Lessons From Kudumbashree’s Gender Crime Mapping Survey

In Kerala, the grassroots women’s programme for empowerment and livelihood, Kudumbashree, is mapping gender-based violence at the panchayat level. Despite its methodological limitations, it can help design panchayat level interventions

A unique ‘conclave’ took place in February this year across all the 14 districts of Kerala. In these meetings, Kudumbashree members took to the stage to release the findings of their annual ‘gender crime-mapping survey’. Frustrated by the lukewarm response to their annual reports to the panchayat or local government representatives over the last three years, they chose to release these findings publicly for the first time to bring greater attention to the gender based violence (GBV) pandemic in the state.

In its third edition, Kudumbashree’s annual ‘gender crime-mapping survey’ is the first of its kind localised survey mapping gender based violence in India. It was launched in 2022 by members of this grassroots programme for women’s empowerment and poverty eradication after cases of domestic violence started spiking during the Covid lockdown.

The survey departs from the national statistics on crimes against women released annually by the National Crime Records Bureau. Categorised based on different laws and sections, the data for the national statistics is a collation of reported offences by women at the local police stations. However, such data is almost always underreported due to social and institutional factors as several studies have noted.

In contrast, the Kerala model captures women’s experiences with 42 types of violence from across six categories of perpetrators at the panchayat level. It also maps the localities within each panchayat that are prone to gender-based violence and suggests measures to reduce it.

In Kerala, a state with some encouraging gender indicators, NCRB data suggest that reported crimes against women rose from 10,139 to 15,213 between 2020 and 2022. The conviction rate was 10.3%. The Kudumbashree survey has some methodological limitations as we explain later, but it bridges an important information gap and widens the scope and understanding of the specific nature of gender based violence. But there is a chasm between how the Kudumbashree initiative and panchayat representatives see this violence. This, say Kudumbashree members, is a common problem across the state’s panchayats.

How the Crime Mapping Is Done

The first gender based crime mapping was piloted by Kudumbashree in 2012-13. The findings paved the way for panchayat-level Gender Resource Centres (GRCs) and district-level help desks, named Snehita, to support survivors of gender based violence. Since 2022, these surveys have become an annual exercise.

Kudumbashree selects a fresh set of panchayats,six per district, each year for the exercise,so that all the state’s 941 panchayats can be covered over the next few years. The state government spends around Rs 1.5 crore on the project annually.

Around 50-100 respondents are picked in every ward, totalling to about 1000 or more women in a panchayat. The collective’s resource persons identify these respondents mainly from Kudumbashree’s ayalkkoottam (neighbourhood group) that comprises entirely of its members. Most women are between the ages of 41-60, as they have been part of Kudumbashree since its launch in 1998. Some respondents are also from Kudumbashree’s auxiliary groups, composed of younger women between the ages of 18 and 40.

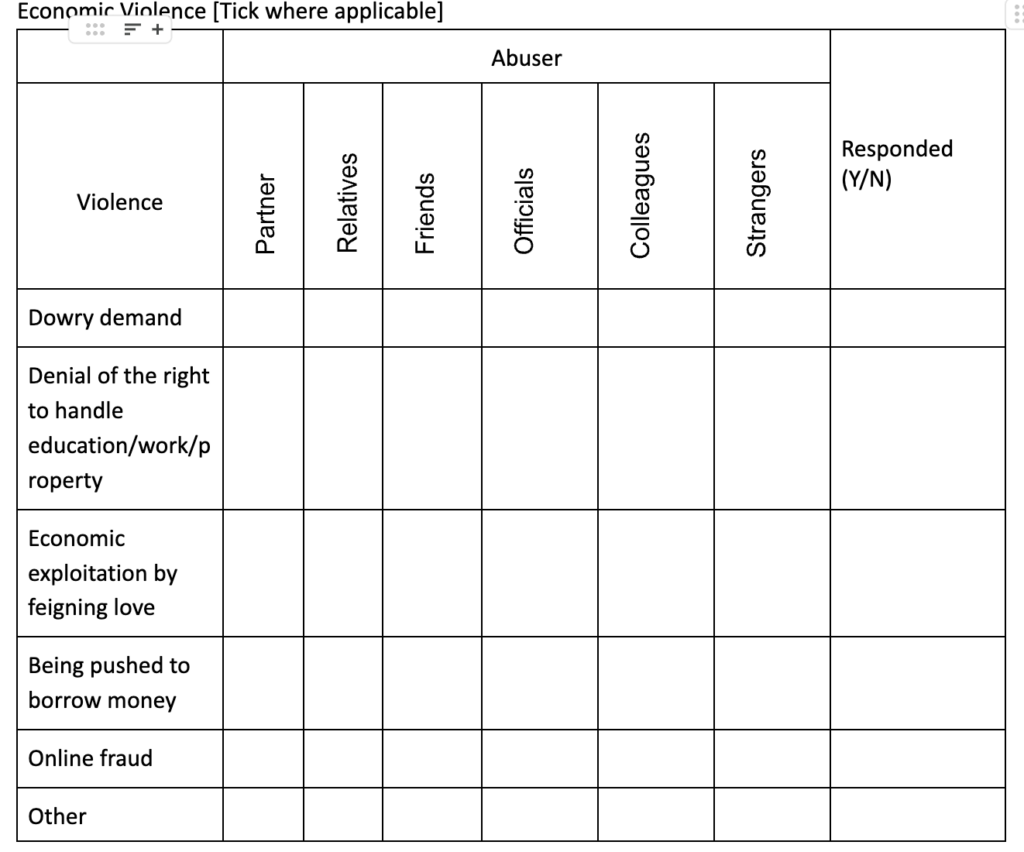

The survey collects data under six broad categories of gender based violence — economic, physical, mental, sexual, verbal and social. Each category has four to nine sub-categories. Economic violence, for instance, includes demand for dowry, denial of the right to handle education/work/property, economic exploitation by feigning love, being bullied into borrowing money, and online fraud.

The survey also collects responses on the perpetrator of the crime, classified as partner, relative, friend, official, colleague and stranger. This is a rare departure from the NCRB statistics.

The National Family Health Survey which is a representative survey also collects data on gender based violence but restricts it to physical and sexual violence. Under the sexual violence category, the NFHS identifies and collects data for 15 types of perpetrators including former/current husband and boyfriend, teacher, soldier, priest/ religious leader among others.

The woman respondent can also indicate if she responded to the violence. ‘Response’ here means any activity– filing a police complaint, discussions with family members, etc.

The results indicate both the scale of violence as well as the kinds of perpetrators. In Aruvappulam panchayat in Pathanamthitta, for instance, of the 749 respondents, 11% reported facing dowry demands from their partners, whereas three times as many (37%) reported facing it from the partners’ relatives. In ‘Denial of the right to handle education/work/property’, relatives were the main perpetrators (22%) followed by partners (13%).

The survey includes a separate questionnaire where women can select the reasons why they did not respond to violence. This is also meant to make women consider responding in the future, says B Sreejith, Programme Officer (Gender) at Kudumbashree.

Other than the survey, resource persons also conduct ‘spot-mapping’ in each ward – pinning locations where verbal, physical or sexual violence are known to have occured. This information largely comes from their public meetings with panchayat ward members, ASHA workers and others. These could be locations where an instance of rape case was recorded, or public places where men are known to harass women and so on.

The surveys provide disaggregated, local data which is directly submitted to the respective panchayats. The data is not consolidated at the district or state level currently.

But collecting this data is not an easy task.

“On the day of the survey, we hold a session in the morning familiarising respondents with the different categories of violence and perpetrators. We get them to fill the form the same afternoon so that they don’t feel inhibited about sharing information later,” Sreeja Mahesh, Kudumbashree community counsellor in Pathanamthitta and a veteran of the survey told Behanbox. The women are asked to record their experiences so far, especially in the previous 5-7 years. They are also informed of the support systems available to them.

But resource persons across districts say that convincing women to disclose information is a challenge. Many respondents do not see the point of reporting violence after having suffered it for years. Some also worry of consequences, or believe that certain acts mentioned in the form do not qualify as violence.

“Some respondents leave out entire sections in the form as ‘Not applicable’. We can’t force them to respond, we only try to convince them that sharing data will help future generations even if it can’t change their past,” says Bibitha K, help desk staff of Snehitha in Kannur district. Of the 2000 women surveyed in her panchayat Pappinisseri this year, 8% refused to fill forms altogether.

What Surveys Reveal

Across panchayats, data reveal some common patterns. For starters, women faced most violence within their own homes, a pattern that aligns with the findings of the NFHS. At home, the most common form of violence reported was verbal violence, especially abusive speech, threats, and insults about the women’s natal family. Kudumbashree’s discussions with survey respondents also shows that men’s alcoholism is a big factor in gender-based violence in both public and private spaces.

Besides, the results show that a large number of women were marking ‘No’ in the ‘response’ section of the questionnaire. This could mean any action – from resisting violence themselves, reporting it or seeking help for it.

In the case of sexual violence, women seemed more likely to take action if the perpetrator was a stranger rather than their a partner. For example, women in several panchayats reported exhibitionism and non-consensual touch – usually by strangers – as the most common types of sexual violence. Fewer proportion of women took any action against their own partners for acts such as non-consensual sex and insistence on unprotected sex.

In Aruvappulam panchayat, in 83% of cases of exhibitionism, strangers were reported as perpetrators and half the survivors responded to this. Strangers were also the perpetrators in three-fourth of cases of frotteurism (rubbing genitals against the woman’s body without her consent), and 85% of survivors responded. In this panchayat, women’s partners were the main perpetrators (93%) in the sub-category ‘insisting on sex when the woman isn’t interested’. But only a quarter of survivors reported responding against it. Partners made up 97% of the perpetrators under the category ‘insisting on unprotected sex’ as well, and only 31% of survivors reported responding against it.

This pattern of underreporting of domestic violence in Kerala aligns with the findings of a World Bank working paper of 2017 which showed that the underreporting of domestic violence is 9 percentage points while close to negligible for physical harassment in buses.

Underreporting of domestic violence is not unique to Kerala. A 2020 study published in the British Medical Journal had found that every third married woman in India face spousal violence but only one in 10 seek any help and just 1% report it to the police or healthcare personnel. Normalisation of spousal violence was a major reason for low reporting. In the Kudumbashree surveys too, women across several panchayats reported fear, concerns about family honour and lack of awareness about legal remedies as the main reasons for not responding to violence.

“Women know that physical assault is violence but don’t think other acts, such as their husband or in-laws talking down to them, is violence too,” says Sreeja of Kudumbashree. She says that one of the aims of conducting the survey is to make women aware of the many forms of gender based violence.

Bibitha who oversaw the survey in Pappinisseri panchayat, Kannur, says, “After the survey, six women filed complaints with us, of which two were domestic violence cases. One of the women wanted a divorce, so we helped her file the case and access legal aid.” The organisation also intervened on behalf of senior women who disclosed issues they faced at home.

The survey has dealt with hurdles from its very first moment, Sreeja told Behanbox. When the pilot survey was announced in 2012, many members of the public, especially men, were upset and afraid. “The husband of a Kudumbashree member who was physically abusive didn’t even allow her into their house after she filled out the survey form. She was able to enter the house only after Kudumbashree intervened,” recalls Sreeja. While women are now more aware of what gender violence is, they are still worried about speaking up despite the complete anonymity of the survey design, she adds.

Poor Panchayat Response

The larger goal of the survey is to bring systemic changes at the panchayat level. The reports often recommend awareness sessions for men, police patrolling in mapped areas, working street lights, and citizens’ groups that can be visible at public sites like bus stands.

But most panchayats have only responded with infrastructure fixes such as repairing street lights, prompting Kudumbashree to organise conclaves with panchayat representatives this year. Some panchayat responses were disheartening, says Pathanamthitta counsellor Sreeja of the conclave in her district: “The panchayat representatives spoke without any understanding of gender violence, and even seemed to hint that women are to blame.”

PK Shyma, president of Koodali panchayat in Kannur surveyed by Kudumbashree in 2023-24, says they organised two awareness programmes for men and ensured police patrolling at a football ground. “A limitation is that there are no provisions to spend panchayat funds for gender-based programmes for the general public. So we have to find sponsors for these programmes,” she says. They could use the allocations for Kudumbashree which they have in some cases, she adds. But Kudumbashree resource persons say their own awareness programmes are attended only by women and that reaching out to men is difficult without panchayats’ support.

L Shylaja, gender activist and resource person at the Kerala Institute of Local Administration (KILA) that trains panchayats, says it’s possible for panchayats to set up awareness classes for the general public as a new project using its general funds.

Sreejith says Kudumbashree will continue to hold the annual conclaves, and is exploring options to get panchayats to implement the survey recommendations better.

Evolving Methodology

The annual surveys fill an important gap but methodological issues remain, despite tweaks. One central issue is that the data cannot be easily consolidated. For example, a respondent can mark multiple types of perpetrators under a sub-category of violence. But when consolidating survivor numbers under that sub-category, the survey report takes only a total count of the responses (and does not count the number of unique respondents), which inflates survivor numbers.

C Satheesh Kumar, director at the School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences at Kerala University, says a core issue is that the survey has not followed the protocols of random sampling. Analysing the report from Aruvappulam panchayat, he says: “The total sample size from the panchayat, while being sufficient, doesn’t follow a scientific sampling technique. For example, the sample size from each ward should be proportional to the population of that ward, else the results can be misleading.” There is double counting during consolidation in some places, and some sub-categories of violence as well as perpetrators seem to overlap, which can confuse respondents, he adds.

However, Satheesh Kumar reckons the reports are useful even in their current form to help panchayats design targeted interventions as suggested by Kudumbashree. He suggests that involving experts like statisticians, gender researchers and psychologists along with Kudumbashree members to design the survey questionnaire and methodology can make the survey design, analysis and sampling more robust.

Some of these changes are already in the works including a writeshop involving social science researchers, college professors to finetune the methodology before the next round of survey in June, says Sreejith.

With a proper, standardised methodology and format, the survey can inform policy making at the state level too, says economist and gender expert Praveena Kodoth. “If data from all panchayats is available over a 10-year period, it can be aggregated and compared. Then you can look at it in terms of various other characteristics — for example, how violence varies in urban and rural areas or by the woman’s age or marital status, whether women-governed panchayats have better outcomes and how violence is linked with facilities available in panchayats, etc.”

Kudumbashree, which is recognised as Kerala’s State Rural Livelihoods Mission, has presented the survey model at the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM), the poverty alleviation programme of the union ministry of rural development. But replicating the survey in other states could be challenging, says Praveena. Kudumbashree’s network has deep reach even in remote tribal areas. In other states, it would fall upon the panchayats to conduct this. Costs are another challenge. “Kudumbashree’s work is largely voluntary. So other states would have to largely foot the costs of the survey or mobilise voluntary workers,” says Praveena.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.