In The Age Of AI, The Promise Of A Feminist Internet

A digital rights activist talks about the history of the Indian internet, the possibility of feminist AI regulations, and how we can centre the right to pleasure

Once, the internet was a place of discovery. You logged in to find others like you: messy fan pages, personal blogs, queer communities, labours of love. Now, 40 to 60% of those links no longer exist. Five profit-driven companies own most of what we see and AI-generated content drowns spaces.

“We are made to forget that the internet wasn’t always like this,” says Smita, who works on gender, sexuality, and internet rights at the Association for Progressive Communications. For instance, the internet was always queer and feminist but has yielded to a grey homogeneity. AI slop floods digital spaces, and government policies have tethered us to online spaces that code dependence, exclusion, and repression. “We have not meaningfully consented to this internet,” Smita adds.

What does it mean to reclaim the internet as a feminist space centering care, joy, and the right to be offline? In a conversation with Saumya Kalia, Smita talks about the history of the Indian internet, the possibility of feminist AI regulations, and why pleasure should be centred in digital rights conversations. Edited excerpts below:

What can be characterised as a feminist internet?

At the core of it, a feminist internet is a space that offers meaningful access – not just accessibility for persons with disability but also access in terms of language, for people with different degrees of digital literacy and familiarity with technology. It is access to information that is not programmed but has multiple viewpoints and dimensions to it.

An internet will only be feminist if it’s not just equal but also equitable. We need a space where there are provisions made to ensure the internet works for people who are at the absolute margins, who are not included in conversations. Unless the internet is equitable, it will not become the level playing field that everyone hopes that it will be. And then ultimately, a feminist internet is an internet for fun, to meet people and have community.

Tell us about the early conversations around a ‘feminist internet’.

My Master’s thesis looked at how lesbian and bisexual women used dating websites as a space to form communities, so it seemed like a direct segue into talking about sexuality, gender and technology. Later, as part of Point of View [a non-profit working on gender and sexual expression], we built curriculums on teaching digital rights and digital security with a feminist, intersectional lens. Usually when cyber security people parachute in, they don’t really see what the community needs – they impose whatever technology they think is right and leave. But it’s not helpful, especially for communities where English is not the first language; if something is inaccessible, people leave it.

The Association for Progressive Communication later in 2014 and 2015 did consultations with 50 activists and academicians from different movements – feminism, LGBTQI rights, digital rights, child rights – along with feminist techies most of whom were from Global South countries, and came up with what was called the feminist principles of the internet. It almost sounds fantastical if you look at these principles and then look at the internet today. But for a lot of people, it was the first time they had a guide on thinking about a feminist internet. It’s idealistic but we encourage different communities to take different things out of it. Say someone looking at freedom of assembly or association could talk about its implications online.

It’s almost like designing a virtual city.

Very much so. Though the internet feels virtual, it’s a reflection of the life we lead outside. So it would be a safe city, but it would be a ‘non smart’ safe city – in that it should not be reliant on surveillance for security but rather the design should be secured by virtue of including people from diverse backgrounds from the very beginning. It’s a subtle but important difference.

What feminist principles has India looked at or should be focusing on?

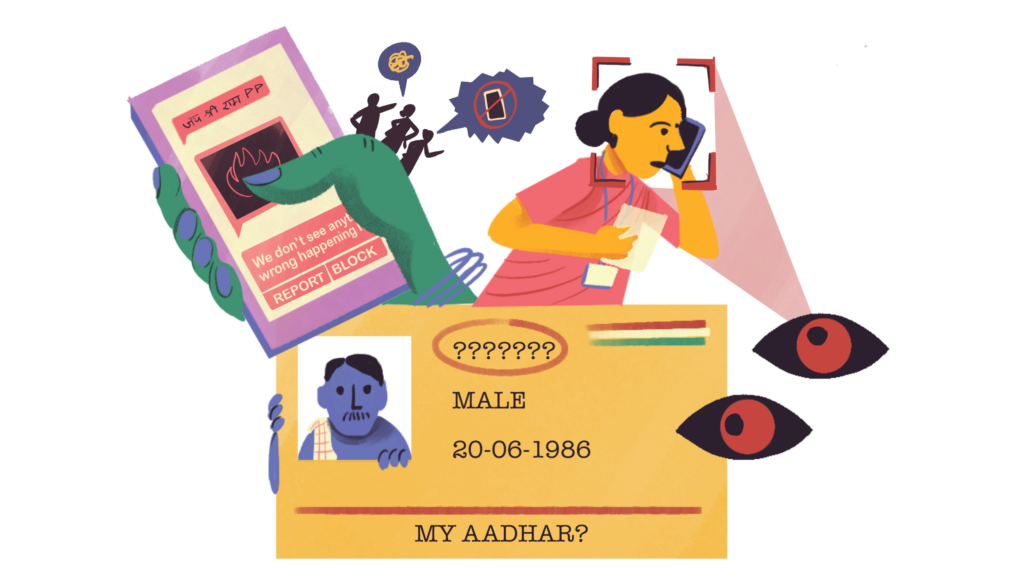

All of it. India is falling behind in the digital rights space. There’s no index which looks at digital rights particularly but other metrics are telling, like India’s ranking on the Press Freedom Index or the number of government-ordered internet shutdowns. India has one of the highest government requests to Google to take down content. Everything that can be done badly is being done. One of the most horrendous examples is compulsorily pushing people online, which violates one of the most important feminist principles, that you need the right to be offline as well as online. During the pandemic, everyone was forced to get an Aadhaar card for Covid vaccine registration. Recently they have implemented a facial recognition system and an OTP for procuring ration. This is problematic – facial ID is a racist technology, it doesn’t read people (especially people of colour and non-men) properly. What also happens is that the OTP goes to the husband’s mobile, whereas the woman is the one who has come to collect the ration, and she’s unable to take it home. Before this, they had mandated fingerprints when Aadhaar was big but that also didn’t work.

Your basic survival necessity should not be connected to the internet, especially in a country like India where internet penetration is highly gendered and much more complicated to measure than a simple percentage.

What do we mean by a ‘right to be offline’, and what does its denial entail?

I would articulate it like this: if you need a smartphone and an internet connection to get basic facilities like water, access to healthcare, access to vaccines, safety – or basic necessities like roti, kapda, makaan – then you do not have the right to be offline. If a shopkeeper can only give you ration through an online system that scans your fingerprint or your face, you’re being forced to go online.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of consent. During the pandemic, people were forced to buy a mobile phone with money they didn’t have to get regular updates from the government – they were not consenting to being online. For trans women based in small towns in Tamil Nadu, for example, the only way they could get information was when a tempo with a loudspeaker would make announcements about the lockdown, timing of shops, availability of doctors, medical precautions. They couldn’t recharge their phones because the mobile shops were shut. If the government forces the internet to a degree that it’s the only source of information, can you really say the internet is a free space and the government cares for its people?

And if the government insists on pushing people online, they have to build infrastructure to that degree, which is where India differs from other countries. Take IRCTC or the postal tracking website, before you can find the little box for tracking your parcel, you have to click 10 times and scroll past the Prime Minister’s face for five pages. Even with PM Cares and the Covid apps, there was no transparency about where the data is being stored, how long it is going to be stored for, who has access to it, whether the database is secure. When your infrastructure is not up to the mark, what are you forcing people into?

[The Union Government recently notified the Digital Personal Data Protection Act. Activists believe the privacy laws are opaque, undermine informed consent, and perpetuate “information asymmetry between individuals and large platforms”.]

What were the key moments in how Indians experienced the early days of the internet?

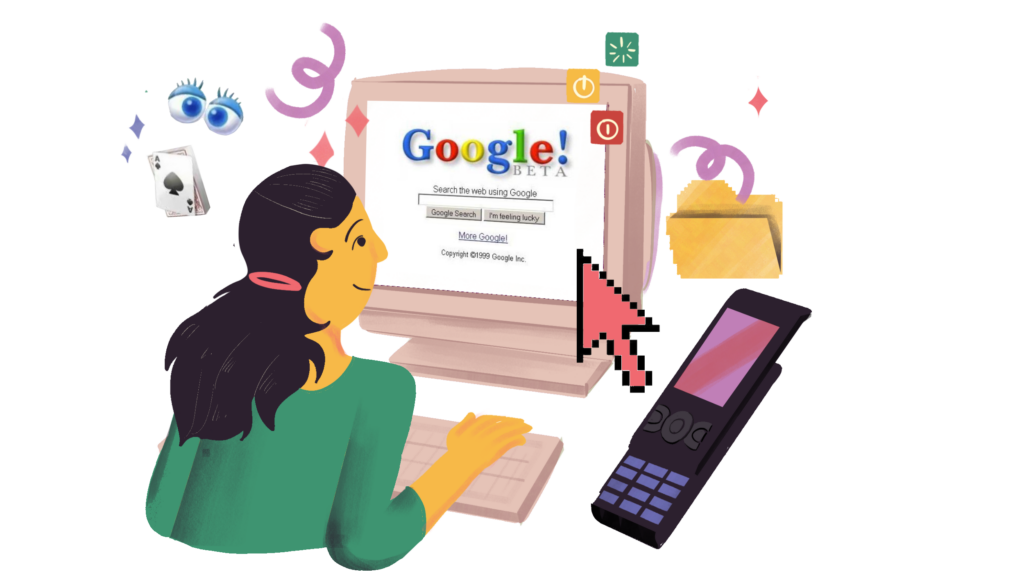

In India, people flocked to the internet when internet cafes became a thing. Broadband providers like Sify had cyber cafes everywhere but were immediately taken over by men who wanted to watch porn there. There is nothing wrong with that except watching it in a public space creates discomfort and contributes to a lack of safety, so women and young people couldn’t really access the internet beyond a certain time.

The biggest surge happened when smartphones came up – it was a turning point in terms of access; between 2015 and 2019, cheaper phones, affordable data plans and more operators led to a mobile internet usage boom and more people went online. It was much more affordable than a computer, and even now, most people don’t have laptops or a PC. Demonetisation was another subtle but big jump. After that many other schemes went online because [the government] thought enough people had the internet, which data shows they don’t. And then the next big surge would be Covid.

These small spikes have been there but the instances of online gender-based violence unfortunately are present as early as the 2000s. The first big ‘scandal’ was the Mysore Mallige – when a college-going couple filmed themselves having sex, and the video was leaked by a friend of the man in the video. And after that, there was the DPS MMS scandal in 2004 which became very big and had very gendered consequences. The boy missed a cricket match but the girl had to leave the school and the country. But I think the reason why people keep defying and going back to the internet, is because there is pleasure in there, there is connection, there is community.

The internet was also a tool for building movements such as the SaveRTI and Pink Chaddi campaigns. Has that changed with the prominence of Big Tech companies?

One of the reasons why governments and private sector are trying so hard to control what people are seeing and doing, or why internet shutdowns have become so prevalent, is because it played such a big role in so many social movements, not just in India but across the world — from the Arab spring and the MeToo movement to the recent Nepal uprising.

The internet has helped in informing and educating people, a better-informed population will also protest when the government is not doing what it’s supposed to do. It has also played a role in bringing together a critical mass of people. Before the internet I could go to Azad Maidan and see what’s happening there, but that’s not the world we live in today. The CAA-NRC protests were another pivotal moment also because the internet was used to build knowledge.

In a lot of countries, the moment a protest erupted was when the governments touched mobile phones. For example, in Lebanon, it was when they decided to charge for video calls on WhatsApp; in Malawi, it was because they decided to increase mobile data charges; in Nepal, they decided to ban social media, which, combined with massive growing dissatisfaction and economic disparity. India has not outrightly banned anything – banning is what causes people to protest – but it has insidiously changed laws to increase control and surveillance, and that’s why people notice slowly. The Income Tax Department this year said that very soon it will have access to our messages and social media. What is the logic? It’s a way to increase control online. And it also shows ways the government misuses the internet. In the Bhima Koregaon case, evidence was planted on activist phones using a WhatsApp link. Pegasus spyware was used to hack phones of politicians, journalists, activists, judges; it should have been a huge issue but there was barely a whimper.

Could a Pink Chaddi-like campaign happen today, in this media ecosystem?

I worry about the corporate control and the government control, and there’s a collusion between them, but more than that, it would be the widespread biases online and offline.

There’s a way to create visibility, even with corporate control, like Nepal showed us recently. The social media and the internet intermediaries were never on the people’s side; it so happened that people figured out how to hack their spaces for desired needs. Facebook never wanted lesbians from Chennai to form a group secretly on Facebook and then meet in person, but it happened because people hacked the system. People can figure it out, but the reality is that prejudice, populism and Islamophobia in the offline world completely permeate online as well.

For marginalised communities, the internet is both a space for self assertion and of witnessing violence. At least 13% of hate posts on Facebook are related to caste-based hate speech, one 2024 study showed. How have these two dynamics of self-assertion and safety played out?

Whatever prejudices exist offline, they translate online and it just changes form. Recently, a Dalit man was beaten up because he posted a Facebook profile picture in which he had a polished, turned up moustache. The other side of the coin is when Kavin Selvaganesh [a young Dalit engineer] was murdered for being in a relationship with a dominant caste woman, his murder and murderer were celebrated online. Like our lives, prejudices flow both ways online and offline.

In many ways, this particular balance that has to be struck is very similar to what happens in the physical world. If you’re visible about certain issues or as certain kinds of people, there will be violence and the internet mirrors the offline world in this aspect. Whenever there is a documentation of joy of people who are Dalit, there is a repercussion. The good thing is that the Internet also creates space and reach that was previously not possible. The risk of online trolling is ever present but there are ways to protect yourself and get support that one could not gather in a physical world.

When it came out, the internet was seen as this space that will be a leveling ground for marginalised people – for Dalit people, women, queer and trans people, Black people, all of us. That’s also why it got regulated very quickly. The people who created the internet, who are probably white, cis, straight men in global North countries, moved to contain it the moment it challenged their power. They can’t shut it down because it makes them money, so they take to regulations and create more divisions online.

The internet challenges the status quo as it is, and the feminist internet all the more so. I always feel like the Internet has always been a little queer and feminist but somewhere along the line we were made to forget that and it has been taken over. The inventor of the Web very intentionally did not patent it, there’s a reason for that.

What is your first memory of experiencing the internet, and finding pleasure?

There are many. I love the internet. I love computers. I grew up in the UAE, I got a computer, one of those big ones, in the second standard. And the internet was very expensive at that point. I would go play on Neopets, this website where you can have virtual pets. It was a really silly thing, but so much fun.

Because I was queer, the internet was also kind of my life, it’s what kept me sane for a long time. When you grow up in a country like UAE, where even the mention of the word is banned, you start to think you’re going crazy, maybe this is not how you should feel about your women friends, but the internet in many ways showed me I’m not alone.

After I came to India for my undergraduation, I joined dating websites. I didn’t even want to date, I just wanted to talk to people, and that was wonderful, because I met some really nice people there. I have always been nerdy, so finding websites which spoke to specific interests was always exciting – like okay, there are other people doing this.

What did the internet look like then? Messy website, chaotic?

Terrible fonts.

What happened to the design then?

I think the world is homogenised in terms of design today, and it’s inevitable that it also goes online. If you look at Instagram, everything is plain and white and beige, so boring. There’s a theory that when design goes minimalist, it’s also an indicator of fascism. The white walls design in a museum was appropriated by and popularised during the Nazi regime — they started using it because white symbolised purity. They wanted to sanitise how art is supposed to be seen, and also wanted to control whose art is shown.

Everything about cyber security and the internet is about safety and violence. Why don’t we think of the internet as a space of joy?

It’s for multiple reasons. At its core, it’s patriarchy. Before Covid when I was at PoV, we worked with young women and LGBTQ+ persons from different communities, and found young women are often the last ones to get a phone in their households, and even when they get a phone, it’s highly surveilled. The worry is always: who is she talking to, is he from our religion, our caste, is he a Muslim? Families don’t even think about women talking to other women, that’s a very far off concept. This surveillance shows that the immediate worry is that whatever freedom is not afforded to women in the physical world, the phone will become a way to access that. So if you push for digital rights, which is joyful and pleasurable, you will have to accept that your daughters can use a phone for things other than classes or college applications or work. And that’s a very difficult thing for Indians to accept.

Globally, everyone knows there’s actually a lot of work to be done around gender, but if you go anywhere, from the Internet Governance Forum [a United Nations-convened group including governments, civil society, and companies to discuss all things internet and ethical AI] to a UNDP consultation, it starts and stops at online gender-based violence. It’s about how women are attacked, how they are abused – all of which is true – but that’s not why we are online. That’s not why we are fighting for space.

The internet is a place of violence but it’s not the only place where violence happens. What makes online violence feel exceptional and pervasive is there is no accountability and no consequences; it is not really seen as violence. There are also no regulatory mechanisms on social media platforms to handle this in a meaningful way.

Before AI, we poured money into smart cities. This approach to think of tech as a silver bullet has always been there. After the Delhi 2012 rape case, government agencies launched some 70-80 apps on women’s safety, but all of them worked on either geo fencing – if you go beyond a certain point it will send SOS messages – or you could click a button and send information. Both had to do with surveillance. But the app is not going to keep you safe until you change actual policing on ground, put street lights in an area, and challenge social norms.

What is the cost of neglecting these affective elements of our online lives, say the right to pleasure, within the digital rights movements?

Digital rights are already sidelined and when you create hierarchies, some people will never get their turn. The TikTok ban in India is an example of this. TikTok was used primarily by those from poorer communities for pleasure. Daily wage workers – say, brick layers, construction workers, people making utensils – were posting videos of dancing, of teaching English and more. Instagram was too sanitised; Tiktok was free and easy. That was a really rich time for people to document their lives and create their own videos and have fun. I’m not saying that short form content is good or there are no data concerns, but it gave people freedom.

TikTok is also a tool of political expression – in many countries, including the US recently, it gets banned when there is a lot of political activity online. When it got banned in India, there was barely any protest. Imagine if Twitter were banned today – people and parliamentarians would call it an attack on freedom of expression. Why is the right to be on TikTok not seen as the same? There are caste and gender implications there.

The government recently released the AI Governance Guidelines ahead of the India AI Summit. Can AI regulation happen in a feminist way, and what should India be looking at?

Firstly, we shouldn’t be holding it in India. The current government and its policies have made enemies out of our neighbours. People from Pakistan can practically not get a visa, same for those from Afghanistan and Bangladesh. India stopped visa-free entry for Myanmar passport holders, and the Rohingya people in particular are unlawfully detained and deported.

If half of our neighbours cannot come in easily, what is feminist about [this summit]?

Also, I don’t think it’s possible to imagine a feminist AI – at the core of it, it’s an exploitative technology. The question of regulation is complicated, it has to be done on multiple levels. First, we need to regulate disinformation. How do we hold anyone accountable when platforms aren’t accountable? Regulating AI has to include regulating hate speech, online gender-based violence, and deepfakes. So policymakers may have to look at a broad framing, that AI should not be used to harm or infringe on rights. But it can’t be so broad that it is abused and becomes a tool for censorship. If we leave it to the Indian government, they will try to do what they tried with the obscenity law and anything involving digital laws – they would go with a Victorian mentality, and now a Hindutva approach as well.

The harder question is what are we regulating. Its use? Its creation? Its impact? Are we talking about server location, consent in data collection, or whether an AI model can be course-corrected while it’s being trained? And how do we ensure the training data is actually diverse, when lack of diversity is the starting problem? Regulation is still far away because you need to ask these questions to understand what you need to regulate. As with other regulations, it could further sideline the conversation on the internet as a space of joy and pleasure.

(One recommendation in the AI governance guidelines pushes for the “use of locally relevant datasets to support the creation of culturally representative models and applications”.)

How can we improve Instagram or Facebook as a feminist space for pleasure?

Firstly, they need to un-black box their reporting mechanisms. They need to tell us how when you report violence that’s happening, how it is actually being addressed. They need to increase moderators on these platforms, which they have cut further. And they need to stop AI moderation, that’s a recipe for disaster.

They need to work on the design to make it more people-centric rather than profit-centric. Like stop the infinity scroll. And Instagram knows how to do this — it was like this before, so go back to that. Go back to a chronological timeline, showing posts from the people who you actually follow, and not the retweeted random posts. Make it more accessible in terms of how you post, and reduce AI (including AI-generated video content).

One thing we could push for immediately is to ask platforms for proper AI labelling. If a content is AI-generated or it has used AI at any part of the video, it needs to be labeled. Instagram has a ‘made with AI’ tag but there’s nothing regulating it. Clear labelling will help check information pollution – you will know if something is misinformation or disinformation immediately. And it would help social media companies too: the industry is training its own models on AI slop, which is rubbish, so if you do this labelling properly companies will be able to create better AI products. Even for purely capitalist reasons, companies should do this; people are very unhappy with having to ask, every minute they are online, if something is real or AI.

What is an example of a feminist internet in practice in India?

It can be on Instagram or anywhere, but there are pockets where people try to create spaces which are queer and feminist. During the pandemic, a bunch of non-binary trans people who were stuck at home – which are violence spaces – created a group on Instagram where they would send photos of themselves as they present and appreciate each other from there. This queer organisation in Manipur used WhatsApp and those small phones to get deliveries in person to people who needed HIV medication and hormone therapy. It was beautiful, and so necessary.

I don’t believe that you have to leave everything, go to the perfect platform or the perfect technology – it’s impossible. We don’t have the money, we don’t have the skills. Fediverse [a decentralised, more democratic way of social networking] is an aspiration, but it’s currently very inaccessible to a lot of people here.

It’s almost like it’s not about the digital space, but what people make of it and how they use it which makes it a feminist internet.

Precisely. I don’t think the internet is inherently bad. It’s just become highly capitalist, and people are not intentional in how they use it. Earlier with a modem, you had to be intentional because it costs money, but now you don’t have the intentionality partly due to how platforms are designed.

Like with the physical world, the online world also needs intentionality.

When we are out in public, a lot of us don’t wander aimlessly, it’s with some sort of purpose. I want to go for a walk in my neighborhood at this time because the weather is nice. I want to go to a park. Or I want a chai. Online, you sit and suddenly you’re scrolling on Instagram. It’s the equivalent of ‘oh I’m standing here might as well go walk down the road’. If we don’t do that in the offline world, why do we do that online?

That is why the right to be offline matters. Platforms and governments make it harder and harder to be offline. If you feel like you need the phone to travel, eat food, get a train ticket, how will you not live on it? And when this has been enforced so much, it’s very hard to be intentional on the more frivolous, joyful corners of the internet.

But pleasure comes back when you broaden your language and idea of technology. Remember Walkmans? It’s technology. Your paintbrush, a good pen. Silly games that you play, Tamagotchi, it’s all technology and it’s all pleasure. That’s why we started going into phones – remember the snakes game? We forget these things sometimes and lose joy in the process also.

Behans, what are your early memories of the internet? What brought you joy, and where do you find pleasure now? Write to us at contact@behanbox.com.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.