‘Reading For Pleasure Pauses The March Towards Women’s Productivity’

In BehanBox Talkies, we explore ideas through the lens of scholars. In this installment, we interview researcher and writer Aakriti Mandhwani on women’s identity as readers, past and present

In our editorial series BehanBox Talkies, we explore ideas through the lens of scholars.

In her book, Everyday Reading: Hindi Middlebrow and the North Indian Middle Classics, literary scholar Aakriti Mandhwani traced the reading culture among women and north Indian middle-class families in post-independent India. Her study included popular Hindi middlebrow magazines like Sarita and genre magazines like Rasili Kahaniya and Maya – aimed at Savarna Hindu families – to show how women’s identity as readers was constructed through a mix of gender norms, nationalistic currents and the economics of publishing.

The book also looked at how women from different socio-economic and religious backgrounds moved through their universes. Later, Aakriti also started a digital archive, ‘South Asian Women Reading’, a compilation of images of women reading that she discovered in her research and a crowdsourced initiative which invites print historians to submit their findings.

In this wide ranging conversation, Aakriti talks about the reading and production culture of post-Independence India, women as readers of romance, as creators of literature, and what it means to read for oneself and for pleasure.

What did you grow up reading, and what literature did the women in your family have access to?

I grew up in a pretty multilingual household – so I heard a lot of Sindhi, Hindi, Punjabi and then there was English. Subscribing to magazines was still seen as aspirational (most family members didn’t read them), so apart from the Sindhi and English language newspapers that my grandfather enjoyed, we got Outlook, India Today and the much fancier and more expensive Newsweek that my father wanted to read. I myself grew up reading Tinkle, Chacha Choudhary and, much later, the Archie comics – we bought these during train journeys. I was a very voracious reader – so the Famous Fives of my childhood gave way to the Bronte sisters by the time I was in the ninth grade (all thanks to my English school teacher Shalini Dutta). But still there was no Indian novel in sight – and my life changed when I read Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy issued from the school library. Of course, it had to be read in secret under the blankets.

Three wonderful women who I dedicate the book to had three very different access to reading. While my maternal grandmother read a variety of Hindi popular and high literary fiction, my paternal grandmother, dadi, couldn’t read at all. She decided to learn very late in her life. At that point in time, we didn’t think much of the mother reading. The mother’s reading was not privileged at all — so much so that I don’t have any memory of her reading avidly, talking about what she read, or taking time out to read. I would see her encountering magazines at a beauty salon or at the dentist. My mother’s reading – of magazines like Sarita and Women’s Era – was entirely eclipsed by my father’s assertive (and loud) construction of himself as the avid reader of far more “literary” things – he was the first English graduate from this Sindhi household and he made sure everyone knew it.

I understood much later that he was no different from my mother in his consumption practices–he was an avid consumer of middlebrow objects. For example, he would endlessly wax [lyrical] about Shakespeare, but Shakespeare is the most middlebrow of authors at this moment in time from the point of view of a ‘middle class family’ – he’s aspirational, endlessly accessible, everybody wants to lay claim to him.

Were you interested in women’s experiences with reading and access to books?

I honestly went into the project trying to decode the history of pulp. I was sure that I was going to find strong women readers of it. But the research unfolded even more confident and assertive readers than I could have dreamed of.

Historically so much of women’s reading has been rooted in surreptitious and collective reading practices, or just in the language of ‘service’ or ‘duty’. What I found remarkable was the sheer volume of exchanges [through reader letters] taking place in these magazines – among readers, writers, editors, so many of them women. They really did not hold back on their opinions. These women not only liked or disliked stories, they argued factual discrepancies in them, they told off other readers and writers if they didn’t agree with their opinions, they didn’t even spare the editor. This may very well have been a choice on the editor’s part, to display this kind of a strong, assertive female reader (unfortunately we don’t have any other correspondences that survive). However, this editorial choice gestured to more readers that such opinions would be welcome.

Also in the 1950s historically, the fact that these women thought of themselves as readers was a mark of pride. And they didn’t think of themselves as readers who would only comment on one thing. They’re saying we deal in the particulars: they are interested in being readers of [articles on] household chores, of literary short stories, and of gossip columns. For context, second generation feminists are also writing at this time elsewhere in the world, and they are thinking about this ‘masculine sort of universalism’ and whether they need to prescribe to it, but that thinking is not happening with these women.

What picture do you draw of women readers and creators? Would you say their caste, economic, or religious identities shaped their reading choices?

I do want to stress that as generously as these magazines included, they excluded. That means that these women very much came from mostly Savarna Hindu backgrounds. They read widely, across genres, across fiction and non-fiction, however, I found next to no minority representation in these magazines. There was a smattering of material relating to knowing about the “tribes” of India, however, the gaze is very much that of an imperialist/pseudo-benevolent outsider looking in.

While it is true women are reading in exciting ways, these are middle-class women who operate in the context of their time. We have to bring the conversation back to caste and the exclusionary practices of these very women.

Journals of the time framed women as being in service to the nation or the family. Did they inform women’s domestic lives or reproduce gender norms?

Absolutely. Sarita and Dharmyug crafted confident women readers and writers, but they remained mostly preoccupied with marriage, love, family. But these were also undercut by what can only be termed confrontational arguments with these very systems. How can we, for example, make sense of a woman writer who told women to not wear the sindoor because it looked “ugly”, “like a signpost”? Or another article that advised women to never bow their heads, even in supplication to elders, because it would mess with their posture? I find these negotiations with gender norms very interesting in these magazines.

Women’s magazines and paperbacks are often seen as frivolous in comparison to non-fiction books or political magazines. Did this bias impact women’s reading habits?

The magazines I discuss in the book weren’t called “women’s magazines” at all – these were marketed as family and general interest magazines. Often advertisements for these magazines literally show the family in battle with each other about who gets to read first. However, since women read them in numbers, many “literary” magazines looked down upon them. In fact, a famous writer moaned that Dharamvir Bharti, Dharmyug’s editor, had sacrificed himself to run a vyavasayik (commercial) magazine. The critique may be of commercialism, but inherently coded was also the message that just because the family (women included) read them, they were not literary enough. Even now, this bias exists – for example, “feminine” genres still need to jostle for space to be taken seriously. Many times, it is these very genres that drive sales but are still looked down on.

We have such little scholarship on contemporary reading practices; so much of our time is spent lamenting that people are not reading, that actually the work of figuring out what they’re reading is not being undertaken at an industrial scale. This data is available with big companies who will not share that data with research scholars. Research lags into women’s reading habits due to a lack of data, or maybe it’s a lack of interest.

But what we know for sure is that women are reading. Anecdotally, I can say that women are reading notes, and women are reading in ways that perhaps don’t constitute reading sometimes: for instance, reading on phones these episodic novels, fan fiction, or romance stories.

We see a surge in the popularity of romance novels, such as those by Colleen Hoover. How is this genre shaping the identity of women as readers?

We have to reckon with this difficult problem of women as readers of romance. How can you call yourself a “feminist”, or how can you think of yourself as somebody who’s not interested in romance or fashion but still reads literature that are “cowboy romances” or “mafia romances”, where men actively glorify in masculine roles? A lot of young feminists voice a discomfort in wanting to engage with this material.

We can also see why readers of romance are reading Colleen Hoover. Her last book that was made into a popular movie was actually about domestic violence, so we have to take cognisance of the kinds of imaginative universes women are able to evoke in these fictional worlds that they often quote as fantasy. They don’t want to have these abusive relationships in real life, and a certain desire is met through the reading of these romances. And maybe this is an expression of desire classified as queer. A podcast made this argument that the rise in stalker romances is a response to our worlds becoming much more conservative.

On the other hand, women are also making and consuming the Boys’ Love shojo manga (a genre aimed at a young female audience) which basically rehashes the trope of two men falling in love. Why are so many women interested in consuming stories of men falling in love with each other? Maybe they’re trying to break the gaze. Women’s creation of literature is a way to counter that conservative strain, but also give into it — it’s confusing.

There is the idea that only men produce important ideas while women produce gossip. What about women creators at the time – what were their motivations?

Women have always had different motivations, right? For example, there’s an upcoming essay by Melina Gravier on Khatoon e Mashriq, an Urdu magazine edited by a woman set in the same time period. The women are asking very open questions about divorce, what women are entitled to, and what it means to be a citizen of this country. The Muslim women were trying to find a solidarity or community similar to what is geographically constructed in India. We can only imagine what kind of solidarities are built and what they wanted to build.

In another work, Priyasha Mukhopadhyay talks about the Indian Ladies Magazine which was being published in Chennai where women read book reviews of books published in America, Canada, and beyond – books that they will never read. Women were trying to build very feminist solidarities around the world from the act of reading.

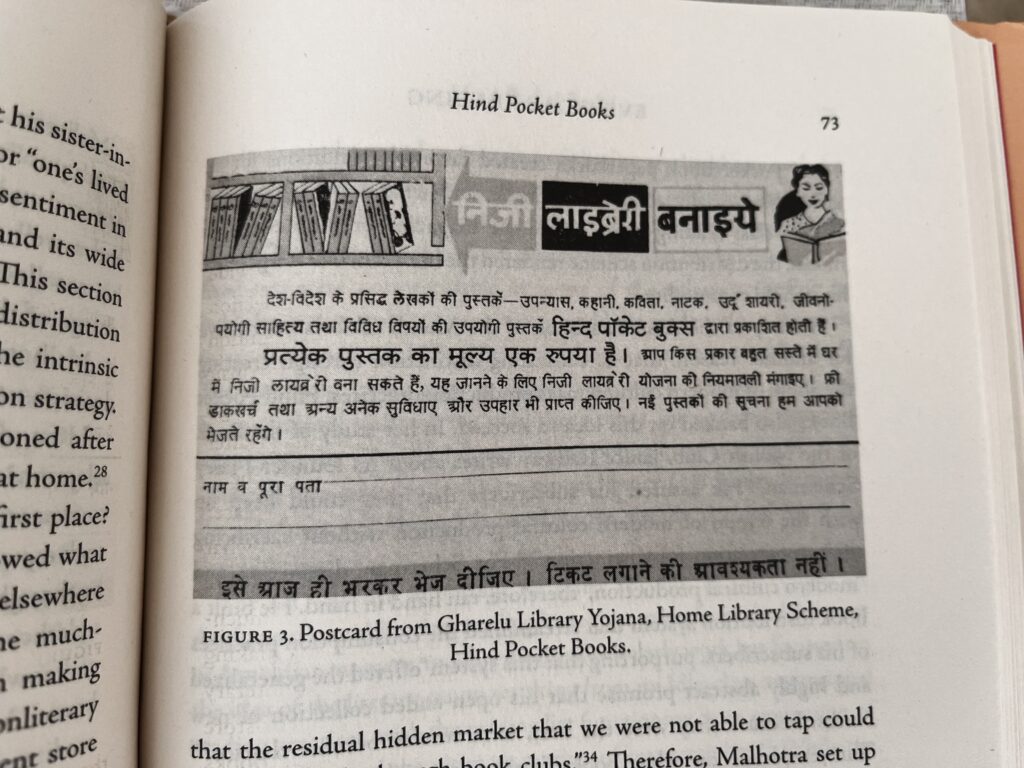

Did you come across Indian women writers or publications led by women lost to history? Also, what can be done to make it easier for women to create and access literature today? The Hind Pocket Books library scheme, for instance, introduced the first-ever mail order book club for readers.

So many women writers and publications have been lost entirely. And these were writers who were at the height of their fame when they were writing for these magazines. I’m absolutely mystified by the fate of Vimla Luthra, for instance, who was so widely read. Some writers like Shivani thankfully are still kept alive in public memory.

One of the biggest barriers to entry with reading is access – despite being subsidised to a great extent, books are still expensive. Another problem of access is representation – traditional print publishers have still not produced enough diversity along lines of caste, queerness, minority representation. All around the world women have taken matters into their own hands – so much reading today across happens in fanfiction or self-publishing, for example.

Some infrastructure in India sort of resonates with these schemes of the past – for example, Pratilipi is doing exceedingly well, with so many of its writers and readers coming from across languages and readers being able to read thousands of books for a monthly subscription. But public and travelling libraries used to be the pride and joy [of communities] and they created access. Well-stocked and approachable community libraries are the need of the hour.

You said in an interview that “non-surreptitious” reading for a woman, to read for pleasure is almost radical. What did this reading for pleasure look like?

We can only imagine. The letters to editors construct their women readers as absolutely confident, excited, placing reading at the center of their existence. The letters don’t tell us how these women were snatching time to read. It means something for women to construct themselves this way, or it means something for the editor to choose to construct women in this way. What these magazines don’t tell are stories of women like Rashsundari Devi or her autobiography, Amar Jiban – about how a woman snatched time to teach herself to read in the kitchen using rudimentary tools, and then ended up writing her own autobiography.

What does this ‘right to read’ look like today, when the economy promotes hustling and slowness is discouraged?

It looks like many things, and we only need to look around us to see how women even manage to read. All around us mothers snatch time to evoke this right while their children allow them rest, grandmothers find themselves guilty of doing any reading that isn’t sanctioned by their husbands or gods (so much research has shown how sanctioned religious genres were what women were first encouraged to read). No one even bothered with educating my own grandmother who couldn’t read till she was 60.

In the digital space, there’s an over-dramatisation or romanticisation of ‘reading’. A bookstore I visited last year said we are inundated with people who are just here to take photos with our books, but they’re not buying the books. At the same time, these Bookstagrams, BookToks, book clubs build communities that end up being a safe entry point to reading, making just sitting with a book to be a romantic thing to do. If that makes somebody join a book club, actually read the book, or even construct themselves as a reader, that by itself could be framed as a rebellion. Outside of elite Delhi circles, Lodhi Reads-adjacent initiatives have popped up in tier 2 and tier 3 cities, like Alwar Reads, and this Insta reel-to-real life conversation is perhaps a radical and generative thing, that you’re stopping and taking the time to read. I’m not even trying to make a romantic argument here. Reading for pleasure is pausing this (very ridiculous) march towards women’s productivity. Reading for pleasure interrupts phallogocentric egocentric time. I really enjoy students telling me they read fanfiction, I love it when I see a woman on the metro on the pratilipi app.

What was it like to be a woman researching women’s literature, and working with the archives at Delhi Press, Marwari Library, and Hindi Sahitya Sammellan?

Interestingly, while most of the libraries I worked at are places where an institutionalised (and violent) idea of Hindi first took root, these archives are still relatively easily available to access – you need an official sounding letter, and loads of time (half the time they are shut because of some event). A benevolent paternalism of course abounds each time I tell people at large that I am working on “women and family” magazines – of course these aren’t “political” materials, I couldn’t possibly be harmful.

This is something that I noticed throughout not only with my time in the archives but also moving through academic spaces. Stree vimarsh (feminist thinking) is so often dismissed as something “women do” amongst themselves. Amidst all of this I also carry the deep privilege of being an upper caste city woman who did her doctoral studies in London.

What are your thoughts on the current climate on non-English knowledge and production?

I can only be cautiously hopeful! But I am among a growing number of academics and thinkers who realise that we can’t just concentrate our attention on just one singular language. I’m aware also of what, say, Hindi knowledge production entails as well – because of this, I do feel we need to think (and work) much more multi-lingually, and also commit ourselves to what we read and produce in languages (like Hindi) that have a large readership.

When you read multilingually, you realise that while the Hindi middlebrow world is a very important one – both because Hindi is a very oppressive and a deeply nationalist language – it is important to take cognizance of Hindi. But unless and until you read Hindi alongside Urdu, alongside English, Gujarati and so on, you will not be able to find the different ways in which women move through their universes. Magazines like Sarita were pioneering for women in this particular language. So I take care to say that it’s wonderful for Hindi readers to think in cosmopolitan ways but Urdu readers were reading so much more in so many wonderful, cosmopolitan ways, much earlier.

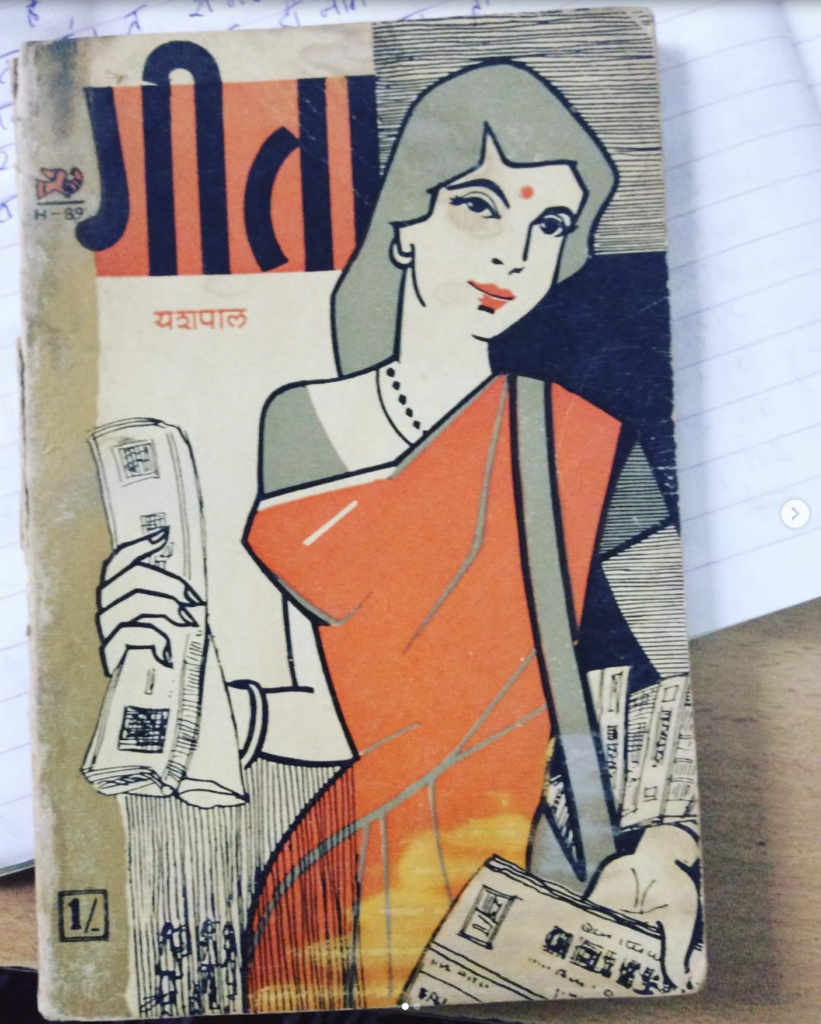

Your book cover and Instagram archive documenting historic images of women reveal a fascination with the imagery of women reading, and that too in public. What was your process of finding these images and how did people respond to it?

This project, on the visual history of reading, really came out of my despair to find a suitable book cover: I couldn’t find women reading at all in my magazines. That’s why I used Meena Kumari’s image in the book, reading at a [film] set in 1962. I find images of women reading fairly ubiquitous in the early twentieth century. However, they often only seem to appear on the covers of the magazines. For now, I understand it in this fashion: perhaps books and magazines needed to be pointed or marked out as women’s magazines, to encourage or educate a sense of reading for women.

Still, this bafflement led me to start this public-facing project called South Asian Women Reading.

The archive got immensely popular on X, but there were varied responses. A lot of people, including scholars and historians, were very enthusiastic because they thought about these images in the context of their own projects, and they also contributed from their own projects to this. It helped me contextualise further the images that I was trying to decipher for my own reasons. It also evoked personal memories: lots of people said we would like to share a photo of our grandmother reading, and they wanted to place their own family, their mothers or foremothers in history, as part of something that was happening.

Another intense feedback was that these pictures feed into people’s nostalgia, distancing people from the stories of women, as if it is some other life that now we are here to look at.

But a more bizarre response I saw was that people started using AI tools to lift the text that I have written in order to create a different reality of that text altogether. There’s an image of Debalina Majumdar where she’s photographing two family members in the 1940s in Bengal, standing reading a magazine. I wrote something along the lines of stopping time and how these women were making a statement by posing in a certain way. Somebody used AI and put up another post with the picture, with the caption indicating these women are protesting for the right to read. The family members of the women who were photographed took offence and posted online that this framing is incorrect. These images are made in a certain context. Sometimes these women are protesting, sometimes these women are being ‘destructive’ and claiming a space in public. Sometimes these are deeply elite women who are just enjoying life, as was portrayed here.

I’m not saying I have copyright on these images. I am crediting people and the magazines when I use them, and I myself don’t know the ethics of using AI for this. But I find it deeply disturbing that people are twisting the context of what it means for women to read. I also wonder then, what does it mean to place a digital archive on platforms that encourage quick consumption in quick bites, and separate the context from these narratives?

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.