. For instance, of those women who sought OSC support in Delhi in 2024, 91% received shelter and 24% received legal counselling. Only 2% women received medical aid and 1% received police assistance. In Mumbai, on the other hand, only 13% of women received shelter services in 2024. A higher proportion, however, received legal (54%), medical (24%), and police (23%) support.

The reason for these differences is the set-up, as previously indicated. In Mumbai, most cases come from the hospital, while in Delhi, they come from the police. In both these situations, women are already receiving police and medical support, and the OSC does not have to refer women back to these sites but only coordinate on their behalf.

Coordination, though, is a time-intensive task. It is one of the key services performed by the OSC’s frontline to ensure that all institutional actors are doing their jobs. The frontline in Mumbai would often be accompanying the women to drop them off at a long-term shelter, conducting ward visits to identify new victim-survivors or meet those already registered at the OSC. The Delhi OSC, until October 2024, did not even have a vehicle of its own. It is, however, uncommon for them to physically accompany women to these different sites, as the police are responsible for handling the majority of the cases coming to their centre.

Missing recovery cases are the highest at the Delhi OSC. Filed by the parents for their minor girls who ‘run away’ from their homes, police typically record these cases as kidnapping. The police put up these girls at the OSC while the formal procedures are taking their course. Hence, for this OSC, the provision of emergency shelter services is high.

One of the girls at the Delhi OSC, during my fieldwork, had been staying at the centre for more than two weeks. Her Investigation Officer had been on leave and, hence, the OSC had to keep her for more than the five-day limit of residence allowed at the centres (per guidelines). The caseworker told me that the girl had been frustrated and wanted to go back to her husband. Her father had wrongly filed a kidnapping case.

Most cases in the Mumbai OSC, on the other hand, are referred by the hospital. A lot of cases have “hidden violence”, said the administrator, and, so, it is important to look at every case closely. It is through a series of rapport-building conversations, while women are still admitted to the hospital, that they reveal their experience of violence to the OSC’s counsellors and caseworkers.

Resource Constraints

The Delhi OSC does not have a full-time legal counsellor present at the centre, despite it being mandated in the guidelines. Similarly, all OSCs must have at least five beds, but the Mumbai OSC has only one.

The set-up influences the extent to which victim-survivors can be supported, too. In Delhi, women with poor mental health are actively shunned because there is no verifiable medical authority inside the OSC or the bureaucratic office complex where the OSC is located. In Mumbai, such women are taken to the psychiatric ward for a comprehensive assessment, I observed. The caseworker added that without thoroughly understanding women’s backgrounds, they cannot gauge how to rehabilitate them.

Moreover, even though the Mission Shakti portal allows for granular data collection, it is not being recorded. Maintaining comprehensive case-related information can inform future response strategies, too. But, as I witnessed on the ground, most such information gets lost in the physical copies of individual cases, never translating digitally. Especially the detailed, written case histories maintained by the counsellor. These are important to understand women’s overlapping vulnerabilities, such as when abuse is coupled with homelessness, care responsibilities for dependents, etc.

An important thing to consider here is the confidentiality of digital accounts. The previous Mission Shakti portal allowed maintaining confidentiality by only assigning a unique ID to every woman. The new portal also allows entering the woman’s name along with generating a unique ID. To this, the IT officer said that this helps with data entry as the OSC staff have already developed a personal connection with her. Importantly, the physical copies only mention the unique ID, not the woman’s name.

Way Forward

The low-hanging fruit is to accurately identify and learn from OSC’s data to improve support systems, as this study shows. In their years of operations, OSCs have developed independent ways of identifying and resolving cases. Despite its advantages, this is also perhaps a missed opportunity because bureaucratic settings are resistant to change. This issue is complicated by the limited recognition of the care burden that those at the frontline undertake.

“We function like the police and have to respond to all cases urgently,” stated one of the administrators, despite not receiving any funds for running their centre since the beginning of the last financial year. As I discuss in detail in another article, the response has become apathetic to victim-survivors’ needs.

It is important to acknowledge the frontline’s coordination role, too. Current data suggests that a service is counted only when it is routed through the OSC first. For instance, only if a girl were coming directly to the OSC and the staff were to connect her to the police, would it be registered as a service performed by the OSC. But, OSCs are always coordinating with different actors physically and telephonically, despite how a woman or girl reaches the OSC, as I witnessed at the centres. Recognising this as a critical task can help take stock of the frontline’s pre-existing care and administrative burden and inform hiring practices, training, workload distribution, etc.

Lastly, by not regularly updating data on violence against women, both at the national and programmatic levels, the government evades accountability to reform these systems. Gaps in programmatic data could be inhibiting women from making informed choices about the options available to them for seeking help. OSCs were imagined to improve access to justice for victim-survivors, and they must begin translating this into practice by learning from their own data.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.