Rural Jobs Scheme Has Yet To Benefit The Most Marginalised Women Of Maharashtra

Our investigation across eight villages showed just one project available under MGNREGS, forcing women to migrate as far as Odisha in search of work

- Priyanka Tupe

Dressed in red uniform shirts, Kalyani*, 7, and her brother Rohan*, 6, were in a rush to leave for the community learning centre run by a local NGO in Dhangarwadi village in Maharashtra’s Yavatmal district, 700 km from Mumbai. It is their aaji (grandmother), well into her late 50s, who helped them get dressed for school.

“I do all this because their mother, Tanabai, resumed work yesterday. She had come home for a day to see the children but I don’t know when she will come home again,” said Gangubai Jadhav.

Tanabai, 30, works as a salgadi (bonded labourer) with a farmer family in Yavatmal, herding sheep and goats. She earns around Rs 50,000-60,000 a year and is allowed only one trip home for two days to see her children. The day before we met the family, Tanabai had said goodbye to her children, her eyes brimming.

In villages across Yavatmal, Amravati and Akola, Behanbox met many young children, especially from the Scheduled Tribe (ST) and nomadic and denotified (NT-DNT) communities such as the Phase-Pardhi, Pardhi and Dhangar communities, whose parents have migrated in search of work to West Bengal, Odisha, Chennai, Delhi and Mumbai. The children have been left in the care of elderly grandparents, mostly grandmothers, or even older daughters, some of whom are barely 10.

Gangubai said she knew nothing of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), which could have provided her daughter work in the village itself. The sarpanch or rojgar sevaks had not told her about it. (Rojgar sevaks are job supervisors appointed by gram panchayats and paid from MGNREGS funds and their tasks include securing jobs for villagers, maintaining attendance and facilitating payment for scheme work.)

MGNREGS, introduced under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005, guarantees a minimum of 100 days of work (manual labour) to all rural households that live on unskilled manual work. It is framed as a right and those who are denied are entitled to an unemployment allowance.

Shobha Shiwankar, an Adivasi from a particularly vulnerable tribal group (PVTG), Kolam, in Kharad village, knows nothing about MGNREGS. She is in dire need of employment because her earnings from selling forest produce bring her very little money. “I get Rs 100-150 a day collecting mahua, lac and so on. But this isn’t a fixed income, so somedays I get nothing because of deforestation,” said Shiwankar. She and her family survive mostly on the public distribution system that provides her 10 kg foodgrains for free.

Our colleagues reporting from other states for the forthcoming elections also found echoes there of these stories, as we detail later. As India readies to vote a new government, Behanbox is taking a close look at the MNREGS, its functioning and the exclusions across different states. This is part of our election reporting project where we are taking stock of the performance of critical schemes for women from the ground.

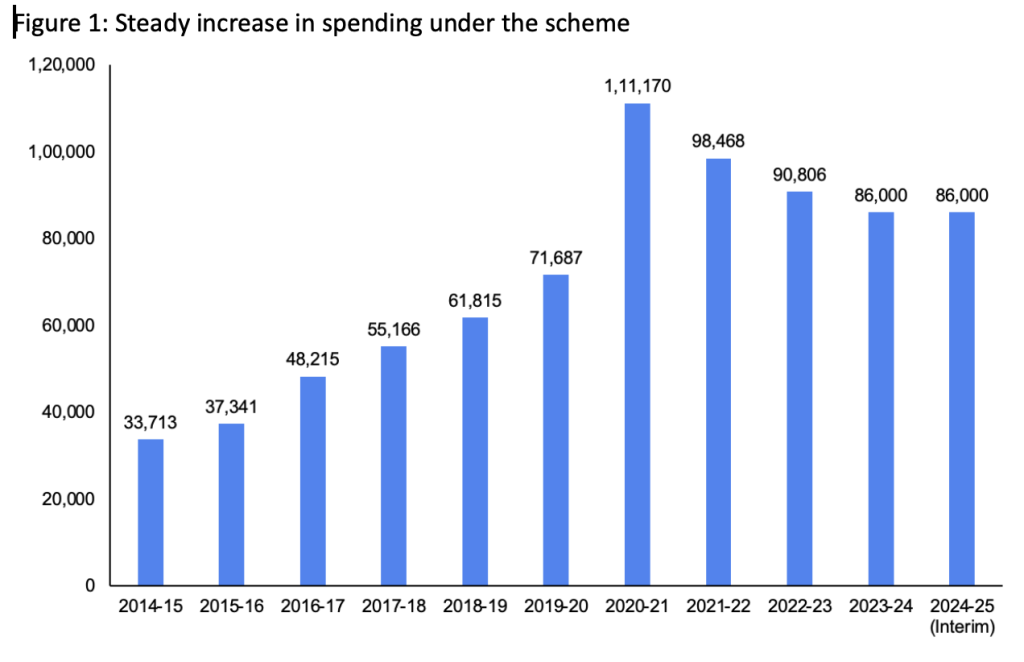

The rural jobs scheme is critical for poverty alleviation and employment, particularly for women because it promises equal wages and financial autonomy. There has been a steady increase in spending under NREGS. This spiked in 2020-21 to Rs. 1,11,170 crore because of COVID-induced reverse migration to villages, as per the scheme MIS report. Thereafter the spending kept declining every year. However, the demand for MGNREGS work has not declined. Here is why: in the interim budget of 2024-25, Rs 86,000 was allocated for the scheme but the actual spending for 2022-23 was Rs 90,806, suggesting a shortfall in resources.

“In the last ten years, NREGA has radically departed from the vision of a rights-based, decentralised employment programme where workers have a say at every step,” said Jean Dreze, a development economist and one of the architects of MGNREGS. “Workers have been turned into passive recipients who are at the mercy of centralised and technocratic processes beyond their understanding. Opaque and chaotic wage payments epitomise this state of affairs. Without a guarantee of timely payment, the purpose of NREGA is roundly defeated.”

8 Villages, One Scheme

Asmita and Anju Pawar, two young college students in Hinglaspur Village of Amravati are taking care of their year-old, niece Chinky*. Their mavashi (maternal aunt) Ravita Pawar died by suicide in December 2023 when she could no longer cope with the stress of unemployment and domestic violence.

“It’s very common here for women to migrate to other states for work, especially those from tribal communities. Most welfare schemes are inaccessible to them. The extreme poverty, unemployment, and migration of adults affect children, more so the girls who are pushed into child marriage [by the crisis],” said Pranali Jadhav, an activist from Yavatmal.

BehanBox travelled to eight villages in Amravati, Akola and Yavatmal districts and found that none of these – Titva Beda, Vadala, Januna and Tiwasa in Akola, Kharad and Mandla-Dhangarwadi in Yavatmal and Hinglaspur and Diwankhed in Amravati – had ongoing work schemes under MGNREGS. Diwankhed in Amravati was the only exception where a forestation project was underway.

In Maharashtra, an average household got work for just 45 days under the scheme, much below the Indian average of 51 days in 2023-24 (as on March 21, 2024), according to the MGNREGS MIS. The scheme also reserves 33% of jobs for women. In 2023-24 (as on March 19, 2024), of all the unskilled and skilled workers, only 17% were female.

Women working at Diwankhed complained that their wages had not been paid since November 2023. Vidya Bansode, 42 from Chikhali, a neighbouring village, has been doing MGNREGS work for the last three years. “I have not received any wages since last Diwali (November 2023) in my bank account. I buy groceries using credit,” she said.

At lunch, all that the women get to eat are 3-4 rotis with a few tablespoons of a watery curry. Delayed payments do not allow them a more nutritious diet, they said. “Kirana tar udhar milto, bhaji ghyala tar rokh paise pahije na. Aamhi kadhi nusti dal banavato, kadhi bhaji…eka velela ekach karto (vegetables cannot be bought with credit. We need cash so we make either dal or sabzi but not both at a time),” said Kamal.

MGNREGS has been helpful for increasing the average share of consumption items such as vegetables, fruits, oil, meat and eggs and decreasing that of less expensive food items such as cereals, pulses and milk, as per this 2020 research paper published in the Economic and Political Weekly. MGNREGS has also helped reduce malnutrition in Rajasthan among the infants.

But we found that the patchy implementation of MGNREGS has a direct impact on the lives of women and children. Kamal from Amrawati’s Chikhli village, who earned Rs 1800 in the last six months of work under the scheme, has been coping with food scarcity.

“My heart breaks when I can’t even buy books and pens for my children because my wages have not been paid. See, this is how our life is: tomorrow our children will also become labourers if we can’t provide them an education,” said Kalpana Mirase, a MGNREGS beneficiary, who has not been paid.

Mirase’s story indicates how poverty can turn intergenerational.

‘Oppressed Castes/Tribes Don’t Get Jobs’

Pardhi, Phase-Pardhi, Dhangar communities tend to be excluded from MGNREGS, we learnt in interviews with women in all the villages we visited. All Pardhi households of Titva Beda village in Akola (approximately 180) migrate to Odisha and West Bengal in search of livelihood every year.

Sangeeta Pawar is one of them. She has been travelling to Sambalpur in Odisha in search of work every year for the last 22 years. There she buys cutlery and then sells it door-to-door in Kolkata from November to March/April. She does not have agricultural land or any other resource to earn a livelihood.

“We Pardhis don’t get any work under any scheme from the sarpanch, let alone MGNREGS. Most of us don’t have documents like Aadhaar cards. So we have to take loans from savkars (private money lenders) with interest rates of 5-10 % for our basic needs. This house we are building using a loan,” said Sangeeta pointing out at her house which is under construction.

According to MGNREGS MIS, in 2023-24 (as on March 19, 2024), of the over 17 lakh households provided employment in Maharashtra, only 9% and 24%, respectively, belonged to SC and ST households.

Pardhi Bedas, Kolampods, Dhangar bastis are settled on the periphery of villages and this affects their easy access to gram panchayats, sarpanchs and rojgar sevaks. There are no targeted interventions to ensure MGNREGS outreach to ensure the inclusion of those from marginalised groups such as SC, ST, NT, DNT, we found.

“Even when I was the sarpanch in 2015, I couldn’t make the proposals of the work under NREGA which will provide work for my (Pardhi) community. I am not educated and upper caste gram panchayat members used to get my thumbs on the blank papers every time.” said Phuljababai Rathod of Titva Beda village.

Pardhis were traditionally hunter-gatherers. But hunting is now banned under the wildlife protection act and jobs are generally unavailable for them. “Police seize our weapons and most of the time slap us with a fine of Rs 10,000-20,000. Forest produce is becoming scarce and we don’t own any land. Should we starve and die?” asked Savitri Chavhan, rage writ large on her face. She does not even know what a job card looks like.

Sarpanchs from marginalised social groups said they do not have the real power to make a difference. Krushna Ahire, a sarpanch from the Dhangar community in Dhangarwadi village, pointed out that though the rojgar sevak of his village belongs to a Scheduled Caste he did not insist on the inclusion of more Dhangars in the scheme. “He is corrupt and takes Rs 1000 per job card,” Ahire alleged. Other villagers and a local activist, Dhammand Bondade, also said that there were corrupt practices in the distribution of job cards.

However the Annual Master Circular 2022-2023 of MGNREGS clearly states the need to focus on marginalised groups: “The households that are listed as vulnerable or deprived as per the socio economic caste census should be issued job cards on priority. There is a possibility that many landless households dependent on manual casual labour for ‘livelihood’ category (as per SECC 2011) are not yet registered under the scheme. The states/ UTs should proactively reach out to these landless and manual casual labour households and register these households who do not have job cards and are willing to work under Mahatma Gandhi NREGS.” Only 9% and 14% SC and ST households, respectively, had received job cards in Maharashtra in 2023-24.

The women we interviewed do not know that they have a right to the jobs scheme under. And even those who do and find work, do not know that there are provisions under the MGNREGA Act for facilities such as a creche at the workplace, medical aid, shed, drinking water facility and so on.

Pardhi women from Diwankhed and Hinglaspur village also alleged caste atrocities related to work on MGNREGS. Dinesha Pawar, 22 from Diwankhed said: “Very few from our community get jobs but when they do, they are bullied and harassed by others (dominant castes). If we go to people’s farms or wells [to work], we are not allowed to touch vessels and tools. We are still criminalised and beaten up for any theft [committed around us]. We are compelled to make alcohol at home and sell it and there is the constant threat of a police raid, beatings, abuse and a fine.”

Allegations Of Corruption

Proposals for public welfare works to be covered under MGNREGS are not approved easily. “When we go to the Panchayat Samiti office with our proposals, we are asked to pay a 10% commission of the total project estimate,” said Manda Bahadare, the sarpanch of Tiwasa village in Akola district. “If we refuse, we are asked to go to Mantralaya (the state secretariat in Mumbai) for approval.”

We were told that different kinds of corruption are at work in the execution of the job scheme. NREGS provides 273 different kinds of works in Maharashtra, which fall under different ministerial departments. For example, tree plantation is with the forest department; while digging of wells, ponds and so on is with the agriculture department. Gram panchayats proposals are first submitted to the Panchayat Samiti where they may remain indefinitely, at least half a dozen sarpanches told Behanbox.

Often rozgar sevaks retain job cards of Illiterate workers and accompany them to the banks or ATMs to “help” withdraw cash and then extract a “commission”, said villagers.

As we said earlier, except Diwankhed there were no active worksites in any of the villages we visited. Six men were able to get some tree plantation work under NREGS in Hinglaspur village of Amravati; no woman was given any work. We asked the rojgar sevak Yogesh Raut why women were excluded from the scheme: “There is not enough work available currently and women prefer to work as farm labourers. Men do plantation work under a hot sun.”

Earlier this month, when we visited the Barshi Takli Panchayat Samiti of Akola district to understand the reasons for the lack of work opportunities and delayed wages, the officials declined to comment. They claimed that they were busy approving NREGS project proposals before the model code of conduct for the Lok Sabha elections 2024 kicks in.

NREGS workers are entitled to delayed wage compensation at the rate of 0.05% of unpaid wages per day for the duration of delay beyond 16th day of muster rolls closure. MIS data, however, suggest that the majority of pending liabilities were to cover material costs (as opposed to labour costs).

Demand For Scheme Job Stays Strong

There has been a steady increase in spending under NREGS (Figure 1). This spiked in 2020-21 because of COVID-induced reverse migration as a lot of people were moving back to villages from cities and towns. But this demand has worn off but not to the extent that merits reduction in allocations. For instance, in the interim budget of 2024-25, Rs 86,000 was allocated for MGNREGS. Actual spending for 2022-23, however, was Rs 90,806, suggesting the demand for work under the scheme is still strong.

Note: All figures are in Rs crore. Figures till 2022-23 are Actuals, or actual money spent under the scheme. The planned allocations are presented for 2023-24 and 2024-25.

The notified wage rate under NREGS for Maharashtra in 2023-24 is Rs 273.

Between 2018-19 and 2023-24, wages have increased by Rs 14 on average. The highest spike in rural wages was between 2019-20 and 2020-21 from Rs 206 to Rs 238. However, 100 days of employment is not actually guaranteed which job card holders are entitled to, according to MGNREGS Act 2005. On the other hand, public policy makers and researchers argue that 100 days of employment is not sufficient because it reduces starvation but barely reduces poverty.

People who are not given work during the 15 days from their demand, are entitled to get unemployment benefits or allowances, but no woman we spoke to was aware of this provision of the act. Sarubai Kengar received a job card a year ago but she didn’t get any work nor is she aware of the unemployment benefit.

Similar issues have been reported from Bihar. And our colleagues reporting from Srikakulam and Vizianagaram districts in Andhra Pradesh have found that wages have not been paid since January 2024 after the Sankranti festival. Uttar Pradesh has such instances too. “NREGA workers in Uttar Pradesh have not received wages since October 2023. Financial distress is pushing people into selling or depositing gold and silver ornaments for loans. The villages I regularly work with are deserted because of migration for livelihood,” said Richa, senior trade union leader from Sangtin Kisan Mazdoor Sangathan in Uttar Pradesh.

[ Tanya Rana contributed to this story with policy and data.]

BehanBox’s Feminist Election Newsroom has created accessible video voting guides to equip our audience to become an informed voter. We have explainers on “How To Register Your Vote As a First Time Voter” – English, “अपना वोट रजिस्टर कैसे करे? – Hindi”

“How To Shift Your Vote If You Have Migrated”, “How To Update Your Gender and Name On Your Voter ID”, and “How To Mark Yourself As A PwD Voter”.

We have more resources coming up. Keep watching this space for more. To sign up for BehanBox’s Feminist Election Newsroom, click here.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.