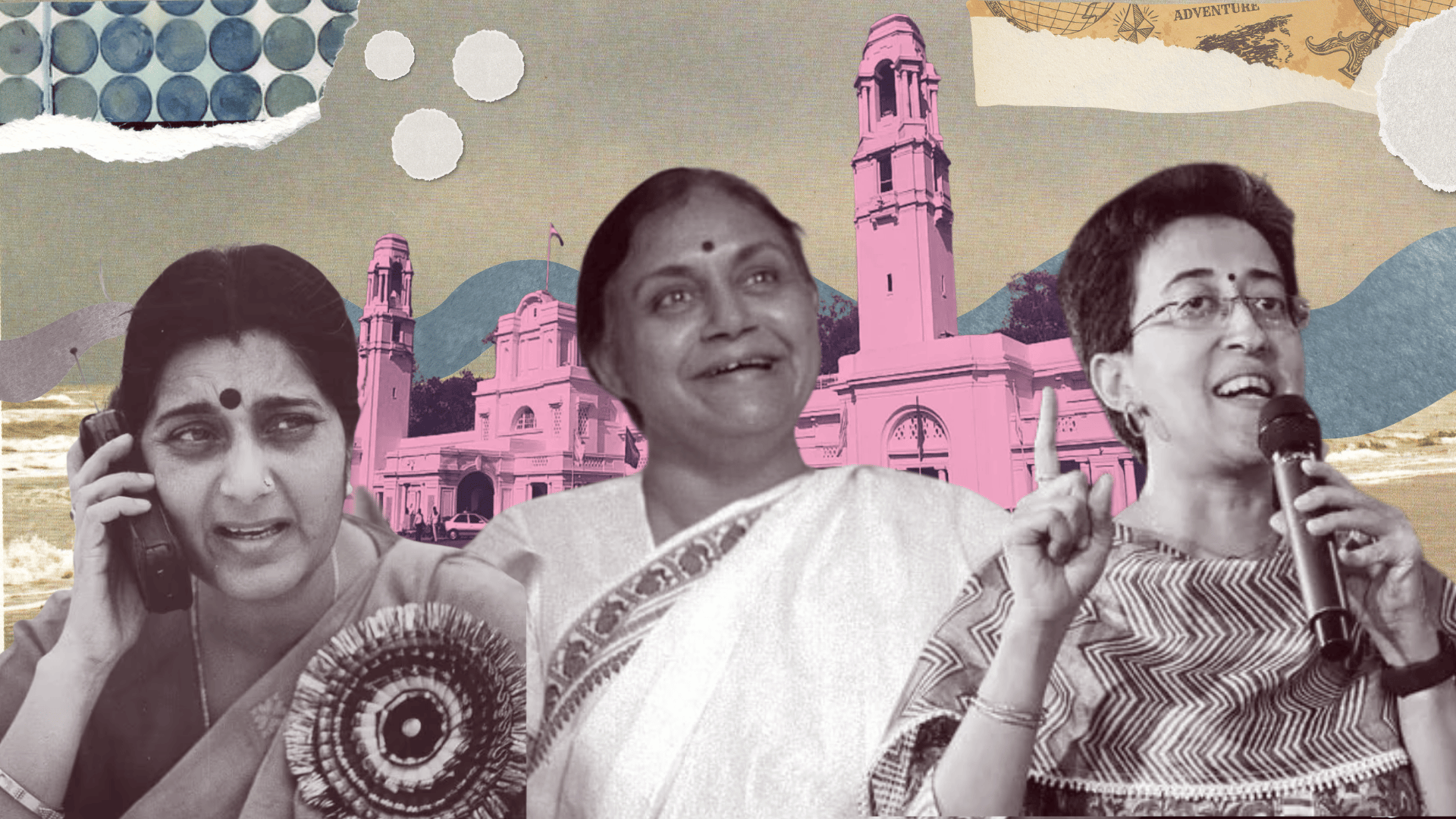

Three Women Governed Delhi, With Varying Success, But Each Left An Imprint

Sheila Dikshit was voted back thrice to office; Sushma Swaraj and Atishi came in briefly in times of political turbulence. But each made a place in the capital’s political history with their individual strengths

In a country that has seen only 17 women in the top post since Independence, Delhi remains somewhat of an outlier. It is the only state that has had three women chief ministers, one of whom also holds the distinction of being the longest serving female chief minister of a state.

There is Sheila Dikshit, credited with transforming the capital’s landscape. The other two, Sushma Swaraj and Atishi, will be remembered as Delhi’s first and youngest women chief ministers who came to power amid political turbulence.

Delhi as India’s political epicenter is unique in terms of women’s political representation, says Tara Krishnaswamy, a researcher on elections, policy, and gender justice. “A woman chief minister in Delhi is not the same as any other state having a woman leader or other kinds of representation [in jobs or public office],” she says. “A female head of a state who completes the term, who is powerful, who has left her mark breaks the myth that they are a dummy or a puppet… It sends a message that they are their own people, they have a mind of their own and their own style of governance.,” she says.

BehanBox pieces together the stories of the women who governed Delhi, placing them in the context of Delhi’s shared governance model, the performance of their parties and predecessors and the circumstances that shape women’s careers in Indian politics.

Sushma Swaraj, a Footnote in Delhi's History

“Sushmaji is known for many things, but not for being a ‘Delhi politician’,” says political journalist and author Rasheed Kidwai. Sushma Swaraj governed Delhi for 52 days, being its first woman chief minister and the last BJP politician to commandeer it. The veteran politician is remembered as one of the ‘most powerful women in the BJP’ and in national politics at large, but her time as Delhi’s chief minister is a ‘hazy memory’, Rasheed adds.

It was 1998, and the ruling BJP was facing a turbulence not dissimilar to what besieges AAP today. There were corruption charges against the then chief minister Madan Lal Khurana and BJP leader LK Advani and soaring onion prices had sparked discontent. The Delhi unit leaders resisted Sushma’s candidature for CM position, arguing that she was an ‘outsider’ who had previously been in the Haryana Assembly and would be unfamiliar to the city’s politics. Still, Sushma’s candidacy was pushed by the top leadership of the BJP, says Nistula Hebbar, political editor at The Hindu.

Between October 12 and December 3, Sushma reportedly set up a committee to manage onion inflation, per reports. BJP veteran Ved Vyas Mahajan praised her for inspecting police stations though law and order was not the CM’s domain. Sushma still lost in the 1998 assembly elections to a new entrant in Delhi politics – Sheila Dikshit.

Sushma’s legacy in Delhi is more about ‘nostalgia’ than ‘substance’, points out Rasheed. “She was given very little time, and by the time she could get a grip of things, the party was gone,” he says.

However, substance did mark her career in national politics. Sushma did not hail from a political background; her father was a prominent RSS leader and her family moved from Lahore. Swaraj’s political career precedes that of her husband Swaraj Kaushal who went to become the Governor of Mizoram. As a law student, associated with the RSS student wing of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, Sushma was politically active during the Emergency. She joined Kaushal, a lawyer at the time, in defending socialist leader George Fernandes in the Baroda dynamite case, and participated in the JP Narayan-led movement.

The 25-year-old entered the Haryana Cabinet in 1977 under the government headed by CM Devi Lal under fraught conditions: Lal deemed her “too young” and was reluctant to induct her, Swaraj herself considered resigning from the post before she was sacked for “not being competent enough”. Janata Party’s Chandra Shekhar later intervened and Sushma eventually stayed in the cabinet, handling portfolios like education.

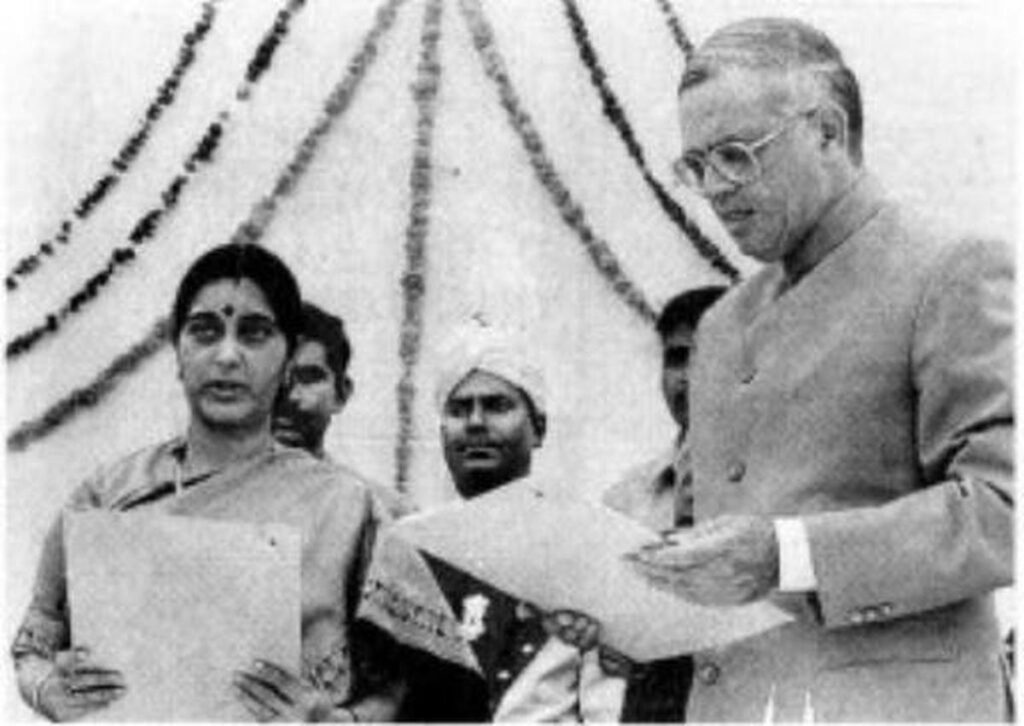

It was during the Ram Temple movement that she ascended the party ranks, was elected to Rajya Sabha and later Lok Sabha, and then quit her position as the Information and Broadcasting Minister in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government to be Delhi’s Chief Minister. After 2000 Sushma Swaraj held several portfolios in the Central Government, served as the Leader of Opposition between 2009 and 2014, and was the Minister of External Affairs until 2019.

As I&B minister, she believed satellite TV was a “social menace” and batted for a broadcasting legislation that protected “traditional” Indian values, including restricting scenes depicting sex and violence. Scholar Uwe Skoda in a paper highlighted how Swaraj “cultivated the aura of an ideal Hindu wife”, with a sindoor, mangalsutra, and very public participation in Karva Chauth. This image strengthened as she was pitted against Sonia Gandhi. Amrita Basu noted in an essay that Swaraj portrayed herself as a ‘swadeshi beti’ and Sonia as a ‘videshi bahu’.

But her time in Delhi comes as a footnote. “She was brought in towards the end when everything had been ruined by her predecessors. She was there to try and save a sinking ship… and she had to deal with a lot of stuff on a losing wicket,” says Nistula. “Sushmaji never got much of a chance really.”

Atishi, the Substitute CM

Until September 2024, Atishi had a lot going for her, says Tara. She had a reputation for being academically accomplished, and for shouldering the education portfolio, a cornerstone of AAP’s work in Delhi. But the researcher believes that she threw it out the window with a “cavalier action” during her first press conference as Delhi’s CM: Atishi sat next to an empty chair, used by party chief and former chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, and said she would run the city-state for the next four months “just as Bharat ruled Ayodhya by placing Lord Ram’s khadaun [on the throne] for 14 years”.

“It did not help her cause, or the cause of women…The minute you do that, you have erased yourself as a legitimate leader,” says Tara.

Atishi is a substitute CM, a ‘stopgap solution’ to AAP’s crisis, much like Sushma Swaraj. Corruption scandals have stirred anti-incumbency sentiments against the AAP; the resignation of the elected chief minister had left a vacuum just months before the national capital held assembly elections. Atishi will have completed about 127 days in office before Delhi votes.

Atishi has been associated with AAP since its early days but never started out as a politician. She studied history at St. Stephen’s College; pursued a Master’s from Oxford University on a Chevening scholarship and later studied as a Rhodes scholar. Her parents were former professors of history at the University of Delhi and have Marxist leanings. Atishi’s last name Marlena is a portmanteau of ‘Marx’ and ‘Lenin’. Atishi’s formative years were spent with books and “in-house classes on socialist revolutions”, an AAP aide told Al Jazeera.

After she returned to India, Atishi worked in the social sector, teaching and working on models for progressive education and self-governance in Indian villages. “I have been interested in being a participant in policymaking and education was one area that fascinated me,” she told Economic Times. She met AAP leader Manish Sisodia in 2010 and watched the 2011 anti-corruption movement from the sidelines. By January 2013, she was made a member of the party’s manifesto committee and was credited for being a “key policymaker and manifesto writer”, shaping AAP’s agenda on electricity, education, water, and roads before the 2013 Delhi elections. She contested the 2019 general elections from an East Delhi parliamentary constituency but lost to Gautam Gambhir. In 2020, she was elected as a Delhi Assembly legislator from Kalkaji.

Atishi has held almost 14 portfolios in the last 11 years, most notably education. In the book The Delhi Model, AAP worker Jasmine Shah wrote about Atishi spending nine months fixing the issues of poor sanitation in schools. Delhi has also been internationally recognised for its “happiness” and “deshbhakti” curriculum; it created its own state board to “replace the existing practice of rote learning”; and launched a network of Dr BR Ambedkar Schools of Specialised Excellence.

Atishi’s “perceived honesty” might help restore AAP’s image, wrote journalist Neerja Chowdhury.

But Atishi’s politics have slowly drifted towards embracing a ‘soft Hindutva’, noted Abhishek Dey in this profile of the leader in Al Jazeera. Atishi officially dropped ‘Marlena’ from her name in 2018, after Opposition leaders attacked her over unproven claims about her caste and faith. Some AAP leaders called Atishi’s decision a “survival strategy” since AAP does not endorse Marxism or socialism. Atishi was present at an astra puja during Navaratri; protested against demolition of Hindu temples; and has remained silent on instances of suppression of the Muslim community.

As a poll-time CM, she has to make her mark but not enough to threaten established party leadership, Neerja wrote in an article: a Dalit leader like Rakhi Birla would have been “difficult to replace” and veterans like Manish Sisodia and Gopal Rai could be future Kejriwal challengers.

But descriptors like ‘assertiveness’ and ‘politically heavyweight’ in Indian politics are rooted in sexist and misogynistic attitudes, argues Tara. “This branding [of being arrogant] has been applied to every assertive woman you can think of in politics, from Sheila Dikshit and Mayawati to Jayalalitha and Indira Gandhi. And when a woman accomplishes things in other ways – through dialogue, listening, or the power of suggestion – then she is deemed as a weak politician,” she says.

A civil servant in Delhi told BehanBox that while the new chief minister’s mettle in office has not been proven, she has been trying to make a dent: “Sheila Dikshit’s generation could function because largely the systems were responsive. Now, Atishi is functioning in an environment which sabotages functioning.”

Atishi is also disadvantaged by the timing of her leadership – when AAP is besieged on all sides, Tara says. Ministers representing the three most key portfolios – Kejriwal, Satyendra Jain, and Sisodia – are out of circulation. “She had to shoulder a very big burden,” says Tara. “You must give her credit for having stepped up…and having had to at least hold down the fort without massive bleeding.”

Sheila Dikshit, The Dev Anand of Delhi Politics

She is eulogised as the capital’s ‘last empress’. A ‘sculptor’ who changed Delhi’s face, a ‘smiling iron lady’ who led Congress to three successive electoral victories. Years after her tenure, and in the run-up to the Assembly elections, the Congress still banks on Sheila Dikshit’s reputation as an administrator but is reportedly shying away from using her face or her name.

Delhi saw flyovers and new buses and transformed into a global metropolis in the early aughts, but Shiela’s rule also brings to public memory the Commonwealth Games corruption scam and the apathetic handling of the 2012 Delhi rape case.

Political journalists like Rasheed Kidwai divide her tenure into before and after the 2013 Delhi Assembly elections. The first half is a success story. We have the image of a hands-on chief minister, revamping Delhi’s public transport and privatising electricity supply, and becoming India’s longest-serving woman chief minister. But the second half unfolded “like a flop story”, Rasheed says. Sheila lost the 2013 elections and her projected leadership in the 2017 Uttar Pradesh Assembly polls never materialised.

“Sheila Dikshit is the Dev Anand of Indian politics,” says Rasheed. “Dev Anand was out of sync, and so was Sheilaji from 2014 onwards,” he adds. Interestingly, Sheila in her autobiography confessed to crushing on Dev Anand as a teenager.

But some leaders manage to attain a larger-than-life presence in politics, seen through a nostalgia tinted lens and in the context of the failures of contemporary leaders. MG Ramachandram and Jayalalitha are memorialised as Tamil Nadu’s ‘visionaries’; NT Rama Rao still holds a ‘demigod’ status in Andhra Pradesh; Atal Bihari Vajpayee remains Delhi’s ‘titan’; Indira Gandhi is both a ‘messiah’ and a ‘monster’.

“Sheila Dikshit has transcended as a leader to achieve that kind of cult status,” says Tara Krishnaswamy.

Born into a family of civil servants, Sheila grew up on New Delhi’s tree-lined streets, moving from Rouse Avenue to Dupleix Lane and Queen Mary’s Avenue. It was a “disciplined but liberal upbringing, enjoying far more freedom than other girls of our age”, she wrote in her autobiography. She later studied history at University of Delhi where she met her future partner Vinod Dikshit, a bureaucrat and the son of Uma Shankar Dikshit, an Uttar Pradesh Congress leader in Indira Gandhi’s cabinet. Their marriage unfurled her political career, and she was encouraged to handle her father-in-law’s work after her husband passed away. In 1984, she was picked to be a part of Rajiv Gandhi’s cabinet, and served as a Member of Parliament representing Kannauj, UP. When Congress(I) split again in 1995 due to infighting, Sheila joined the breakaway Arjun Singh-ND Tiwari faction, and later rejoined the party in 1998 with Sonia Gandhi entering the scene.

“It was Sonia Gandhi who brought Sheila Dikshit to Delhi — a rank outsider in Delhi politics…Sonia Gandhi thought she would be able to manage Delhi well, and that gamble paid off,” says Rashid. She led the Congress to victory in 1998 with a significant margin, securing 47.75% of the votes against Sushma Swaraj. The victory was repeated in 2003 and 2008.

Observers say that she was an astute and articulate leader, with a keen knowledge of statecraft that made an impression on politicians and citizens alike.

Sheila Dikshit was conscious of the complicated nature of Delhi’s governance, says Nistula. “She was constrained compared to other chief ministers, she never once said that ‘this is not in my hands so I can’t do anything about it’. She always looked to what she could do within her limited remit — water, electricity, transport, roads, construction, PWD – and there, she did her best.”

Nearly 65 flyovers, including the AIIMS and Outer Ring Road stretches, were built during this time. The electricity sector was privatised, A new fleet of CNG buses descended on the city’s roads. Her policies ‘helped breathe elegance into Delhi’s heritage’.

But to Tara, Sheila’s work in reducing Delhi’s maternal and infant mortality rates, and working on human development indicators such as sex ratio is “her true merit of governance”. “Her legacy as CM also overlaps with the legacy of Narendra Modi as CM in Gujarat. The record of human development indicators in Gujarat – infant mortality rate, wasting and stunting, girls’ education – is absolutely shameful. She even outperformed AAP,” she says.

Civil servants speak of Sheila’s “attention to detail”. She would stop the car should she see a tree covered by an amarbel creeper, and ask her staff to prune it. A fused bulb on a streetlight, or a broken swing in a park, and the “whole NDMC would jump in response to act”, says Mahima*, a civil servant. The Bhagidari scheme, which engaged RWAs in tackling community issues, was her project. “The municipal staff was on its toes… Sheilaji used to say that New Delhi is like the drawing room of our city, and it has to be maintained.” When farmers or students held protests, Mahima recounts, Sheila asked staff to ensure clean public toilets and a rally space. “Hum democracy hain, hum aane se mana toh nahi kar sakte na (we’re a democracy, we can’t barricade our borders),” she used to reason.

Sheila’s shrewdness helped her in her dealings with the central government, even when the BJP was in power. “She didn’t let the political differences affect the development of the city. She worked with the BJP-led central government during her first term and completed ambitious projects such as the Delhi Metro. The present dispensation in Delhi can learn a lot from Sheilaji,” said Harsh Vardhan, senior BJP leader in an interview. Within Congress, she was considered a personal friend to Sonia Gandhi and her access to the Gandhi family reportedly resented by state party leaders.

Recurring feuds often put her at odds with Congress state leaders, including Kamal Nath and Oscar Fernandes, and some thought she was an ‘outsider’, ‘incompetent’, ‘authoritarian’ and ‘stubborn’. “She was surrounded by a lot of people who may not have wanted her there, but she used a lot of charm and tact to get her way,” Nistula says.

Sheila Dikshit in a 2019 interview spoke about meeting the LG at least once a week, where they would mutually come to an understanding. “Kejriwal might choose to fight the system and not serve the people. I chose the other way around,” she said.

Nistula recalls a story told by a Congress aide: Sheila Dikshit refused to call a press conference to lambast the Centre for holding up urban development. She reportedly told a colleague: if an elected government keeps telling people that it’s powerless, then the public will lose confidence in the system. Asahayita kabhi mat dikhao (never show weakness).

The Dikshit government did however preside over mass evictions of at least 2.5 lakh people when the city was overhauled for the Commonwealth Games. Rights agencies flagged grave violations – construction workers denied minimum wages, beggars arrested and banished from the city and street vendors denied the right to work. Rishi Seth, a Delhi resident, believes her policies “looked good on paper” but had “negligible” impact on people’s lives. New roads, flyovers and expanded metro lines overlooked pedestrians and cyclists, and added more stress to a ‘dilapidated’ drainage system that has remained unchanged since 1976. Unplanned urban development, growing vehicular pressure, and limited spaces created a vacuum in parking policy, which was exploited by parking mafias in the early 2010s. “Delhi no doubt became somewhat better for elites, but for others, the sense that the city slowly chips away at your dignity only solidified under her reign,” he says.

For others, her biggest failure was her reaction to the 2012 gangrape and murder of a 22-year-old medical intern in the national capital. Sheila Dikshit pushed back against public agitation, and deflected responsibility to the Centre. Many urged her to resign as an act of moral responsibility but she refused.

Observers do, however, speak of an air of dialogue, transparency and communication that flowed through Lutyens’ Delhi. Officers and ministers took out the time to brief people on the government’s point of view and the CM herself was accessible. “Anybody could walk in to meet her, she was very welcoming,” says Rasheed. The journalist describes her as the quintessential Dilliwali – she could be spotted having coffee at Khan Market, attending exhibitions, performances, and events at the India International Centre.

Political lore has it that she declined an opportunity to be in the Union Cabinet when in 2012 P Chidambaram became the finance minister, leaving the home minister’s post vacant. She is said to have retreated, citing the poet Zauq: “Kaun jaaye Dilli ki galiyan chhod ke.”

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.