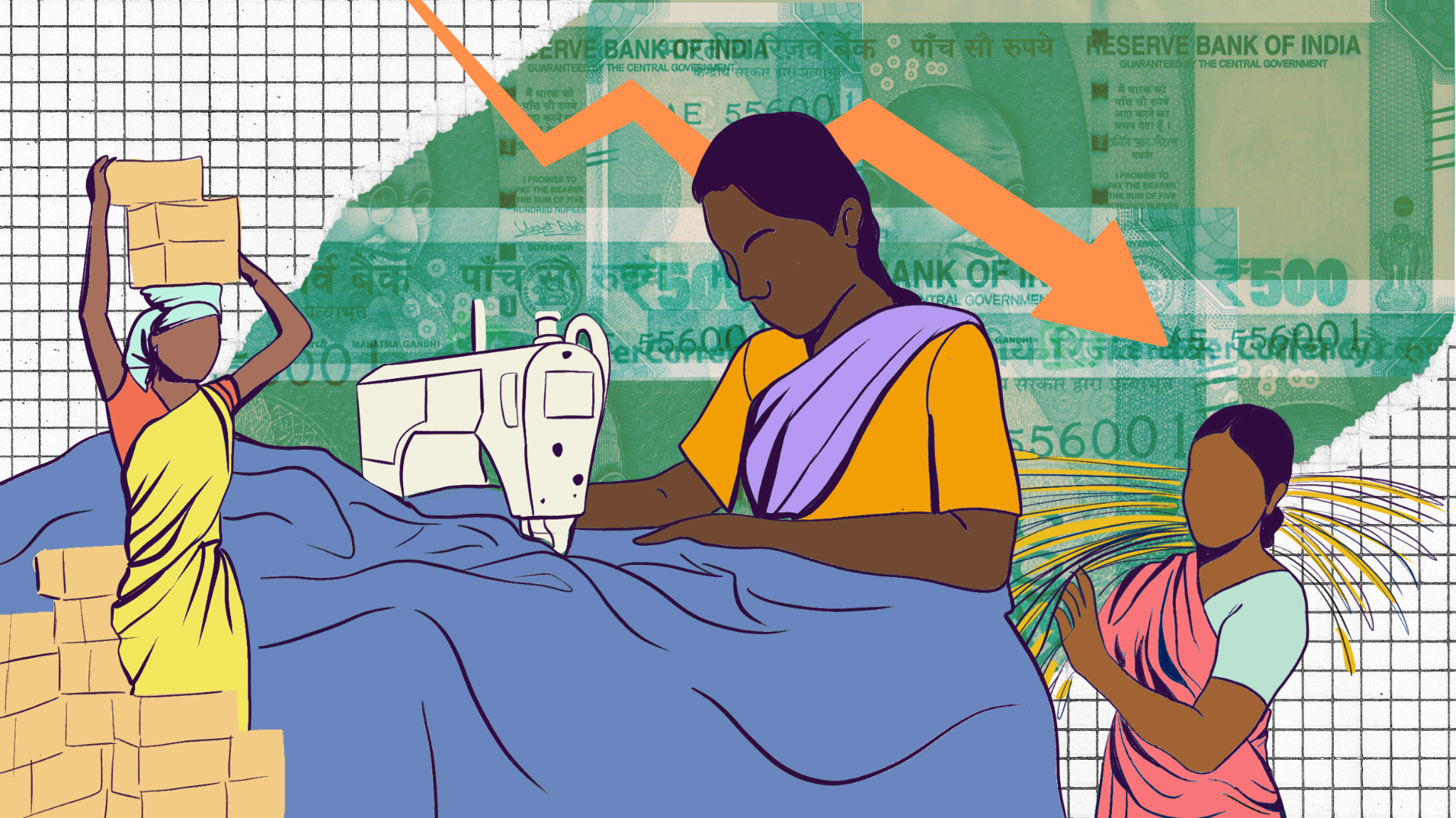

Labour In Budget 2026-27: Focus Shifts From Rural Women To Urban Men

Cuts to the MGNREGA funds impact the most vulnerable – rural women in the informal work sector from mostly poor states

This is the first report in our coverage of the Union Budget 2026-27. Follow our analysis here or on other platforms.

THE LARGEST EMPLOYER OF WOMEN IN INDIA is not a factory, not the service sector, not government offices. It is a manual-labour programme that pays individuals to dig ponds and build roads in villages. In 2023-24, 59% of MGNREGA workers were women, in Kerala, 89% and in Tamil Nadu, 87%. Even in Uttar Pradesh, where women’s workforce participation is notoriously low, the share rose from 34% in 2020-21 to 42% by 2023-24.

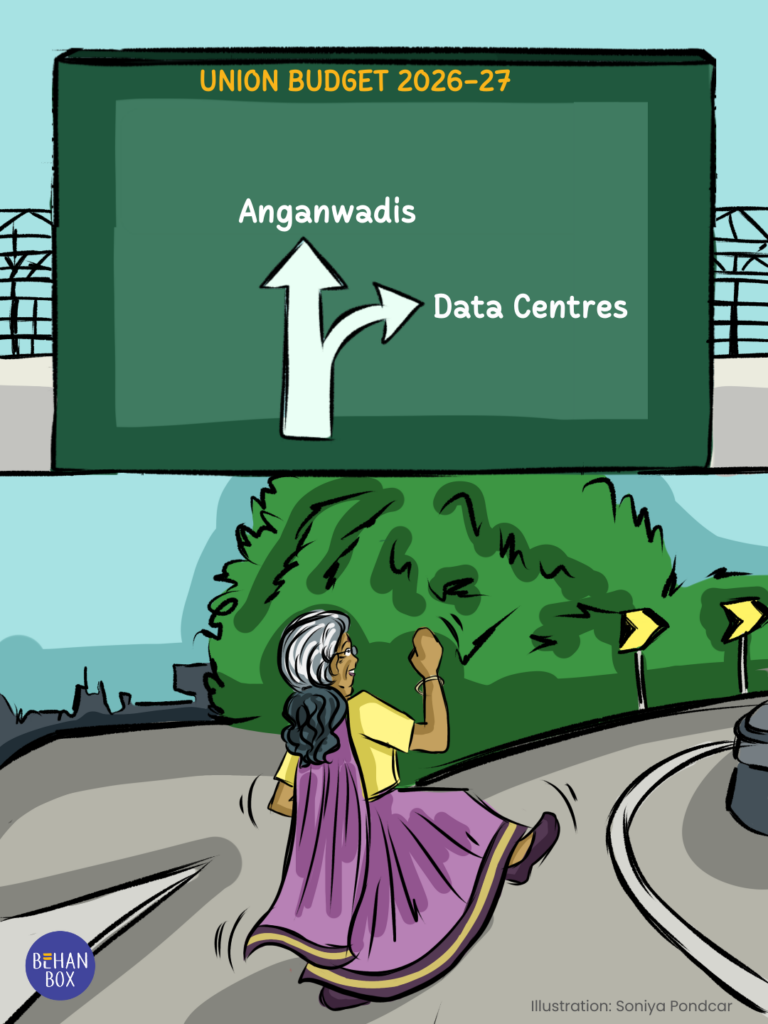

Budget 2026-27 cuts the funding for this programme by 65% and shifts resources toward urban formal-sector workers. This is not a minor adjustment. It is a reallocation from poorer to richer, from informal to formal, and from women to men.

The arithmetic is direct: MGNREGA funding dropped from Rs 86,000 crore to Rs 30,000 crore. The PM Viksit Bharat Rozgar Yojana, an employment incentive administered through the Employee’s Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO), received Rs 28,715 crore. The first programme serves rural households, in which 59% of workers are women. The second serves formal-sector establishments, in which 75% of new subscribers are men.

This article traces the mechanics of that shift: where the money is going, who loses, who gains, and how the administrative fine print facilitates the reallocation.

Before examining what the budget does, it helps to understand what MGNREGA is.

MGNREGA is not a scheme, it is a law. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act was passed by Parliament in 2005. Section 3(1) says every rural household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work “shall be entitled to” at least one hundred days of wage employment per year. If you apply for work and do not receive it within 15 days, Section 7 says you are owed an unemployment allowance.

That word “entitled” carries legal weight: it means a citizen can go to court. A scheme, by contrast, exists at the pleasure of the executive, it can be modified or discontinued without Parliament. MGNREGA has survived multiple administrations precisely because changing it requires legislative action.

Where The Money Is Going

The cut to MGNREGA is Rs 56,000 crore. At an average daily wage of Rs 300, that translates to roughly 190 million lost workdays. Each of those days was a day a rural household could have earned income. Now it cannot.

The government announced VB-GRAM G (Viksit Bharat-Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission, Gramin), with a budget of Rs 95,692 crore and a commitment to 125 days of guaranteed employment. Whether this new programme will replace MGNREGA, run alongside it, or absorb it remains unclear. No operational guidelines have been released. Workers do not know which programme they now belong to. The NREGA Sangharsh Morcha, representing workers across multiple states, has argued that the current allocations are 42% of what is what will be required to actually finance this guarantee. At a 60% central share, the government needed to allocate 2.3 lakh crore to provide 125 days work to all active households.

The government presents the combined allocation of Rs 1.26 lakh crore (MGNREGA plus VB-GRAM G) as an expansion over last year’s MGNREGA budget of Rs 86,000 crore. But three changes in the administrative structure tell a different story.

The cost-sharing change. Under MGNREGA, the Central government pays 100% of wage costs. States contribute only to the material costs of assets such as roads and ponds. Under VB-GRAM G, according to the Notes on Demands for Grants, the ratio shifts to 60:40 between the Centre and states.

The states with the highest MGNREGA demand are Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and eastern Uttar Pradesh. These are also states with the weakest fiscal capacity. When the Centre shifts 40% of wage costs to states, it is these states that will struggle to match. The Rs 95,692 crore looks generous until you calculate that states must now find Rs 38,000 crore from their own budgets to access it fully. Bihar cannot do this as easily as Maharashtra; Gujarat can absorb the cost but Jharkhand cannot.

Sunita Devi understands this arithmetic even if she has never read a budget document. She is a 35-year-old mother from Bihar who supports her family through MGNREGA. The programme enables her to work locally, manage household responsibilities, and earn a fair wage. When I spoke with her, she kept returning to the same worry: fewer jobs in her village, less money for her children’s school fees. Her state government now needs matching funds, which it may not have.

The legal status change. VB-GRAM G appears to be a scheme rather than a law. If this is correct, the “guarantee” in its name is an intention, not an enforceable right. The unemployment allowance in Section 7 of MGNREGA is a legal obligation. There is no indication that VB-GRAM G contains anything equivalent.

The 60-day blackout. Section 6(1) of the VB-GRAM G Bill states that “no work shall be commenced or executed under this Act, during such peak seasons as may be notified.” Section 6(2) requires states to notify “a period aggregating to sixty days in a financial year” during which work “shall not be undertaken.”

The 125-day promise must therefore be compressed into a window of 305 days. Jean Drèze, one of the architects of the original MGNREGA, has called this a “switch-off clause”.

The assumption is that workers can find private agricultural employment during peak seasons. A three-state study by the non-profit SOPPECOM (Society for Promoting Participative Ecosystem Management), which surveyed nearly 3,000 rural women, found the opposite. More than 65% reported a decline in agricultural work availability. In Punjab, women receive barely 35 days of agricultural work per year. In Telangana, around 60 days during the entire peak season. As the researchers put it: “It is not MGNREGA that pulls workers away from farms; it is agriculture itself that no longer provides sufficient employment.”

For women, the blackout is worse than it sounds. “Peak season” agricultural work is often unpaid labour on household plots. The 60-day restriction removes the guaranteed fallback precisely when private wages are most depressed due to labour surplus.

Who Loses

The losers are specific. They are rural, female, informal, and concentrated in the states that can least afford to compensate.

The India Time Use Survey 2019 explains why rural women cannot simply shift to formal employment. Rural women spend 299 minutes daily on unpaid domestic work: cooking, cleaning, childcare, and household maintenance. Rural men spend 97 minutes. Add water collection and firewood gathering, and rural women spend over six hours daily on work that earns no income. Women devote more than a quarter of every 24 hours to unpaid activities; men devote around 7%.

Economists call this time poverty. The term is precise. The ILO’s global analysis found that women with care responsibilities are 16.6 percentage points less likely to participate in the labour force than single women. For men, living with care recipients actually increases labour force participation. Women are not choosing informal work over formal work. They are constrained by care responsibilities that demand flexible, local employment.

MGNREGA was designed with these constraints in mind. Schedule II of the Act mandates equal wages for men and women. In the open labour market, women casual labourers earn roughly 22% less than men for equivalent work. Under MGNREGA, that gap closes.

The Act requires work within 5km of the worker’s residence. A woman who already spends five hours on domestic work, plus time fetching water and firewood, cannot add two hours of travel to a distant worksite. The distance limit is not an administrative detail. It is what makes the programme accessible.

The programme is demand-driven. A woman registers for a job card and applies for work; the state must provide it. She does not need a contractor to select her or a male relative to negotiate on her behalf. The state is the employer, and the process is formal.

Rekha, a 32-year-old MGNREGA worker from Jharkhand, showed me what this looks like in practice. Her day begins before dawn: breakfast, children ready for school. By 8 AM, she joins her neighbours at a nearby worksite. She is back by 12:30 PM to serve lunch and check on her elderly mother. After a break, she returns to work until late afternoon. She never travels more than 5km from home. MGNREGA enables this balance between paid and unpaid work, formal employment does not.

These design features explain why 59% of MGNREGA workers are women. These provisions were not accidental, they were written into the Act because earlier employment programmes had failed to reach women.

Who Gains

The gainers are also specific. They are urban, male, formal-sector, and concentrated in richer states.

The PM Viksit Bharat Rozgar Yojana provides up to Rs 15,000 to first-time formal-sector employees and subsidises employer contributions for new hires. EPFO covers establishments with 20 or more workers under the EPF Act, 1952. It does not cover agricultural labourers, domestic workers, or construction workers on small sites.

The geography tells the story. The states with the highest EPFO enrollment are Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and Haryana, which are urban and industrialised. As we said earlier, the states with the highest MGNREGA demand are Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Uttar Pradesh (especially its eastern areas), which are predominantly rural and have few formal-sector jobs.

A Rs 15,000 incentive does not create factories in Purnia or Koraput. It subsidises hiring where jobs already exist. The budget is not neutral between these two groups. It takes from one and gives to the other.

How the Fine Print Does the Work

The shift from rural to urban, informal to formal, does not happen through a single dramatic announcement. It happens through administrative design.

Cost-sharing. When the Centre paid 100% of MGNREGA wages, every state could offer work regardless of fiscal capacity but the 60:40 ratio pegs the programme’s reach on state budgets. Bihar and Jharkhand, which have the highest female dependence on MGNREGA, are also the states least able to match funds. The change appears technical; its effect is to reduce employment guarantee where women need it most.

Legal status. As we said earlier, when an employment guarantee law is transformed into a scheme, workers cannot go to court to demand work or seek delayed wages. The guarantee then is not meaningful any longer.

Seasonal restriction. When work is available year-round, women can access it when their care responsibilities allow. A 60-day blackout during “peak season” shrinks the effective guarantee. The assumption is that agriculture will provide work during these months. Field evidence indicates that it will not, and women, in particular, will lose guaranteed income precisely when private wages are most depressed, as we said.

None of these changes appear in the headlines; they appear in the Notes on Demands for Grants, in the text of the VB-GRAM G Bill, and in fund-sharing ratios buried in budget annexures.

Consistent Pattern Of Cuts

The MGNREGA shift is not isolated. The budget exhibits a consistent pattern in its treatment of programmes for women. Budget 2026-27 allocates Rs 3,200 crore to Mission Shakti, the umbrella scheme for women’s safety and empowerment. However, the government expects to spend only Rs 2,000 crore in 2025-26, representing a 37% underspend. SAMBAL aimed at women’s safety was budgeted at Rs 629 crore and revised to Rs 322 crore; and SAMARTHYA that includes support services such as hostels and creches was budgeted at Rs 2,521 crore and revised to Rs 1,677 crore. The Palna creche scheme targets 1,000 creches enrolling 20,000 children. India has more than 125 million children under 6 years of age. The gap between need and provision is not marginal.

The Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana provides Rs 5,000 for a first child, at Rs 300 per day, covering 17 days of lost wages. Recovery from childbirth takes weeks; breastfeeding requires months. The National Food Security Act mandates Rs 6,000 per child; PMMVY provides even less.

Meanwhile, the government relies on nearly 35 lakh women to deliver child nutrition and primary healthcare. Anganwadi workers and helpers number approximately 25 lakh and ASHA workers approximately 10 lakh. The state classifies them as “honorary workers” or “volunteers”. The Central contribution to an Anganwadi worker is Rs 4,500 per month. “Honorary workers” are not covered by minimum wage laws, provident fund, or pensions. In 2020, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Labour recommended formalising their employment status. It has not happened.

MGNREGA was different. A woman who works under MGNREGA receives a wage deposited into her bank account. She is legally an employee, and the state is her employer. The programme does not refer to her compensation as an “honorarium”.

Government data show rural women’s labour force participation (LFPR) rose from 24.6% in 2017-18 to 47.6% in 2023-24. Some cite this as evidence that women’s employment is improving and MGNREGA matters less than it used to. This misreads the data. The Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) measures the proportion of the population that is employed or actively seeking employment. It does not measure what kind of work. A woman who works on her family’s farm without pay is considered used. So does a woman who rolls beedis at home for Rs 50 a day. Most of the increase in rural female LFPR stems from self-employment and unpaid family work, rather than waged employment of the kind MGNREGA provides.

MGNREGA offered a specific benefit: guaranteed wage employment at a known rate, paid into a bank account in the woman’s name. For many rural women, this was the only source of cash income entirely their own, not mediated through a husband or father. A higher LFPR does not imply that women require this less, it may mean they need it more.

Wait And Watch

In the coming months, the operational details will determine whether VB-GRAM G protects or abandons what MGNREGA achieved. What we need to look out for are the following:

-

The Operational Guidelines

Upon release, it has to be checked if the legal guarantee of employment within 15 days remains in effect. Also if the 33% women's participation floor – that mandates that at least one-third of beneficiaries be women – is maintained.

-

State Response to Cost Sharing

Observe which states struggle to match the 40% input; it is the women workers in these states who will lose access to work first.

-

The Seasonal Blackout

Track which states notify their 60-day periods and when and watch whether women actually find agricultural employment during these months.

-

The Payment Architecture

MGNREGA's direct bank payments were central to women's financial inclusion. VB-GRAM G routes payments through household heads or SHG accounts, breaking this direct pipeline.

During the pandemic, MGNREGA provided work to 7.6 crore households. Women made up 53-54% of person-days. No other government programme absorbed rural distress at that scale. In Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Jharkhand, MGNREGA is often a woman’s first experience of earning a wage in her own name, opening a bank account in her own name, and receiving payment directly rather than through a male household member.

That is economic identity, not just income.

Budget 2026-27 puts it at risk, not through dramatic cancellation, but through cost-sharing ratios, legal status changes, and seasonal restrictions. Funds are shifting from programmes serving rural women to programmes serving urban men. The reallocation is real. The question for anyone watching this budget is straightforward: follow the money, read the fine print, track who bears the cost.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.