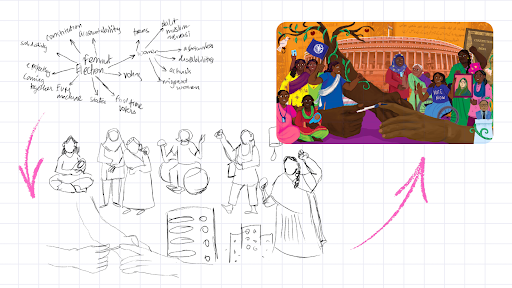

Sometimes I sit with my sketchbook and wonder: what even is a feminist visual? Drawing someone else’s life feels like a responsibility I am still learning to carry. How do you make ‘care’ visible? Or solidarity? Or the many ways in which people resist and rebuild the world?

At BehanBox, every story begins long before I put pencil to paper. It starts in editorial meetings, where we talk about the stories we want to tell. Reporters return from their fieldwork with truths on the ground and bare it all. We dissect them, find gaps, understand the bits that don’t fit the puzzle and ask the big questions: Who is unheard and invisible? Who is harmed? Who must be held accountable? These discussions become the foundation for my illustrations.

People often think illustration is solitary work, but in reality, everything I draw is stitched from the labour of the journalists who go out, listen, observe, hold someone’s story with patience, and bring it back so I can make sense of it visually.

I remember a meeting when I kept returning to the same visual trope of women with raised fists, to show dissent, one of our team members looked at my sketch and gently asked, “Can you think of other ways in which women resist daily?” This question has followed me everywhere in my art. Since then, I’ve tried to notice many nuances of women’s lives that escape mainstream thought and discussion and hence representation. For instance, care that sustains movements or the everyday negotiations women make while navigating patriarchy.

Along the way I’ve had small revelations and plenty of mistakes. While drawing a sketch, I often keep thinking: How do I draw anger without softening it? How do I show aspiration alongside struggle? How do I avoid easy shortcuts when illustrating a story about technology? How do I depict the lives of Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim women, gender diverse persons, women with disabilities, ASHA workers– people who are rarely recognised as knowledge holders and public intellectuals?

Every choice in a sketch matters – from the skin tone, the expressions to the body type, so that the people I draw feel real, rooted, and powerful. These are women with swag who negotiate their lives with grit even though the structures fail them.

Much of what I do comes from the artists and storytellers I’ve learned from and been inspired by – anti-caste artists like Shrujana, Bigfatbao, Vikrant Bhise, and many more who are actively doing this work today. The art and visual journalism of Sanitary Panels and Green Humour are also constant sources of inspiration for me.

If I were to describe my process in the simplest terms, here is how it goes. First, I try to understand the people in the story and the structures they are framed by: policies, law, data, and power. Then I think about the purpose of the illustration. What do I want the audience to feel? How do I want them to act? Like a magpie, I collect all the interesting pieces that stay with me after reading the story – anecdotes from activists, fragments of quotes, photos from the field. And finally, I start sketching, letting the pieces find their own rhythm until a visual language begins to emerge.