How Delhi’s Governance Is Hobbled By Bewildering Battles For Turf

Who do you hold accountable for Delhi’s governance? Is it the AAP-led state government, the BJP-led central government that commands the Delhi Police, Delhi Development Authority and National Highways Authority of India, or the locally governed Municipal Corporations of Delhi?

There is no one answer. The National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi as a hybrid of Union Territory and State has seen friction between central, state, local and over 100 para-statal bodies since its creation in the 1990s. Delhi has struggled to share its sovereignty with the Centre, while also grasping its own autonomy and this battle has played out between political parties and in courts.

Various stakeholders have acknowledged the complexities of multiple centres of power and overlapping authorities that often make it difficult to identify and fix accountability for citizen services such as healthcare, power or law and order. Among world capitals, the administration in Delhi is “by far the most convoluted” and has given way to an “undeniable governance chaos” as its population soars, wrote policy expert Niranjan Sahoo. Delhi’s “complicated” and “overlapping jurisdictions” as a capital city, political contentions, and subsequent legal interventions have shaped the Delhi model of governance.

As almost 1.5 crore voters head to vote in a high-stakes three-way contest in the Vidhan Sabha elections on February 5, we explain how political and administrative power is divided in Delhi, and the history of this mish-mash style of governance.

Triple Layer of Governance

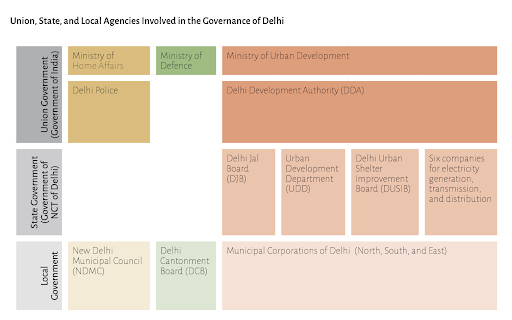

Governance in Delhi happens across three levels – the Central Government, the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi (GNCTD), and local governments including the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD). The citizens of Delhi elect seven Members of Parliament during the Lok Sabha elections, 250 councillors to the MCD during city elections, and 70 members of the Legislative Assembly during the Vidhan Sabha elections. The last assembly elections were held in 2020, with AAP winning an absolute majority with 62 seats.

The GNCTD is governed through the rules of a legislation passed in 1992 through an amendment that we explain later). As in other states, the GNCTD which is governed by the Legislative Assembly is responsible for overseeing basic services such as transport, power generation, food and civil supplies, health and family welfare, industrial development, and revenue administration. Different agencies, such as the Delhi Jal Board and Urban Development Department, operate under the supervision of the Chief Minister and Council of Ministers.

Outside the state government’s purview are law and order, urban planning, and land development. The 69th amendment to the Constitution in 1992 empowered the Central Government to retain full control over these ‘reserved subjects’ through an administrator, in this case, the Lieutenant Governor. The LG serves as the constitutional head of Delhi, is nominated by the Centre, and appointed by the President, and exercises control over all matters of land, police, and public order.

Elected members are not permitted to ask questions pertaining to these subjects in the Legislative Assembly unless allowed by the LG. Delhi Assembly speaker in 2023 argued in favour of abolishing the question hour entirely when some members raised the issue of corruption in the police or the DDA. “When the Speaker cannot accept questions about the Delhi Police, services, land and the building department, what subjects remain to be accepted?” he asked.

Earlier, the ruling AAP has pointed fingers at LG V.K. Saxena and the BJP government for “ruining” the city’s police force, high crime rate, and gang wars. In 2022, Delhi reported the highest rate of crime against women, as per the NCRB data.

The local government functions through five urban local bodies. The last three were created only in 2011, after the Legislative Assembly passed an amendment to the Delhi Municipal Corporation Act, 1957, which cleaved the singular MCD into three parts:

- New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC), covering an area of 42.7 sq km in and around Lutyens’ Delhi

- Delhi Cantonment Board (DCB) overseeing 43 sq km in South West Delhi

- North Delhi Municipal Corporation

- South Delhi Municipal Corporation

- East Delhi Municipal Corporation

These local bodies are accountable to multiple stakeholders. Per the 2011 amendment, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs appoints a commissioner to lead the trifurcated MCDs. It also assigns the Secretary of the Urban Development Department (under the GNCTD) as the Director of Local Bodies charged with coordinating work, resolving issues and framing rules around recruitment in civil posts.

“Due to multiple centers of power and the multiplicity of authorities, which in turn report to different departments and ministries, it is very difficult to identify and fix accountability for many of the civic services in the city,” noted a 2020 policy paper by Praja, an NGO working on accountable governance.

A civil servant from Delhi who requested anonymity told BehanBox there has been a “de-facto breakdown in the hierarchical structure” since 2015, when AAP defeated the BJP in assembly elections. The Government of National Capital Territory Act, 1991, takes ‘government’ to mean the government of Delhi, but since 2015 in practice, ‘government’ has meant the Ministry of Urban Development or Ministry of Home Affairs, the source says. “The chain of command is broken…If officials are taking orders from the Centre, and they are the ones responsible for your posting, you will be unresponsive to the Delhi Govt,” the source adds.

The electrocution-related deaths in the city’s unauthorised colonies and Old Delhi illustrate the problem. Between 2023 and 2024 itself, almost 50 instances of electrocution were reported during the monsoons due to loose wires. These resulted in the deaths of 26 people, including children. Violations of building by-laws and encroachments have worsened the situation. But it is hard to pinpoint the authority responsible for the mess – power distribution companies such as the Tata Power Delhi Distribution Limited or the BSES Rajdhani Power Ltd (a collaboration between the GNCTD and Reliance) do not have any authority over encroachments. The Ministry of Housing Urban Affairs in 2018 asked an array of government bodies including the DDA, MCD, Delhi Jal Board, Public Works Department, and more to keep a check.

These multiple checkpoints made corrective measures challenging, noted this 2019 report in the Indian Express.

Similar confusion has ensued on matters of growth and development, pressure points in a burgeoning city where more than one-third of the residents live in substandard and unsafe housing including unauthorised colonies. The centre-governed DDA makes master plans but their implementation depends on more than 10 other bodies who work independently of each other. For instance, the National Capital Regional Planning Board and National Institute of Urban Affairs are accountable to the Centre; the Public Works Department and Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board report to the state government; the four municipal corporations are responsible for actually implementing the master plans. This discordance “though appalling.. is actually representative of the city itself”, noted a study published in the Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health.

An Inherent Conflict

The drafting committee in 1950, including BR Ambedkar and Jawaharlal Nehru, argued against placing the national capital territory under the administration of a local government. In 1951, Delhi was classified as a Part C state under the Government of Part C States Act. Delhi would have an elected chief minister-led council of ministers and a chief commissioner with powers over “public utilities, sanitation, water supply” and more, but not over the police, public order, and land. The State Reorganisation Exercise in 1956 reclassified Delhi into a Union Territory to be governed by a LG, abolishing the state-level legislative power. The Municipal Corporation of Delhi and a limited local government (the Metropolitan Council) were established in 1958 and 1966 respectively, when Delhi had no Legislative Assembly. The city still lacked an accountable governance system fueling discontent among the citizens.

A growing demand for statehood culminated in special provisions for Delhi. Articles 239AA and 239AB were included through the Constitution (Sixty-Ninth Amendment) Act, 1991. This followed the recommendations of the Balakrishnan Committee in 1989, which supported Delhi’s identity as a UT but recommended incorporating a Legislative Assembly and Council of Members. The former would allow the Central Government “to discharge its national and international responsibilities” at the seat of power, while the latter would acknowledge the “legitimate demand” for people’s democratic right to participate at the city level. The amendment empowered the elected NCT of Delhi government to take decisions of matters under the State and Concurrent list, while the three subjects of land, public order, and police remained with the Centre.

Thus was created a Union Territory with state-like features. The Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi Act, 1991, was passed later to outline the powers of the Legislative Assembly and Council of Ministers. BJP’s Madan Lal Khurana, the region’s first Chief Minister, in 1993 likened the Delhi Assembly to a body without a soul, according to the book The Delhi Model by AAP leader Jasmine Shah.

The present contenders – the BJP, AAP, and Congress – have varyingly echoed demand for full statehood between 1991 and 2015. Delhi’s longest-serving chief minister Sheila Dikshit after her tenure rallied for full statehood, noting: “The city would have witnessed better development had my government not been shackled by the present governance structure of Delhi characterised by a multiplicity of agencies and authorities.”

Political tussle between the AAP and BJP since 2015, and subsequent legal interventions, have complicated governance. The latest NCT of Delhi (Amendment) Act, 2023, was passed after friction over who holds power over state public services and state public service commissions. The state has jurisdiction over the services but not its personnel – the people are picked from centrally administered cadres like the All India Service. The Supreme Court in its 2023 judgment noted the “triple chain of accountability”: voters elect representatives who formulate legislations and policies, civil servants implement said policies and are answerable to ministers, who in turn are answerable to voters. The chain breaks if the civil servants are not answerable to the elected Delhi government.

The recent amendment allows the Union Government to create the National Capital Civil Service Authority consisting of one representative from the Delhi government (Chief Minister) and two Union Government nominees (the Home Secretary of Delhi and Chief Secretary) to make recommendations on civil service matters such as transfers or postings. The LG holds discretionary powers in matters of conflict. . This had “the effect of reducing the importance of the elected government and Chief Minister”, noted this piece in The Hindu. Unlike other states which have an exclusive legislative domain in matters of healthcare or transport, the Constitution now gives Parliament powers to enact laws on matters that the Delhi Assembly has jurisdiction over.

Follow our Feminist Election Newsroom coverage here. You can find us on Instagram, WhatsApp, and X.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.