The Women Who Brought Water Back To A Himalayan Village

In Salga, a Himalayan village once crippled by water scarcity, women revived dying springs with spades and science. Yet, they remain excluded from land ownership and decision-making, revealing deep gender gaps in environmental governance

- Varsha Singh

For years, Shobha Devi woke up at 4 am, in the quiet of dawn, to fetch a pail of water from her local spring. She had to hurry before the queues got longer as women and girls from her village and adjacent villages made a beeline for the slow trickling water. Tempers could flare easily in the biting cold as they jostled for one bucket of water.

Even at dawn, Shobha had to wait for three hours for her turn. And any delay meant a setback for her day’s schedule – cooking, farmwork, collecting fodder from the forest and so on.

This was once the daily reality for the women of Salga village in Kalsi block of Dehradun district in Uttarakhand. Natural Himalayan springs, which flow underground through the mighty hills and quietly emerge from cracks in the earth, once the life source of water in the mountainous pockets of the state, had begun to dry up, forcing women to walk farther and fight harder for water.

Erratic rainfall, seismic activity, and ecological degradation from land use change are impacting mountain aquifers. A NITI Aayog report says that half of the over 3 million perennial springs in the Indian Himalayan region have dried up or become seasonal, causing water shortages in thousands of villages.

Salga village, home to 33 families and around 600 people, received household tap connections under the Har Ghar Jal scheme of the Jal Jeevan Mission in 2021, with a government allocation of around Rs 29 lakh. However, the taps mostly remained dry due to the low supply from the nearby spring. The district administration appeared largely unaware of the problem.

Frustrated, Shobha Devi and other members of the Mahila Mangal Dal took matters into their own hands. In Uttarakhand’s villages, Mahila Mangal Dals — women’s collectives with 12 elected members and led by a president -– play a vital role in forest conservation, water management, and even serve as first responders during disasters. They also engage with social service, cultural preservation and community resilience. In this, they are supported by the state with financial aid and skill development.

Salga’s Women Water Warriors

“About a decade ago, the water shortage was so severe that women sometimes did not bathe for weeks,” recalls Nirma Negi, a resident of Salga. The elderly struggled with hygiene, and during peak summer, children cried due heat and sweat. “So the Mahila Mangal Dal called for a meeting and I was tasked with looking for possible solutions.”

Nirma had heard about the work of People’s Science Institute (PSI) on spring rejuvenation and how it helped increase the flow of water. In 2021, she persuaded a PSI team to visit the village and audit the water sources. But the men in the village were not convinced that the spring water could be recharged.

“Fetching water has always been a woman’s responsibility. We were the ones trudging up and down the rugged hillsides every day, carrying full buckets of water. Even pregnant women had no choice. Yet the men didn’t see our struggle”, says Shobha Devi. “So the Dal decided that we would do it ourselves.”

Salga has two springs. The main spring, called Chargad–-and connected to the village taps– is 2km away, up on the hills. The second spring, Devta ka Pani (water of the gods), is closer–500 meters from the village– and it is what the residents rely on for their daily use. “Villagers believe the spring is sacred and approach it barefoot as a sign of respect,” says Nirma.

When the water started to dwindle, no one knew why. They did not know the source of the springs. The PSI team helped the women understand the geology of the region. “We began by mapping the area’s hydrogeology, studying rock types, slopes, fractures, and water flow patterns, to identify where rainwater actually recharges the springs,” Anil Gautam, head of environmental programs at the PSI tells Behanbox.

He explained how the land use changes had disrupted this recharge zone. “People had begun farming there, the vegetation cover had declined, and a new road was built near Devta ka Pani, all of which reduced the spring’s flow. Climate change also played a role.

“Intense rainfall over short periods causes water to run off instead of being soaked into the ground and so the volume of water reaching the underground aquifers that feed springs was low, a pattern we observed across the Himalayan region,” says the PSI official.

Recharged Springs, Full Taps

The women of Salga, with the help of PSI, decided to treat the spring’s recharge zones on their own. The recharge area for Devta Ka Pani extended about 50 meters upslope from the spring and covered around 1 hectare of land, while the Chargad spring had a larger recharge zone of approximately 3 hectares.

“We picked up the fawda (spade), kudal (hoe), and daranti (sickle) and headed uphill to dig trenches in the recharge zone. Day after day, under the harsh sun, we cut into the hard mountain soil, paying no attention to the heat, exhaustion, and even our own health. There was just one thought in our minds — the water problem must end,” Shobha says. In the village meeting, the men refused to join in this effort.

They dug staggered contour trenches in the recharge areas to let water percolate into the ground. These were placed on moderately sloped hillsides to avoid destabilising the terrain. They planted fodder grasses and other vegetation around the trenches to hold rainwater and provide animal feed, and fenced the area to protect the structures.

Once the work began, men joined in. Together, about 25 women and 50 men carved nearly 650 trenches, each about two metres long, one metre wide and one metre deep, in just five days.

After the Chargad recharge area was treated, water began to flow through the household taps. Every home now has a storage tank at home. The village residents of Salga built a hauz (tank) near the Chargad spring, and laid pipelines to channel the water directly to their farms.

“We take care of the recharge area like it’s our own. We clear weeds, clean the trenches when they get filled with mud and even fix small animal burrows near the spring,” says Guddi Devi.

Nirma explains how they monitor the spring discharge. “In the monsoon, the water flows stronger. But in summer, if a bucket takes longer to fill, we check the trenches to see what’s wrong. Now we’ve learned that we also need to plant more vegetation around the recharge zone to hold the moisture.”

While the women shared their struggles and successes, two young girls arrived to fetch water in a small bucket. This continues to be a gendered role.

Land Rights, Lasting Change

The women of Salga are not just reviving a spring, they are setting in motion a ripple effect. The watershed not only regenerates groundwater but also replenishes streams, ponds, rivulets, and even rivers downstream. These benefits stretch far beyond the village, nourishing forests, wildlife, and entire ecosystems that depend on these water sources.

“Women in the Himalayas are often the primary caretakers of natural resources like water because their daily lives depend on them,” says Chicu Lokgariwar, an independent researcher in water conservation. Despite this, women still lack agency, especially land rights, which limits their ability to make lasting decisions.

Nirma, 35, is single and lives in a joint family of 28 members, including seven brothers. When one of her brothers passed away, his share of agricultural land was transferred to his wife, one of the few ways women are beginning to access land. Some families are now listing women’s names on land documents often to avail loans, subsidies, or while building new homes. Yet, as one of the leaders of the movement that recharged the springs and brought water back to the village, Nirma herself owns no land.

Despite the 2005 amendment to the Hindu Succession Act granting daughters equal inheritance rights, only 14% of all landowners are women, owning just 11% of the land. Most women gain land as widows rather than daughters, revealing how social norms often override legal reforms, argues this 2020 paper ‘Which women own land in India?’

In 2021, Uttarakhand became the first Indian state to grant co-ownership rights to women in their husband’s or father’s ancestral property through an amendment to the Uttarakhand (Uttar Pradesh Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act, 1950). The reform aimed to boost women’s economic participation and help them access loans by legally recognising them as co-sharers in ancestral land. Yet, the impact remains limited.

Madhu Chauhan, twice elected as president of the Dehradun Zila Panchayat and contesting again this year, believes land rights can help women strengthen themselves and their communities. “Wherever women’s self-help groups have got a chance, they’ve done good work. If women had land in their names, they could show even better results,” she says. “Some married women have started getting ownership, but daughters are still mostly left out.”

Families hesitate to give land rights to women, says Razia Beg, former chairperson of the Uttarakhand Bar Council and a Dehradun-based advocate. “If a daughter wants her share, she has to fight a long legal battle against her own family. Maybe we need an amendment to criminalise the denial of land rights to women. That might at least create some accountability,” she says.

Researcher Chicu believes that if women had both social recognition and legal power, especially land ownership, the whole approach to environmental governance could be more equitable and effective. “Expecting women to care more for nature because they are women places an unfair burden on them– one we never place on men,” she points out.

Forest Rights Out of Reach Too

While the women of Salga are actively conserving springs and protecting surrounding forests, most of them do not hold any formal rights over these natural resources. In Uttarakhand, where over 71% of the land is covered by forests, more than 70% of the population relies on forests for agriculture, fuel, fodder, and other daily needs. Many qualify for Community Forest Rights (CFR) under the Forest Rights Act (2006), which recognises the rights of Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers to manage and conserve forest resources they have traditionally depended on. Yet, as of May 2025, Uttarakhand has granted forest rights titles in only about only 3% of the total claims filed, placing the state among the lowest performers in forest rights implementation.

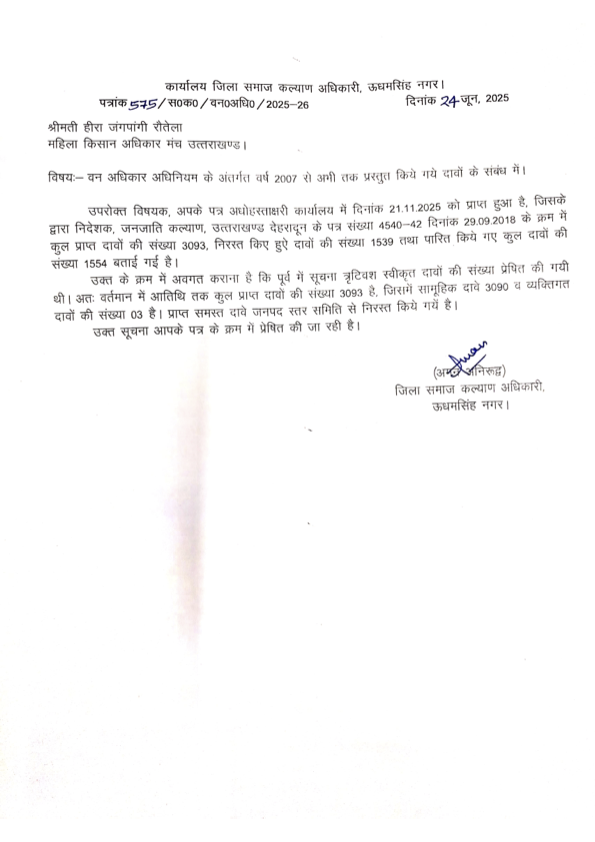

Even the ‘3%’ figure is inaccurate, an error admitted by the district administration itself: in response to an RTI filed on forest rights claims under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), the District Social Welfare Officer of Udham Singh Nagar clarified in June 2025 that all 3,093 claims received (3,090 community and threw individuals) had been rejected by the district-level committee. The officer acknowledged that the earlier data on accepted claims had been shared by mistake.

Sleepless No More

Legal recognition may lag behind, but in Salga, women are already reclaiming their space, trenching hillsides, reviving springs, and growing garlic and tomatoes.

“Now rainwater doesn’t just run off. We’ve saved it through trenches,” says Shobha Devi. “As it seeps into the ground, you can see the greenery return. Our forests, our fields stay moist. Earlier, we didn’t grow tomatoes or garlic because of the lack of water, but now we do, and they earn us good money. We also grow ginger, corn, pulses, rajma, wheat, rice, and millets.”

“Ab andhere mein nahi uthna padta, neend poori hoti hai, aur roz naha bhi lete hain (Now we don’t have to wake up in the dark, we get our sleep and bathe every day),” say the women amidst peals of laughter.

[This story is part of a new series “Climate Leaders: Women in Local Climate Action”, a collaboration between Womanity and Behanbox.]

All the stories in the series can be read here.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.