Postscript: The People and Process Behind the BehanBox Story

Our monthly newsletter with all things behind the scenes.

Want to explore more newsletters? Our weekly digest BehanVox and monthly Postcard invite you, the reader, into our newsroom. Subscribe to our work or visit our Substack channel for more.

It was with a befuddling question at our weekly BehanBox meeting that Archita Raghu’s incisive story on Tamil Nadu’s family planning agenda took shape – could there be a link between the periodic shortages of the morning after pill in the state and CM Stalin’s strange call for young married couples to have children as quickly as possible?

Ummm, we said, amidst collective head scratching, what is the connection? But first, let us rewind to how it all began. About five months ago, Tamil Nadu woke up to the news that a government drugs panel had recommended a ban on over the counter sale of emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs).There was a furore over what seemed to be fear-mongering over a pill that has been declared safe and nearly 100% effective with few side effects by the WHO. Then with a half hearted response from the state that there was no ban on the pill, the debate calmed down.

But it is the worst-kept secret among the state’s health circles and sexually active people — there have always been periodic shortages of the pills in the state. Contrary to popular perception it was not just the young, elite and unmarried who were hit by these shortages. It was also a mother of two, desperate to avoid a third pregnancy; it was also a couple who just did not have the resources to raise a child. It turned out that pharmacists were not sure what the social and moral connotations of stocking ECPs is. Some thought it encouraged promiscuity, others believed that it was an abortion pill and had to be taken under a doctor’s guidance. Unsure of facts, they adopted the simplest trick in the book — made the pill less available.

Exactly what was going on? It was with the intent of seeking clarity that Archita sought an interview with Archanaa. At a Chennai cafe, they started a discussion that went beyond an official interview; they discussed concepts of morality, sex, pleasure, and women’s bodily autonomy and the state. At a point, Archita recalls Archanaa asking her: but what about chief minister Stalin’s exhortation to young married couples to reproduce here forthwith?

It was an unexpected angle to what was a basic story on a pharma crisis. How was it that a state with a long history of liberal and modern thinking on reproductive and sexual rights – going back nearly 100 years actually – suddenly sounding cautionary about the perils of pleasure and also turning pronatalist?

Back at the meeting, we decided and not without some scepticism, that these two seemingly disconnected issues could be probed.

Archita spoke to S Anandi, professor at Madras Institute of Development and author of A Question of Silence? The Sexual Economies of Modern India. What emerged was a story that is as old as the hills — every time a political, cultural or social issue gathers heat, the first place the battle is fought is over the bodies of women.

By 2026, because of its successful family planning drive and dwindling birth rate, the South is expected to lose seats in the Lok Sabha, its share declining from 23.7% to 19%. It was now up to the women, per Stalin, to hold up the state’s place in India’s polity.

“All of these anxieties are pinned onto women’s reproductive choice and it has a direct implication and is not to be taken only from the point of view of delimitation. Women’s autonomy has to be addressed as the medical world continues to entertain the idea that birth control has to be a must for all women and it is (rooted) not women’s freedom,” explains Anandhi.

With that we could pull disparate strands of the story together on how even a state with an acclaimed record of women’s rights could actually seek a reversal of its progressive triumphs. You can read the story here.

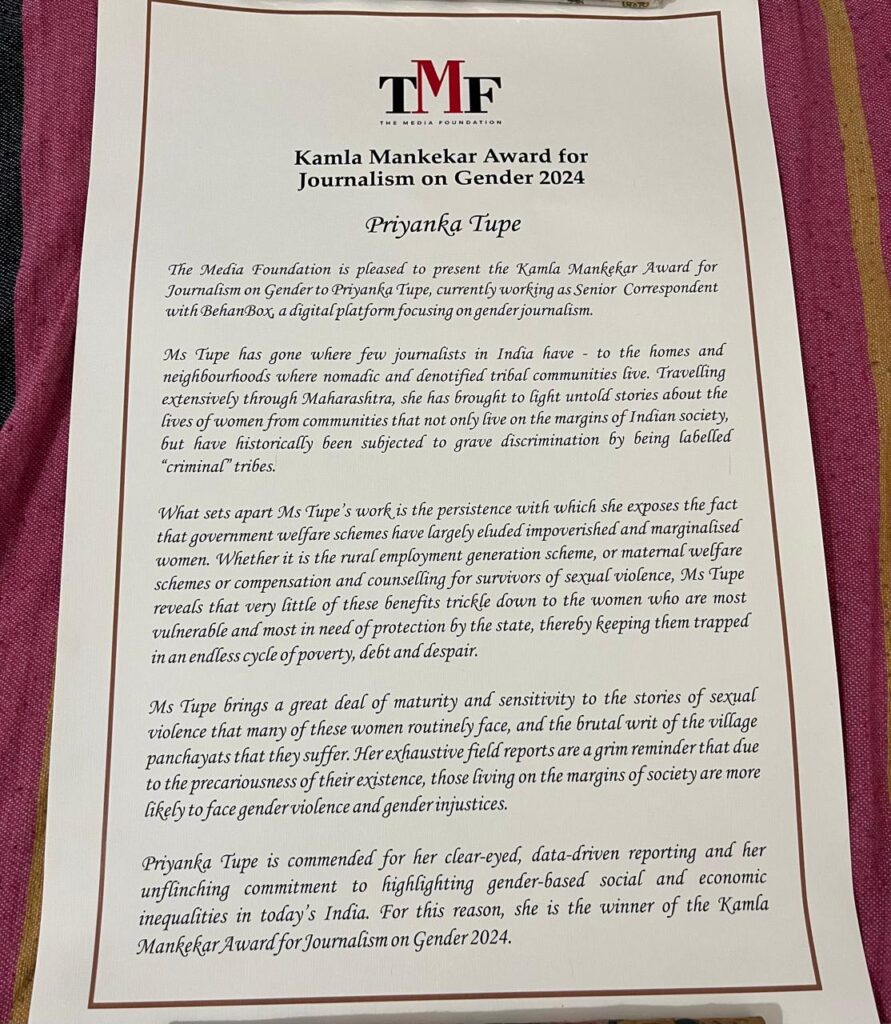

March also brought in moments of great joy for our small, distributed newsroom. Priyanka Tupe, our Maharashtra based senior correspondent, was recently awarded the inaugural Kamla Mankekar Award for Journalism on Gender by The Media Foundation that also honours an outstanding woman media person every year with the Chameli Devi Jain award.

Her citation read: “Priyanka Tupe has gone where very few journalists in India have – to the homes and neighbourhoods where nomadic and denotified tribal communities live. Travelling extensively through Maharashtra, she has brought to light untold stories of women from communities that not only live on the margins of Indian society but have historically been subjected to grave discrimination by being labelled as ‘criminal’ tribes.”

The award honoured Priyanka’s sustained reportage on the NT-DNT communities. As part of our series ‘Marginality and Justice’, we unearthed that the legal avenues for women from the NT-DNT communities were difficult to access. Rape survivors found it hard to claim the rehabilitation schemes meant for them. Then there was the tyranny of the Jaat Panchayats, community kangaroo courts that penalised them in insidious ways for defying caste norms despite a law. But we also met incredibly brave women like Sunita Bhosale and Dwarka Pawar, once victims of the diktats of these courts, who are now actively campaigning against them. This year, Priyanka picked up the issue once again, this time reporting from Madhya Pradesh on a disturbing trend of suicides among Pardhi women due to constant encounters with institutional violence, bias and poverty.

“I always felt that their stories remained largely overlooked, with mainstream media failing to provide them the space and attention they deserve,” she says. During her election reporting trip to Vidarbha during the General Elections in April 2024, she stumbled upon a disturbing truth — women from Phase-Pardhi, Pardhi and Dhangar communities were migrating long distances, some as far as Odisha and West Bengal, leaving their young children behind in the care of their elderly grandparents and older siblings, some as young as 10, because there was no work for them in their own villages. A scheme that was meant to guarantee work was deliberately excluding the women who needed it the most, keeping them in a cycle of intergenerational poverty. This story made her angry, she recalls. This was not an isolated issue – it pointed to a larger systemic faultline connected to their historical ‘criminal’ tag with colonial roots, now outlawed, that continues to shape their reality. And it was necessary for us to focus our attention on the structures that perpetuated these inequalities despite constitutional guarantees of equality for all its citizens.

Our Delhi based colleague Saumya Kalia was also one of the nominees for the award for her excellent reportage on the contestations of India’s gig economy.

These are difficult stories that need a great deal of emotional, intellectual and financial investment. But they are essential. There are many layers to peel, many angles to follow, many lives to uncover, and many links to make between poverty, exclusion and systemic inequality. But at the end of the day, as a newsroom, we need to ask hard questions of the state — why are people kept unequal? How do we tie news stories back to patriarchy, justice system, and the state? In asking these questions, we take great care to keep the interest of the communities whose stories we tell, at the centre of it all.

What's Coming

How do we make our stories travel from our desks to the corridors of power? How can our stories create impact beyond readership? How do we escape the tyranny of the big tech that decides what deserves attention while devouring our own? We’re grappling with these questions and have realised that the answer lies in building our own community — of readers and doers who care, and collectively build knowledge systems that are a public good.

- The ASHA Story is one such archive for public good. You might have heard rumblings on our social media. For 20 years, ASHA workers have worked tirelessly to make our public health systems robust and equitable. They’ve done this without decent pay, labour rights and above all, the necessary recognition. We want to both honour their contribution to nation building and archive them for posterity. And we want to do this with you, our readers. Help us build this archive through ideas, contributions and support of any kind. Write to us at contact@behanbox.com.

- Gender Audit: A young woman’s rape at Pune’s Swargate bus station brought forth the everyday reality — how unsafe public places were for women and gender diverse people. The public and media discourse around it once again followed the familiar script — blame games, shrill voices and even victim shaming. As a newsroom, we decided to take a novel approach — a gender audit of bus stations in all the 36 districts of Maharashtra. We wanted to arm ourselves with data to make a strong case for state provision of safe spaces of public transport. And once again, we are doing this as a community exercise. Members of the community will audit these bus stations on several parameters like access to services, information, safety parameters and even lived experiences. We are partnering with Jhatkaa, a campaign organisation, to take these findings to the public as well as those in power.

- Women, leisure, and work: There is a gap in the official Time Use Surveys. They did not capture the granularities of how women across castes and professions spent their time, the relationship with their work, and indeed what counts as leisure. In a bid to capture the fine nuances and affective elements of time use, we are building a project to understand these with a mix of approaches that are both journalistic and semi-ethnographic. Keep your eyes peeled.

That’s all for this month’s Postscript, Behans. Our eyes, ears, hearts, and inboxes are always open for your thoughts. Write to us or comment below.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.