Why The Forest Rights Act Does Little For Adivasi Dwellers In Urban Jungles

Our cities were once forests, home to indigenous communities. In 2006, the Forest Rights Act was passed to undo the historic injustices against Adivasi communities but in cities, complex legalities get in the way of their fight for their homes

- Shreya Raman

It was a hot and sweltering day in late April but 72-year-old Parvati Mahale stayed put under a blue tarpaulin outside the Thane collectorate office. Just a week ago, two bulldozers had demolished her 5-bedroom house with all its belongings still inside.

Parvati mourns not just her home and the land it stood on but also the trees that went with them. “I had a lot of empty space in my 5 guntha (over 5,000 square feet) land where I had drumstick, mango, amla and ramphal trees. They uprooted all of them with those bulldozers and grabbed the land,” she said.

For the last 16 days, Parvati and other Adivasi residents of Thane’s Chirag Nagar have been on a hunger strike outside the collectorate demanding justice and ownership rights over the land for which they have been paying non-agricultural land taxes since 1952.

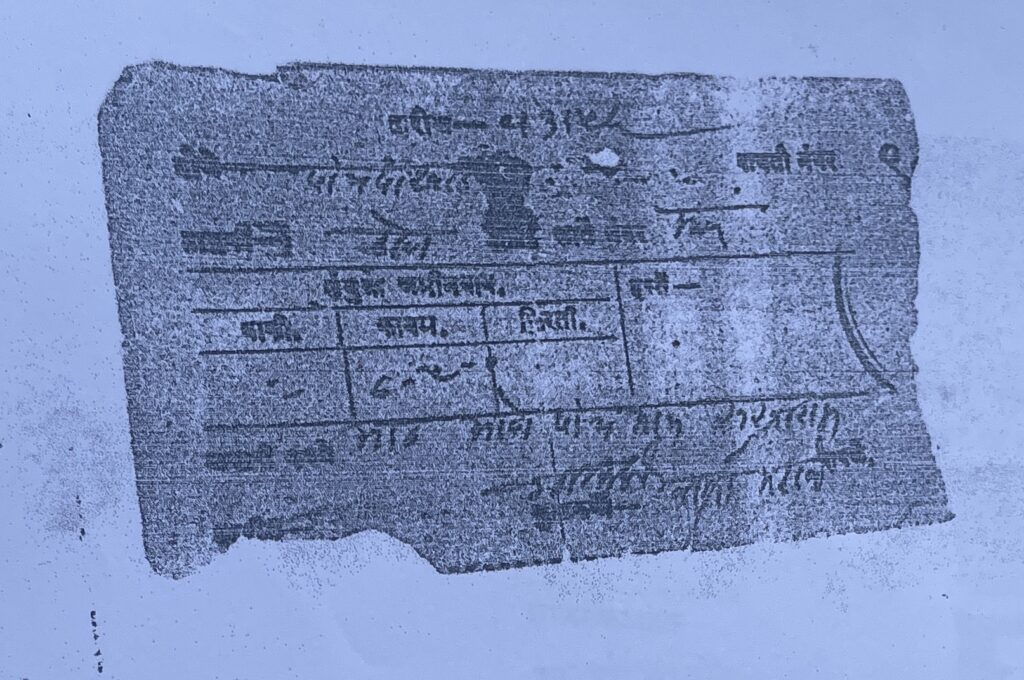

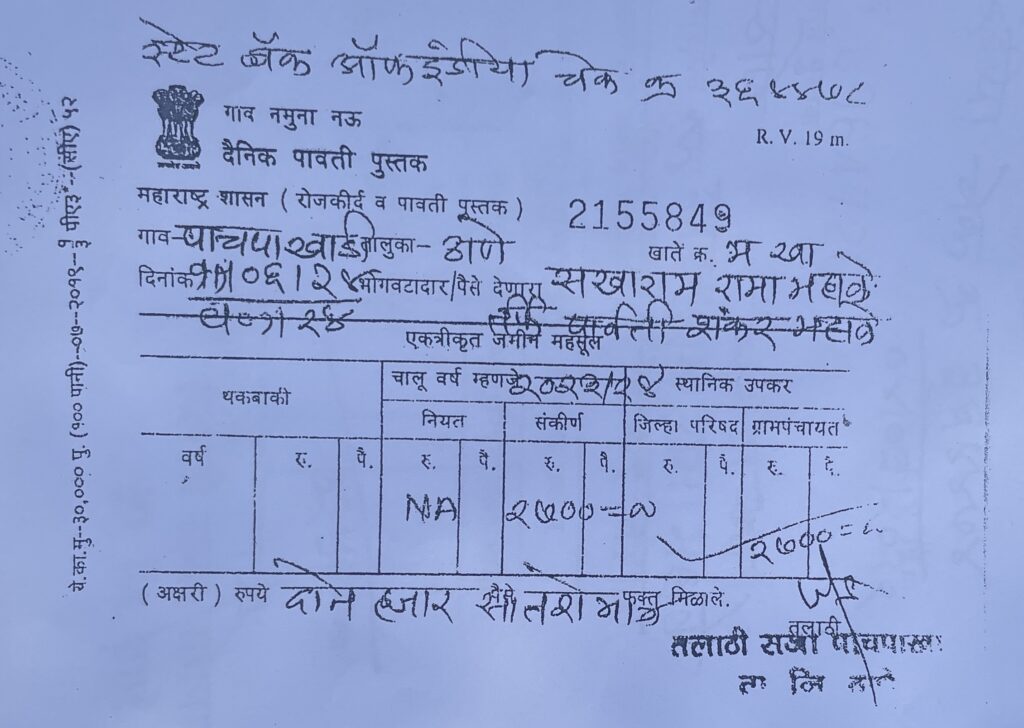

Parvati and her family have been living there for five generations. “My grandmother-in-law died here right before my eyes,” she recalled. “She told me that they used to live deeper in the forest but left [for forested areas closer to the city] because of the atrocities of the British. In 1949, the government declared this grazing land and gave it to us [without the titles]. In 1952, they did a survey and gave us receipts for non-agricultural tax. Since then we have been paying annual tax–from 50 paise to over Rs 2,000 now.”

In the decades after Independence, the 22 families that were given demarcated land and had been paying these taxes, tried to get the land transferred to their own names. In Maharashtra, the ‘7/12 extract’ from the land register [so named because it consists of information from two village forms bearing those numbers, specifying the details of land ownership and the type of land] maintained by the revenue department is the evidence of land ownership. The residents say that in 2007, the collector had told the Human Rights Commission that their names would be added in the extract but it has still not been done.

In the meanwhile, as the city developed, more people started living in the area, which turned into a slum with over 2,000 hutments. In 2016, the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, a statutory body created after the 1995 amendment to the Maharashtra Slum Areas Act, declared the land and area around it as “Slum Rehabilitation Area”. Five years later, the land transferred from gurcharan (grazing land) to state government property. But it was only in 2023 that the residents discovered these changes. The land had by then been transferred to a private builder for a housing project under the slum rehabilitation scheme. The state government has continued to collect taxes all the while.

The builders offered all the residents in Chirag Nagar a deposit amount of Rs 50,000, a monthly rent of Rs 12,000 and once the building was completed, a 1-bedroom flat of around 300 square feet.

“They ask us why we are not leaving when others have,” said 64-year-old Bharati Mahale. “Others had come here to fill their stomachs and were living in 10×10 feet rooms. So they accepted the deal and went. But we are indigenous to this land. We had bigger tin-roofed houses with 4-5 rooms, where we lived as joint families. How can all of us live in a single 300-square-feet house?” asked 50-year-old Sarita Photade.

On April 21, some of the residents got an eviction notice under sections 33 and 38 of the Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance and Redevelopment) Act, 1971. And within 24 hours, at around 1:30 pm on April 22, SRA authorities, the builder’s staff and police came with the bulldozers and demolished all the houses in the area.

“We asked for two hours’ time to move our belongings but they did not even give us that. They destroyed everything,” said Madhuri Sutar, 43. “They even cut off our gas connection and access to water, toilets and shut down medical dispensaries. They have now built a gate that is manned by security guards. We have to request them now whenever we have to go in or out.”

Ever since the demolition, the Adivasi families have been living on the rubble where their homes once stood. In the sweltering May heat, children are falling sick and are developing rashes. “The heat becomes unbearable soon after 7-8 am and the intensity increases through the afternoon. And once the sun sets, the mosquitoes start attacking us,” said Madhuri.

After 16 days of protests, on May 13, the collector met the protestors. “He told us what he had told us before–to just accept the builder’s offer. But why should we? We are fighting for our land,” said Madhuri, adding that their protest will go on.

Bharati pointed to the government’s dishonesty in continuing to collect taxes from the families even after the land had been moved to a private owner without informing them.

The crux of the problem here is rooted in a legal grey area around the rights of Adivasi communities—the applicability and implementation of forest rights in urban areas. In 2006, the Forest Rights Act was passed with an aim to undo the historic injustice faced by India’s indigenous Adivasi people. But the act’s rural-centric definitions and provisions have alienated similar rights for communities that now live in urban areas.

When Forests Became Cities

Parvati clearly remembers how different the area around Chirag Nagar used to be. “It was all covered in trees and our houses were scattered in the area. We used to walk as far as Kopar (around 8 km away) to get cow dung to make the houses,” she said.

Sarita remembered that when she was a child, there was no electricity or water in the area. “When I was small, around 8 years old, I used to walk 2-3 km to Vartak Nagar and Shastri Nagar to get water in my pots,” she said.

But over time, as the city developed, land use patterns changed and more people settled in the area. One of the key moments in the city’s growth was in 1961, when the first industrial estate in Maharashtra was set up in Thane. By 1982, the Thane Municipal Corporation was established and by 1990, almost 8 lakh people lived in the city.

Over 25 years to 2020, the built-up area in Thane city increased by 25.5%, while open area and forests have declined by 29.5% and 8% respectively. By 2050, the built-up area will increase by another 22.4% while open space and forest area will decrease by 37.6% and 9.8% respectively.

“As the city became bigger, more people came and they built houses in the empty areas. And then a Shiv Sena politician built a chawl and over time more and more people settled in the area,” said Sarita. And what used to be an Adivasi settlement became a slum.

A similar crisis is brewing in Mumbai’s Aarey forest. Since Independence, over 34 projects have fragmented the 3,200 acre lush and dense forest that act as a buffer for the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. The biggest among these were the Aarey Milk Colony in 1948 spread over 1,300 acres and the 520-acre Dadasaheb Phalke Chitranagari or Film City, incorporated in 1977.

As these projects came up, the Adivasi residents of the area started getting displaced and those who stayed faced routine harassment. Yashoda Varthe, 55, was born in Aarey’s Jivachapada. “When I was small, it was all a forest and there were only two Adivasis houses in the area,” she said. “We used to feel scared to go anywhere after six pm. There would not even be a cycle around.”

The real change came in 1984 after Royal Palms was built right next-door, she said. Spread over 240 acres, Royal Palms is a luxury mixed-development zone with around 2500 apartments, villas and bungalows and a similar number of commercial units. Yashoda said: “It was earlier created as a golf course and I worked there every now and then, clearing forest and collecting other waste. But, the rapid increase in population happened only later when it became an office space and residential area.”

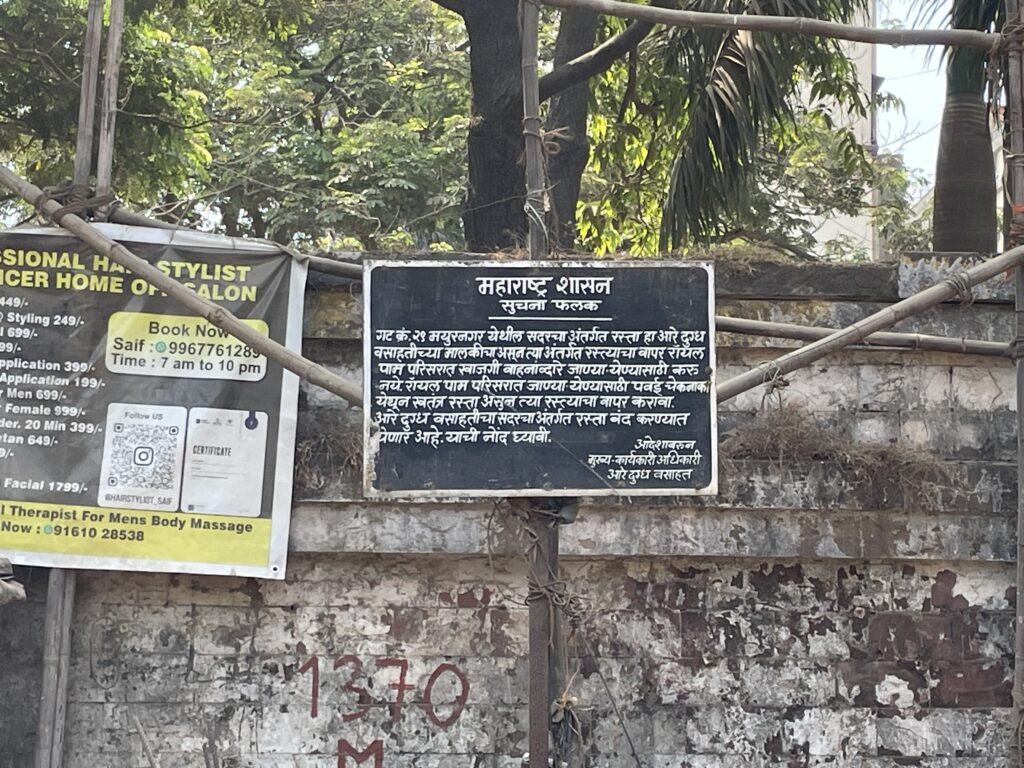

Less than 500 metres away from Yashoda’s house is one of the gates to enter Royal Palms. There is a Maharashtra government board outside the gate banning those entering or exiting Royal Palms from using the road leading to it because it stands on Aarey Dairy land. But people ignore the board. “The other gate is far for people coming from Goregaon or Malad. So they continue to use this gate,” said Yashoda’s son Nandu Varthe. Outside the gate is a bustling market and the area is now also called Mayur Nagar.

The story is similar in many other padas in Aarey. In February 2024, we had reported how the proposed Goregaon-Mulund Link Road was threatening the homes of Adivasi people from Habalepada. Shobha Dawda, 60, had told us then of how they used to live where the Film City stands now. The residents also spoke of routine harassment from Film City security personnel, including having to show ID cards to enter the Film City gate to reach their homes.

Morachapada, another hamlet that neighbours Royal Palms, has developed into a slum, said Nandu, adding that it has become difficult to know how many of the residents are Adivasis. “Many builders have tried to take that land to make buildings under the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme but it has not happened yet,” said Nandu.

‘Rewarding Developers In The Guise Of Welfare’

The genesis of the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme was in 1995, when the first Shiv Sena-BJP alliance government came into power in the state. The idea came from a contractor friend of Balasaheb Thackeray who suggested providing slum dwellers free pucca accommodation in a corner of the plot they occupy in exchange for releasing the rest of the plot for luxury construction. And soon, the Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance and Redevelopment) Act, 1971 was amended to provide for the creation of Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SHA).

What was initially touted to be a win-win situation, soon turned out to be a sour deal for the slum dwellers. Over four reports published on Scroll.in in 2024, civil engineer and urban planner Shirish Patel elaborated how the scheme has become a way to grab land while converting horizontal slums into vertical ones.

“Under the pretence of working for the welfare of the slum residents, the real objective is to reward developers,” he wrote. Given that the land value can be more than 10 times the cost of construction, selling the luxury parts of the development brings builders big profits, while slum dwellers get houses that have virtually the same conditions as their original homes.

These flats usually just about meet the minimum threshold of 300 square feet set by the government. They lack sunlight, ventilation and have poor sanitation facilities, water supply and other necessary amenities. “Half the conditions that define a slum remain unchanged, and after reconstruction nothing can be done about them for at least another century or so,” wrote Shirish, adding how this results in a large chunk of Mumbai’s population living in slum-like conditions forever.

In Aarey’s forests, politicians and builders are promoting the development of slums to take advantage of the SRA policies, said Amrita Bhattacharjee, one of the founding members of the Aarey Conservation Group. “Because then they get the land for free and that too in a prime location in the city,” she said.

And once slums start forming around Adivasi settlements, the community members are also considered slum dwellers and are forced into the small SRA flats. This is what happened in Prajapur Pada, said Amrita. In 2017, houses of 61 families in the hamlet were demolished by the Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation Limited (MMRCL) after referring to it as Sariput Nagar, an informal non-Adivasi settlement next to the pada.

The residents filed a petition in Bombay High Court challenging the corporation’s classification of Adivasi padas as slums. The petition said that the MMRCL “had deliberately overlooked and disregarded ‘Prajapur pada’ and started using the name of the location as ‘Sariput Nagar’ to treat tribal members of Prajapur pada as ‘slum dwellers’.”

“It took a year to fight and prove in the court that the petitioners are tribals and not slum dwellers,” said Amrita.

For 37-year-old Vandana Umbersade, the Prajapur pada was her home. “We had a huge house with an open porch that led to another covered porch, which led to a hall, kitchen and bedrooms. The road was far away and the pathway was filled with trees. We had a flower garden and sugarcane fields. They took it all away and instead gave us a 225 square feet flat without any bedroom,” she said, adding, “My mother cried for three months. It felt like we were put in jail.”

Vandana’s house was destroyed in 2005 for widening the Jogeshwari-Vikhroli Link Road. “They demolished half of the house the day before my wedding. We held the ceremony in a partly-standing house,” she said.

The Fight For Forest Rights

For the most part of pre-colonial India, Adivasi communities governed themselves outside the influence of rulers. But after 1793, as the British established their colonial rule, they introduced the zamindari system giving control of vast areas of land, including Adivasi territories, to feudal lords for the purpose of revenue collection.

The Land Acquisition Act of 1894 made way for colonial invasion of Adivasi territories, which intensified in the post-colonial period in the form of development projects such as dams, mining, industries, roads and protected areas.

In May 2002, an environment ministry directive led to one of the most brutal eviction drives of Adivasi people, sparking massive protests ahead of the 2004 general elections.

In October that year, Maharashtra became the first state in the country to issue an order recognising land rights in forests. This order became the model for the central government’s November 2005 order on recognition of rights and also the draft of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, commonly called the Forest Rights Act, which was passed in 2006.

The act, in its preamble, recognises the historical injustice meted out to Adivasi communities and made way for recognition of individual and community forest rights and established the right of the communities to collect non-timber forest produce. One of the key provisions of the act is that it made Gram Sabha consent mandatory for diversion of forests, providing communities with the rights to self-govern their forests.

It provided such legal protection for communities living in village forests, state forests and protected areas. But soon after the act was implemented, Adivasis and other forest dwelling communities from multiple states pointed out that the forest that they had rights over were in urban areas, said Tushar Dash, an independent researcher.

But neither FRA nor the Panchayats (Extension To The Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA) of 1996—another act that aims to enable tribal self-governance—are applicable in urban areas, creating a legal vacuum.

And this vacuum has also been used by governments to bypass PESA. In Andhra Pradesh, the government tried to extend the ambit of the Visakhapatnam Metropolitan Development Authority (VMRDA) to some portions of the notified Scheduled Areas through an executive order. In Chhattisgarh, the government proposed “upgrading” three gram panchayats to form a nagar panchayat, which would preclude those villages from the purview of PESA.

“The matter [of forest rights for communities in urban areas] was first taken up in the Bombay High Court and after the court intervention, there was a discussion in the ministry of tribal affairs. In 2015, the ministry issued a guideline extending the scope of FRA to forest areas in urban areas,” said Tushar.

Exerting Rights In Urban Areas

The first community forest rights in an urban area was recognised only in 2021. In Chhattisgarh’s Dhamtari district, tribal communities living in three wards of Nagari Nagar Panchayat were given community rights over 10,200 acres of forest.

“Earlier the forest department would stop us from collecting forest produce and firewood but now after we have got the rights, it has become easier and we are now able to protect our forests collectively,” said Saraswati Dhruv, a member of the Forest Rights Committee in Nagari.

In Aarey too, the communities have been trying to get their individual and community rights recognised. In view of rapid development inside Aarey colony, the residents of the 27 padas filed claims in 2019.

In October 2020, 300 hectares of land in Aarey was declared as a reserve forest. Since then, a Forest Rights Committee consisting of representatives from 27 padas was formed. Both Nandu and Vandana are members of this committee.

While both asserted that any project that will come in the area will need the consent of the committee, it is another legal grey area. Under FRA, the committee is only meant to assist the Gram Sabha in processing and verifying rights claims.

“We have only had meetings to discuss the Goregaon-Mulund Link Road project and the electricity line that Adani wants to build. We are yet to discuss issues of forest rights,” said Vandana.

While the 2015 guideline became a stepping stone to recognition of the rights of urban Adivasi people, getting those rights realised has become like navigating a complex puzzle. The guideline empowered Wards Committee to be the urban version of Gram Sabha, while the rest of the process stays the same.

This is inadequate because it does not tackle the unique challenges that come up in urban areas.

“I work on the land rights of tribal communities in Aarey and I am taking the help of people who are working in rural areas where decades ago the implementation of FRA started. And as we are discussing, we are realising that the issue in rural areas and cities are very different,” said Amrita.

One of these challenges is the overlapping of various laws like the SRA and the Maharashtra Regional and Town Planning Act of 1966 under which the Planning Authority creates a development plan for an area. The authority also has the power to evict any unauthorised construction or encroachment. “There is no clarity on which act takes precedence over others in case of an overlap,” said Amrita.

Another problem is that Adivasis form a very small part of the urban population, which means that Ward Committees end up having a majority of non-forest dwellers, contradicting the spirit of FRA.

And then there are situations like the Thane one where it is not about claim over forest land but a fight over rights to land that was bequeathed to a community decades ago which existing land records show no proof of.

“There has been no effort by the state to identify the communities who are living in urban areas, where they have got rights, and explore how the 2015 guideline can be used by these communities,” said Tushar. This has meant many communities continue to have problems in accessing these rights in urban areas.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.