Mapping Tidal Floods: How Women in Coastal Kochi Villages Are Building Climate Resilience

In the flood-prone coastal villages of Kochi, as rising sea levels threaten homes and livelihoods, women are creating community-driven solutions to the climate emergency that the state is only beginning to acknowledge

Geetha, 60, wakes up before dawn everyday to a familiar anxiety — the invasion of the night’s high tide into her home. The faint, briny smell of salt water lingers in the air as she steps out of the bed onto a watery floor. She needs to complete all the household chores, including cooking for her large family that includes her husband, children and grandchildren, before she leaves for work at 7:30 am, wading through the standing flood waters.

Every step of her morning routine is shaped by the relentless presence of the tide. As she makes her way to work, Geetha, a Dalit resident of Edakochi in Ernakulam, who works as a sweeper in the Kochi Corporation, again has to negotiate the grimy flood waters.

“The road from my house to Aquinas college (500 meters) remains flooded in the morning on most days. I have to hitch up my saree up and walk, else it gets completely wet,” says Geetha. She says can feel the grit and debris of the remnants of last night’s tide that never receded fully swirling around her ankles. Each step she takes is deliberate, her feet searching for solid ground.

As she approaches the main road, there is a small comfort waiting for her. A kind resident who lives near Aquinas College, leaves a bucket of clean, fresh water outside the gate. It allows her to wash off the grime sticking to her feet. “I have neither seen her nor know her name. But she understands our daily struggle,” says Geetha.

Across Kumbalangi, Edavanakkad, Puthenvelikkara, Ezhikkara, Vypin, Edakochi, and other low-lying coastal villages of Kochi, tidal floods are shaping the everyday lives of people, their brunt mostly faced by women. Rough estimates suggest that tidal flooding has affected over 20,000 people across 23 gram panchayats, say experts at Equinoct, an NGO that offers science-based solutions to climate change impact. The state government, however, is yet to map the scale and intensity.

Now women in the panchayats affected by tidal flooding, including members of Kudumbashree, the state’s women led poverty eradication program, are coming together through collective actions like community mapping and theatre to advocate for and bring attention to their vulnerability to the state government.

Backed by a non-profit that works on the science of flooding, the women from affected regions are now learning to observe, measure and map tidal floods, as we detail later.

Kochi’s Crisis

Tidal flood is the temporary inundation of low-lying coastal areas during exceptionally high tides, often occurring during full or new moon days. It occurs when rising sea levels combine with tidal forces and local factors, causing water to overflow. What was once seen in the month of Vrischikam (November- December) in the coastal region of Kochi, has now turned into a prolonged phenomenon, extending up to May, until the onset of the monsoon.

The coastal belt experiences two tides a day, usually at an interval of 12.5 hours. With each rise, salty water quietly seeps into homes, floods narrow lanes, disrupting lives.

The melting of the ice sheets due to global warming is one of the primary reasons for rising sea levels. For Kerala, which lies along the Arabian Sea, this presents a significant challenge. According to projections released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2023, many key coastal regions could be submerged by 2050.

Between 1874 and 2004, the sea level was rising at a rate of 1.06 to 1.75 mm per year, per the IPCC report. That rate has now increased to approximately 3 mm per year. Based on projections from a Digital Elevation Model released by Climate Central, a science organization based in New Jersey, districts like Ernakulam, Kottayam, Thrissur, and Alappuzha in Kerala are at risk of falling below the sea level. This year’s tidal flooding was significantly more severe than that of the previous year, according to data from the tidal gauge station at Willingdon, Kochi. From 2011 to 2022, there were only 11 days when the tide rose above 1.5 meters. In 2023, this occurred twice. However, in 2024, it increased to 10 times, and in 2025, it rose to 23 times. In January 2025 alone, the tide rose above 1.5 meters on 15 occasions. Additionally, for the first time, the slack tide persisted for around two hours..

Kochi is renowned for its backwaters, which are interconnected lagoons and canals paralleling the coast. Due to the presence of estuaries and backwaters connected to the sea, the tidal rises and falls are deeply intertwined with the lives of those living here. However, it has now evolved into a climate emergency that is severely affecting the lives of the coastal population in Kochi.

Life Amidst Climate Change

Women bear a disproportionate impact of this crisis, as we said earlier, including a rise in the care burden. Sandhya, a 46-year-old domestic worker employed in Kochi city, has to wake up at 4 am to finish her household chores before she leaves for work at 6:30 am. She has no time to clean the debris brought in by the tide in the morning.

“Only after the water recedes can I clean the house. If I wait for it, how will I make it to work?” she asks, as she trims the fronds of coconut trees. As soon as she returns from her exhausting work day, without a moment’s rest, Sandhya dives straight into cleaning her home. It takes her a couple of hours to do this but she knows it is futile effort because the next tide is around the corner.

“I don’t see any escape from this. We can’t even sleep peacefully here without ensuring that household objects like utensils and footwear are secured high above ground. If not, by morning everything will be floating through this panchayat.” Sandhya says.

Tidal water contaminates drinking water, damages crops, erodes the land and makes life a constant struggle against an unpredictable, ever returning force.

Due to constant contact with saline water, skin conditions like eczema are very common. The tide also brings waste discarded by people living in other parts of the city into their homes and courtyards. Seboline, a moisturising cream, is their solace.

There are other social and familial burdens for women. Maria Soni, 29, and her twin sister who married siblings from the same family in Panangad in Kochi, say they are taunted by their in-laws about the flooding in their filial home. Often, they are not allowed to visit their parents and when they do, it is on the condition that they would stay with a relative nearby whose house does not flood.

Most women in Kochi’s coastal villages who arrived here after marriage, at a time before tidal flooding became a daily hardship, complain of feeling ‘stuck’ now. Shyama, a 34 year old Dalit woman who married into Kumbalangi from Chemmannad village 11 years ago recalls: “There was no flooding when I first came here. But for the past five or six years, during high tide, water rises from the canal behind our house. The land where the house stands has sunk.” she says.

There are economic costs too.

Shyama’s 61-year-old mother-in-law, who works as a cleaning staff at YMCA (Young Men Christian Association), took a Rs 20,000 loan from there and an additional 80,000 gold loan from ESAF Cooperative Bank to raise the ground of their house. “But every year, the house keeps sinking lower because flood water accumulates in our yard. So, we have to spend Rs 10,000 annually to raise the ground further,” says Shyama.

Vinaya, a 37-year-old Anganwadi teacher from the Kumbalangi gram panchayat and her family had to apply for constructing a new home under the Livelihood Inclusion and Financial Empowerment (LIFE) housing scheme that provides safe and decent options to the economically and socially marginalised people in outlying, coastal or plantation areas. “Usually, people build just one house in their lifetime. But that’s not possible here,” she says.

The house Maria Soni’s father built with the money he earned from the Gulf nearly 35 years ago has now become uninhabitable due to salt water intrusion. Back then, the family would simply mop the house clean but now that is not enough – they had to install a motor pump to drain the water out of and spend an additional Rs 2.5 lakhs to raise the level of their yard with truckloads of soil. Eventually, due to excessive usage, the motor broke down too. Finally, the family had to move to a two bedroom house on rent for Rs 8000 per month, when the roof of their home collapsed. Now, the only things left in their old house are the floodwater and an image of Jesus.

Climate Action In an Era of Rising Tides

For the past five years, Equinoct has been working with the women in the flood-prone communities to build solutions and resilience. The issue of tidal flooding first came to Equinoct’s attention in Ward 13 of Vellottumpuram during the devastating floods in Kerala in 2018, while they were setting up a riverine flood monitoring network along with the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation’s Community Resource Centre in Puthenvelikkara.

“At that time, there was no data on when and how [high] the water would rise,” explains KG Sreeja, research director at Equinoct. “In the initial phase, we used the measuring tape used by tailors to measure and understand the water level rise in 18 houses. That was the first-ever intervention in the issue of tidal flooding.”

With the support of the Fulbright Fellows Alumni Engagement Innovation Fund from the US Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, the initiative transformed into a rights-based campaign. As part of its first phase, a people-led study on tidal flooding titled ‘Community Co-Creation of Resilience to Tidal Flooding in Ernakulam District’ was launched in three gram panchayats– Kumbalangi, Ezhikkara and Puthenvelikkara.

To understand the extent of the tidal flooding phenomenon, Equinoct designed a calendar to track the cadence and intensity of water level rise. “When we approached the panchayats requesting special committees to help with calendar distribution, they assigned Kudumbashree workers, ASHA workers, and MGNREGA workers. Around 90% of those who came forward were women,” says Sreeja.

Shyama, a member of Kudumbashree, first came to the Kumbalangi panchayat office when she heard of the awareness classes about tidal flooding. “I wanted to understand why the water was rising. I felt it was my responsibility to take action for the sake of the next generation.

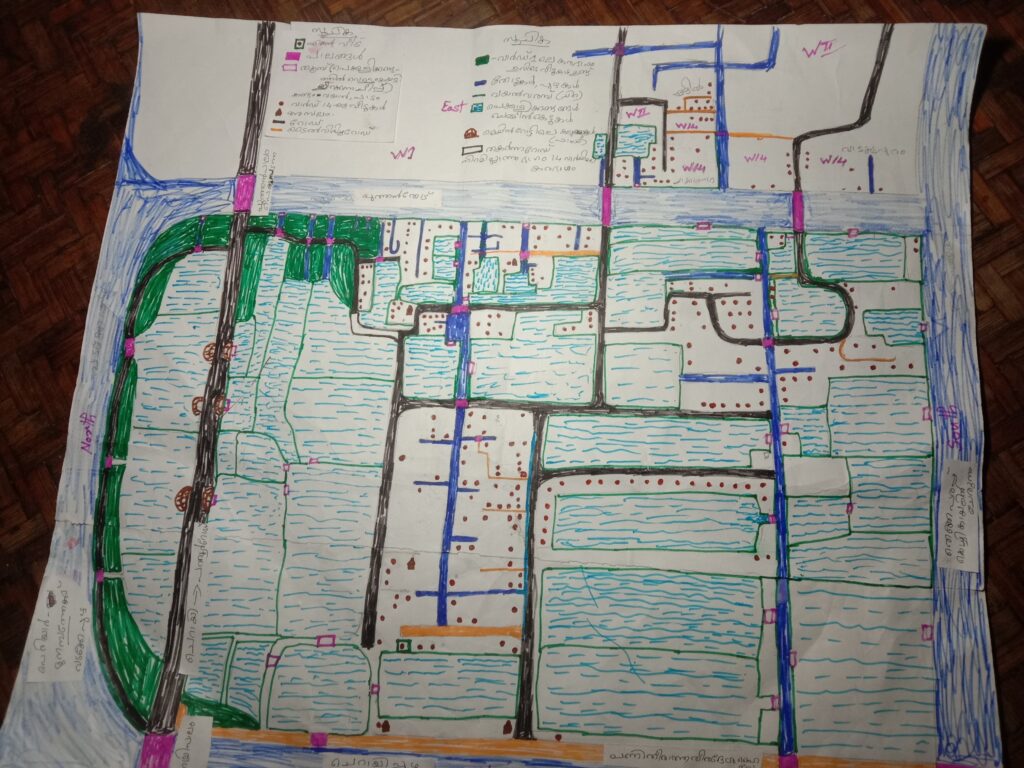

The women were trained and assigned with distributing the calendars across all wards affected by tidal flooding to record the data. A year later, based on the data recorded in the calendars, the women set out to create community tidal flood maps.

Co-creating Data, Maps and Resilience

In the beginning, it was mainly members of the Kudumbashree network who attended the training sessions. Most of them who had come to the flood prone villages after marriage, and only knew the road to their marital home and little beyond that, recalls Sheela, a 58-year-old Dalit resident of Ezhikkara panchayat and the eldest member of the community mapping team. Sheela also works as a thozhilurapp employee under the MGNREGA scheme.

“One day, they came to me and said, ‘Sheelachechi, we really don’t know where the roads or canals are in this place. Can you draw it out for us?’ That’s how I started doing the mapping,” says Sheela who began the mapping work after the devastating Kerala floods in 2018.

The Ezhikkara panchayat, located about 3km from the Cherai beach, that was hit by the 2005 tsunami, formed a disaster management committee that began mapping for making disaster response efforts more effective. Sheela’s mapping skills came in handy – given a chart paper and a few sketch pens, she can deftly mark the canals, houses, and fields in a village.

Video documentation of the tidal flooding was also carried out in these panchayats under the leadership of Kudumbashree network. Manjula Bharathi from the School of Habitat Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, conceptualised and implemented various community-based approaches such as community mapping, video, and theatre. These visuals became direct testimonies of the travails of people during tidal flooding.

Soon women who were not affected by tidal flooding joined the exercise too. “Water doesn’t enter my house but I came to know of the problem through the training,” says Prasheeda from Ezhikkara.

While the Kerala Disaster Management Authority is yet to recognise tidal flooding as a climate change-induced disaster, the coastal population managed to get some relief. On March 25, Ernakulam district panchayat budget allocated Rs.2 crore to build ring bund roads in the tidal flood affected panchayats. The local body of the Vypin constituency notified that the affected families in the coastal regions of Ernakulam district could now apply for compensation for damage to their properties after submitting evidence.

“Photos were taken before and after the tidal flooding, and assistant engineers from the panchayat conducted valuation visits to assess the damage. However, the compensation that people are set to receive is very small. Hence, economically weaker sections of the community are left with no real means to recover,” said Susan Joseph, president of the Kumbalangi Grama Panchayat.

In Kochi’s coastal belt, the majority of those affected by tidal floods belong to backward classes, including inland fishing communities, Dalits, and other marginalized groups who primarily depend on daily wage labour, construction work, fishing, and related livelihood. This leaves them vulnerable to economic shocks, explains Susan. That this crisis can lead to long-term, structural poverty and marginalisation of these groups underscores the need for more equitable and comprehensive recovery policies, she adds.

“We know that rehabilitation is not easy. This is our escape plan. We made this map so that someone can come and rescue us if the tide rises,” said Sheela from Ezhikkara.

[This story is part of a new series “Climate Leaders: Women in Local Climate Action”, a collaboration between Womanity and Behanbox.]

All the stories in the series can be read here.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.