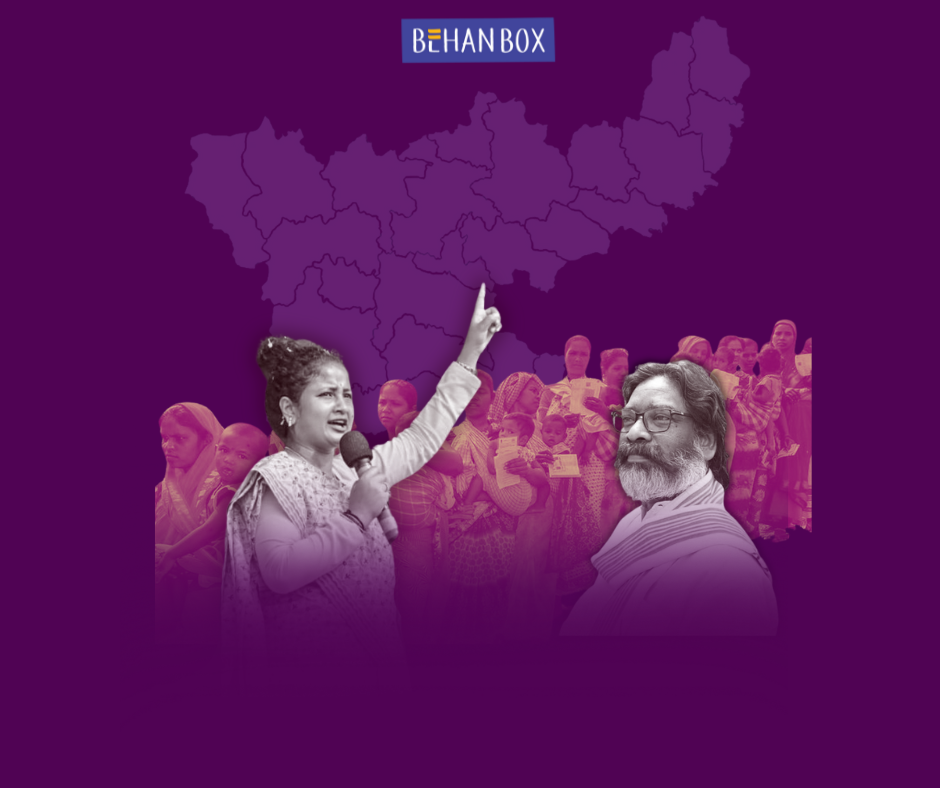

Maiya, Kalpana, and Mahila Mandals: How Women Shaped Jharkhand Assembly Elections

Women, especially from the Adivasi community, turned out to vote in record numbers and voted for the return of Hemant Soren’s JMM. We look at a slew of reasons that likely influenced their electoral participation and decision

- Garima Goel

It was the energetic campaign to engage with women voters through multiple initiatives that won Jharkhand Mukti Morcha’s Hemant Soren another tenure as chief minister of Jharkhand in the recently concluded assembly elections, show studies and interviews. While the most highly publicised of these was the cash transfer scheme, the Maiya Samman Yojana, political parties also attempted to mobilise women voters through community groups such as NGOs and SHGs, we found.

In what Soren called the toughest election of his life due to the pressure to deliver, JMM bagged 34 seats, with the Congress adding 16 seats, Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) four, and CPI(ML) two, giving the INDIA alliance 56 out of 81 seats in the assembly. The opposition NDA, led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was restricted to 24 seats. The BJP itself managed 21 seats, while its allies – All Jharkhand Students Union (AJSU), Janata Dal United (JDU) and Lok Janshakti Party (LJP-Ram Vilas) – contributed one seat each.

Analysts and commentators pointed to the role women played in Soren’s win. The overall turnout in Jharkhand stood 67.7%, with women voting in greater numbers (70.5%) than men (65.1%) in 68 out of 81 constituencies, as per Election Commission of India.

Additionally, data indicate that women not only turned out in higher numbers but also voted differently. According to a post-poll survey conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), there was a notable 7-point gap in female support between the two coalitions: 45% of women voted for INDIA, compared to 38% who backed NDA. And among women, it was rural and Adivasi women who provided significant support to INDIA: 48% of rural women supported INDIA, compared to 37% in urban areas, and INDIA received 60% of the votes from Adivasi women, as per the survey.

Similarly, an exit poll by AxisMyIndia, which closely predicted the actual seats, indicated a substantial gap in female vote share between INDIA (47%) and NDA (35%).

So what explains this high participation and the decisive vote of the female electorate?

Women were undoubtedly at the heart of election campaigns and voting in Jharkhand –every major party made a concerted effort to woo female voters through welfare schemes, targeted publicity material, organisational contact, and engagement with women’s groups. We look at how the Soren campaign managed to connect better with them.

Women in Campaigns

The elections were held against the backdrop of CM Soren’s arrest by the Enforcement Directorate on charges of corruption in January this year and subsequent release towards the end of June. During his time in jail, his wife Kalpana, who had previously refrained from participating in active politics, stepped in to rally support for her husband and the party in the run-up to the Lok Sabha elections held in May. She was also elected as MLA from Gandey in the assembly bypolls held alongside the Lok Sabha polls.

Since then, Kalpana has emerged as one of the INDIA bloc’s most prominent campaigners. In the month leading up to the first phase of the assembly elections, she conducted nearly 85 public meetings. A JMM campaign manager, speaking to Hindustan Times, admitted that there were more requests for her appearances than for the CM himself.

At a rally in Nagri block in rural Ranchi, women in the audience were visibly excited when Kalpana arrived. With a mic in her hand, without a podium or notes, she spoke in a simple yet aggressive tone that resonated with the crowd. She explained how nobody before Soren had thought of aadhi-aabadi, or the women of Jharkhand. With one hand raised, Kalpana asked: “Jharkhand ka mukhyamantri kaisa ho?” to which the crowd roared back: “Hemant Soren jaisa ho!” Throughout, she actively engaged the voters, ending her speech by coaxing people to tell her the polling date and raise their palms (the Congress symbol) for the candidate she was campaigning for.

One attendee I spoke to after the rally mentioned how Kalpana inspires her to speak boldly. Another woman, who wasn’t eligible to vote in the elections as her voter identity was registered in neighbouring Bihar, said that she had come to the rally “just to see Kalpana”.

While other parties lacked a crowd-puller like Kalpana Soren, they employed their own strategies to engage women voters. NDA partner AJSU, for instance, appointed a ‘chulha pramukh’ for every 10 households, aiming for at least half these positions to be held by women. Modelled on the BJP’s idea of panna pramukh (incharge for 10-12 households listed on a page of the electoral list), AJSU’s chulha pramukhs (literally ‘Hearth Chiefs’) were to engage with voters, especially women, at a micro level.

The BJP shaped its campaign around the theme ‘Roti, Beti, Maati’, and circulated a list of 10 Adivasi women in the Santhal Pargana zone who were allegedly victims of “Bangladeshi infiltration.” This claim was disproved in investigations by the civil society group Jharkhand Janadhikar Mahasabha and Scroll, the news website. Although the BJP sought to appeal to Adivasi women by claiming to be agitating for their protection, judging by the elections results – including in Santhal Pargana where the party managed to win only one out of 17 seats – it would appear that the women preferred welfarist politics to “protection”.

Women as Labharthis

The Hemant Soren-led Jharkhand government launched the Maiya Samman Yojana in August 2024, under which Rs. 1000 was promised to all women aged 18 and 50. The first tranche was disbursed in August itself and since then the scheme has been all anyone could talk about.

Women could be seen queuing outside Anganwadi centers, block offices, and common service centers to fill out forms for the scheme. Special camps were organised by the government to ensure that beneficiaries were reached. A common refrain among women was, “Maiya waala paisa mila kya (did you get the amount under Maiya Yojana)?”.

The Hemant Soren government also went to great lengths to publicise the scheme. Four installments were strategically disbursed ahead of elections, timed around popular local festivals – Rakshabandhan, Karma, Durga Puja, and Chhath – and framed as celebratory “gifts.” Jharkhand government advertisements via hoardings, digital ads, and pre-recorded phone calls ensured there was no confusion about the scheme’s origins and voters attributed it to the state government in general and to Hemant Soren in particular. Kalpana Soren conducted a state-wide tour, the Maiya Samman Yatra, emphasising to women that this was a “gift from their brother Hemant dada”.

Women, who received the benefit, were excited to have the new money in their hands. When asked how they were spending the money, their responses varied. A young Rajak (SC) woman said she donated the first installment to the local temple during Durga Puja, others said they recharged their phones or were supplementing their family income.

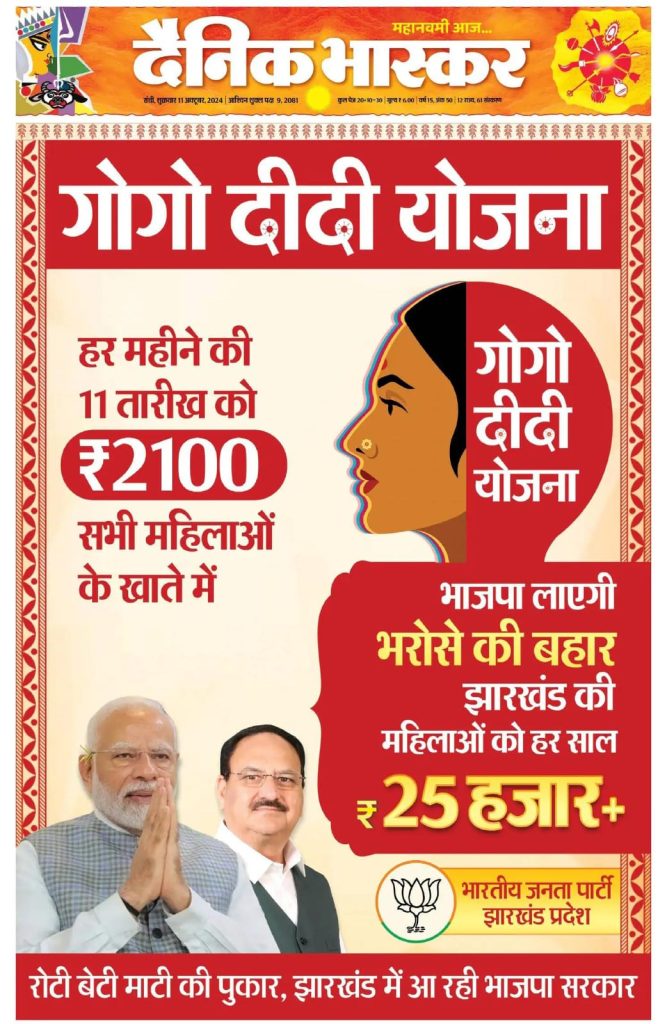

While the BJP criticised the scheme as an electoral gimmick, its potential impact was not lost on them. In its manifesto, the BJP promised a similar scheme, the Gogo Didi Yojana, offering Rs. 2100 to women, and even launched a campaign to collect beneficiary forms. In response, the Hemant Soren government announced in its last cabinet meeting before the model code of conduct came into effect that the amount under Maiya Samman Yojana would be increased to Rs. 2,500 starting December, if the JMM were re-elected.

Did these efforts actually help the INDIA alliance secure reelection? Survey data indicates they did. According to the CSDS post-poll survey, three in four respondents were aware of the Maiya Samman Yojana and two in three said women in their families had applied for it. Those who were aware or had applied showed a clear preference for the incumbent INDIA bloc over the NDA. A similar pattern was observed in the CSDS survey in Maharashtra. Here applicants of the government’s Ladki Bahin Yojana, which provided Rs. 1500 in cash transfers to women, showed a preference for the Mahayuti alliance.

The impact of these cash transfers is further evident in instances of negative voting in their name. For example, Nikita Tirkey, an Oraon Adivasi woman, working as a housekeeper in Ranchi and earning about Rs. 8000 per month, shared that she had not voted for Congress because she had not received the Maiya Samman amount.

Two other financial schemes were very popular among women: free electricity and a waiver of outstanding electricity bills. Effective August 2024, the Jharkhand government stopped billing households that consumed up to 200 units of electricity and also waived their old electricity dues. Women mentioned how both initiatives lead to household savings, particularly valuable during the current inflation.

The CSDS survey found the free electricity scheme to have the maximum reach among state government schemes, with a larger share of the scheme beneficiaries voting for the INDIA bloc (50%) than the NDA (34%).

Efforts to mobilise women voters, however, extended beyond these welfare schemes.

Women Mobilised via Women’s Groups

Across Jharkhand, numerous self-help groups (SHGs) have been formed by both state governments and private NGOs. Very often a village or a mohalla can have more than one group, with most women in the area attached to them. These groups regularly meet to save money and also organise to procure development goods.

When election season arrives, political parties in Jharkhand often tap into these ready-made networks, reaching out to women leaders and participants to not only secure votes but also to mobilise support on their behalf.

One such leader, Laxmi Kumari, took the task of mobilising on behalf of a political party ahead of elections. As a ‘vikasini’ (agent of development), she heads a 15-member community action group constituted by an NGO that works to organise urban women. The group runs a community toilet, sustaining it through small contributions from 40 households in the mohalla.

I accompanied Laxmi as she went door-to-door in her locality, reminding women to attend a political meeting that evening. The women, mostly from the Bhuiyan (SC) community, praised Laxmi for her help with pension applications, ration cards, and Aadhaar registrations, and assured her they would be at the meeting.

About 15 km away, Fulo Tirkey, another women’s group leader, had just finished distributing pamphlets on behalf of an incumbent BJP MLA seeking re-election. When asked if she had been approached by candidates from other parties or would consider campaigning for them, she quickly responded: “It wouldn’t be right to entertain others when the MLA has done so much for us.” She pointed to the paved road I had taken to reach her and the Sarna prayer spot we were meeting at, both projects made possible by the MLA’s intervention and funding.

Fulo, an Oraon Adivasi, laughed as she acknowledged that being part of the women’s group has boosted her confidence and given her a voice, and hoped that women in her mixed-caste locality would vote for the candidate she was campaigning for. The candidate was indeed one of the 21 BJP MLAs who won, and when I called her post-results she said: “As soon as we are done with the paddy harvesting season, we will meet him to congratulate and ask him to get started on our pending work.”

In Jharkhand it is widely acknowledged that AJSU founder Sudesh Mahto was a pioneer in leveraging women’s groups for electoral mobilisation as early as 2005. Mahto, a multiple-term MLA from Ranchi district’s Silli assembly constituency was unable to retain his seat this time. “His past victories can be credited to his smart use of women’s groups from panchayat level, regularly meeting and funding them,” said Anand Mohan, a senior bureau chief at Prabhat Khabar, a newspaper published from Ranchi.

Voting as Transaction

It is no secret that political parties fund women’s groups ahead of elections, expecting support in return. Even cash transfers schemes, such as Jharkhand’s Maiya Samman and Maharashtra’s Ladki Bahin, are often dismissed as “transactional”, with women seen to be supporting incumbent governments in exchange for money.

However, the women beneficiaries and self-help group members I encountered did not agree with this view. For them, the cash assistance and mobilising via women’s groups was also an acknowledgement of their socio-economic realities – low incomes, poor infrastructure, and the State’s inaccessibility once the elections ended.

In electoral politics, schemes and groups like these also enable political parties to reach a broader electorate, cutting across traditional caste lines. And data suggest that incumbent governments in both states were, to some degree, successful in doing so.

But the lesson for parties from the two recent elections shouldn’t be that women’s votes can always be swayed in this manner, said Vasavi Kiro, an activist and former member of the Jharkhand State Commission for Women.

“It is okay as a one-time economic empowerment measure. By turning out in such huge numbers and voting decisively women have made their presence felt. Now it’s time for governments to do more, to think about their genuine political and social empowerment,” Kiro added, hoping the new government will take steps such as appointing women to key positions and providing skilling opportunities for women in SHGs.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.