From Caregivers to Data Workers: The Hidden Burden on Tamil Nadu’s Anganwadi Workers

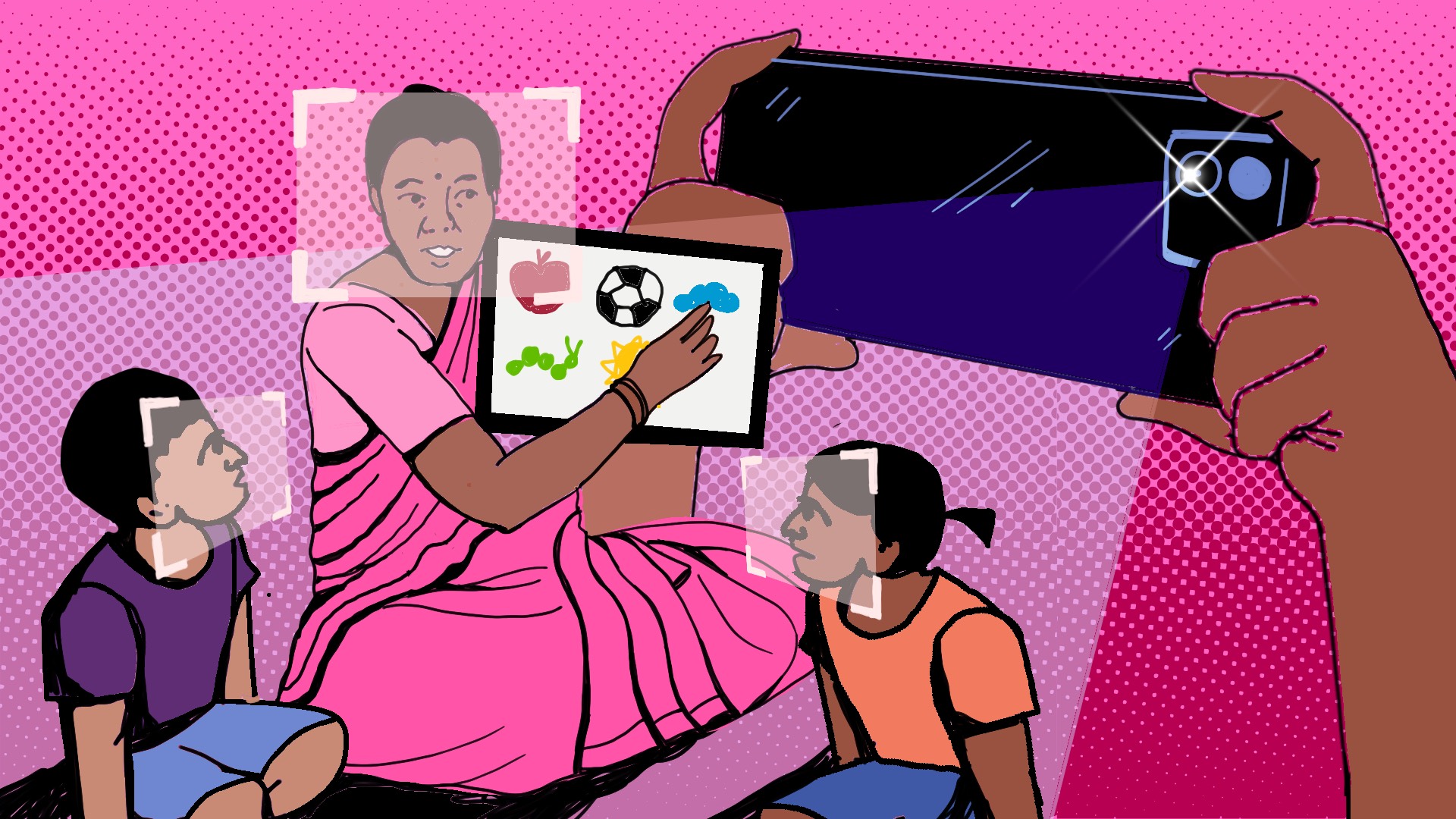

As beneficiaries become data points on the dashboard, Anganwadi workers in Tamil Nadu grapple with an overload of digital labor, being data collectors building a state’s health repository, and being subjects of surveillance

- Archita Raghu

A large part of Selvi’s working day at an Anganwadi centre in Chennai is spent on her smartphone. As her colleague jokes, if a parent were to peep in, they would think that the workers are whiling away the time they should be devoting to the children.

The truth, however, is that over the last three years Anganwadi workers across Tamil Nadu, have had their digital workload doubled. They have to manage two apps, both tracking the delivery of welfare schemes for women and children, one managed by the Centre and the other by the state.

The Centre’s Poshan Tracker app was launched four years ago under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS). A year later, Tamil Nadu launched its own tracker app for the schemes, named TN ICDS, because it found the central app inadequate for its own needs, as we explain later. Its use is not as intensive or frequent as mandated for the Poshan Tracker but it still adds up to the labour put in by the state’s Anganwadi workers.

Then a facial recognition system was introduced by the Poshan Trackers late last year. From capturing photographs of pregnant women and young mothers receiving Take-Home Ration (THR) for Poshan to uploading data on children’s nutrition on both apps, the digital tasks are relentless. It has resulted in not just a massive workload and duplication of data entries but also a never ending cycle of surveillance.

“Each day, I seem to be battling the Poshan tracker app,” says Selvi. Her first task as she enters her centre is capturing a group photograph of the children, squirming, crying and excited. This is meant to be evidence of the children’s attendance but while it does this, it also surveills workers like Selvi, their attendance and performance.

Selvi’s daily fatigue and war with technology begins with countless installations and uninstallations of the Central government app, introduced by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in March 2021, on her Samsung phone. She says she has to do this because the app does not pick up on her location till she uninstalls the app every day.

“I will be sitting here in the school but the app shows me 170 metres away due to a server issue. Finally, when I uninstall and reinstall it and the location and server work, we have to force these tiny children to keep their eyes open. If their eyes close, they don’t show up on the app,” says the senior teacher. According to the Poshan tracker manual, with geofencing, the app feature detects and verifies if the user is accessing the application within the Anganwadi center premises or a different location.

It is only when the group photograph of her 20-odd children is uploaded that Selvi can access the details necessary for her to mark attendance, take photos and finally proceed with her duties as a preschool teacher. Despite all this work, Selvi herself has no access to the data she uploads. Comforting a crying child while handing two eggs to a parent, she points to two new updates on family surveys, and children’s malnutrition.

“These updates were not there yesterday and now I have to allocate time to navigate them,” she says,

We had reported recently on a photo-backed attendance app launched by the municipal commissioner of Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar city for all corporation workers including ASHA workers. While TN’s tracker apps do not require photographic evidence of attendance, workers point out that it surveills them equally effectively.

“Our attendance is the opening of the app. If we want to take leave, we have to input our dates for leave on the app as well,” says an Anganwadi worker.

The overwhelming idea behind this rising digitisation of health work is the belief that you cannot trust paper records anymore and only digital technology is reliable, says Sreya Dutta Chowdhury, a Ph.D. scholar whose research is focussed on medical anthropology at the International Max Planck Research School. “It is about surveilling at the local level; and this has been the trend since the advent of Aadhaar. It is being used for monitoring and replicating bureaucratic relations [between workers and officials]. It becomes less about welfare delivery. There’s this narrative that everything before tech was corrupt and that photos cannot be forged; there’s this push for systems where you can control at a distance,” she explains.

It is not just the responsibility of gathering good data that now falls on local healthcare workers. “The responsibility of creating the surveillance state, the grounds of surveillance, is being devolved down to this level,” says Sreya. “The state makes the health worker, the lower rung of power, responsible for creating good data. This is how they circumvented the issue of data privacy. They say the data is used by health workers.”

Why Multiple Apps

Apart from maintaining 16 registers, workers like Selvi in Tamil Nadu’s 54,439 centres work on uploading similar data on height and weight of children, details on pregnant women, and lactating women on both apps. BehanBox has previously written about Poshan Tacker, and how the digital shift has overburdened workers.

Why are two apps needed to track the same parameters? State officials say they found the central tracker limiting.

“POSHAN tracker does not allow us to run analysis on any state-specific schemes. It only has line data (like attendance for example) and not trends, so we export that data onto TN ICDS to get block level data and make interventions,” says an ICDS official, who preferred not to be named. And not using POSHAN is not an option.

Reetika Khera, associate professor of economics at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi, has been critical of digitisation linked with welfare of delivery schemes for years. She believes that the data collected by the central ICDS app might not be passed on to the states. “It is possible that the workers continue to upload on the central app because fund flow may be linked to data entry on the central app,” she says.

The TN app is an amalgamation of data from the Poshan tracker, but it also has data on stunting and malnutrition on children aged 0-6. Introduced in 2022, it is also used to track schemes like the nutritional intervention of ‘Uttachathai Uruthi Sei’, which monitors nutrition of mothers and children.

Supervisors can access the data on the TN ICDS app, which comprises data from the health department, from the pregnancy and infant cohort monitoring and evaluation (PICME) portal, says a Child Development Project Officer in the state. Most workers we interviewed say they input data into the state app at least once a month, others say they do it even less. A year ago, when Behanbox had met the workers they had said the pressure to use this state app had lessened.

A recent CAG report found discrepancies in the data of total number of beneficiaries in TN ICDS and the Poshan Tracker and the Monthly Progress Reports. “These inaccuracies led to inconsistencies in the data relied upon to monitor the implementation of the scheme,” the report says.

Facial Recognition System

Workers have already flagged issues of posts laying vacant, and poor infrastructure, and data adds to their woes. While Selvi’s work hours formally end at 4 pm, she spends until 10 pm (until the app is no longer accessible) navigating sketchy signals, bad servers, and glitches to finish uploading details on both apps. “I began wearing glasses after these apps were implemented. Headaches and watering eyes are a regular occurrence,” she complains.

As BehanBox reported earlier: “The Poshan Tracker app has unequivocally changed the nature of the job done by Anganwadi workers – they say they have gone from being primary caretakers of pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children to being the government’s data collection agents.”

Uploading data has become a daily struggle for the workers in the state, and their most recent struggle has been the facial recognition system on the Poshan Tracker app. Pushed as an efficient means of surveillance, the manual says this method aims to “reduce fraud and improve service delivery by verifying the identity of beneficiaries”.

However, the data repository for ICDS does not stop at FRS but is intrinsically tied to and pervades all tasks of Anganwadi workers — from headcount, providing hot cooked meals, to monitoring the nutrition of children.

Through the day, workers are required to keep their location on. “There is the government narrative that these apps are for health workers themselves to have a systematic record of their work and tap into cash incentives. There’s this idea that they are data stewards at the local level, as they are the ones who are using the data to deliver efficient health services and create a record of their own work,” explains Sreya.

Waiting Forever – For OTPs

Earlier this year, Anganwadi workers were tasked with implementing the FRS of the beneficiaries with two-factor authentication for pregnant women and lactating mothers to avail of the Take Home Ration. On the Poshan tracker app, they were tasked with registering beneficiaries with their Aadhaar card and mobile phone number; each time a beneficiary appears to collect this nutritional kit during the first five days of the month, the long wait for an OTP for verification begins.

“It depends on the server – how much time it decides to take, that is how long we take to take care of a beneficiary waiting for the OTP, it could take 20 minutes or a few hours. We wondered – how much does one need to do to just collect one kit?” says Selvi.

At the first instance of a beneficiary registering for THR, a worker has to wait for three OTPS – one after photo capture, one for eKYC verification, and one to verify the profile on the Poshan Tracker app, says a supervisor who did not wish to be identified. The next time a beneficiary visits, they have to wait for one OTP, while dealing with faulty phones, and poor connectivity.

In March, protests erupted across the state, with Anganwadi teachers opposing the facial recognition system. Even beneficiaries reported regrets in signing up for the nutritional kits.

In a southern district in the state, *Lakshmi finds herself anxious every time her phone beeps with a notification. In her district, she says several women do not receive these kits as their Aadhaar cards are not linked with mobile numbers. This came after the Centre urged states to link Aadhaar cards of beneficiaries for them to avail of the free-food programme. In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the Aadhaar was not mandatory for bank accounts, mobile numbers, school admissions but this verification persists.

“Why are we depending on a flimsy card and forgetting who we are working for? How will we ensure children receive their nutrition?” says a district secretary of the Tamil Nadu Anganwadi Employees and Helpers Association who did not want to be named.

The time she spent on her phone has doubled, she says, after FRS: “We are unable to serve the pregnant women in our district or truly spend time with the children. Our time belongs to the phone.”

Other workers told BehanBox the same – that they felt pressured to reach data targets rather than care for beneficiaries. But while the app provides an option to ‘proceed’ or ‘skip’ with FRS, the consequences of doing so have been problematic.

Digital Stamp For Integrity

A month ago, Anganwadi worker *Pushpa told BehanBox she received a visit from an official. “I hadn’t uploaded photos that day and the official came and asked me whether I was distributing the kits, and accused me of forgery.” This kind of distrust has led to a rise in anxiety among Anganwadi workers about adhering to FRS guidelines.

A CDPO admits to the problem. “It doubles the work of an Anganwadi worker and is an extra burden. There is pressure for the 100% completion of the FRS. If a worker chooses the skip option, sometimes we have to go talk to them about this.”

Anganwadi workers like Selvi say they are hurt that the State does not trust them to deliver services without the elaborate digital process. “The reason we took this job was that we love interacting with and working with children. No matter how hard the day is and the apps we juggle, you see their smiles, and hardships seem to vanish,” she says.

The rise in digital surveillance comes with the assumption that the refusal to use it or inability to use it is tantamount to non-compliance or deception, points out Sreya.

The FRS was mandated across states by the Centre in August 2024. But Tamil Nadu asked for time till June to complete it. “Currently, we have reached 52% of completion — with Erode at 99% and Sivagangai at 10%. We don’t have control over the app and the Poshan tracker team needs to address issues (on bad servers or connectivity),” said an ICDS official, who preferred not to be named.

The incentive for juggling these apps, and uploading data per month is Rs 500 for the Anganwadi worker and Rs 250 for the helpers. If targets are not met, incentives are cut for the worker, and helper. The TN ICDS app provides no incentives.

According to the Poshan tracker website, a worker is eligible for an incentive if the following conditions are met: attendance for 21 days, finishes 60% of targetted home visits for beneficiaries (pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children between 0-2 years), and finishes 80% of growth monitoring of children between 0-6.

‘From Intimate To Bureaucratic’

Jayanthi*, a Chennai-based worker, counts on her fingers the digital tasks on hand: Poshan Tracker, TN ICDS app, Aadhaar to crosscheck ID details, a block-level app for registering voters, and a few Whatsapp groups for coordination. “We do this work despite conducting home visits for children and mothers, carrying weights and scales,” she points out.

The focus on recordkeeping now outweighs core functions of caring for beneficiaries. Reetika deems it “bewildering” that a photograph uploaded on a portal through an app reassures officials that schemes are working smoothly. “A photograph on an app is as useless as an entry in a physical register that the child has been fed. Neither guarantees that the child has in fact been fed. For that one needs to see a change in social norms and work culture,” she argues.

But is data not an effective way to ensure nutrition outcomes? Theoretically this could be true, Reetika says but adds: “Even before these technologies appeared, Anganwadi workers could use ‘growth charts’ to refer a child with poor growth to the nearest health centre. Granular monitoring would be useful if you actually had the intention of using that data to remedy outcomes, but that intention is not entirely clear in these digital initiatives.”

In ‘Counting to be Counted: Anganwadi Workers and Digital Infrastructures of Ambivalent Care’ Azhagu Meena S P, Palashi Vaghela, and Joyojeet Pal found that a tech-based model “cares about people as numbers on the dashboard of the ICT-based Real Time Monitoring system of ICDS; it professionalizes the idea of care to simultaneously individualize and anonymize those being cared for. It shifts the notion of care from that of concern to indifference, and intimate to bureaucratic”.

Jayashree Muralidharan, Secretary to the Department of Social Welfare and Women Empowerment, admits to the problems but also points to the advantages of digital tracking. “We need to be able to see whether the ration is truly reaching the beneficiary. There is a need to bring in some discipline and be sure that there is no pilfering. The government of India needs to streamline the distribution process. We are aiming for 100% but understand the technical difficulties on the ground,” she says.

On the issue of beneficiaries being excluded on grounds of non-linking of Aadhaar or not wanting to be photographed, the ICDS official told BehanBox that the basic process is meant to eliminate ghost beneficiaries. “The Poshan Tracker team said they are working on the process where a beneficiary’s relative can pick up THR. The system is not foolproof.” In the next few months, the state team is on hold to see if the app is helping or hindering the beneficiaries and workers.

But one of the critical shortcomings of the data collection process here is that the Anganwadi workers are not made aware of what the end purpose is. How do these apps store this population’s data? How does it travel up the hierarchy? Who does the monitoring? What changes are brought about on the ground with this data? Few have the answers.

“With technology entering care work, it’s less to do with welfare than to do with display of success of governance. It’s the politics of display on ground — that these many kits are delivered and these many pregnant women helped. This is a spectacle of success they have to prove with every project,” says Sreya.

*Names changed to protect identities

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.