In Sagonia village, there are around 50 Kanjar households and every family here has faced arrests under the excise act, our investigations show. Men, women, and even children have been subjected to legal action and there are allegations that they have had to endure police brutality while in custody and outside.

“I don’t sell liquor even when we don’t have secure jobs or employment under MNREGS,” says Kailasibai Kanjar, 50, who has faced multiple incarcerations. “Our community is labeled as criminal by the police. They raid our homes whenever they want, disrupt everything, throw away our belongings, even food and toys of young children.”

The Vimukta women we interviewed said they brewed mahua liquor only when they are driven to despair by the absence of livelihood options. They usually brew up to 2-4 litres for sale and keep the rest for their families to be consumed during festivals and community events.

“When there is no work and my family goes on the verge of starvation, I sell 2-3 litres of mahua liquor. With an investment of Rs 500-600, I make a weekly profit of around Rs 500-600—roughly Rs 100-150 a day, though some days I earn nothing. But the police torment us endlessly. Even when I’m not selling anything, they barge into my home on mere suspicion. They demand bribes, and if I refuse they seize my belongings, ransack my kitchen, beat me, and force me to flee,” said Bharatibai Kanjar.*

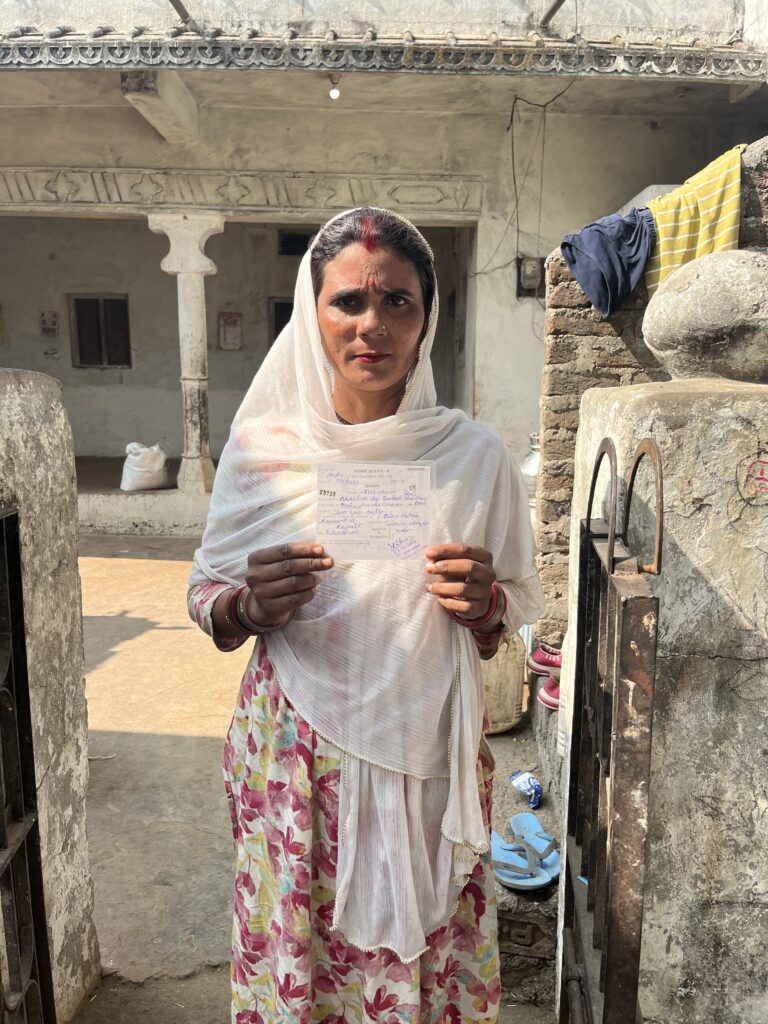

All the women and men we interviewed from Sagonia village in Guna allege police brutality – beating, extortion, casteist, verbal and sexual abuse, confiscation of property and intimidation of children. All women of the Kanjar community in this village say they have been incarcerated at least once. All of them are out on bail and have no idea about the current status of their cases.

Quite a few women in their 50s, such as Kailasibai, have multiple FIRs against them. Kailasibai is still waiting for a verdict in a case that was registered against her eight years ago in Chachoda.

“In January, I was taking my son, who had a fever, to a doctor in Raghavgad village when they stopped us in the market and began yelling at me. They demanded Rs 5,000, but I only had Rs 600, which I handed over—it was all I had. I had to get my son treated at a government hospital because the police took all my money. But even that wasn’t enough for them. They threatened to arrest my husband if I didn’t pay the full amount. To save him, I was forced to take a loan from a private moneylender at a steep 5% monthly interest rate,” says Poojabai Kanjar.

Women from different NT-DNT communities have to take up loans to bribe police and they languish in debt traps, Behanbox has reported.

Fearing arrest, Poojabai’s husband has stopped going out. “Our men don’t go to work fearing police action without due legal process and evidence,” says Priyanka Kanjar.

Behanbox has sent a questionnaire via email to the district excise office of Guna about the manner in which the act is implemented in the state. This story will be updated when we receive a response.

CPA Project’s research shows that the implementation of the excise Act is largely castiest. Its study of 5,62,118 arrest records from 20 districts of Madhya Pradesh and 540 randomly selected first information reports, shows that 56.35% of those arrested belonged to marginalised communities – SC (9.87%), ST (21.53 %), OBC (15.64 %) and Vimukta (6.86 %).

Says lawyer and co-founder of the CPA Project, Nikita Sonavane: “When the police act under the excise act, they seize and sell accused persons’ vehicles, even before the trial is concluded. Later, if the accused is acquitted, they receive no compensation for their lost property. Bail in these cases are rarely granted by lower courts, forcing many to approach the High Court at great expense—an unaffordable burden for Vimukta communities.”