It is not that informal, contractual work is new to India. We have reported repeatedly on it and how it disproportionately affects women across sectors (here, here and here.) What has changed over the last few years, and certainly since the pandemic, is that factory floors have found a digital avatar – app networks.

Aggregator companies present themselves as digital market places where workers are “independent” agents, says union activists and labour rights scholars, but they function more like a single, centralised employer, a modern-day mill. Workers rely on these platforms for livelihoods, follow strict controls and supervisions, and spend most of their day performing tasks assigned by the app – four conditions Indian courts have previously used to establish an employer-employee relationship in informal work.

In an insightful and exhaustively researched analysis this week, Saumya Kalia explains why it is hard for unions to forge solidarity in platform companies that employ millions of scattered workers whose paths criss-cross in an increasingly fragmented and alienating digital economy. Despite this, dozens of emerging unions and informal collectives are working hard at bringing awareness of the exploitative practices that are rife in these spaces. We have reported extensively on how this economy, beneath its veneer of being faceless, flexible and worker friendly, can actually be intimidating and coercive.

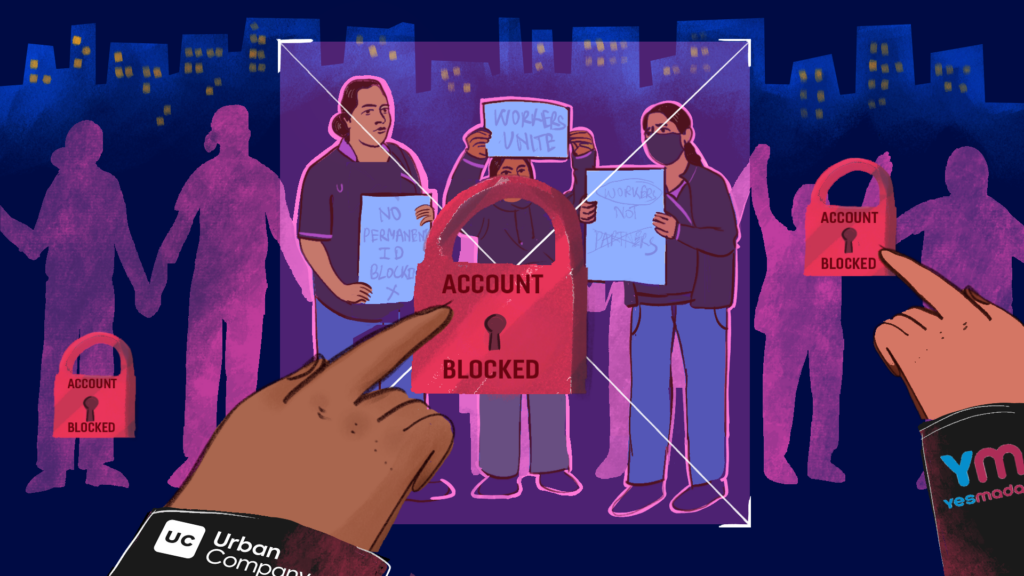

But indefatigable collectives and unions are still working at making a difference. Nisha Pawar’s phone is a hive of activity. Her practised fingers dart across the screen, flipping between multiple WhatsApp groups bringing messages from women working as beauticians and spa therapists on platforms like Urban Company and Yes Madam. There are also missed calls, voice notes, SOS messages, and meeting schedules.

On quieter days, Nisha, a leader at the Gig and Platform Service Workers’ Union (GIPSWU) in Maharashtra, acts as an administrator, accompanying complainants to the police station or labour commissioner’s office to file their grievance. At other times she’s a leader, explaining to women how commission slabs erode earnings and the strength of a collective or listening to their challenges. Graver days bring news of a suicide or death, and then she plays investigator, digging up medical records, tracking down family members, gathering evidence to establish that when a worker dies on the job, the platform must be held accountable.

There’s always fear. In the last three years, alleges Nisha, Urban Company’s management has infiltrated these WhatsApp groups and blocked accounts of ‘partners’ found to be a part of unions. “The company wants to surveil every decision we make, every conversation we have, so that they can retaliate and dismantle efforts to build our union,” Nisha says. “We keep motivating the workers, easing their fears. We have to show them they are not alone.”

This is the first of a two-part series on efforts to unionise platform workers. The next will reflect on why gender is an even bigger barrier to solidarity in this sector.

Read the story here.