Why Women Refuse To Give Up The Battle To Save Vadhavan, Site Of India’s Largest Port

Despite 30 years of local resistance, the government has pushed through the approvals for India’s largest port. Behind it lie systemic efforts to dismantle special protection given to an eco-fragile area

- Shreya Raman

“It is better that they kill us, poison us and throw us away,” said 41-year-old Manisha Ambire, screaming to make herself heard over the din of an ice-grinding machine at the fish-processing station in Dhakti Dahanu. “They would have to if they want to build the port. Because none of us will leave and let this happen.”

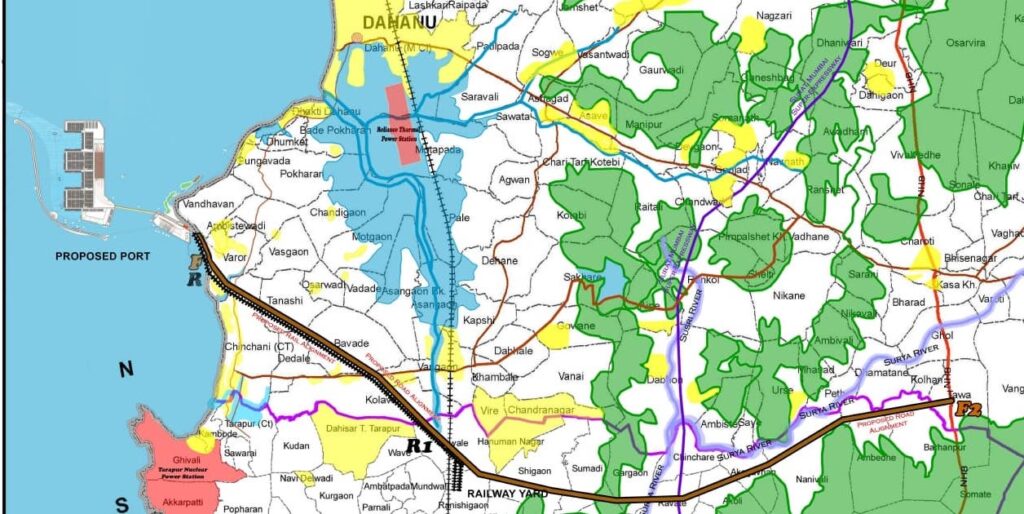

Manisha is among the hundreds of fisherwomen from this village in Maharashtra’s Palghar district protesting the construction of a port over reclaimed land in the sea just off Vadhavan village in Dahanu taluka. The port, touted to be India’s largest, will be spread across 17,471 hectares, one-fourth the size of Mumbai. It will include 16,900 hectares of port limit and 571 hectares of acquired land for road and rail linkages and is being jointly built by the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Authority (JNPA) and the Maharashtra Maritime Board (MMB).

The project is going full steam ahead, despite strong resistance from the local fishing, farming and Adivasi communities. The move to build the Vadhavan Port started 30 years ago and these decades have seen fierce protests by local residents to highlight its potential impact on the lives of those living in this ecological sensitive region. Dahanu, one of the first taluka in the country to be notified as an “eco-fragile area”, is the only green belt between the polluted industrial areas of Vapi in Gujarat and Boisar in Maharashtra.

Yet the port is only one among a slew of public infrastructure projects – a bullet train, freight corridor and an expressway – that will divert thousands of acres of land for construction work leaving its ecology fragmented. Multiple governments have tried to dilute the protection given to Dahanu to get these projects approved, as we explain later.

The approval for the Vadhavan port is the latest in this trend. Locals say the port will destroy their homes and their livelihoods and those of the thousand others who are indirectly earning from the fishing industry.

“We don’t want the Vadhavan port. We don’t want the facilities, we don’t want the lakhs of rupees of compensation. We will work hard and fill our stomachs. We don’t want to move anywhere else and we don’t want the money,” said Manisha.

These ports are part of the Indian government’s larger push to further corporate interests through large-scale projects, disregarding the environment, lives and livelihoods of local communities. In Great Nicobar, a 166-sq km mega-infrastructure project will likely uproot one crore trees, destroy local biodiversity and hit the lives of the uncontacted Shompen community. In Chhattisgarh, around 95,000 trees have been cut for coal mining in Hasdeo Arand forest, one of India’s largest contiguous forest tracts.

Our continued reportage (here, here, here and here), uncover how these projects are impacting fragile ecosystems across the country, alienating people from their lands and livelihoods. Women, who have largely been at the forefront of resistance movements to protect these ecosystems face systemic police crackdown, threats and incarceration.

Coastal Communities Fear Port Projects

Studies at contentious port projects show their impact on the livelihood of fishers. Ports impact water quality, coastal hydrology and cause beach erosion and a decline in fish catch and biodiversity. The breakwater, a significant structure constructed to protect the harbour from ocean waves, causes adverse effects – shoreline changes, water stagnation and sediment deposition, which leads to rehabilitation of fishing communities and reduced catch means reduced incomes.

All the local people we met in Dahanu said that they would not let the port be built. Across villages, there are angry banners and wall writings that say “Ekach zidd, Vadhavan Bandar Radd (we are adamant, the Vadhavan port project should be scrapped)”.

In addition to concerns of impact on livelihoods, researchers and environmentalists for years have raised concerns about the environmental degradation that the port will cause, which include shoreline changes, decline in biodiversity, increased pollution and sea level rise. They also said that the environmental impact assessments of the port project underestimate its real impacts, as we detail later.

Port authorities maintain that the project will bring employment opportunities to the area with minimal impact on the environment. But evidence from another contentious port project, the one located in Vizhinjam in Kerala’s capital Thiruvananthapuram, disproves these assertions. There too the state government had dismissed apprehensions that the port would disturb the coastal ecology or the livelihood of fishers. But now, four years into its construction, the sea has rapidly advanced into the coast, hitting the lives of local fishing communities.

Port, Protest and Politics

The plan to build a port in Vadhavan began in 1997 when the Maharashtra government awarded the Australian subsidiary of the British company P&O the contract to build a mega port. When journalist Narayan Patil, then a 50 year-old, heard about it, he realised that it would displace entire villages. He formed the Vadhavan Bandar Virodhi Sangharsh Samiti, a resistance collective spanning 30 villages in Palghar.

The Samiti, along with Dahanu Taluka Environment Welfare Association (DTEWA) and other organisations, approached the Dahanu Taluka Environment Protection Authority (DTEPA) with its objections while the P&O proposal was being examined. A year later, the authority rejected the port proposal and called the port “wholly impermissible” and “illegal”. It was then shelved.

In 2014, after the BJP-led NDA government came into power, the plan was revived and this time it included an alternative plan for the port to be constructed on offshore reclaimed land as a part of its Sagarmala Programme to “unlock the untapped potential of these [maritime] resources for port-led development and coastal community upliftment”.

A year later, the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT) and the Maharashtra Maritime Board signed an MoU to develop a satellite port for JNPT off Vadhavan coast. And since then multiple groups representing fisherfolks, Adivasi people and farmers have come together to voice their concerns. Massive protests were held locally, at Mumbai’s Azad Maidan and across the Konkan coast.

Women's Resistance

Phiroza Tafti, convenor of the Dahanu chapter of Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), an NGO, said women realise what the project will do to the future of the community, their environment and children’s lives.

“We will continue to protest till the end because the port will destroy our livelihoods totally,” said Rekha Marde, 48, a fisherwoman. Women – who are responsible for selling the fish while the men work at sea – have been an important part of these protests. “In fact, women are more involved than the men,” said Julie Tambore, 42, from Dhakti Dahanu.

Despite all this, the union government still went ahead and approved the construction of the port in June 2024 at a cost of Rs 76,200 crore. The prime minister did the Bhoomipujan ceremony at a ground near the Palghar collectorate, 30 km from the site of the port.

“Is Vadhavan Port going to be built at Palghar?” asked Manisha. “He should have done it from Delhi, why take the effort to come all the way here? They look at it from there and do not see how many people are going to die here.”

In 2019, people from Vadhavan and Varor villages boycotted the state assembly elections. The women Behanbox had interviewed in Dhakti Dahanu, last September, had predicted that the BJP would not win in the area in the 2024 state polls. Of all the six constituencies in Palghar district, the ruling Mahayuti coalition did not win in the Dahanu, where a CPI(M) candidate prevailed.

Long Struggle, Now Splintered

In another fishing village that Behanbox visited, there was palpable rage at not being heard. A group of people surrounded this reporter and said they were not interested in being interviewed. “Why have you come now? Where were you when we were on hunger strikes?” said one person.

The struggle against the port has been so long that people say they are exhausted. One woman pointed to a little girl and said: “I have been protesting against this since I was as big as her. And I have given so many media interviews but none of them have seen the light of the day.”

The long haul has also meant the protest movement has been fractured. Up to a point, said Phiroza, they could maintain the momentum. “But, then one person came and said that they are getting a contract for a quarry so they are stepping out,” she said. And many others who got contracts or other opportunities too gave up the fight.

She also said that many farmers whose children had migrated to cities and countries were apprehensive that they will not be able to sell their land because the notification doesn’t permit land use change. “They were worried about their future. So we lost their support to some extent.”

In the second village that Behanbox visited, one person said that a local leader they trusted had “switched sides”. “We have no hope,” they said, “The people that we trusted have betrayed us.”

Steady Weakening Of Green Authority

In June 1991, Dahanu was provided special protection by the environment ministry and five years later, in 1996, the Supreme Court directed that a special authority be constituted to protect the area. And so, the DTEPA was formed.

This authority has been critical in holding a thermal power plant in the area accountable for its pollution and installing pollution-control mechanisms and in scrapping the initial Vadhavan Port proposal. But ever since the authority was formed, political parties and industrial groups have been trying to denotify Dahanu and disband the authority, states this paper by Geetanjoy Sahu and Armin Rosencranz.

But DTEPA maintained a strong stand against this pressure, said Madhushree Sekhar and Geetanjoy Sahu in ‘Community-based Environmental Governance and Local Justice’, a chapter in the book Global Civil Society 2011. This independence came from the fact that the body is not under government control and is answerable only to the Supreme Court, as per this 2009 report on India’s Notified Ecologically Sensitive Areas.

The authority was first given a year’s tenure which was extended 15 times until 2002, each time only for 2-6 months. The funds for the authority were erratic. The union ministry also tried to scrap the authority, twice – once in 2002, when it approached the Supreme Court to end it on the grounds that it had completed its work. The court dismissed the plea. Then again the ministry approached the court claiming that the authority was superfluous and proposed a monitoring committee instead.

Since the death of Justice Dharmadhikari who was the chairman of DTEPA, the attempts to foil the authority intensified. Five years ago, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) declassified ports, harbours and jetties as “industrial activities” and two months later, the environment ministry said that these activities would be permitted in eco sensitive areas.

In February 2020, the union government gave an in-principle approval for setting up the port and in October the ministry granted the terms of reference that formed the basis for environment impact assessment. The TOR also has a list of reports and certificates required for the environmental clearance, including an NOC from DTEPA.

While the ministry application to scrap the authority was being heard by the Supreme Court, an ad-hoc monitoring committee was put in place, which between November 2020 and October 2021 cleared infrastructure projects including the Mumbai-Vadodara Expressway. In December 2021, after environmentalists demanded, the government reconstituted the authority in February 2022 with former justice A B Chaudhari as the chairperson.

In May 2022, the JNPT filed an application with DTEPA for clearance for the port. But the first full-strength hearing of the authority since the new chairperson was held only in February 2023. In that meeting, one of the members, Shyam Asolekar, expressed concerns about the port and criticised the quality of key reports.

‘Environment Report Is Full Of Holes’

Asolekar said that the report by the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management which concluded that the environmental impact of the proposed port facility would be minimal was flawed. He said: “This is a curious report, prepared in two months, has some 20 objectives, and used secondary data.” He also pointed to other holes in the assessment report: “This document does not have dates anywhere. Why?”

Bhushan Bhoir, a Palghar-based marine biologist and organiser with the Vadhavan Vandar Virodhi Yuva Sangharsh Samiti, pointed to the fact that the initial National Institute of Oceanography (NIO) report said there is no coral in the region. “I started shouting that there is reef forming coral here and that too in large quantities. When I showed my research to the DTEPA members, they said that they have to go for a site visit,” he recalled. But the visit was postponed and before it could happen, in March 2023, three dissenting members, including Asolekar were replaced by the central government.

“Then, when the new members did the survey, they just took the scientists and JNPA authorities and did a single party survey [that did not include anyone from other organisations or local groups],” said Bhushan. “They asked me to come unofficially. I refused because then it will not go on record and they will tamper with the reports. Then they mentioned 3-4 solitary species in the report and wound up the survey.”

After this, the plans changed from an onshore port to an offshore one and requested the government to change the terms of reference. Through an RTI request, Bhushan said he found out that the authorities have not done any underwater survey at the location where they are reclaiming land.

While the EIA report states that there are no species listed under the IUCN red list, Bhushan’s survey of the area found that the area where reclamation will happen is the breeding ground for blackspotted croaker and bronze croaker fishes.

Despite all this, in July 2023, the authority gave the clearance to the port without even waiting for all the mandatory assessment reports. The clearance order was even signed by persons who were not members of the authority, said Debi Goenka, executive trustee of the Conservation Action Trust who has filed multiple key petitions in the High Court and Supreme Court for Dahanu.

“The [new] chairperson seems to be under the impression that he has to clear each and every project,” alleged Debi. “And he has been clearing each and every file that comes on the table and in most cases, without the knowledge of the members of the authority and without the knowledge of the public, in a totally opaque manner.”

In January 2024, the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board held a public hearing, despite opposition from thousands of villagers. The villagers said that the hearing was held 30 km away from the project site with an aim to restrict participation. The public hearing was abruptly adjourned at 5 pm by the Collector without hearing from all the villagers and fisherfolk. Even the minutes of the hearing were not prepared by the pollution control board at the venue.

One of Bhushan’s contentions was that the environmental impact and social impact assessments did not consider the impact of the shipping corridor on the fishing area. “I also wanted to say [at the public hearing] that an intertidal zone survey that was to be conducted by the Zoological Survey of India was pending,” he said.

Debi appealed the DTEPA’s decision with the High Court, which upheld the order.

Off Shore But Will Impact Dahanu

The Bombay High Court, while passing the order also said that since the port is being built offshore, it falls beyond the area of Dahanu Taluka and “within the domain of the Central Government.” But all the supporting infrastructure – roads, railway and storage – will be in the taluka, said Debi.

“The boarding and goods transporting will happen in the taluka, and also all the ancillary activities–housing, dhabas, restaurants, petrol pumps, repair shops, everything will be there,” he said.

The High Court order has been challenged in the Supreme Court and the next hearing is scheduled to be held on February 28, said Debi adding that no construction activity will be permitted at the site until then.

“First they got these other projects – to feed the port – approved and then came the port,” said Phiroza. When the union cabinet approved the port, it also approved a new highway between the port and the Mumbai-Ahmedabad highway, rail linkage to the existing rail network and the Dedicated Rail Freight Corridor.

In Maharashtra alone, 39,000 trees will be cut for the Mumbai-Vadodara Highway that will link JNPT with Vadodara in Gujarat.

Of the eight Talukas in Palghar district, six, including Dahanu are fully scheduled areas, while two–Palghar and Vasai are partly scheduled areas. As per the Panchayats (Extension of Scheduled Areas) Act, gram sabha consent is mandatory for any land acquisition in Scheduled Areas. But no consent has been acquired for these projects, said Sunil Parhad of Adivasi Ekta Parishad, a grassroots organisation built by Adivasi activists in Maharashtra.

In August 2024, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways put out a notification to acquire 361 hectares of land from 14 villages to build the highway connecting to Vadhavan port.

Since the Mumbai-Ahmedabad High Speed Rail project, colloquially called the bullet train, was greenlit in 2017, thousands of Adivasi people in the area protested against it fearing displacement. Despite the protests, by 2024, 100% of the land was acquired for the project.

While many Adivasi people have got the compensation, they are still struggling to survive, said Sunil. “The situation is very bad. When people’s land in the village got acquired, they started migrating into the forest patches where they have claims under the Forest Rights Act and building houses there. But then the forest officials started harassing them. Where will people go? After moving up the mountain, if another project comes in, where will people go?”

One of the major problems, Sunil said, is that people are not given land when their land is acquired. “The money that they get, they think it is a big sum but by the time they buy land and start building a house, they realise they don’t even have enough to finish it. Then they struggle to make ends meet and have to start doing labour work,” said Sunil.

Women’s Employment Will Be Hit

In just Dhakti Dahanu, there are 60-100 boats and each boat provides employment to 10-12 women, said Sheetal Marde, 41. “Once the boat reaches the shore, it is on us women to sort through the catch and sell it. We put in as much effort as the men do on boats,” said Rekha. Each woman who works for cleaning and sorting the catch gets paid Rs 200 for half day’s work and gets fish worth Rs 200-250.

The Social Impact Assessment (SIA) report that the port authorities have uploaded on the website says the port will lead to increased domestication of women. The report states, “At present women folk in the project area are equal partners with men in the fishing and agricultural activities. The land alienation of the villages and Sea Shore Custody by the management of Vadhvan Port may automatically induce the women folk to work within their houses. They are not equipped in skills to get employment elsewhere – other than agriculture and fishing allied activities.”

“We are uneducated people, we have studied till 10th-12th standard. Where will we get jobs? Our lives are completely dependent on fishing and that will be destroyed,” Rekha.

According to Julie Tambore, 42, each boat brings in business worth Rs 70,000-Rs 1 lakh, and these earnings are now threatened.

The SIA report has said that the port’s impact on the resources may also extend to the value chain, from harvest to endpoint consumer. It will affect the income to fish drying units, women vendors.

Lalita Tambore and Ranjana Bari, both in their 60s buy fish from Dhakti Dahanu and travel over 70 km to Bhayander near Mumbai to sell fish. “Our bodies ache but we survive based on the money we earn from selling fish. Our children are sitting home jobless so we have work at this age,” said Lalita.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.