[Readmelater]

Farming Against Time: For Bhil Women, Natural Farming Comes at a Cost

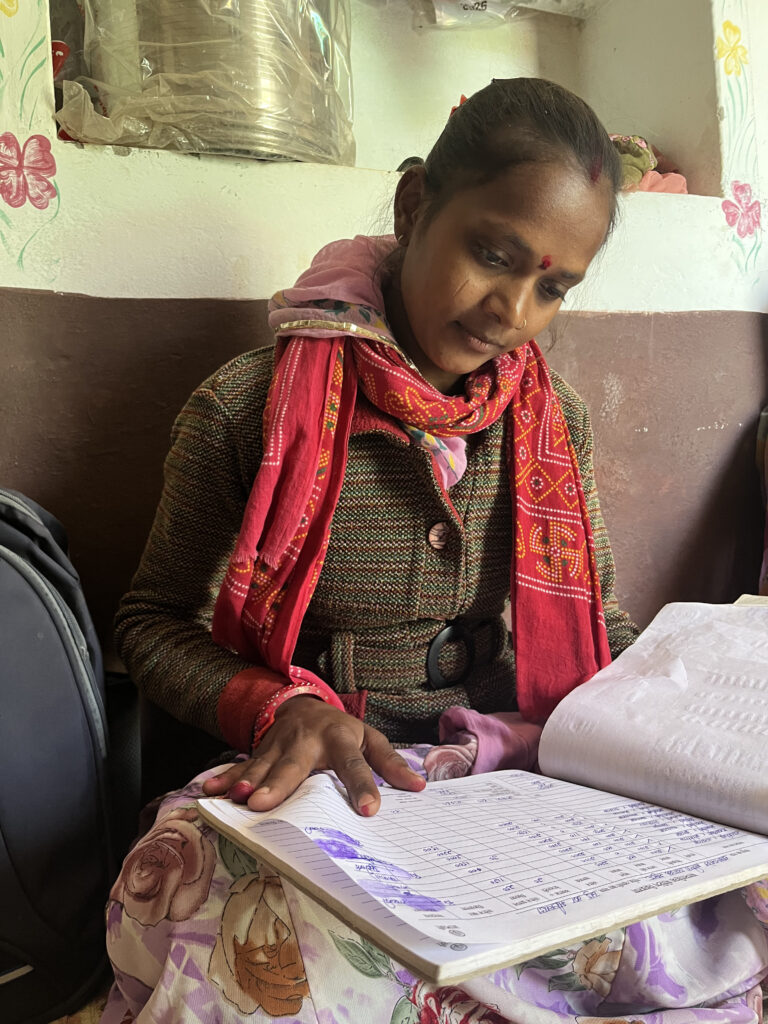

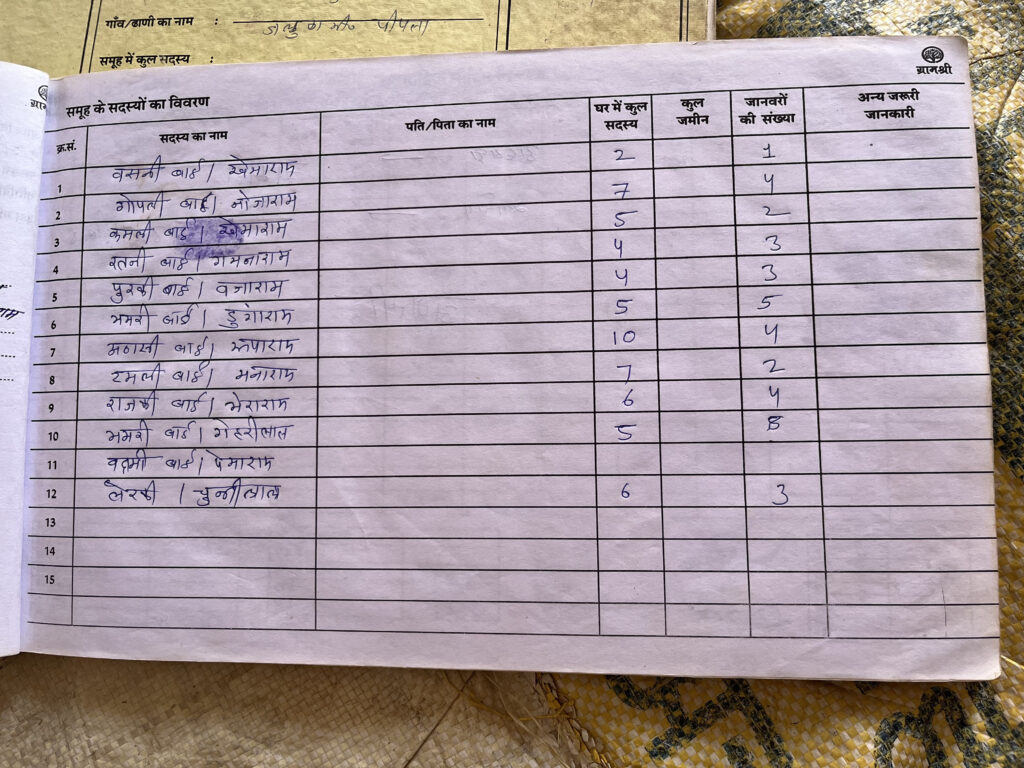

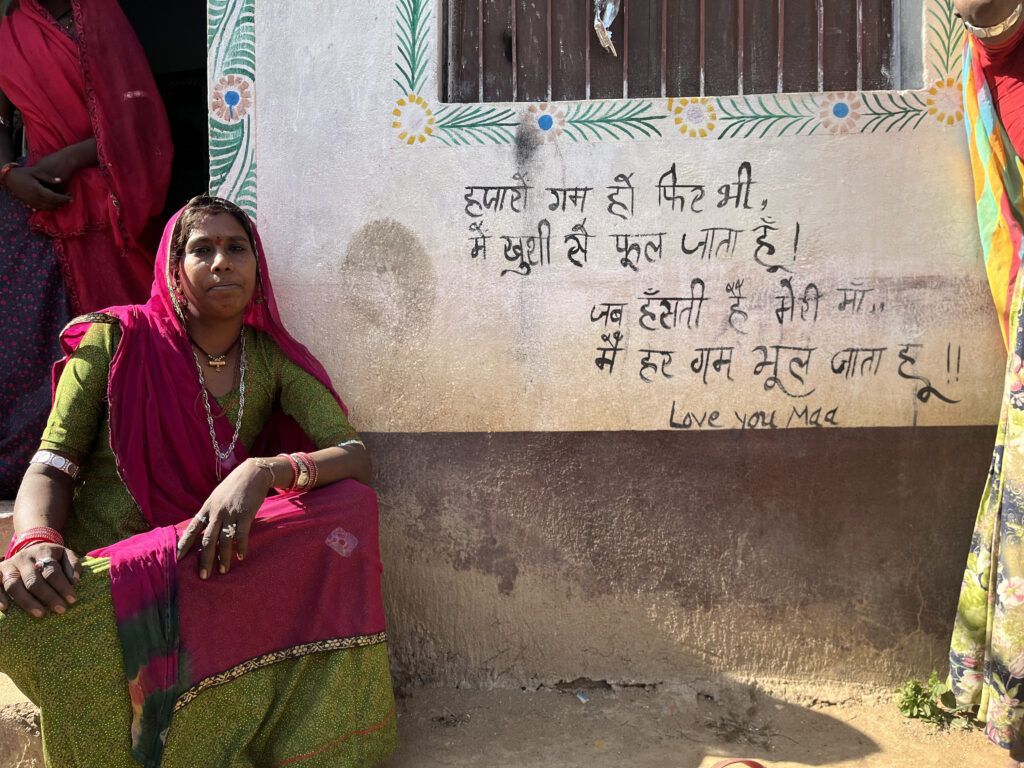

Bhil Adivasi women members of the SHG sit in a ghera (circle) at Ratnibai’s house for their monthly meeting, which begins with a prayer and song followed by discussions around natural farming/ Mansi Vijay

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.