Despite Public Schemes,Vrindavan’s Widows Cannot Afford A Life Of Dignity

Pensions and access to healthcare schemes could have benefitted thousands of widows who settle in Vrindavan but isolation, apathy and red tape get in the way

- Anuj Behal

Bokul Dashree, 86, rechristened ‘Vaishnavi Dasi’ by her guru, has been living in Vrindavan for over four decades now. She left her home in Agartala 51 years ago when she was widowed at age 35. “Becoming a widow at such a young age was a source of shame for both myself and my family, so I felt the need to leave,” she says. Unsure of where to go, she left her children with her mother and set out for Vrindavan.

Bokul’s fascination with Vrindavan was inspired by popular devotional songs such as Brindaboner kunje ke bajay bashi, Radhar mone baje premer sur jeno hashi (who plays the flute in the groves of Vrindavan, In Radha’s heart, it resonates like a melody of love). She first arrived in Vrindavan with a relative and stayed for nine months. A few months later, she returned home to bring one of her sons. The son who stayed with her eventually moved back to Tripura after getting married.

For the past 30–32 years, she has been living alone in a rented room, paying Rs 1,500 a month. She can’t remember when she visited Tripura last or spoke to her son. Her daughter occasionally sends money or visits. But she mostly lives off charity, somehow navigating hardships. “I go to the Yogananda Trust for milk and vegetables on Sundays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. The Ramakrishna Mission provides rice, lentils, and oil once a month,” she says.

Bokul knows that the Uttar Pradesh government Women’s Welfare Department offers a pension of Rs 1000 under the UP Vridha Pension Yojana to everyone aged between 60 and 150 years living below poverty line. But she has long given up the hope of ever receiving it. “Five or six years ago, I applied for the pension through a ward councillor, but I never got it,” she says. “Where do I go? I don’t know who to ask and how to navigate the process.”

Bokul’s plight mirrors that of countless widows in Vrindavan. The UP government claims that 32,467 widows in Mathura district are registered as pension recipients. However, in conversations with over 30 widowed women in Vrindavan, BehanBox found that only nine (30%) received either an old-age or benefitted from the UP Government’s Widow Pension Scheme. Of these, only three women (10%) reported receiving a widow pension, while six (20%) mentioned receiving an old-age pension. This figure for widow pension falls even shorter than the findings of the 2010 UNIFEM report on multidimensional poverty, which states that only 25% of women receive a widow pension under any state or central pension scheme.

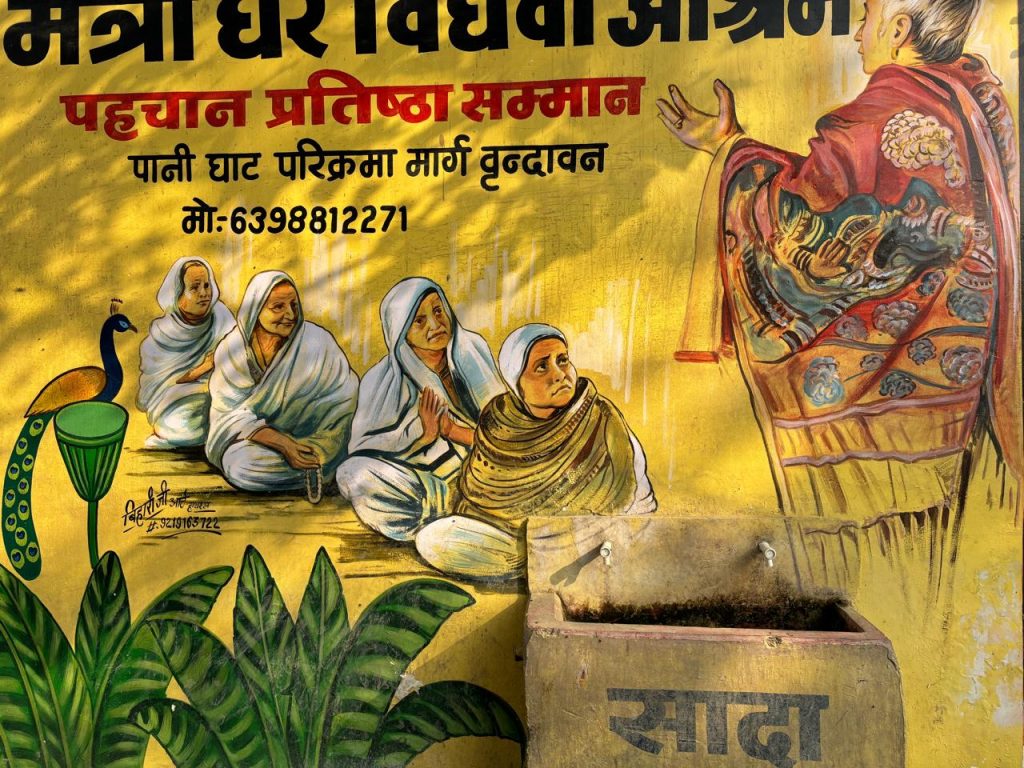

In Vrindavan, the experience of widowhood is shaped by both religious and social factors, and women come here in search of both spiritual solace and a sense of community. On the streets of Vrindavan, they are a visible presence, often in tattered white sarees, some stained with faint pink traces of gulal from Holi. They can be seen standing at street corners or at temples seeking alms.

Vrindavan is estimated to be home to more than 20,000 widows. While most come from West Bengal, others arrive from states like Tripura, Assam, Uttarakhand, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Chhattisgarh.

Widows in Vrindavan should ideally have access to a range of government welfare schemes, including pensions for the elderly and widows mentioned earlier, ration cards under the Public Distribution System (PDS), and they should also be covered by the Ayushman Bharat health coverage. However, our investigation revealed that bureaucratic red tape and a general lack of awareness about how to navigate these systems often prevent them from accessing these benefits.

Chanting For Rs 15

Jyoti Saxena runs the Om Vishranti Ashram in Vrindavan that houses nearly 70 destitute women. More than half these women do not receive any pension. “Ashrams like ours can barely sustain their operations and can only provide food, medications and shelter but cannot provide monetary support,” she says. “In such situations, women are often left to depend on families who usually don’t care about their whereabouts. So they resort to begging, survive on donations, or seek refuge in bhajan ashrams.”

Vrindavan’s bhajan ashrams are unique community spaces where destitute women gather to chant ‘Hare Krishna’ in exchange for small payments. At Bhagwan Bhajan Ashram, one of the town’s prominent centers, women convene twice daily—in the morning from 6am to 10 AM and in the afternoon from 3pm to 7 PM– to chant. At Rs 15 per session, Bokul can earn Rs 30 a day.

These centres are funded by devotees who also donate essential items like blankets, clothes, and food supplies. Bokul, who never misses a visit to the bhajan ashram, gestures toward her blanket and says: “I got this yesterday, along with Rs 500. But this kind of banta-banti doesn’t happen every day.”

Jyoti points to the fact that the widows have to sit and chant for hours to earn a paltry ‘fee’. “Why isn’t the government providing them with the necessary pensions?”

Hurdles in accessing pensions

Most widows do not know about the schemes they are entitled to. This and the inability to navigate red tape make it hard for the women to access their entitlement. For example, since arriving in Vrindavan, Bokul has not even received the rations she is entitled to under PDS. She holds a zero-balance bank account under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) to which her daughter occasionally adds some money.

Women who live on their own – without the support of an ashram system – have an even harder time. Of the nine women who reported receiving pensions during interviews, seven live in ashrams, and two rented homes – both have been in Vrindavan for over 40 years.

Last year, Krishna Dasi, 76, who moved from Nagpur to Vrindavan nearly a decade ago, managed to secure a ration card with the help of a local shopkeeper. It provides her with 10 kg of rice, 10 kg of flour, and half a kilo of pulses. “Before this, I depended on the bhajan ashram for survival,” she says. “I’ve heard that getting a pension is even harder than getting a ration card. I still don’t know where to go for it. I even visited the post office on someone’s suggestion, but it was a wasted effort.”

The lack of official identity documents is another hurdle. Lopa, 46, who migrated to Vrindavan after her husband’s death left her vulnerable to familial abuse, has given up all hopes of receiving a widow pension. “I went to the DM office in Mathura to apply, but I don’t have my husband’s death certificate,” she says. Under the UP Government’s Widow Pension Scheme, a husband’s death certificate and a Below Poverty Line (BPL) ration card are essential documents.

“How am I supposed to procure those certificates from home when my family only wants to harass me? Who remembers to pack such documents when they leave in a state of grief?” she asks.

‘No Dignity Without Some Money In Hand’

Gayatri Mukherjee, 69, moved to an ashram run by Maitri India in 2017 and has been trying to secure some pension since. The ashram does provide her with shelter, food, and medical care but having once worked in a hospital kitchen, she feels the lack of financial independence acutely.

“I feel helpless when I want to visit a distant temple, buy something specific to eat or wear, or even recharge my mobile. To be respected, one needs at least some money in hand,” she says.

Although Gayatri’s pension application has been processed through her ashram, there has been no progress on it. Initially, she tried to enroll in UP’s Widow Pension Scheme but was found she was ineligible, as the scheme only covers widows between the ages of 18 and 60. Undeterred, Gayatri pursued the Old Age Pension Scheme but was then told that the scheme is only available to those who have the documents, especially Aadhaar, to establish their residence in the state. This meant that she had to reapply for an Aadhaar card to update her address. This was done a few months ago but she has yet to get any money.

Migrant women without a permanent address in Uttar Pradesh struggle to meet the eligibility criteria under the UP old age pension scheme, especially if they cannot provide local proof of residence, such as an address linked to their Aadhaar card or voter ID. As a result, applying for an address change became a necessary step.

Vikas Chand, the District Probation Officer who oversees the pension scheme, says the District Magistrate’s Office has organised several sessions to facilitate pension applications and also digitised the process. But he acknowledged the challenges faced by widows who come from other states. “Since this is a state pension scheme, applicants must first change their address to a local one. Many times, the process is further delayed due to a lack of proper documentation,” he says.

Ghasita Ram, the manager at the Maitri Trust Ashram—whom everyone affectionately calls ‘Baba’—is currently struggling to help multiple women, like Gayatri, secure pensions. “The government is pushing us around, just like my name, ‘Ghasita’,” he quips. “There are many hurdles. The Aadhaar card should be from Vrindavan. Then they say there are network issues. And KYC issues keep delaying the process.”

Sometimes, he says, women are asked to go to the post office for the processing. There they are made to queue up for hours. “It’s difficult for older women,” he says.

Jyoti Saxena points to the fact that no one, not even the BJP MP from Mathura, Hema Malini has shown any inclination to help Vrindavan’s widows.” Hema Malini in 2014 made a controversial remark about the city’s widow population: “There are 40,000 widows in Vrindavan. If they come from Bengal, why don’t they stay in Bengal? There are nice temples there. Those who come from Bihar, why don’t they stay there? It will be a problem for Vrindavan residents.”

Sporadic Pension Payment

Kiran (Vrinda Dasi), 75, who has lived in Vrindavan for 40 years, had been receiving her pension regularly for many years until a few months ago. “I don’t even remember when I started getting the pension. I registered through my ashram,” she said. “But the last time I received a pension was in Phagun (March), when I got ₹4000. Since then, I’ve received nothing.” She visited the DM office in Mathura in May this year, where she was told that the pension would come in December.

Kiran has been surviving with the support of her ashram. At her age she finds it difficult to visit a bhajan ashram. She often ends up selling her PDS ration to a local shopkeeper to sustain herself.

Chand attributed the delays in pension payments to the recent implementation of the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme. “The shift to DBT ensures transparency by transferring pensions directly into accounts linked with Aadhaar cards. The delay is likely affecting women who are either unaware of the changes or do not have Aadhaar-linked accounts,” he explains. “We are addressing these concerns on priority and are actively guiding women on how to update their account details.”

A few other women mentioned receiving their pensions from their home states. Bhagwati (Yog Maya), who moved to Vrindavan five years ago, still collects her pension in Uttarakhand. “I go back every 4-5 months to collect it,” she says. She hasn’t tried transferring it to Uttar Pradesh where the pension of Rs 1,000 is Rs 500 less than what is paid in her home state. She has not transferred her ration card either for fear that it would impact her pension.

Pihariya, a tribal woman from Chhattisgarh, moved to Vrindavan a year ago impressed by the ‘Pookie Baba’ (Aniruddhacharya Maharaj), made famous by the internet. “I thought he could take care of me at this age. Maybe I wouldn’t have come here if I had a son of my own,” she says. The ashram takes care of all her needs so well, she says, that she does not feel the need to collect her pension from Chhattisgarh.

In contrast to pension, at least 14 of the 30 women we interviewed said they are receiving rations. According to a 2010 Report on the Poverty Levels of Widows in Vrindavan, there is little food-related poverty in the community because of an abundance of charity in Vrindavan and surrounding towns such as Barsana, Gokul, Goverdhan, and Radhakund. The study found that 72% of the widows ate three meals a day, while 25% ate twice a day. Their diet mainly consisted of staple Indian foods like rice, chapattis, dal, and vegetables.

Ayushman Card, The New Dream

On September 11, 2024, the expansion of the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PM-JAY) announced that all senior citizens aged 70 and above would receive health coverage, regardless of income. This includes free health insurance coverage of up to Rs 5 lakh per family. The scheme holds significant importance for widows in Vrindavan, as Ghasita Ram pointed out: “Even in the case of a health emergency, managing costs for elderly women is challenging for the ashrams. How can we arrange Rs 1-2 lakh every other day when most of the women suffer from acute health issues?”

However, none of the women mentioned being enrolled in the Ayushman Bharat scheme, nor had they even heard of it. Ghasita Ram emphasised the difficulty in enrolling women in the programme. The scheme requires that families be enrolled as a unit, but for women without families, the officials suggested to Ghasita, that 4-5 women be grouped as a ‘family.’ However, if one woman in the group receives benefits under the scheme, the others are left without coverage, as the scheme specifies per-family benefits.

The Supreme Court of India has issued several orders over the years addressing the conditions of widows in Vrindavan, particularly concerning their housing and welfare. One significant order came in 2017, when the Supreme Court directed the Uttar Pradesh government to address the poor living conditions of widows and improve the management of ashrams. This was part of a broader directive issued in response to a PIL filed by the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA), highlighting the neglect, exploitation, and lack of basic facilities for widows.

Reports, including those by the National Commission for Women (NCW), have highlighted that several ashrams in Vrindavan not only offer substandard living conditions but also hinder widows’ access to government benefits. Some of these ashrams have been accused of withholding critical documents, such as passbooks and identification cards, effectively preventing widows from directly availing pensions or welfare schemes. The apex court asked the government to ensure proper monitoring of ashrams and ordered the closure of those found mismanaged or unfit for habitation. These closures, though well-intentioned, led to a sudden displacement of many widows, as alternative housing arrangements were not adequately planned.

For instance, the Pagal Baba Ashram in Bhutgali, which is no longer government-run and now managed through private donations under Saxena’s Om Vishwanti Ashram Trust, exemplifies these challenges. Kiran, one of the widows, mentioned having to shift to rental accommodation following the sudden closure of Pagal Baba Ashram, only to return after it was acquired by Saxena’s trust.

Adding to this, Aniruddhacharya Maharaj’s growing popularity has attracted many destitute women to his ashram, despite his reputation for making highly controversial public statements that promote unscientific and sexist attitudes towards women. While many depend on his ashram for food, the capacity to accommodate is limited. The facility currently hosts around 300 women, and a new complex is coming up. Aniruddhacharya says that with donations he can ensure that the “mothers” at his ashram can survive without pensions or PDS.

Sumitra, 70, who has been left at the gates of the ashram by her grandson, is desperate to gain entry into the new facility. “Might as well wait here. If this doesn’t work out, where else will I go?” she asks, as she sits outside its gates in a makeshift arrangement.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.