Why Unions Find It Hard To Forge Worker Solidarity In Platform Companies

In the platform economy, time is scarce, worker interactions are discouraged, and protests met with punishment. The idea of both union and unity are threatened

Nisha Pawar’s phone is a hive of activity. Her practised fingers dart across the screen, flipping between multiple WhatsApp groups bringing messages from women working as beauticians and spa therapists on platforms like Urban Company and Yes Madam. There are also missed calls, voice notes, SOS messages, and meeting schedules.

On quieter days, Nisha, a leader at the Gig and Platform Service Workers’ Union (GIPSWU) in Maharashtra, acts as an administrator, accompanying complainants to the police station or labour commissioner’s office to file their grievance. At other times she’s a leader, explaining to women how commission slabs erode earnings and the strength of a collective or listening to their challenges. Graver days bring news of a suicide or death, and then she plays investigator, digging up medical records, tracking down family members, gathering evidence to establish that when a worker dies on the job, the platform must be held accountable.

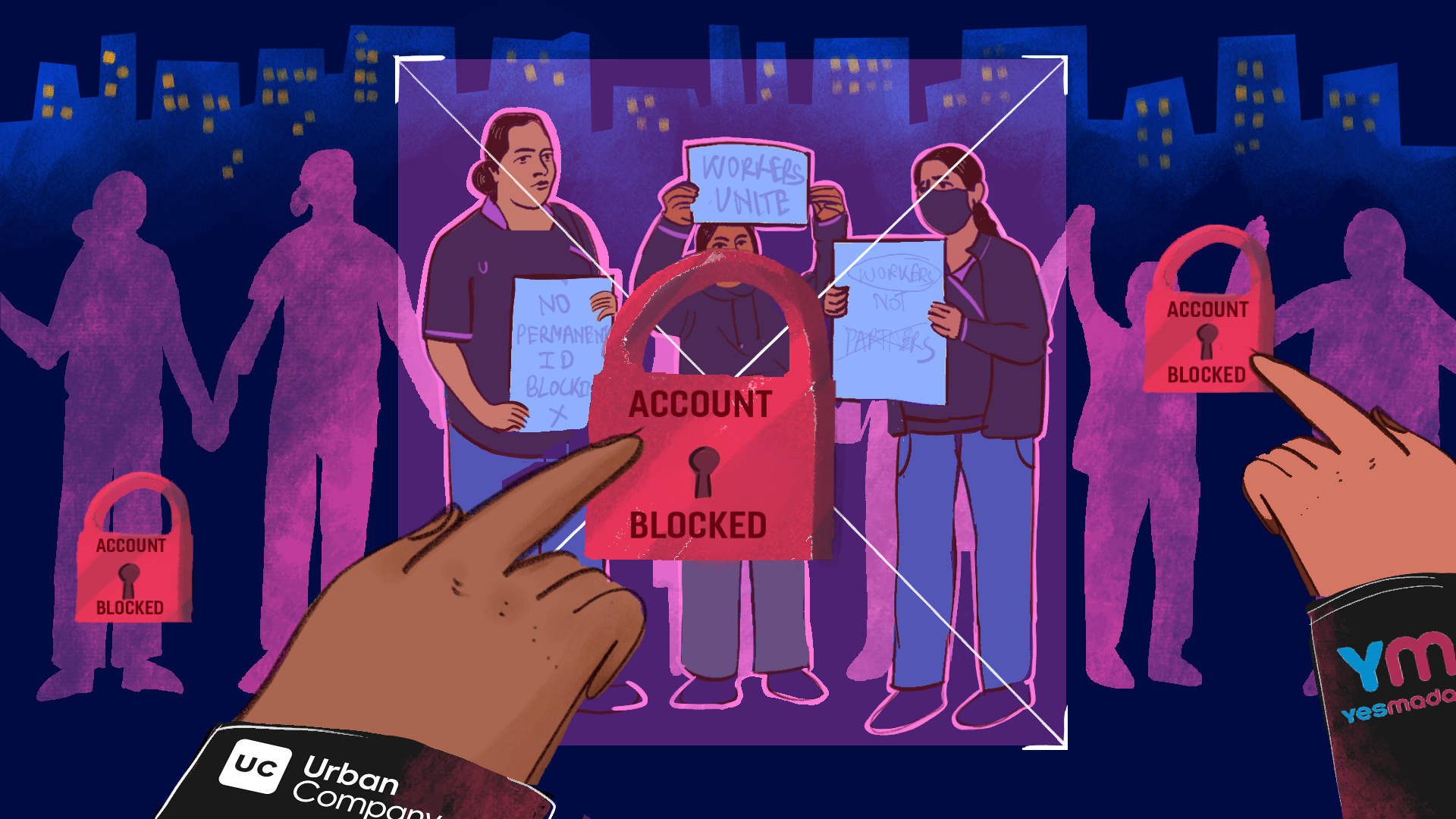

There’s always fear. In the last three years, alleges Nisha, Urban Company’s management has infiltrated these WhatsApp groups and blocked accounts of ‘partners’ found to be a part of unions. “The company wants to surveil every decision we make, every conversation we have, so that they can retaliate and dismantle efforts to build our union,” Nisha says. “We keep motivating the workers, easing their fears. We have to show them they are not alone.”

GIPSWU is one among the dozens of emerging unions and informal collectives supporting millions of scattered workers whose paths criss-cross in an increasingly fragmented and alienating digital economy. How do you build solidarity when there’s no physical workplace or time frame, when algorithms measure the worker’s worth each day, and where everyone is easily replaceable? Where can workers go when customers misbehave, algorithms dictate earnings, and companies block IDs? Should there be separate legislation for gig workers or should they be incorporated into existing labour laws?

In March, the International Trade Union Confederation called for the right to organise for all platform workers. A joint declaration by 33 groups urged the International Labour Conference to adopt a convention safeguarding their collective bargaining rights.

In India, platform companies do not recognise worker collectives or unions, per a Fairworks study, and India’s laws leave workers unambiguously defined and outside the scope of legislations such as the Trade Union Act, 1926. India’s cost of living crisis, high unemployment rate among young people, and the scattered nature of digital work gave platforms outsized power to control and repress workers, activists and experts told BehanBox.

“That’s why unions matter,” says Rikta Krishnaswamy, an organiser with Rajdhani App-Based Workers Union (formerly AIGWU). “We are in a neoliberal age, and with the weakening of the trade union movement, the platforms are shaping the dominant story – that this is flexible work, with lower entry barriers, and full independence. But none of this is true, the lived experience of workers contradicts these claims. We need class and caste organising, and for workers to build these movements to change the narrative.”

In a two-part series, we explore the unique challenges union activists face in creating worker solidarity in platform companies. In this, the first part, we look at the logistical, ideological, and also existential issues. Next, we will examine how gender complicated the challenge even further.

‘Modern-Day, Digital Mills’

Workers have two fights on their hands – one for daily survival, and the other for long-term rights – while unions move between the two, says Ritika.

Manju, a leader at GIPSWU, begins her day at the union office where workers stream in to report problems – blocked IDs, opaque policies, arbitrary pay cuts, customer abuse, sexual harassment. “I try to be present most times so that I can meet them and register their case,” she says. Other times she meets workers closer to their station hubs.

Manju points out the advantage of a collective body – it can talk to companies, labour commissioners, the National Human Rights Commission – things a single worker cannot do. “When we escalate an issue and [for instance] get an ID unblocked, the workers see that unions are effective. That trust helps,” she says.

Union work rises and falls with the rhythms of workers’ lives. On slow days, they conduct drives on making workers aware about government schemes and plan how to mobilise new groups. “It is hard to mobilise people – they are always in a rush,” Manju says. “We show up at their working points directly and then tell them about meetings. If we try to mobilise 200 people, at least 50 show up.” Sometimes workers turn off their digital IDs to show up to meetings – they say hamare haq ki baat ho rahi hai. (it is our rights that are being discussed).

In gig work companies, workers are labelled “partners”, “independent agents”, “contractors”, a misclassification that strips them of labour rights. Manju tells people about what rights exist on paper and what are missing. “Ab unko ehsaas ho gaya hai ki ab hum kya hain, kaun hain (they are more aware of their identity as gig workers),” she says.

Karnataka, last month, passed a historic legislation to ensure the rights of gig workers and hold platforms or aggregator companies accountable for workers’ occupational health and safety. News of gig worker legislations proposed in states like Rajasthan and Telangana gives workers the hope that one day there may be similar laws for the entire country. Similar discussions are underway in Jharkhand and Maharashtra.

Informal, contractual work has always existed in India, but app networks are the new factory floors. Aggregator companies present themselves as digital market places, where workers are independent agents, but Rikta says they function more like a single, centralised employer, a modern-day mill. Workers rely on these platforms for livelihoods, follow strict controls and supervisions, and spend most of their day performing tasks assigned by the app – four conditions Indian courts have previously used to establish an employer-employee relationship in informal work.

“Our agenda is to tell the workers this is the same work but in a new form, to go to them and map the long fight – and show how small demands and scattered strikes can scale into a larger movement,” she says.

In GIPSWU meetings, discussions shuffle between learning little tricks of the trade, an attempt to negotiate fairer commission or reduced penalties, and how to listen. “A lot of times women don’t speak up against violence. So it is important to hear them no matter how tenable a solution is,” says Manju. Women who go unheard by their families, communities and employers are particularly vulnerable.

“Imagine the cognitive dissonance of an Urban Company worker,” Rikta says. “They’re highly skilled, experienced, called a business partner, and then they’re treated like shit in every aspect of the way.” The union is a space where these contradictions are acknowledged.

A Young, Unique Movement

The unionising landscape is bustling – some like Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (TGPWU) are as new as the platform economy; others like the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC) predate the independence movement. At least 18 collectives are organising across different sectors like transport, delivery, and home-based work.

The Covid epidemic was a catalyst for this burst of union activity, activists say. In the early 2010s, disruptor transport platforms like Ola and Uber had emerged, riding the idyllic wave of digitisation and flexible work arrangements for workers. “It took three-four years for workers to get out of that honeymoon period,” says Aditya Ray, an urban studies and gig work scholar.

TGPWU’s founder Shaik Salauddin led some of the first protests – over worker deaths, exploitative commissions, and the disappointment of drivers who had migrated from traditional cab services.

The collapsing, post-pandemic job market pushed people onto platform work, and the demand for services such as delivery and cleaning saw an uptick. At the same time, those already in this sector felt stifled by unfair pay reductions, unreasonable work hours, and client harassment. This was also the time when the Bharatiya Janata Party-led central government introduced four new contentious labour codes covering wages, industrial disputes, social security, and occupational safety and health. Ambiguous on the definition of a “gig worker”, they excluded millions from social security protections.

As workers buoyed up to protest, platforms got better at suppressing them – union workers speak of blocked IDs, unfair terminations, FIRs, and union busting tactics. “Platforms became more powerful and started showing their real faces after Covid-19,” says Nisha.

The result is a “unique” trajectory of platform unionism, noted Aju John and Aditya Ray in this paper. It closely mirrors that of construction workers’ struggles – beginning with demands for formal recognition, then negotiating strategic compromises for welfare through dedicated legislation.

While participation in the unions has increased in the last five years, these spaces represent less than 5% of app-based workers in India, says Apoorva, president of App-Based Karamchari Ekta Union (AKEM) which represents delivery workers in New Delhi.

‘We Can’t Keep Striking Again and Again’

The post-pandemic collective action has emerged in short, scattered bursts, a factor of how the platform economy is designed, to trap workers in a ‘digital cage’, activists say.

Bijender, 27, joined Swiggy Instamart during the 2020 lockdown, after his father was diagnosed with cancer. His enthusiasm ebbed as the company arbitrarily revised rate cards and earnings became unpredictable. When a revised rate card was quietly introduced last year, Bijendar rallied fellow delivery workers, from Swiggy, Zepto and BlinkIt, shutting down 10 stores in protest.

“It helped that I wasn’t alone, then they can’t block everyone’s IDs,” he says. The strike worked – briefly. After 15 days, the company quietly rolled back its promises. “What could we do? They know we can’t keep striking again and again,” Bijender says.

This is a dispersed sector, with a high turnover of workers who are everywhere but nowhere in particular, floating between apps, creating a churn too rapid for organising. “The traditional idea of going on strike goes out the window,” says Nihira Ram, who has organised with AIGWU earlier. “You need people to come out in numbers, but how do you get, say, Swiggy workers across the country to mobilise on a particular day?”

Unlike factory workers in 1990s Delhi, who gathered at mill gates, or Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers who meet at health centres, platform workers are dispersed digitally and geographically. Their “workplace” is the street, a client’s home or at the doors of restaurants. And they are rarely at the same place often enough.

This year, contract workers at Maruti Suzuki staged a successful protest in Manesar for fair pay and dignified working conditions because there was a site of work. “They could go again and again to the manager’s office, corner managers who had nowhere else to run. Workers were able to become an annoyance – and an important part of any labour movement is to become a pain in the ass,” says Nihira.

In 2021, women Urban Company workers staged a protest in front of the Gurugram and Bengaluru offices, after which the management agreed to improve working conditions. But since then, Nihira says, many physical offices have shut down and workers struggle to get a hold of the management.

Fighting Invisible Capital

While platform work continues in the tradition of informal labour like agriculture or construction – where legislations do not apply and where unions have struggled to find a foothold – it introduces a fresh challenge, says Aju John, a scholar of platform work and researcher at Humboldt University, Berlin.

“Informal workers fought against local factories and entities, but workers right now are fighting multinational billion dollar companies backed by hedge funds and venture capitalists,” he says.

Companies are also getting more smart about strategies to preempt collective action. Strikes would earlier happen when companies announced a new rate card price, points out researcher Ambika Tandon, citing the example of the Delhi-NCR wide strike by Swiggy workers. “Now rate cards are not announced but implemented in a phased way. Targets and incentives change weekly, and you don’t know how much you will earn next week.”

Workers are getting increasingly squeezed for time, says Bijendar. If 20 riders handled 100 orders, now 50 riders share the same area, each earning less. “We used to make Rs 300 in two hours. Now it takes four to do the same. The company has slowly taken away our spare time,” he says.

The lack of traditional job opportunities has created an almost inexhaustible source of labour that is educated and unemployed. Companies can no longer cope with the demand for gig work. A 2023 study found more than a third of food delivery workers are educated, and another, focusing on women data workers, showed 94% had a bachelor’s degree and 43% workers held STEM qualifications.

This labour pool is tempted by the promise of freedom in gig work and associated schemes like Zepto’s Rural Mobilisation Programme which guarantee earnings of Rs 35,000 a month. “I couldn’t find any work in Kanpur, so I came to Delhi for the RMP programme,” says Gopal*. He left less than a month later due to poor pay and living conditions and sheer exhaustion. Now he hopes to find an office 9-5 job.

Apoorva believes that the wages are so depressed that workers are doing double shifts and still not able to earn one single shift’s minimum wage. In Delhi, many AKEM workers are Bengali and Bihari immigrant migrants living in Jai Hind camp in South Delhi or JJ clusters in North Delhi, juggling multiple jobs as DTDC workers in the day and delivery riders at night.

This kind of work schedule leaves little time for participation in union activities.

Women are famously time poor, forever juggling unpaid domestic duties and care work. A majority of women in platform jobs are single mothers or the sole earners of the family, and also socially isolated.

“Women are always rushing – from client to client, then running back home to look after the children, then back to work. You try to speak to them and they say they will get late – either for the customer, or for the husband or mother in law at home,” Nisha says.

Subverting Resistance

Platform companies, say labour organisers, wield technological and structural tools that make sustained resistance nearly impossible. These include ID blocks, permanent terminations, transfers and false FIR threats, says Ambika Tandon, a gender and platform work researcher.

For 32 days between May and June, Mahima*, 42, pleaded with Urban Company to unblock her ID. The company alleged Mahima had “defamed” them by sharing a story about a customer who verbally harassed her, and suspected her of union activity. “I told them I want to work here until my retirement. But they didn’t listen to me,” she says.

In some places, resistance was met with violence. In New Delhi’s Prashant Vihar, a BlinkIt store manager reportedly turned off CCTV cameras before assaulting five protesting delivery workers in the presence of police personnel. In Malviya Nagar, Zepto workers striking over reduced payouts were detained and allegedly beaten by officers.

Mahima was allowed to return to the company on two conditions: she would not speak about the harassment, and she had to give up the names of people who she told. She shared the incident with her colleague and friend, later summoned for questioning by the company. “But who else can we talk to about bad customer behaviour except each other?” she says. Mahima’s relationship with her friend soured, but she says she had no choice – she had loans to pay and children to raise.

ID blocks and onboarding policies are profit-making tools, activists allege. Each new recruit pays up to Rs 1 lakh in onboarding and training fee, and it is in the interest of the company to keep blocking, firing, and hiring new people.

In 2023, when a group of women protested against Urban Company, their IDs were restored only after they signed undertakings promising to never protest again. In informal WhatsApp groups, workers were coaxed into adding management members to spot and dismantle union activity, allege activists.

These punitive actions against workers who join unions suggest an active resistance to worker collectivisation, says scholar Sai Amulya Komarraju.

Unlike traditional employment settings, platform companies have no grievance redressal systems, no arbitration, no transparency, or a notice before suspension. As we reported earlier, the labour codes refuse to register cases due in this sector because of the absence of any legal contract proving the employer-employee relationship. The proposed state-level protections in states would demand companies to follow a proper procedure in order to fire or penalise workers for participating in the strike. But legislations like Telangana’s are yet to be implemented, and experts worry they will be ineffective due to weak enforcement and lobbying.

Shaik Salauddin says unions are fighting both invisibility and fear of the algorithm: “We’re pushing for algorithmic transparency as a core demand.”

An analysis by RAWU of ride-hailing and delivery sectors showed workers don’t have access to data – and subsequently proof of unfair pay – about their past earnings or the rate cards, “which is required to understand wage changes and raise their voices against unfair pay and algorithmic volatility”. But, says Chandan Kumar, who organises with GIPSWU, workers are now beginning to understand data.

Labour used to be a tripartite issue discussed between governments, employer bodies, and worker representatives, but has been reduced to a bipartite issue especially after 2014, and worker representatives are sidelined in conversations, activists note.

The biggest challenge is psychological, Rikta says. The company depersonalises the union as an external entity. The right to withhold labour – once a core tool of protest – is being turned against the worker. “It is companies that force you to stop your labour; there are 20,000 other people ready to replace you,” she says.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.