A Frog In A Well Seeing the Himalaya

What was it like for an Indian woman in the early 20th century to travel for pleasure? In this essay excerpted from Zubaan’s new book, Three Centuries of Travel Writing by Muslim Women, early Bengali feminist Begum Rokeya offers insights

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880–1932), better known as Begum Rokeya, was among the most influential of first- generation Bengali feminists. She is credited with a significant body of prose fiction, poetry, and essays and was also a known educationist. Born into a conservative zamindar family of what is now Bangladesh she was denied formal education. Married at 16 to a much older civil servant she however found a supportive figure in her husband. Most of her writing was in Bengali but her best known work ‘Sultana’s Dream’ (1905), a short story on a feminist utopia where men have to be in purdah and women run a country with advanced technology.

This travel article, “Kupamanduker Himalaydarshan” (A Frog in a Well Seeing the Himalaya), was one of a number of early articles published by Begum Rokeya in Calcutta-based journals in 1903–4. The first of a handful of travel accounts by the author, it describes a leisure trip to Kurseong in the eastern Himalaya with her husband. The article was published in Mahila (Lady), among the dozen Bengali women’s periodicals that appeared mostly from Calcutta in the colonial period.

It provides the reader with quite a different perspective on women’s, and particularly Muslim women’s, mobility in eastern India. And how difficult it was for even an upper-class woman to fulfil the dream of travel to a dream destination.

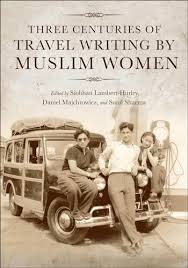

The travel essay is from Zubaan’s recent volume, Three Centuries of Travel Writing by Muslim Women, edited by Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Daniel Majchrowicz, and Sunil Sharma. ‘Women have long been so excluded from being considered serious travelers or travel writers that most readers will likely struggle to think of a single such figure from any historical or literary tradition,’ say the editors in their introduction to the book. They point out that ‘Muslim women travelers are rarely accorded even this limited recognition but are instead twice neglected: for being insufficiently masculine, and the Orientalist assumption that they belong to a religious or cultural background that demands meekness.’

The travel writings in this book spanning four centuries prove how wrong these assumptions are.

Now we are in the Himalayas. An old wish fulfilled: I have seen the mountains. The Himalayas may be nothing new for our female readers, but for me it was an entirely novel experience. My desire to see the Himalayas had been awakened by reading in books about its lakes, mountains, springs, and so on. With a silent sigh, I used to think that it would be impossible for me to see all that. What increased my pain was the thought that people from faraway Europe visit our Himalayas, but we do not get to see it! But finally, by the grace of God, we have also seen the Himalayas.

Traveling on time, we reached Siliguri Station. The Himalayan Rail Road starts from Siliguri. The eastern Bengal trains are smaller than the East India trains, and the Himalayan train is even smaller than the former. These small trains are as beautiful as toy trains. And the wagons are very low, so much so that the passengers, if they like, can effortlessly get on and off while the train is in motion.

Our train went upward very slowly, covering a long, winding path. The wag-ons made rumbling sounds as they loop south or north again. There were amaz-ing sights on both sides of the rails: in some places deep lowlands, in others extremely steep summits, and in yet others dense forests.

At times I saw refreshment rooms and stations. There was a ladies’ waiting room in almost all those places. The rooms were well furnished. Our European cotraveling sisters got off at most stations to take rest. In the waiting rooms, there were many vessels for washing one’s face, and four ladies could wash their hands and faces at the same time. Whether the ladies bring luggage with them or not, they most certainly have with them a comb, a brush, and powder. Bengali women do not manage to order their thick hair in such a short time! But however that may be, the diligence of the European sisters is most laudable. In the waiting rooms, there are ayahs from Bhutan.

Gradually we have come up to three thousand feet above sea level. There is no cold yet, but we have moved through the clouds! I suddenly began to mistake the clean white fog in the deep valley for a river. The trees, creepers, grass, and leaves—all are amazing. Such big grass I have never seen before. Even the green tea fields have enhanced the natural beauty a hundred times. The lines and rows of bushes look very beautiful from afar. The occasional narrow walking path look like a parting on the head of the earth! The dense, dark green woods are the thick hair of the earth, and the paths her bending part.

Many waterfalls or springs came into view while on the railroad. Their beauty is beyond description. They emerge from somewhere with incredible speed and disappear elsewhere, constantly splitting the stony heart of the snowy mountains. Who would believe that one of these is the source of the mighty Ganges? The train stopped by a large creek, and we thought it did so that we might behold the water stream to our hearts’ content. (In reality, however, the real reason was something else: the water was exchanged there.) But for whatever reason, the train stopped and our hearts’ desire was fulfilled.

Now we have ascended to four thousand feet. I don’t feel cold yet, but I was released from the terror of the heat that had by then almost exhausted our life-breath. A light wind was blowing smoothly. Here, at 4,120 feet’s height, is Maha-nadi Station. I couldn’t read the station’s name very well, but from what I saw it seems to be Mahanadi indeed. However, if the name of the station is erroneous, it is not my fault but that of the distance between my wagon and the station!

Finally we arrived at Kurseong Station, at a height of 4,864 feet. Upon seeing the crowd at the station, I sat down for a while in the ladies’ waiting room and watched the face-washing and hairdressing of the European sisters. One had a little boy with her. She ordered the ayah to wash his face and got on the train. The ayah cared little about making the boy wash his face. She wiped the boy’s face with the lady’s leftover towel and ran to the train approximately ten seconds later. This is what happens when you rely on servants. It became less crowded when the train left, so we left the waiting room.

Our place was not far from the station, so we got there quickly. Some of our trunks had erroneously been booked to Darjeeling. We arrived (before dark), but lacking our things, we couldn’t make ourselves quite at home. Our trunks came back with the evening train. Before we could go to Darjeeling ourselves, our belongings had succeeded in breathing in its air! From the very next day, we felt absolutely at home. Therefore I say that it isn’t enough to find refuge in order to feel at home; you also need the necessary furniture and equipment!

Here it hasn’t yet started to get cold, but it isn’t warm either. How about calling this the mountainous springtime? The sun rays are very sharp. Since we came, it has only once rained a little. The air is very healthy, though the water is reportedly not good. We filter our drinking water. But the water looks very clear and clean. There are no wells, nor rivers or ponds—it is genuine spring water. Look-ing at the pure cool water soothes the eyes, its touch soothes the hands, and the cool air or thick fog all around it soothe the heart!

The air here is clean and light. Watching the hide and seek of wind and cloud is fabulous! At one moment the cloud is on one side, then the wind comes from the other and drives the cloud away. Every day the setting sun creates a kingdom of amazing beauty with the wind and the clouds. Liquid gold is poured on the mountains in the western sky. Thereafter many youthful clouds smear gold on their bodies and start running from here to there with the wind. Looking at their spectacle, I pass my time; I lose myself and cannot do anything else.

I remember that I once read in Mahila magazine about [a particular type of] fern. I had taken this fern for some tiny shrub. It was only from a geology book that I had learned that in the carboniferous age, there were huge fern trees. Now I saw these fern trees with my own eyes. I was full of joy. I broke a branch and measured it to be twelve feet long. The whole tree would be twenty to twenty-five feet high.

In some places the woods are very dense. The good thing is that there are no tigers, so you can walk around without fear. We love it to stroll around on lonely, wild paths. There are snakes and leeches. So far we haven’t come across any snakes, and leeches have sucked our blood only two or three times.

The women of this place are not afraid of leeches. Bhalu, our servant from Bhutan, says: “What harm do leeches do? When they have sucked enough blood they go away by themselves.” The Bhutanese women wear a seven-yard-long piece of cloth like a skirt. Another piece of cloth is bound around the waist, which they top with a jacket and cover the head with a foreign shawl. They climb some stony, disheveled path with one or two maunds [i.e., roughly 37–74 kg] of load on their backs without hesitation, and walk down again the same way! With this weight they playfully walk up a path, the sight of which makes all our courage disappear!

The editor of the Mahila magazine once wrote about us that “the female sex is weak, therefore they are called abala, those without strength.” I ask whether these Bhutanese women are also a part of this weak sex. They do not depend on men for their food but earn it themselves. I even see more women than men carrying stones: the men don’t carry more than they do! The abalas, those without strength, carry stones away. The sabals, those with strength, spread the stones on the path to build streets, and both boys and girls join in this work.

So “those with strength” here seem to include both boys and girls. The Bhutanese women introduce themselves as paharni, or mountain women, and they call us niche ka admi, people from below. As if, in their opinion, the “people from below” were uncivilized! They are by nature diligent, fond of work, courageous, and sincere. But living in touch with the “people from below,” they are by and by losing their virtues. They learn faults like stealing little amounts of money in the market, mixing water into the milk, etc. They even marry “people from below”! In this way they are getting mixed with various peoples.

Many don’t understand how one can travel to different countries while ob-serving the purdah system ordained by the Muslim scriptures. So they feel in danger when they have to leave the house to go somewhere. The current pur-dah system is harsher even than the few strict rules concerning purdah in the scriptures! However, if you just obey the scriptures, you don’t face too many difficulties. In my view, the one who considers brothers and sisters the same is the true guardian of purdah.

Almost a mile away from our habitation flows a huge creek; one can see that water stream with its milky foam from here. Hearing the song of its waves day and night, the intensity of devotion to God flows twice or thrice as much. Why, I ask, doesn’t the heart too, like this creek, flow and fall below the feet of the highest Lord?

What else shall I say? Here in the mountains, I am extremely happy and grate-ful to God. I have seen a humble sample of the ocean, that is, the Bay of Bengal; what remained to be seen was a sample of the mountains. Now this wish has also been fulfilled.

But no, it hasn’t been fulfilled, for the more I see, the more my thirst for seeing grows! But God has given me only two eyes; how much can I see with them? Why hasn’t He given me many eyes? I am not able to express in words all that I see and think!

Each high summit, each creek first seems to say, “Look at me, look at me!” When I behold it with eyes wide open from astonishment, they seem to smile and say with a frown, “Are you looking at me? Remember my Creator!” They are right. Looking at a painting, one can understand the skill of the painter. Or does anybody know anyone only by name? How huge, how extended, how great are these foothills of the Himalayas for us! And how humble is the Himalayas’ place in the world created by that Great Artist! Even calling it a grain of sand would make it too big!

Does it now amount to treason if we don’t sing the praise of the Creator’s qualities with these beautiful eyes, ears, and this mind of ours? Only if we wor-ship with our mind, brain, and heart do we attain satisfaction. Worship is not achieved, in my opinion at least, by just pronouncing some words that one has learnt by heart like a parrot. Where is the heart’s emotion in such worship? Where is the enthusiasm? When looking at the beauty of nature, mind and heart break out in unison, “Only God is worthy of praise! Only He is laudable!”

Then there is no need to voice all these words. “A Frog in a Well Seeing the Himalaya” is today herewith concluded.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.