Postcards #11: People’s Movements And Hunger Strikes For Palestine

This month in Postcards: remembering the mellifluous Nirmala Devi, how to slowmaxx romance, and poetry in times of violence

We write to you about the people, places, and ideas that brought team BehanBox joy this month. One postcard, every month.

Keeping Hope and Resistance Alive

For most people, ‘New Year’ changes very little. Labour exploitation cycles continue and bombs drop but people find small ways to experience joy amidst it all. For me, the imagination of one thing ending and another beginning serves as a powerful reminder to renew our resolve–to fight for justice, to keep hope alive, and hold on tightly to the collective humanity and love we still carry within us.

On January 1, I was on a call with a dear friend who spent much of 2025 making the rounds of a British prison, where their friend and comrade Jon Cirk had been on hunger strike after being wrongly incarcerated in support of pro-Palestine action. They spoke of how the hunger strikers’ resolve revived Britain’s Palestinian movement, strengthened community-building and reinforced ideological steadfastness at a time when individual comfort is so often placed above collective freedom.

Weeks later, I found myself among women in Palghar who moved with similar resolve, wisdom, and care–the same spirit I encountered in the writings of the hunger strikers and in the words of my comrades. As they marched steadily in black saris, caps, and sunglasses, I witnessed what becomes possible when trust and collective confidence take root, and just how much love frightens the powers of this world.

As I think about the possibilities this year holds, and my own place in realising them, I return to the words of Heba Muraisi, a 31-year-old incarcerated Palestinian activist who ended her 73-day hunger strike on January 15 this year:

“Today, I join my comrades and begin my hunger strike…I want to make it abundantly clear that this is not about dying, because… I love life, and my love for life, for people, is the reason why I have been incarcerated [by the British government] for 349 days now… This is for the mothers who can’t bury their children, for the fathers who had to bury all of theirs. For the children who have no family left and too young to understand why. And for my family – who I don’t even know if they’ve made it out of Rafah.”

Anjali

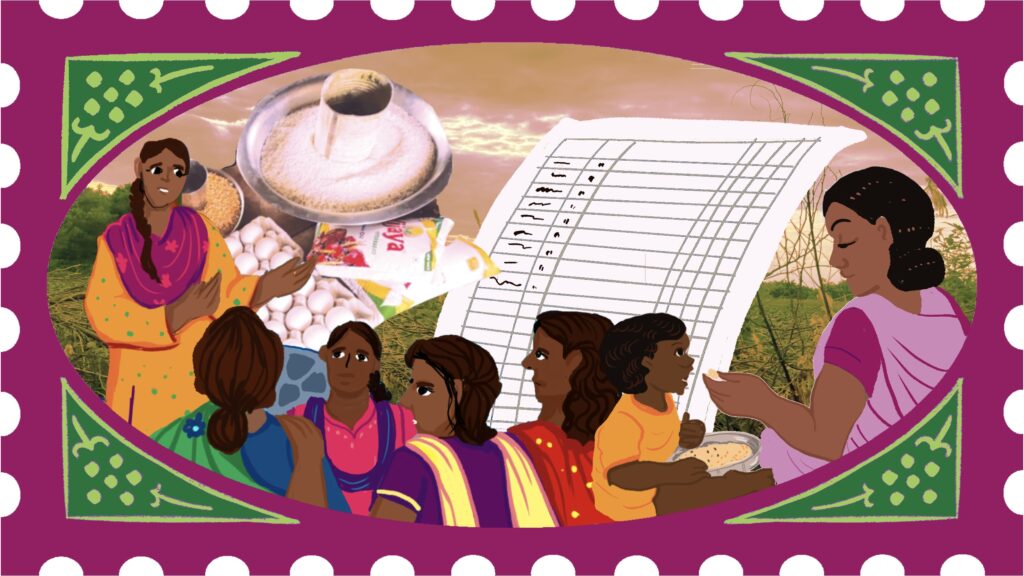

A People United

The year was 2000. I had just taken a breather after my first year of a PhD, packed my bags, and boarded a rickety Rajasthan Road Transport bus to Beawar.

“Come for this jan sunwai,” someone urged me. I had recently joined Jean Drèze and others in the Right to Food movement, walking from village to village—mostly on foot—collecting household asset and consumption data to demonstrate something the Indian state seemed reluctant to acknowledge: that far more people lived below the poverty line than the World Bank’s estimates suggested.

A jan sunwai—people’s hearing—was a radical experiment born in the dusty villages of Rajasthan. It was a forum where ordinary citizens demanded answers from the State and held their representatives publicly accountable. It was the best of times and the worst of times. Starvation deaths stalked rural India, even as structural adjustment programmes pushed by the World Bank nudged the State to retreat from welfare. This was also a time when people began asserting adhikar in the form of the right to food, information, and work movements.

We camped in a small village near Beawar, sleeping in a government school hall. Evenings were spent listening to Jean, Aruna Roy, Nikhil Dey, Shankar ji, and others pore over mountains of data from social audits conducted by villagers themselves—wage workers, unemployed men, women. The numbers laid bare the chasm between what the State claimed to have spent and what people actually received. This was before Excel spreadsheets became mainstream, before the rise of the “data journalist.” That night, we cooked and shared a communal meal of dal baati.

At the jan sunwai ordinary people presented raw, searing testimonies and asked pointed questions of the government officials, MLAs, BDOs, and other agents of the state of where their money was spent. For the first time, I witnessed the power of collective voice. A social contract as it should be.

There was acrimony, even moments of violence. But something profoundly transformative was taking shape when people roared ‘Hamara paisa, hamara hisaab (Our money, our accounts).’

These memories resurfaced recently as MGNREGA—the right to work Act born from precisely these struggles—was dismantled by the government. Remembering those days reaffirmed a deeper truth: organising is the only way forward. That is why the sea of red from Palghar in Maharashtra where fishers and other wage workers marched demanding the restoration of MNREGA and protesting against the upcoming ports feels so hopeful. A people united shall always be victorious.

Bhanupriya Rao

The Tale And Times Of A Thumri Singer

The first time I heard Govinda sing–if I remember correctly, in Saajan Chale Sasural–I was taken aback. It was some snatch of a semi-classical or maybe folk song and I recall thinking, how and why did he learn these nuances. A little digging around got me the answer: his mother was the fabulous thumri singer, the late Nirmala Devi. Her voice was honey-sweet, thick, and strong. Startlingly so. It pulls you in no matter which corner of the room you are in.

Nirmala Devi is in that league of singers, mostly women, who are classified as ‘semi classical’. The off-hand labelling shows the kind of disdain in which the music is held. But the thumri, dadra, chaiti or tappa are harder to sing than anything ‘classical’ because they need a very expressive voice and an emotional projection or ‘pukar’ because the songs are often about love, longing, separation and of course, not a little mischief. Listen to Begum Akhtar, Girija Devi, Shobha Gurtu and all such singers dismissed as semi classical and notice the vocal labour, thought and skill that goes into their art.

Nirmala Devi measured up on every yardstick. And the song that I can never get out of my head is the gloriously rendered chaiti, Yehi thaiyan motiya herai gayli, Rama. A chaiti is a summer song–of koyal, heat, long empty days and distant rains. And its give away is the ‘ho Rama’ appended to the song, a signifier of deep feeling. Of all that I have heard–and they are all exquisite–this one is the most delectable, as the nayika complains of losing her pearl earring, dropped no doubt in the midst of some nok jhonk with her lover.

Nirmala Devi’s life is deeply intriguing, how she landed up in Mumbai, became a part of the film industry and finally faded away, her art not acknowledged often or well enough. There are some treasures recorded to Doordarshan like this great ghazal. Here was one star mother whose own star power outshines her son’s–or so I believe.

Malini Nair

Slowmaxxing Love On The Screen

I found The New Years right before this new year. This Spanish series might be the most romantic thing I’ve seen in half a decade. You know the kind of romance that releases slowly, in its pleasure and its pain, demanding patience and gentle grace. So I stayed with the lovers, with Anna and Óscar, whose (love?) story is told through the window of a decade. These are friends you get to meet only once a year, at the end (and the beginning). Major milestones have happened off screen but we quickly catch up, sometimes at parties and family dinners, over grape-gulping rituals and resolutions, even through breakups and pandemics.

I missed being in the cinematic company of love. Romance has died on the screen, for many reasons dissected over and over, and I’m here to indulge this nostalgia and joy of watching a good love story unfold, unhurried, through streams of conversations and stretches of silence. Monologues about trauma, arguments about nothing and everything; words laced with love and disappointment and hate sometimes. But words nonetheless, the only tool the lovers have to understand and show parts of themselves.

It resembles, variably, Richard Linklater’s charm, Wim Wenders’ grace, even Payal Kapadia’s genius. That silliness and awkwardness, action and stillness, contained in time and space that follow a logic of their own. Time in this show is sometimes confined to four hours or two days, and sometimes it flows for 365 days and ten years. It resists the crawl of the clock but instead shows up on the lovers’ faces, in their touch, through their gaze. Their love lives in time, to make people like you and me live outside of it. Timeless, this rhythm of romance.

The eras of frictionmaxxing and slowmaxxing are upon us—words that tell us with urgency to return to a more human way to live, learn, and love. Romance, which defies the confines of time and indulges the friction of communication and relationship, feels like a refuge for the living, showing what is interesting and essential about us.

If there were a compendium for these treatises essential to modern life, I would inscribe these words from a Modern Love essay, which apply not just to Anna and Óscar but to all of us. “It doesn’t matter what time it is. Think in months, years…Someone loves you, where are you going? There are some things you will never do, it doesn’t matter, there’s no rush.” There’s no rush.

Saumya Kalia

Poetry in a Time of Violence

As 2025 came to an end, I feel the absence of poetry in our lives. Not just in our reading or how we approach the world but also in the way we make sense of it. Every year feels heavy with violence and struggle whether it is the brazen imperialist US attack on Venezuela, the ICE raids, the exploitation of gig work, or the fate of Indian political prisoners. Along with the news, my mind jumps from one tragedy to another till it feels drained.

I wish to be closer to poetry again. At the start of this year, I went back to Marathi poetry, to Dekhani by Bhalchandra Nemade, who is both a novelist and a poet. His novels carry poetry, and his poems carry stories. In Dekhani, he writes of labour, grief, toil and people in their everyday lives. I return to it when things are too hard to comprehend, when hopelessness takes over. I also picked up Parivrajak by Gautamiputra Kamble. In a lucky, heartfelt happenstance it was on December 6, Mahaparinirvan Divas. I am reading Kamble’s story in Marathi, and it feels alive in its roots in everyday life. It is fiction but so deeply connected to the real world: it is about making your own path, about seeing the world as it is, about rituals followed blindly, and about the search for the unknown. The English translation, The Seeker, has been published by Blaft Publications.

I also held onto poems like The Rungs by Benjamin Gucciardi and Blue by Sasha taqwšəblu LaPointe. I also watched Paterson and Perfect Days. I wait for more introspection, for less mindless scrolling and more staying with a poem instead of jumping from one internet discourse to another.

Urvi Sawant

Want to explore more newsletters? Our weekly digest Behanvox and monthly Postscript invite you, the reader, into our newsroom to understand how the stories you read came to be – from ideation to execution. Subscribe here or visit our Substack channel for more.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.