Why TV News Is Getting Away With Irresponsible And Dangerous Conflict Reporting

Television media became disinformation outlets with their alarmist and incorrect reporting on the India-Pakistan escalations. Arbitrary enforcement of laws and ineffective self-regulatory bodies contribute to this crisis of credibility

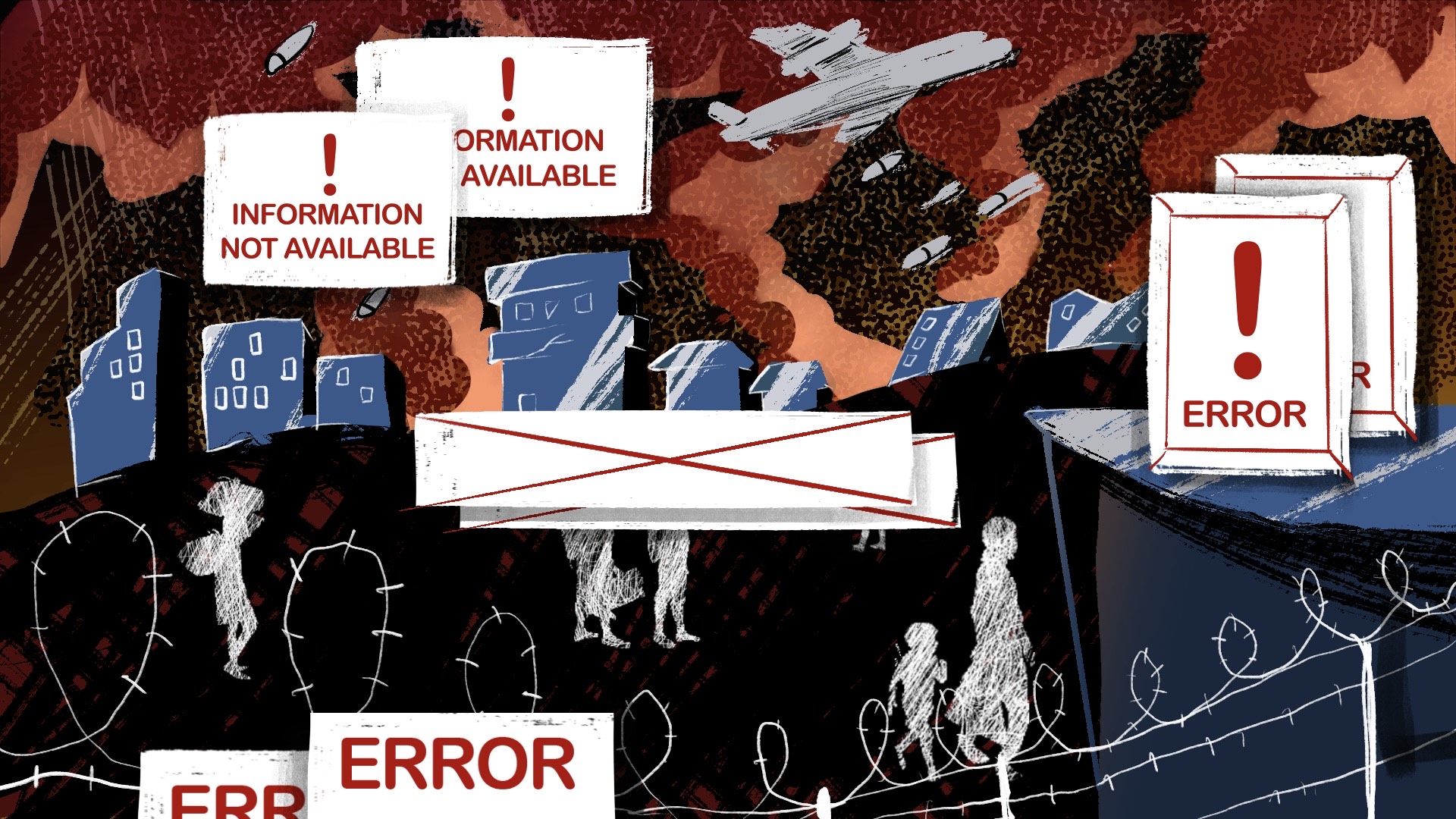

Between May 7 and 11, two kinds of warfare were on display: one of military power as armies exchanged drones, artillery, and shells across the India-Pakistan borders and another, of narratives. The latter was manufactured in part by television studios that showed incorrect footage, quoted “unnamed officials”, reported on events that never happened, and declared the enemy “defeated” more than once.

This production of fake news and fear mongering happened at an unprecedented scale, it has raised questions about the regulations governing the television industry and the government’s seeming reluctance to shut down fabricated narratives. As we explain, the crisis is enabled by arbitrary or biased enforcement of the law and the absence of independent regulatory bodies.

The broadcast of television news is regulated under the Cable Television Network (Regulation) Act, 1995, and attached rules, which warn media houses against live reporting of military operations and reporting based on “unnamed sources”. The television industry is also self-regulated through independent bodies with individual codes of conduct but have no legal muscle. As we explain later, neither managed to check the stream of falsehoods that turned television, the main source of news consumption in India, into a disinformation machine.

Prime time news reported confidently and erroneously, among other things, the “capture” of Karachi port and a strike on a Pakistani nuclear base that caused “radiation leaks”. Channels threw the nation into panic, stirred up jingoism, and undertook an “extraordinary exercise to mislead people”, says Geeta Seshu, a media scholar with Free Speech Collective, a coalition of journalists and activists.

The history of conflict reporting on Indian television since the Kargil War in 1999 is riddled with both promise and problems. TV news moulds people’s perception of the conflict and according to one report, boosted troop morale, but the medium has struggled with maintaining credibility and has been accused of turning war into entertainment.

“The very same problems occurred then [during Kargil] and occur now,” says Geeta. “There is an attempt to obfuscate, to hide, and to distract. When this media puts out a huge amount of disinformation and is allowed to do so without checks, then one needs to start asking questions, not just of the media, but also of the government.”

‘An Extraordinary Case’

Half-truths, lies, misinformation, and AI-generated content are a “staple” of any crisis, Tal Hagin, a researcher for online watchdog FakeReporter, told the New York Times. Barkha Dutta’s live commentary for NDTV during the secret Tiger Hill operation in 1999 gave away military locations, wrote General VP Malik in his book Kargil: From Surprise to Victory. Live reporting by news channels during the Mumbai terror attacks in 2008 reproduced the same errors. It prompted India’s News Broadcasters Association, a self-regulatory body, to come up with a set of guidelines for covering armed conflicts and communal violence.

But this time was different. “It wasn’t that one or two television channels – the rogue ones, the errant black sheep – were airing false narratives. It was everyone, and it happened at an incredible scale,” Geeta says. India Today, Aaj Tak, News18, and others aired reports about Pakistani jets being shot down – visuals that were later fact-checked to be of Israel’s air defence system in action.

In a video posted on YouTube, senior television journalist with India Today Rajdeep Sardesai said that 24-hour-news channels sometimes fell into the trap of falsehoods engineered by the “right-wing disinformation machine under the guise of national interest”. Aaj Tak’s Anjana Om Kashyap said they were misled by AI deep fakes and social media, and had a glut of reports to verify.

It is not that the government has not moved swiftly to take down content before (here and here). “[So] How was this night-long picnic of televised mayhem allowed to happen?” Geeta notes. The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting has yet to act against channels that published incorrect news or violated the programme code but it did order X to block over 8,000 accounts, including those of reputed journalists and of media outlets like The Wire and Maktoob Media reporting on the conflict’s impact on the residents of border districts. These orders, under section 69A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 and Information Technology (intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics code) Rules, 2021, were issued against those “working against national interests”, the ministry told a parliamentary committee this month.

Australian journalist Phillip Knightley in his book The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist, and Myth-Maker noted truth is the first casualty in a war. Geeta points to how unregulated and lopsided coverage became a safety hazard that imperilled people’s access to verified news and created panic and fanned communal sentiments. Few outlets discussed the real tragedies of conflict.

Poor Enforcement, Partisan Action

The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting’s advisory on April 25 warned media outlets against undertaking any real-time coverage, dissemination of visuals, or reporting based on “sources-based” information. These would count as violations of the law and “previous unrestricted coverage had unintended adverse consequences on national interests”, it said. On May 9, the Ministry of Home Affairs asked media channels to refrain from using air raid sirens in their telecast, other than for community awareness.

But an advisory is not binding and only “it is an acknowledgement that the news coverage itself falls within the ambit of regulatory action”, says Apar Gupta, co-founder of the Internet Freedom Foundation.

The key legislation here is the Cable Television Network (Regulation) Act, 1995, and Cable Television Networks (Amendment) Rules, 2021. Rule 6(1)(p) restricts media programmes from carrying “live coverage of any anti-terrorist operation by security forces” and to only air “periodic briefing by an officer designated by the appropriate Government, till such operation concludes”.

In 1995, the law came on the heels of India’s economic reforms – the broadcasting industry had been liberalised and satellite television introduced. So far monopolised by the state-owned Doordarshan, cable television was opened up at the height of the Gulf War to private players and international channels like CNN and Star TV Network. Members of the then Ministry of Information and Broadcasting condemned the availability of foreign channels as “cultural pollution” and “satellite invasion”, and pushed for a regulation that prevents the transmission of content against “national interest”.

The subsequent Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act in 1995 mandated operators to register with an authority and comply with programme codes. In a landmark directive in the same year, the Supreme Court said that airwaves are public property, they should be used for public benefit, and sought a separate body to monitor this content.

That wars could be brought into people’s living rooms was first realised with CNN’s broadcast depicting live visuals from Baghdad (this later came to be known as the ‘CNN Effect’, the idea that 24-hour live news coverage can change political outcomes). Zee News and Star News followed, and their live coverage in 1999 made the Kargil conflict India’s first televised war.

Apar is of the view that the law has a sound scaffolding but is lacking in integrity: the regulation gives “tremendous power to the government” in how it is interpreted and enforced. The programme code uses terms like “hateful”, “false”, “anti national”, “national security”, “good taste”, or “decency” that are not clearly defined. “What is good taste and decency will be subjective. The subjectivity is inherent to its enforcement process,” Apar says.

Between 2006 and 2016, channels were blacked out at least 28 times coverage that flouted guidelines on airing adult content, nudity, or national security, per this analysis by Hindustan Times. Al Jazeera received a five-day penalty for showing a wrong map of India in 2015; it issued show-cause notices to three channels when their coverage of convict Yakub Menon’s execution was deemed to be “inappropriate” and anti-national; Malayalam news channel MediaOne was banned for two days in 2020 for its “provocative” coverage of Delhi riots. (This was challenged and reversed in courts.)

The code on national security violation was used for the first time in 2016 when NDTV Hindi revealed “strategically-sensitive” details about the Pathankot airbase during a militant attack, per an Inter-Ministerial committee. Journalists and activists criticised the decision to take the channel off air for one day.

Currently, an Electronic Media Monitoring Cell under the I&B ministry oversees content of more than 600 channels. Any violation is first reported to the self-regulatory bodies so that it can adjudicate between the body and members. But if unresolved, matters are escalated to an Inter-Ministerial Committee, which has the authority to cancel the channel’s license or prohibit its transmissions if there are more than three violations.

The government body comprises officials including joint secretaries home, defence, I&B, health and family welfare, consumer affairs, law and justice, external affairs, women and child development and representative of the Advertising Standards Council of India.

Apar calls the government oversight a “historical defect in the design of the enforcement of this regulation” because the committee is controlled directly by bureaucrats who report to ministers of the ruling party, which could affect their autonomy. The law, when exercised, is done with a degree of partiality, he says – voices critical of the government are penalised while corporate-owned mainstream media are let off the hook. “It is not that the powers are lacking. It is the improper exercise of the existing law, and arbitrary (in)action which violates the rule of law,” he says.

Crisis of Self Regulation

The television industry is largely self-regulated, unlike print media which has a statutory body (the Press Council of India) and unlike digital media that comes under the ambit of the IT Act.

Over the years efforts have been made to regulate the television industry. In 1998, for instance, the then-Information Minister Sushma Swaraj said a law was needed to put curbs on depiction of sex and violence, and also transmissions from Pakistan, to protect “traditional Indian values”.

The Bharatiya Janata Party-led government in 1998 pushed for a broadcast bill, which was first proposed by the United Front Government in 1997. The proposal gathered dust for decades until the MIB introduced a Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill in 2023 to contend with the digitisation in the broadcasting sector and pushed to create an umbrella regulatory framework for both traditional and digital platforms. Digital creators, academics, and activists called it a “censorship tool”, and others noted that it failed to lay out precise and particular programme codes for television channels.

In this vacuum, self-regulatory bodies – such as the News Broadcasters and Digital Association and the News Broadcasters Federations – have taken on the task of monitoring television news channels but observers say these are ill-equipped to deal with an increasingly fragmented media industry.

For one, there is no singular code acceptable to all television broadcasters. The NBDA’s code of ethics, as listed on its page, restricts channels from broadcasting information that “endangers people’s lives or encourages secessionist groups and interests”. There is no uniform code on conflict reporting outside of this. They issued one advisory during the India-Pakistan conflict, asking channels to refrain from inviting panellists and commentators from Pakistan so as to not undermine the “sovereignty, integrity, and security of the nation”.

The fine for any violation is a nominal sum of Rs 1 lakh and the channel is required to air an apology. The Supreme Court, while rebuking the “berserk” coverage of actor Sushant Singh Rajput’s death in 2023, called this regulation mechanism and penalty “ineffective”.

Another reason is that the enforcement of codes and oversight is the responsibility of the News Broadcasting Standards Authority, an entity led by a retired Supreme Court judge. Grievance redressal is done through an opaque process and members of the public are not included in the discussions. The website houses an online complaint form and a record of previous grievances; a review of recently dismissed complaints show concerns about channels broadcasting content in favour of the ruling BJP and for “blatant political partisanship”.

Unique Nature of War Reporting

The Kargil conflict coincided with a revolution in electronic media and created awareness about how conflicts are fought and turned deaths from statistics to human interest stories, noted scholar Dwaipayan Bose in this 2011 Reuters study. This may have even helped India gain an edge in the conflict by boosting the morale of the forces, according to the Pakistan Army’s Green Book. At the same time, reporting on India-Pakistan conflicts has been shaped by a “narrow nationalism” and belligerence, Bose noted.

War reporting is often enmeshed in government propaganda because the media is dependent on the defense spokesperson and establishment for information, Geeta says. Analysts praised the measured and timely press briefings during Operation Sindoor, but she points out the government was not as forthcoming with its responses or information on the loss of Rafale jets or the specifics of terrorists killed.

There is also a fundamental conflict at the core of this exercise: in television, war becomes a means to garner maximum TRPs while catering to public interest. Media viewership historically peaks during any kind of crises – wars, epidemics, disasters – and there’s money to be made. For instance, in 1999, Aaj Tak’s viewership grew from 1,619,659 on June 5 to 1,952,000 on June 26; with similar upward trends for Star News English and Hindi channels in that period, per the Television Audience Measurement ratings. In the 1950s – when fears of nuclear testing were at its peak and the Cold War loomed ahead – American broadcasterXX Edward Murrow expressed concern that television was being used to “distract, delude, amuse, and insulate”, and commercial interests were overriding editorial decisions.

Between March 2 and 8, 2019, the week following the Balakot airstrike, Aaj Tak and ABP News beat the most-watched entertainment channel (Star Plus) in weekly viewership numbers, per BARC data accessed by Newslaundry.

Former additional director general of the BSF Sanjay Sood wrote in The India Cable that with TRP wars, Operation Sindoor’s “entertainment value was undeniable”.

A Network for Women in Media India study found that “toxic and hegemonic masculinity” – anger, dominance, and sexism – was evident across 31 TV channels in 2021. This was an assessment made during peace times. “This toxic masculinity and war reporting sort of create a double explosive package”, Geeta says.

A Media Council

To Apar, self-regulation is not the answer for a modern media landscape where circulation and publication relies on large media corporations – the argument is for the government to do less, not more. “The blurring boundary between journalism and content needs to be regulated in a digital ecology through a modern form of regulation, rather than through a government regulatory body… We need an independent, autonomous authority which is not housed within a government ministry, and we can think about these kinds of bodies and how to make them.”

The demand for an autonomous media council has been around for almost a decade now: in 2011 the then chairman of the Press Council of India Markandey Katju had argued that television and radio need to be brought within the scope of the Press Council of India or a similar regulatory body. A parliamentary committee in March this year recommended setting up an umbrella body that coordinates and implements laws governing print, television, and digital media, and include representatives from the media, media unions, and independent public persons. Journalist unions, however, flagged the absence of media voices in this discussion, adding that the intent seemed to be pushing for more government regulation.

But there are questions to be asked here: Who should speak for a fragmented media industry? Will there be rules to govern those who can speak? And most importantly, will this media council imitate the Press Council, largely ineffective, according to Geeta, because it is headed by a retired Supreme Court judge and only has powers to censure.

Monitoring and self-regulation also cannot be left to the industry alone, and informed citizens need to be made a part of the process, Geeta notes. “We expect the public to actually give feedback to the media to do better – that is not there,” she says, adding that this absence will lead to a cycle where more unregulated, harmful content will appear on the airwaves and trust in the media sinks. The Reuters Institute Digital News Report warned what follows: people will avoid the news because of “toxic” and depressing content, consume information from unverified sources, and limit their political participation. As journalist Prem Panicker writes “we need regulators to leash this madness” but also “viewers to stop clapping for clowns”.

The human rights groups, Council of Europe and Article 19, in 2013 came up with a set of measures to aid independent broadcasting regulatory measures, one of which was: “The regulatory body should not be part of or affiliated to any ministry or other government institution. Its independence should be explicitly guaranteed by law and, if possible, also in the constitution.” The United Kingdom has the Ofcom which regulates television, radio, and on-demand services – and its mandate is enforced through the Ofcam Broadcasting Code prescribed in the law. Australia set up a statutory body regulating television and radio as early as 1992.

Geeta says even if these are imperfect solutions, they would allow for vibrant discussions and an attempt to review existing codes. “Countries across the world are struggling with this…but the manner in which the Indian television media went haywire was absolutely extraordinary. There is really no parallel across the world,” she says.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.