[Readmelater]

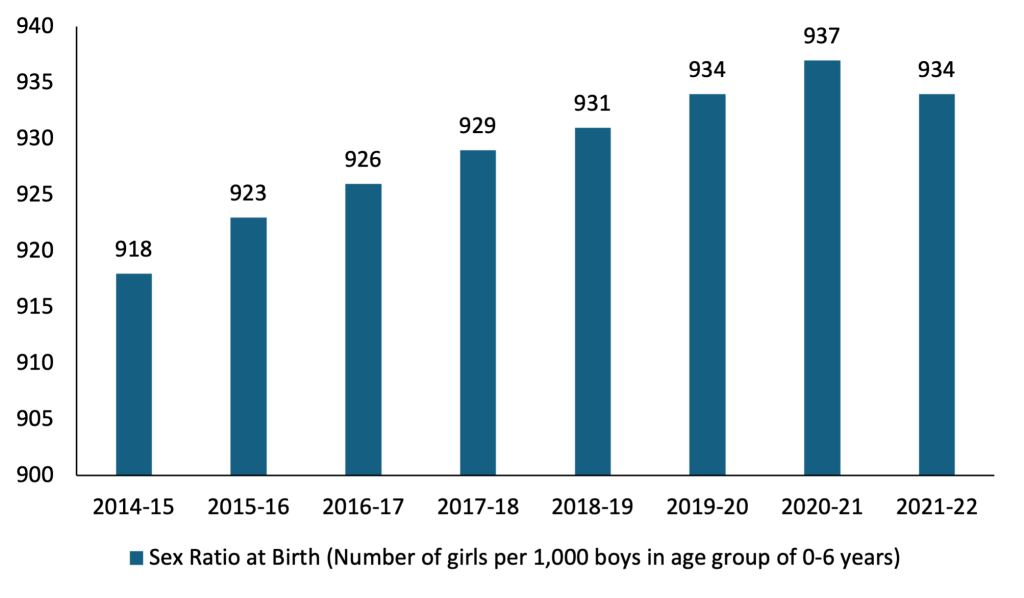

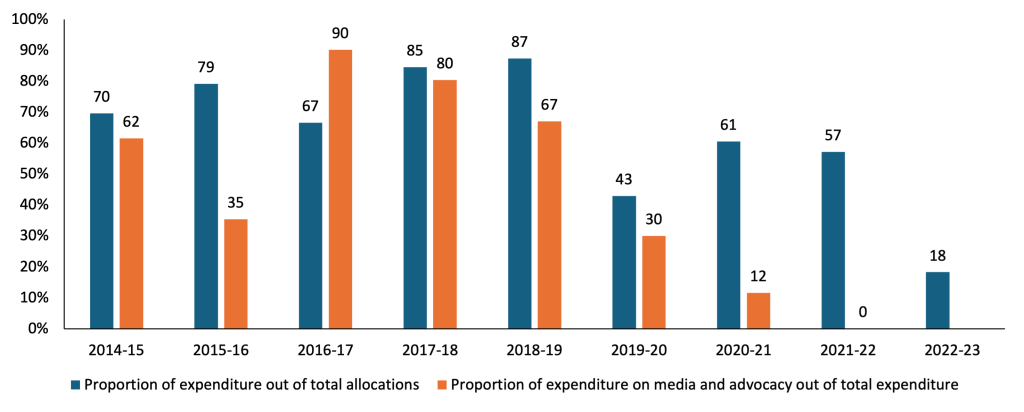

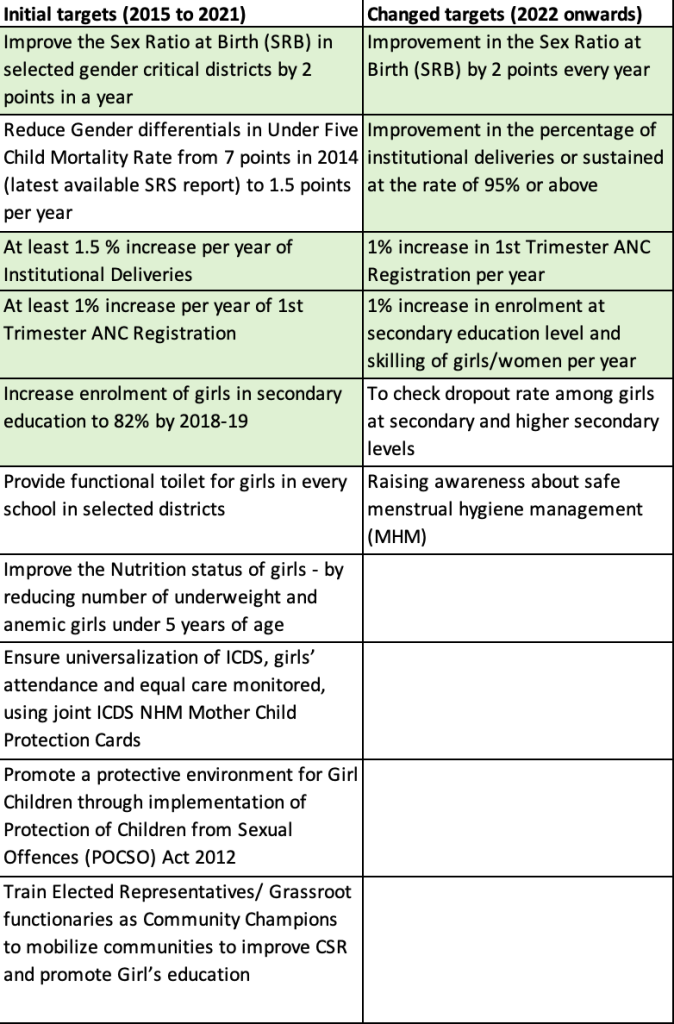

Has Beti Bachao Beti Padhao’s Media Advocacy Focus Achieved The Desired Outcomes?

The improvements in parameters related to the girl child cannot be solely attributed to the scheme’s implementation

Photo: Ministry of Culture, Government of India

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.