The devil, as the cliche goes, is in the details. But so keen are we to grasp any passing skein of hope that we have begun celebrating all kinds of announcements, deals, and agreements before we know anything about the nitty gritty or what it implies. It happened with the FTA with the EU, the so-called Trump deal and now the 2026-27 budget. Take a close look and you start to question the enthusiastic and premature optimism.

As usual, this budget too, we decided to not jump in and wave our arms in triumph as many pink papers and others did with hurrah headlines and over-the-top illustrations. We took a breath, stepped back and invited analysts with a firm footing in their subject to take a long, and hard look at the details. Our analyses will be spread over the month and will focus on issues that are close to our heart – what the allocations mean for women, marginalised groups, employment, and carework. Exactly what are the resources in schemes relating to them, what is for real, what is sleight of hand, who stands to benefit and who will lose. We will be addressing these questions.

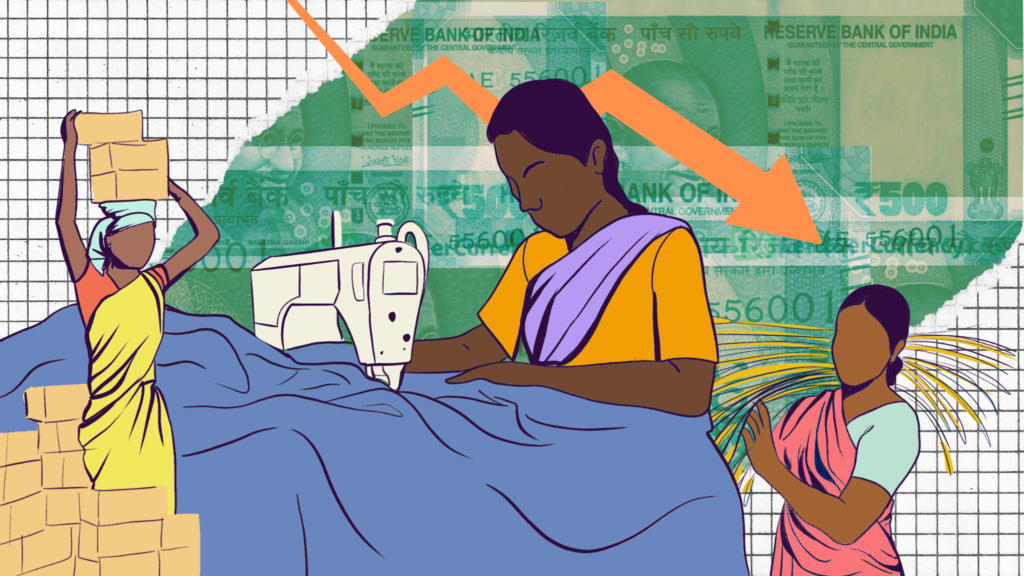

The first of these we published this week, a sharp and clear-eyed study by Varna Sri Raman of what the budget holds for women’s employment. Central budgets have critical linkages to our daily lives but most of us are so intimidated by the numbers and jargon we rarely progress beyond headlines and bullet points. Varna is a rare development economist who lays out the dots and then links them methodically for us to understand what the officialese hides.

Here is what she concludes – the budget cuts this year to the MGNREGA funds impact the most vulnerable – rural women in the informal work sector from mostly poor states. The arithmetic she points out is direct: MGNREGA funding dropped from Rs 86,000 crore to Rs 30,000 crore. The PM Viksit Bharat Rozgar Yojana, an employment incentive administered through the Employee’s Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO), received Rs 28,715 crore. The first programme serves rural households, in which 59% of workers are women. The second serves formal-sector establishments, in which 75% of new subscribers are men.

The lines become clearer if you look at who benefits the most from MGNREGA, further imperilled by the newly minted VB-GRAM-G which changes a legally guaranteed employment right in11 into a scheme and banks heavily on state funding. It is the women from the poorest of states who bank on the Act the most.

“Sunita Devi understands this arithmetic even if she has never read a budget document. She is a 35-year-old mother from Bihar who supports her family through MGNREGA. The programme enables her to work locally, manage household responsibilities, and earn a fair wage. When I spoke with her, she kept returning to the same worry: fewer jobs in her village, less money for her children’s school fees. Her state government now needs matching funds, which it may not have,” says Varna.

Wait and watch, and check how the guidelines pan out in the future to see if these conclusions come true. We fear that they might.

Read our analysis here.