A Permanent Home, Promised Over 10 Years Ago, Remains A Dream For This Delhi Basti

The crises faced by Kathputli Colony’s families, displaced by an interminable redevelopment project, point to the capital city’s struggle to provide affordable housing

For the last eight years, Sarojni Bhat, 46, and her family of five have been living in a cramped 12×8-sq ft house with fiberglass walls in a transit camp in Anand Parbat in west Delhi. She says the doors of the structure are rickety, there are cracks on the walls and seepage is a perennial problem.

These ramshackle units were supposed to be only temporary accommodation for Sarojini and 2800 families of the city’s migrant puppeteer community. In 2014, the homes of 4000 of these families were razed in the redevelopment of west Delhi’s Kathputli Colony, a sprawling basti for puppeteers, musicians, magicians and acrobats.

Many families were moved to the Anand Parbat transit camp, 5km from their old homes, on the promise that they would be allotted “improved housing” – 30 sq-ft flats – within two years in the new buildings that were to come up in their own colony. But it is now well over a decade and the displaced have no idea when they will be given pucca homes.

“Years later, we’re still trapped in these broken shelters.” says Sarojini, frustration etched on her face.

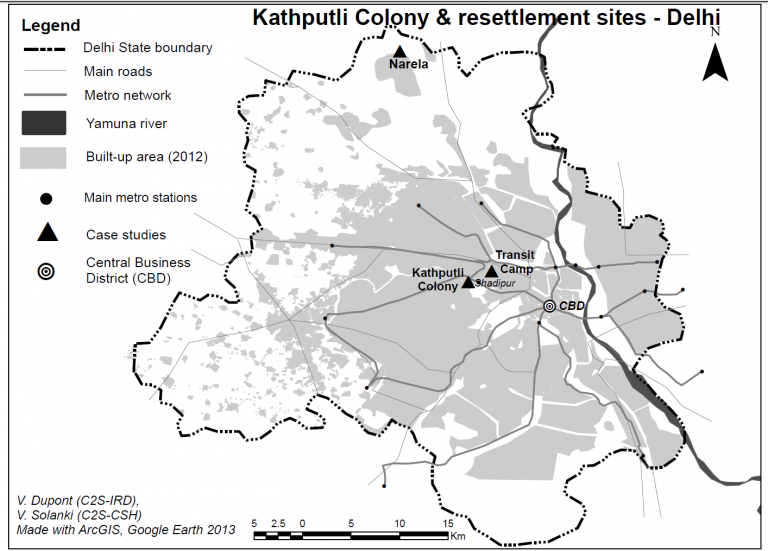

The other displaced families were scattered across various parts of Delhi. Some were rehabilitated in Anand Parbat, others in far-flung Narela. And these were the lucky ones. As many as 771 families—nearly 20% of those displaced— were left to fend for themselves, moving to rental accommodations, seeking out other bastis, and grappling with homelessness.

The displacement has not only forced families to settle for substandard homes, it has also hit their livelihood opportunities. There was a time when Kathputli Colony was a known address for performers and patrons knew where to go but now that the artistes are scattered, the community has lost its cohesiveness.

Puran Bhatt, an acclaimed puppeteer, was one of the first settlers of the Shadipur Depot land parcel. The colony had begun in the 1950s as a cluster of tents housing Rajasthan’s itinerant puppeteers in an open field then on the outer edges of the city. Bhatt speaks of the toll of displacement: “We have lost our craft to this resettlement. Earlier, a family of puppeteers would have at least 3-4 shows a day. Now, getting that much work in a month is difficult.”

The community network has been disrupted too, he says. “When we were invited to perform puppetry, we’d recommend friends—magicians, snake charmers—to join the show. Now, no one knows where we live. People don’t know where the puppeteers, magicians, or snake charmers are. Delhi lost us, and we’ve lost work,” he says.

The demolition of Kathputli Colony marked a turning point in Delhi’s urban redevelopment narrative, aligning with the Master Plan for Delhi 2021. It was the first-ever in-situ slum rehabilitation project for Delhi, in collaboration with Raheja Developers, undertaken by the city’s housing body, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). This alternative appeared to be better than being resettled in distant colonies, as we reported earlier in Behanbox.

But a combination of factors – delayed construction timelines, lack of coordination between the DDA and Raheja Developers, and inadequate provisions for temporary housing—have left thousands of families living in subpar conditions, show our interviews with residents and urban housing experts. The project has run into protracted delays and bureaucratic apathy. DDA officials say they are unaware of the project’s construction status, and cannot offer confirmed dates for its completion.

The slum redevelopment model, first introduced in Mumbai in 1995, is now facing criticism, particularly with the Adani Group’s planned redevelopment of Dharavi. The project threatens to displace at least 65,000 families, sparking widespread protests and raising concerns about land grabbing at the expense of long term residents.

Housing the urban poor is a challenge many Indian cities are struggling with. According to the 2012 estimate by the Technical Group on Urban Housing Shortage , approximately 19 million (18.78 million) households faced housing shortages in urban India. By 2018, this figure had risen to 29.2 million, marking a staggering 54% increase in just six years.

‘Our Basti Was Better’

The Kathputli Colony redevelopment project had been implemented through a tripartite agreement between the DDA, slum dwellers, and Raheja Developers, which stated that “around two years will be required to construct flats”.

Raheja Developers was to provide rehabilitation housing on one-third of the total land parcel in the Kathputli Colony; the remaining land was to be allocated for commercial use. This included the proposed construction of Raheja Phoenix, touted as “Delhi’s first true skyscraper”, and still incomplete.

The camp was well-maintained during the initial occupancy by the first batch of families, old timers recall. But, ten years later, following the arrival of the final batch of settlers, the prefabricated structures and infrastructure — evacuation pipes, concealed drains, cemented alleyways, platforms and so forth — began to deteriorate. The combined effects of overcrowding, insufficient basic services, and poorly maintained public toilets have recreated slum-like conditions.

“It was much better back in our basti. Here, we’re trapped for life,” says a resident.

At the camp, access to basic necessities is a struggle. Tap water is available only for an hour a day, says Sarojni. On each street 19–40 houses are dependent on a single water tap connection, turning water collection into a daily ordeal.

The housing units lack kitchens – there is only a bare cubicle where families cook – or private toilets, forcing residents to rely on shared bathing facilities and a single toilet at the end of each lane. These shared amenities are poorly maintained and often lack running water.

Transportation is another expense. Kathputli Colony had been located on the main road where rickshaws and auto-rickshaws were easily available. It was close to the Shadipur bus depot and metro station. In contrast, the camp is located on an out-of-the-way hillock, and bad transport facilities and dependence on electric rickshaws to reach the main road are general complaints.

Increased commute costs further forced many families to pause their children’s education, especially girls’, we learned.

The camp residents, still tied to their old address on ration cards, remain administratively linked to the fair-price shop near their demolished settlement. This forces them to make frequent trips for basic rations, with the burden of these journeys often falling on women. Kamo, a resident, shared, “I usually walk to the ration shop and only take an e-rickshaw on the way back. Those Rs 10 saved can buy tomatoes for a week. I’d rather walk.”

Although Raheja Developers are responsible for maintenance, repairs are temporary and need multiple complaints. Abdul Shakeel of Basti Suraksha Manch, a platform for residents, points out that the transit camps were meant to last 2–4 years. “How much longer can they hold up after a decade?” he asks.

Loss Of Traditional Livelihood

The loss of livelihoods was one of the biggest blows for the families in the transit camp, say those we interviewed. The relocation disrupted the work of the puppeteers and performers living in the once-vibrant Kathputli Colony.

“Earlier, we were always busy making kathputlis at home. Now, there’s no demand, and only a few of us still follow our craft,” says Patasi, who is something of a community leader. “We never had to think twice before buying essentials, but now even securing two meals a day is a challenge.”

Some of the displaced people, unable to secure work, have moved into rental accommodations or shelters for the homeless,” says Shakeel.

Govinda, a waste picker in his late 20s, along with his family, was also displaced from the basti and lived in the transit camp briefly. But he later moved to a shelter home near Britannia Chowk in North-west. He recalls that he could not make ends meet in the transit camp. There was no space there for waste segregation work and every time he put out even one sack of waste, DDA officials would demand that it be removed immediately. “Collecting waste around neighbouring Moti Nagar or Shadipur costs us ₹40–₹50 in travel alone. If all our earnings go to travel, what will we feed our children?” he says.

Govinda is not sure he can work out of a flat after he is allotted one.

Govinda, like many others in the transit camp, has been forced to face the reality of his situation. Now, he and his family live and work in the areas surrounding Britannia Chowk as waste pickers. They return to the transit camp only on Saturdays and Tuesdays to sell nimbu-mirchi, a charm made from lemon and green chillies.

Stuck In Narela

Between 2014 and 2017, the DDA’s eviction drive displaced over 4,000 families from Kathputli Colony, scattering them across various parts of Delhi. The project applied two cut-off dates based on arrival in the original settlement, leading to differential treatment among residents.

Households with proof of residence before 2011 qualified for two-room flats in the in-situ rehousing complex and temporary accommodation in the transit camp. Those with proof of residence between 2011 and January 1, 2015, were eligible for direct allotment of flats in Narela, on Delhi’s northern outskirts, under a DDA housing scheme. However, families unable to prove residence before 2015 or establish themselves as distinct households were deemed ineligible for any alternative housing.

As many as 492 families were relocated to EWS (economically weaker sections) flats built by DDA in Narela. Located nearly 35 km from Kathputli Colony, and perched on the city’s outer periphery, this area offers little in terms of connectivity or opportunities. With one DTC bus terminal, the closest metro station– Jahangirpuri on the Yellow Line, is around 19 km away, taking anywhere from 30 to 50 minutes to reach.

Kulsum Bhat, 56, who once worked as a magician alongside her husband, says the couple lost all work after they moved. “My husband passed away in the first year after we moved. Now we rarely get gigs, and then too mostly at birthday parties where my son goes with a friend on his bike,” she says. “The money we earn barely covers the travel costs, but we can’t just sit idle.”

Devi, who had lived in Kathputli Colony for 35 years before its demolition in late 2017, complains of being isolated in Narela. “There are hardly any people here apart from us. There are no jobs nearby; my sons have to travel over 20 km to find work. We feel neglected and confined here,” she says.

Those accustomed to living in close-knit bastis find the isolation of Narela’s high-rise slums intimidating. “The officials won’t even let us cook on a chulha outside,” says Devi. “They say, ‘We didn’t give you these buildings to burn chulhas out in the open.’ But how else do we cook when we can’t afford a gas cylinder?”

Residents also complain of rising crimes and say they feel unsafe on Narela’s roads after sunset.

Along with Rohini and Dwarka, in 1987, DDA envisioned Narela as Delhi’s third affordable mega sub-city under the Urban Extension Project. But while Rohini and Dwarka thrive as self-contained settlements balancing urban and suburban living, Narela has struggled to attract residents and remains largely a ghost town because of its inadequate infrastructure.

Residents relocated from Kathputli Colony to Narela remain uncertain about the permanence of their housing. While some families have adjusted to their new surroundings, others worry about potential eviction, as DDA has yet to release the final list of beneficiaries.

Senior DDA officials clarify that the flats in Narela have not been given to the residents of the now-razed Kathputli Colony permanently. “Of these beneficiaries, if some are eligible for a home under the project and want to continue living in Narela, they will be permitted. However, if they are ineligible, they will have to vacate,” says an official who did not wish to be named.

DDA’s Retreat From Affordable Housing

The problems with the Kathputli Colony redevelopment project expose its lack of commitment to the poor, says Dunu Roy, director of Hazard Centre, an organisation focussed on the daily perils faced by communities and labor groups. “DDA was envisioned to acquire land and build housing to address the needs of a rapidly expanding migrant hub like Delhi. Yet, the housing crisis persists because DDA has failed to fulfill this responsibility,” he says.

The DDA has acquired most of the land it planned to under its original mandate but has largely retreated from its core responsibility of building affordable housing, repurposing large tracts for commercial activities, says Roy. “In the last 60 years, the DDA has constructed about 11 lakh houses; the target was closer to 70 lakh. That’s less than 10% of what was planned,” he says. Of these 11 lakh units, the majority cater to middle-income groups and High-income groups.

To address its shortcomings, the DDA has shifted focus to public-private partnerships (PPP) for in-situ redevelopment projects, such as the one at Kathputli Colony. “Relying on the private sector, which is driven by profit motives rather than public interest, to achieve this objective is fundamentally contradictory,” argues Roy. “In the case of Kathputli Colony, Raheja Developers and the DDA retained two-thirds of the land, underscoring how land developed by the poor is often expropriated.”

Indu Prakash, an activist and member of the Supreme court’s State Level Shelter Monitoring Committee says that the DDA’s flawed functioning under successive Lieutenant Governors – it is overseen by the Ministry of Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs – have forced people to fend for themselves. “Residents have relied on makeshift housing, incrementally built over time using whatever resources they could gather from their urban experiences,” he observes.

Only 23.7% of Delhi’s population resides in what are officially classified as “planned” colonies, with the majority living in unauthorised colonies, jhuggi clusters, regularised-unauthorised colonies, and resettlement colonies. As urbanist Gautam Bhan asks: “What could be a greater indictment of planning than nearly 75% of the city living in housing that is apparently ‘unplanned’?”

Excessive Reliance On In-Situ Model

The Master Plan for Delhi-2021 (MPD), implemented by DDA, projected a requirement of 24 lakh new housing units, with 54% designated for economically weaker sections and lower income groups. Of these, approximately 42%, or about 10 lakh units, were planned to be delivered through densification and redevelopment of existing residential areas, including in-situ slum rehabilitation, infill development, and redevelopment of unauthorised colonies.

However, the pace of housing development for the urban poor has been excruciatingly slow. The Kathputli Colony redevelopment project, the first initiative under the Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY), faced significant delays. Even with the introduction of the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), which emphasises in-situ slum redevelopment through its slogan of “Jahan Jhuggi, Wahan Makaan“, progress has been sluggish.

While the DDA failed to complete the Kathputli Colony project, it managed to deliver housing to 3,024 slum-dwelling families from the Bhoomihen Camp, with these units inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2022 at Kalkaji. Additionally, this month, ahead of the upcoming Delhi elections, housing allocations have been made to 1,400 families in Jailorwala Bagh, Ashok Vihar.

But housing units provided under the in-situ slum redevelopment component fall drastically short of the needs of Delhi’s estimated slum population, conservatively pegged at 15.5 lakh. And the condition of allocated high rise housing units of the poor, such as those in Kalkaji, highlights critical issues, including unsanitary conditions, inadequate water supply, and lack of security.

As per Shalaka Chauhan, an urban researcher and coordinator of the people’s campaign Mai Bhi Dilli for Delhi’s 2041 Master Plan, the capital city relies too heavily on the in-situ slum rehabilitation model. The plan estimates a need for 34 lakh housing units by 2041 but does not specify clearly how the units will be divided as per affordability.

Chauhan also highlights the limited success of schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), which benefited only 2.5% of urban beneficiaries. “Its success depends on ideal conditions—prime land, appropriate density, and community consent—rarely found in Delhi’s jhuggi clusters,” she says. “The plan’s over-reliance on this model, without exploring alternatives like slum upgradation or community-led solutions, is a significant limitation.”

Reimagining Housing For The Poor

When asked what she expects from the upcoming elections, Sarojni’s response is straightforward: “All we want is to get the promised flats as soon as possible, so we can finally get out of this gutter.” Her immediate concerns weren’t about better water supply or improved roads in her colony but securing long-awaited land titles.

However, the question remains: can state elections solve the housing needs of those like Sarojni, when its primary public housing authority is centrally controlled?

DDA oversees land pooling, planning, and housing development, while the state government plays a key role in implementation, regulation, and addressing local housing needs. Says Chauhan: “the state government’s direct responsibilities include slum rehabilitation, the allotment of government housing units, and affordable housing schemes such as in-situ redevelopment. Hence the state must engage with communities, ensure transparency in rehabilitation processes, and secure consent from residents—key elements often missing in centrally managed projects.”

Roy says that the state government should go beyond building or regularising colonies to “reimagine housing delivery” and taking responsibility for making living conditions habitable, “particularly through models like slum upgradation”.

To acknowledge informal housing as an essential part of the urban fabric, rather than dismissing it as ‘illegal,’ is to affirm the right of inhabitants to shape the city, says Shalaka. This not only enables the state to address the housing crisis but also legitimise the lived practices through which people contribute to the production of urban space, she adds.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.