Number Of Working Women’s Hostels Declining, Funds Underused, Show Government Data

A deep dive into government hostel schemes reveals a drop in numbers, falling funds, and missed opportunities to support women migrants

- Anuj Behal, Suchak Patel

When Hiba and Teertha, both 21, left their engineering college in Kerala to coach in Delhi for the Graduate Aptitude Test in Engineering (GATE) exam, they knew there was an even bigger hurdle than the exam waiting for them —finding a place to stay.

“Our parents were very clear,” said Hiba. “They told us, ‘Until we find a place with full security, you’re not going.’” The two friends scoured online listings, mostly for paying guest (PG) accommodation, assuming that it somehow implied a certain kind of safety.

What they found instead were cramped, poorly ventilated rooms packed with three to six beds. “If we’re expected to pay that much, the least they could do is make them livable. It was impossible to imagine staying in those PGs,” Hiba recalled.

It was then that a senior from their college recommended a government-run working women’s hostel near their coaching centre. The place was clean, well-maintained, and livable — and most importantly, it convinced their parents of its safety.

“We’re well taken care of,” Hiba explained. “But we’re also living under a curfew. If we’re late, our guardians get a call—that’s their way of ensuring we’re ‘safe.’”

Despite the many rules, Teertha said the hostel offered good infrastructure. “We pay Rs 11,300 each for a double-sharing room. The room is spacious, there are open spaces around the hostel, even a library to study in. The food is clean—though it doesn’t quite suit our south Indian taste buds. Aside from the many restrictions, infrastructure-wise, it’s a good place to live.”

Working women normally have a far harder time than this when seeking housing. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of women migrating for work in India increased by 101%—more than double the growth rate for men(48.7%). Yet despite this surge, housing in Indian cities remains fundamentally exclusionary because it is primarily designed for families living in apartments, independent homes, or gated housing societies.

Urban planning documents and housing policies rarely account for single women who migrate alone for work, education, or other opportunities.

Improving access to safe and affordable housing for working women is increasingly being recognised as an economic imperative. A McKinsey Global Institute report, ‘The Power of Parity: Advancing Women’s Equality in India’, estimates that the country could add $700 billion to its GDP by 2025 by increasing women’s workforce participation, potentially accelerating annual GDP growth by 1.4 percentage points.

The same urgency is echoed in a NITI Aayog report, ‘S.A.F.E. Accommodation – Worker Housing for Manufacturing Growth’, which argues that women’s ability to work is closely tied to whether they can access secure and dignified housing. Drawing from global examples, the report highlights Vietnam’s initiative to construct 1 million social housing units for low- and middle-income families and factory workers—a move that helped push female labour force participation to nearly 70%.

In the absence of accessible private accommodation, women often find themselves navigating a deeply biased rental market where prejudices based on caste, religion, regional identity, and sexuality are common. The lack of a reliable support network further compounds the difficulties women face while relocating to unfamiliar cities or industrial clusters for the first time.

This demand-supply mismatch has serious consequences. Despite Indian women migrating more than ever before, only 27% are part of the labour force—the second-lowest among G20 countries, just above Saudi Arabia. One major barrier is the lack of secure and affordable housing in cities, where most employment opportunities are concentrated. Many times without a safe place to stay, women are unable to take up or sustain jobs, making dedicated hostels not just a housing solution but a necessary step toward increasing women’s workforce participation and achieving gender equality.

The finance minister, in her 2024–25 Budget speech, announced the setting up of working women hostels “in collaboration with industry” and creches. But data obtained through RTIs and parliamentary questions show that the number of working women’s hostels has been steadily declining, with no new facilities sanctioned in the last two years. Additionally underutilisation, and budget cuts reveal a system out of sync with the growing demands of women migrating for work.

Working Women Hostel Scheme of 1972

The Working Women Hostel Scheme was first introduced by the government in 1972 with the aim of providing safe and affordable accommodation to women who are living away from their families for work, training, or education. This has been renamed as the Sakhi Niwas which is part of Mission Shakti.

The scheme targets working women aged 18–45, including those who are single, widowed, separated, or married but living apart. It also supports trainees and students, especially from low- and middle-income groups, with an income ceiling ranging from ₹35,000–₹50,000 per month (state-dependent). Some hostels also allow children to stay with their mothers.

According to information received by BehanBox through an RTI response from the Ministry of Women and Child Development in May 2025, India has only 525 government-run Sakhi Niwas shelters, with a total capacity of 42,230 beds for working women—a critical shortfall considering the millions of migrant women across the country. Kerala has the highest number of hostels at 138, while states like Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh also have a relatively significant share. However, even in these states, the available capacity remains far too limited in comparison to the scale of female migration.

Take Delhi, for instance — the city has just 15 working women’s hostels with a total of only 2,427 beds. While the exact number of women who migrated to the city for work is unavailable, this figure appears inadequate when set against the 3.47 million migrant women recorded in the capital in the 2011 Census. The data also reveal that 10 states and Union Territories do not have a single operational working women’s hostel.

States like Bihar and West Bengal—home to a combined 220 million people, more than the populations of the UK, Germany, and France combined—do not have a single government-supported working women’s facility. Despite being chosen for development under the Smart Cities Mission in 2015, cities like Amritsar, Ludhiana, and Dehradun have no Sakhi Niwas shelters at all. This starkly underscores the neglect of gender considerations in India’s urban planning and governance.

The shortage of working women’s hostels was flagged as early as 2006 by the Parliamentary Committee on the Empowerment of Women, which noted that of the 873 hostels sanctioned since the scheme’s launch in 1972–73, only 607 had been completed, with completion reports for the remaining 266 still pending. The Committee noted that despite the rising number of working women, the availability of hostels had not kept pace. It described the government’s performance as “very dismal.”

But rather than expanding the network of hostels, the number of functional Sakhi Niwas facilities has seen a steady decline. In 2006, there were 607 hostels in operation. According to data shared in response to a parliamentary question, the number of operational Sakhi Niwas hostels dropped from 500 in March 2022 to 494 by December 2023, and further declined to just 463 by December 2024.

On July 24, 2024, the government informed the Rajya Sabha that no new hostels had been sanctioned in the past two financial years — 2022–23 and 2023–24. However, this figure appears to conflict with data obtained through May 2025 RTI response, which cited 525 operational hostels. This suggests either a sudden increase between December 2024 and May 2025, or a potential discrepancy in official reporting.

While a few new hostels were announced or inaugurated during this period, they remain limited in scale. One Sakhi Niwas hostel was inaugurated in Roop Nagar, Jammu. The Haryana government announced plans to construct hostels in Faridabad and Gurugram. Maharashtra’s Women and Child Development Department sanctioned ₹42 lakh for setting up 11 leased hostels in cities like Mumbai, Pune, and Thane. In Uttar Pradesh, the government announced the launch of 18 new Sakhi Niwas hostels across nine cities, including Lucknow, Noida, Varanasi, and Gorakhpur, by the end of October 2024.

As per a Press Information Bureau release, the Centre allocated ₹5,000 crore under the Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment for the construction of women’s hostels, and released the first installment to 28 states during the 2024–25 financial year. However, the completion status of these proposed facilities remains unclear.

Even the limited number of existing hostels are not running at full capacity. An April 2025 RTI response filed by BehanBox revealed a drop in occupancy in working women’s hostels in Gujarat—from 1,165 in 2015-2016 to just 869 in 2024-2025. A separate RTI response from the same month showed a similar decline in Delhi, where occupancy fell from 1,777 to 1,547. [Notably, the April response from the Delhi government listed only 14 functional hostels, contradicting the Ministry of Women and Child Development’s May 2025 reply, which put the number at 15].

As per the ministry’s May data also stated that out of a total capacity of 42,230 beds across hostels in India, only 37,664 were occupied.

Mukta Naik, a rental housing expert explains that low occupancy is partly due to the narrow demographic the scheme tries to serve. “Most of these hostels are designed for single women. But in India, migration for women often happens after marriage, and they usually move with their families. That means the hostels are only targeting a small slice—single women in the brief period between education and marriage,” she says.

Naik also points out a number of structural problems. “The hostels were built where the government already owned land, not necessarily where jobs are concentrated. That affects access. On top of that, surveillance within hostels is intense, making many young women uncomfortable. There’s also a lack of awareness—these facilities are poorly advertised, so many don’t even know they exist.”

Meanwhile, the housing market has evolved. “Private and Informal rental options like PGs and shared flats have grown rapidly, especially around work and education hubs. These options are often more flexible and better located, so in a way, the private sector has responded to the demand more nimbly than the state,” Naik says.

BehanBox has written to the Ministry of Women and Child Development seeking clarification on the gap between capacity and actual occupancy and will update the report upon receiving a response.

Low Allocations, Lower Utilisation

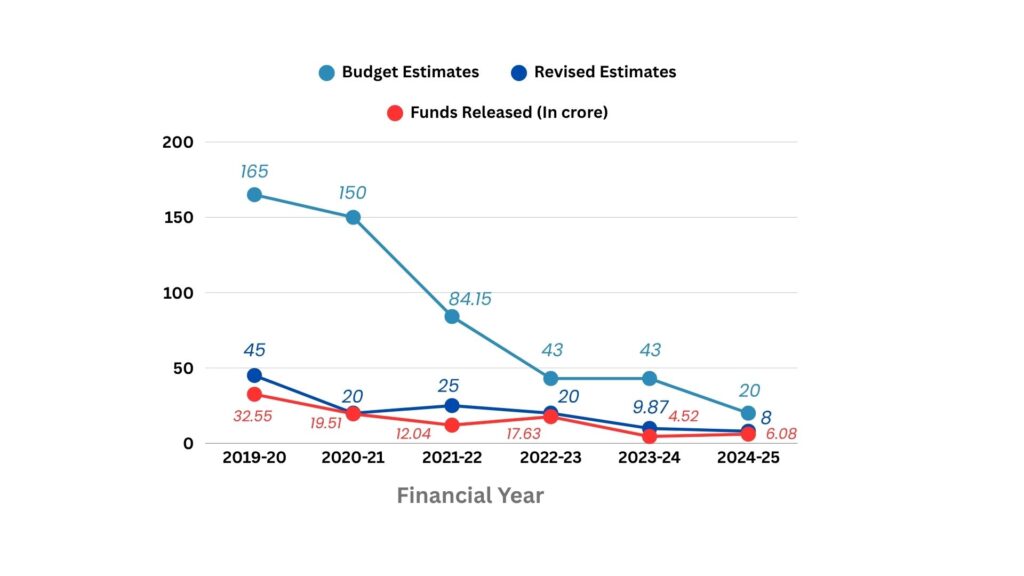

Budgetary support for women’s hostel infrastructure has steadily declined over the years. Government data reveals a sharp year-on-year reduction in allocations under the previous scheme—from Rs 32.55 crore in 2019–20 to just ₹4.52 crore in 2023–24. Earlier, grants-in-aid were extended to states and Union Territories for constructing new hostels, expanding existing ones, or covering rental costs.

However, with the launch of the Mission Shakti programme on April 1, 2022, the erstwhile Working Women Hostel (WWH) Scheme was restructured and renamed the Sakhi Niwas Scheme. Under the new framework, financial assistance is restricted to hostels operating out of rented premises, covering rent, management, and repair costs. Crucially, the scheme no longer supports the construction of new or transit hostels.

In contrast to the declining budgetary trend, the Centre’s recent announcement of a substantial Rs 5,000 crore allocation under the Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment, that falls under the Working Women Hostel Scheme, offers some hope. So far, 28 states have submitted proposals to the Department of Expenditure (DoE) based on their assessed needs. However, the real test lies in execution. Past spending patterns raise concern: over the last six years, while ₹505 crore was allocated for women’s hostels, only ₹92.33 crore—just 18%—was actually spent, underscoring serious gaps in implementation.

The Parliamentary Committee report tabled in March 2025 flagged persistent issues in both funding and execution of the Sakhi Niwas scheme. It noted that while ₹43 crore was allocated in the 2023–24 Budget Estimates (BE), the amount was drastically reduced to ₹9.87 crore at the Revised Estimates (RE) stage. Actual spending was just ₹4.52 crore—only 10.51% of the BE and 45.79% of the RE. The Committee underscored that this pattern of chronic underutilisation has remained consistent over the past five years.

Surveillance, No Childcare, Outdated Eligibility

“You can’t leave before 6 in the morning, and not after 7 in the evening. If you want to order food, it has to be before 10. And anyone visiting you must be approved by your guardian,” says Teertha of hostel conditions. “Why should this be the case? We’re adult women. But we’re okay with it too, because it’s the very presence of surveillance that convinced our parents to place us here in Delhi.”

Another major gap we observed firsthand in working women’s hostels in Delhi and Ahmedabad was the lack of daycare facilities—something the scheme itself mandates. The RTI response from the Gujarat Commissionerate of Women and Child shows that out of 15 working women’s hostels in the state, only two have daycare centres, even though 14 are equipped with CCTV cameras. This pattern holds nationally. A report by the National Commission for Women found that out of 254 working women’s hostels studied across the country, only 72 had daycare centres.

Additionally, Naik argues that the scheme must not only expand but also reorient its focus toward working-class women, who are in greater need of housing support. But that would require rethinking how the scheme operates.

“We know that working-class women are largely concentrated in the informal sector, where they often lack formal proof of employment, valid identification, or the ability to make security deposits,” she says. “So if the government truly wants to shift its focus, it must first pay attention to demand aggregation, working with NGOs and employers who are already doing this, and invest in new housing typologies and operational models that meet the needs of low- and middle-income working women across the life cycle. These could be hostels/dormitories for single women. Providing vouchers that can subsidise market rentals for married women with families could also be a pathway forward.”

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.