To Be A Woman In Haryana Politics

In poll-bound Haryana, women’s political identity has been historically shaped by patriarchal, kinship, and gender norms. But their role in the protest movements of the last few years is making a difference

On September 11, it seemed as if a weariness had taken hold of Shweta Dhull, an activist and Congress worker from Kalayat, a town west of the city of Kaithal in northwest Haryana. Her X (formerly twitter) account was unusually silent – no fiery debates about unemployment, no dispatches from her turf in Kalayat. Had the endless days of enthused campaigning ahead of the Haryana Assembly elections taken a toll?

No, she said. She felt weighed down by disappointment. The ticket she says that was promised to her had been handed to a veteran Congress leader Jai Prakash’s son Vikas Saharan. The media had called her a ‘firebrand recruitment activist’ whose advocacy reached national politics. She walked with Congress leader Rahul Gandhi during his Bharat Jodo Yatra, worked on the party’s election manifesto, and helped “create an air and narrative for the Congress party in Haryana”, she says. “But they stole my dream.” She was exhausted, she said, fighting money, muscle power and sexism at every corner.

“Kya iss system mein ek aam insaan ki entry hain (is there a place in this for a commoner)?” she asked. “Especially a woman?”

To understand her sense of betrayal, one would have to step back and look at Haryana’s political cultures, past and present: the patriarchy, the firm hold of the Khaps or kinship clans, its political dynasties, and the more recent legacy of protests.

For women like Shweta, with no political inheritance to back her, contesting an election is a labyrinthine task marked by all-pervasive chauvinism. The candidates and experts BehanBox spoke with said that women have to often deflect comments about their appearance, gender roles, and character, even as they struggle to find the knowledge and the resources to make a difference. No one wants a thinking, confident, bold woman as a political leader in Haryana because it offends the establishments of power as well as patriarchy, they said.

But there is a common thread of resistance binding the women who make it through. Before she joined politics, Shweta led protests, sat on dharnas, faced violence, and went to jail protesting Haryana’s many recruitment scams and widespread unemployment. Wrestler Vinesh Phogat, now contesting as a Congress candidate from the Julana seat, stood her ground on women’s safety in sports. Other keen candidates felt emboldened watching women join the farmers’ protest in large numbers.

This increased visibility has somewhat “dented” a male-dominated force, said Jitender Kumar, a professor at Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak. Haryana is an “inherently male society where women’s presence in public is not tolerated, which reflects in their politics as well”, he said.

Since its creation in November 1966, the state known for its skewed sex ratio has elected just 87 women to the assembly (575 women have contested polls in its history), and six women to the Parliament. It has never had a female chief minister. In the last 13 assembly elections since 1967, women have comprised only 7.62% of all elected MLAs. Women elected to office are often someone’s wives, daughters, or daughters-in-law, functioning as proxy representatives, Jitendar Kumar pointed out.

In a social setup where women’s mobility is restricted and their presence barely tolerated, women candidates are stepping into the election maidaan to see and be seen—as women. But they are also political beings with a desire to effect change.

‘Why Give Tickets to Women?’

At the Kurukshetra University, Santosh Dahiya sat in the staff room, fielding queries from students about timetables and signing permission slips. She now chooses to stick to academia and social activism in her role as the chief of the women’s wing of Sarv Khap Mahila Panchayat, but was once a known face in politics. She contested twice as an Indian National Lok Dal candidate, before it was split due to infighting among the powerful Chautala clan in the state.

She recounted the scepticism when she entered politics. “Mahila ko ticket? Yeh stage pe chadhegi? Yeh bhashan degi and hum sunenge (you will give a ticket to a woman? Will she clamber onto a stage? give a speech and we will listen)?” she said, mimicking the cynics, her voice dripping rancour. This hostility and lack of confidence leaves women dejected and desperate, she said. “Voh hataash hokar laut jaati hain apne ghar mein (they return home in dismay),” she added. Women’s presence is now ‘tolerated’ in rallies, but they have to stick to the margins of political spaces, she pointed out.

A 2021 analysis by Triveni Centre for Political Data showed the number of tickets allotted to women in the 2019 assembly elections fell across all big parties, including the Indian National Congress, Bharatiya Janata Party, Indian National Lok Dal, and Jannayak Janta Party (JJP). Women were less likely than men to secure a ticket if they contested independently or without strong political backing. ”The sluggish growth is indicative of an organisational bias against women candidates in political parties,” the study concluded.

Santosh faced resistance from her party cadre when she was given a ticket. When she visited Beri town in Jhajjar to campaign, she found no support from the local cadres of her own party. Doubt crept in. “I thought politics is not for me, or I’m not made for it,” she remembered. She offered to withdraw her candidature, but the JJP leader Dushyant Chautala told her “Hausala rakh (keep your spirits up)”. She managed to win 20,000 votes from the area in three months.

Jagmati Sangwan, an activist with All-India Democratic Women’s Association, agreed that political parties prefer male candidates. “Women’s participation in politics as a worker, mobiliser, participant, and voter is increasing, but this doesn’t reflect in the leadership. Decision-making bodies continue to be dominated by men,” Jagmati said. ECI data suggests the ratio of eligible women voters to male voters is the highest since 1978; at the same time, there are 100 women in the fray this year, fewer than 108 in 2019 and 116 in 2014. Among the major parties, Congress has given tickets to 12 women, followed by AAP and BJP who have fielded 11 and 10 women politicians respectively. The splintered JJP and INLD have entered seven women each. 40 women are contesting as independent candidates this year.

Scholar WH Morris-Jones wrote that the traditional idiom of politics in India continues to favour male-dominated systems. There is no better case study than Haryana. Here, to secure a ticket a woman needs family support, funds, safety and network.

For families here, women’s lives are still twined around the pillar of community honour. ‘Bezati karaogi, ghar mein baith jaao (stay home, you will dishonour us)’ is a common refrain. When Arati (name changed) returned home after a day of canvassing, she learned of a neighbour’s disparaging comment to her husband: “Your wife is going around begging for votes”.

In contrast, Haryana’s Akhadas or wrestling arenas are rare sites that offer visibility and movement to women. Wrestling allowed them an opportunity to exist outside social parameters of morality, an opportunity they could use to compete for big medals and later seek government jobs. But in politics, women are faced with moral limitations every day, on every corner, as they move around the village. “People are sceptical about [women] canvassing boldly. This is a political culture where money power, muscle power, and all kinds of manipulative strategies are dominant”, making women unfit to manoeuvre political spaces, says Jatinder.

An Amnesty International report in 2020 found that during the 2019 Indian elections, at least one in five of the 1 million hateful mentions women politicians received on X were sexist or misogynistic. Some included rape and death threats. Experts agreed that this vitriol affects the courage of women politicians and shapes popular perception about them.

When Vinesh Phogat’s candidature was announced on X with a photo of her shaking Rahul Gandhi’s hands, online trolls passed offensive remarks. There were quips about the image on a Hindi television channel: “Yeh haath aise pakda hua hai, kya pata iss baar Rahul ka mauka nikal jaayega (she is holding his hands as if he is going to get ‘lucky’).”

This misogyny is also visible in the nature of the questions women deal with on the election trail. Shweta topped her school, has a masters degree in biotechnology, appeared (albeit unsuccessfully) for Haryana’s civil services examinations, and has led movements against corruption and exam malpractices. Still, she finds herself fielding more questions about her husband and marriage than on her politics or electoral issues. “You have to answer all sorts of questions, listen to patronising ‘lipstick-bindi’ comments. And if a woman becomes popular, her character is questioned.”

Shweta wants to bring in free coaching for entrance examinations, install street lights in villages, and develop a culture of education to combat Haryana’s growing addiction crisis. “If I had an MLA after my name, I could do all of this and more,” she said.

The question of family honour limits the sphere a woman politician can inhabit. Critical political decisions are often taken in contexts that keep women out – over alcohol, in covert corners, and involving talk about money and social clout. Women rush home to wrap up domestic care work while men network, said Santosh. “Agar ghar ke kaam mein lage rahenge, toh bahar kaise jaayenge (if they stay wrapped up in their domestic responsibilities how will they step out)?”

A 2014 paper analysing women’s participation in the legislative assembly acknowledged these issues: “Domestic responsibilities, lack of financial influence, growing criminalisation of politics have made it more difficult for women to be part of the political agenda. Thus, Haryana politics retains its masculinity.”

Dynasty At Play

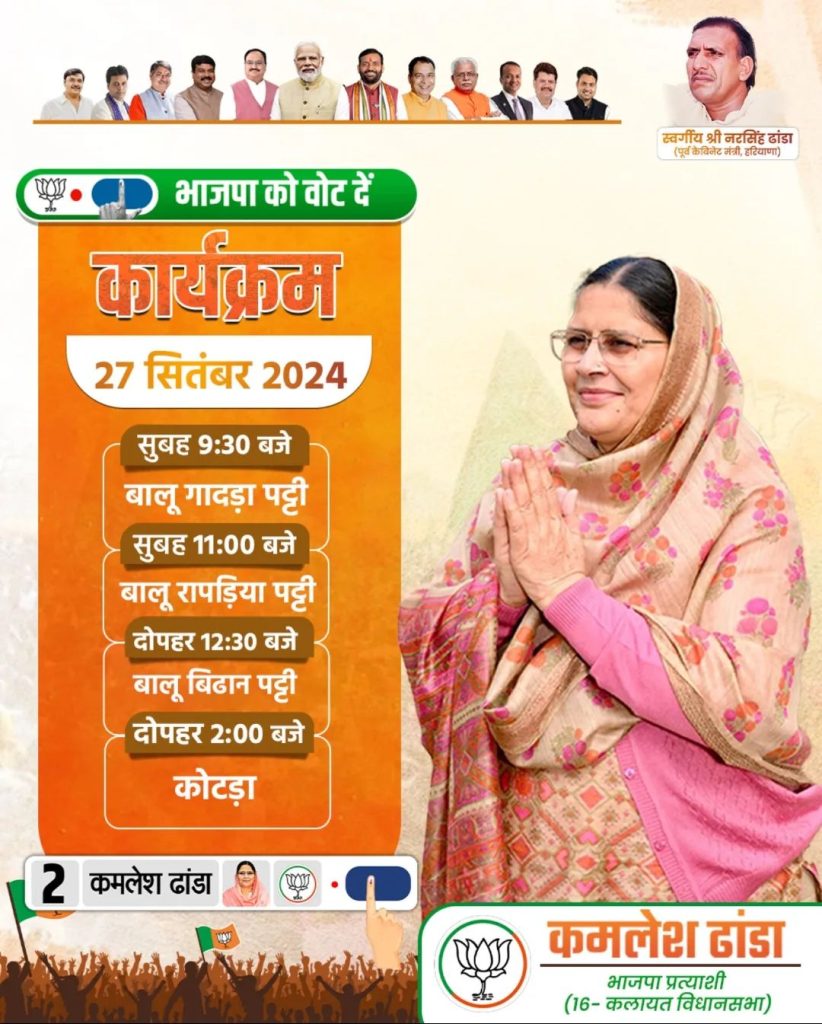

Across party lines, most women in Haryana politics come from political dynasties. Kamlesh Dhanda, BJP’s pick from Kaithal, was married to the saffron party’s Narsingh Dhanda. Indian National Lok Dal’s Sapna Barshami, contesting from Ladwa, is the daughter-in-law of Sher Singh Barshami, a former Ladwa MLA and trusted aide of the party who was convicted in the ill-famed JBT teachers’ recruitment scam in 2013, along with Om Prakash Chautala and Ajay Chautala (now associated with JJP). Ajay’s wife, Naina Chautala, was fielded as a candidate from Dabwali, after his arrest. Sudha Yadav who is contesting for the Badshahpur seat this time first got a ticket from BJP after her husband’s death in the Kargil War. Jitender says the decision was made because “there was no alternative from within the patrilineage”. Put differently, women receive political support only where there are no male contenders.

This political backing protects women candidates from vile character assassination, hooliganism and threats. Said Kanksshi Agarwal, a policy researcher and founder of NETRI Foundation, a tech-enabled incubator for women in politics, in a newsletter, “People who don’t have this kind of background hesitate.”

Days before the Kaithal ticket was announced, Shweta was indignant about a remark from veteran MP Jaiprakash Kalayat. During a rally he said he will “wear lipstick, bindi, and powder” if that’s all it takes to become a politician. Shweta felt she was being targeted. Why will women enter politics, and who in their family will encourage them if misogyny is normalised, she asks. “Tum mahila ko badha rahe ho, ya unki himmat todh rahe ho (are you trying to break a woman’s resolve)?”

Her online retort to Kalayat was sharp and poetic: “Kisi bindi wali ne tera ghar sambhala hoga/koi lipstick wali toh tere ghar mein bhi hogi/ma, bahu, patni, beti, poti–kya yeh mahila nahi (it is some woman wearing a bindi or lipstick who runs your home, is your wife, mother, daughter or daughter-in-law. Are they not women)?”

Patriarchy and Power

In Haryana politics, Chandrawati Sheoran is a storied figure. She became the first woman MLA in 1967 of Haryana state and went on to be elected 5 times and even served twice as a minister. She was also elected as an MP in 1977. A thumbnail view since then suggests a hopeful trend in women’s political participation: 11 women won in 2005, nine in 2009, 13 in 2014, nine again in 2019.

But this movement eclipses complex realities, said Jatinder. For one, women contestants for the Haryana assembly have never crossed the 9% mark in 58 years. Six of the state’s 10 Lok Sabha seats (including Sonipat, Rohtak, and Hisar which make up the Jat heartland) have never elected a woman MP. And two, “no women representative, either from Parliament or assembly, has acquired a dominant character in Haryana’s politics” due to the outsized influence of khaps, political families, and the race to capture the dominant Jat voter base.

Social scientist and historian Prem Chowdhry traces the traditional patriarchal structures before and after the Green Revolution in her 1994 book The Veiled Women. She argues that ghunghats (veils) in rural Haryana, a symbol of etiquette and honour, restricted women from participating in economic processes and ensured the continued dominance of patriarchal forces such as the khaps. These clan-based organisations are traditionally led by older male leaders from dominant castes, mostly Jats. Their strict marriage norms and pronouncements on gender roles preserve rigid patriarchal and kinship norms.

Khaps also hold immense political capital. They have the power to make or break a candidate, and an entire party’s future said experts Behanbox spoke with. Caste equations mean that any party looking to appease the Jat population (about 25% of the electorate), will have to remain in the good books of the local khaps.

“It is in this context that women remain on the margin,” says Jatinder.

The nexus of influence between power and patriarchy goes back to the 1960s. The politics of the agrarian state is said to be dominated by three Lals, wealthy, land-owning Jats: Devi Lal, Bansi Lal, and Bhajan Lal. Devi Lal, fondly referred to as ‘Tau (uncle)’, was a popular reformist farmer leader who founded the Indian National Lok Dal in 1987 as a party with a strong fidelity to “agrarian and cross-communal politics”. The fortunes of these families waned with time, experts said.

Bansi and Bhajan Lal’s third-generation successors are fighting on a weakened political turf, frequently shifting between Congress and BJP. The political heirs of Devi Lal, the Chautalas, are split across three parties after the INLD was split to form the Jannayak Janta Party.

Factionalism and defections aside, the emergence of the Hooda clan (and Bhupinder Singh Hooda as the chief minister) and BJP’s dominance since 2014 have skewed the dynamics against the Jat-dominated families. Here in 2024, decline of dynastic parties has created a vacuum that is slowly being filled by the BJP and Congress.

Negotiating Their Space

In this space dominated by patriarchs, women are negotiating their own political space. Jatinder says up until the second generation, women were not projected as worthy candidates and politics remained the sphere of men. Things have changed with the third generation leaders, where women are now picked to fill a gap: either that of succession or ideology. Devi Lal’s daughter-in-law Naina Chautala contested from Dabwali after her husband was jailed in the JBT scam; she won the election in his place. Her son Dushyant Chautala now leads the JJP.

Another example is Kiran Choudhry from the Bansi Lal clan. She won from the Tosham seat in the by-poll, after her husband Surender Singh died in 2005. Kiran’s daughter Shruti Choudhry has followed her into politics. Women thus end up aligning with the political aspirations of the family and preserve the legacy, Jitender said.

Women leaders are also fielded in Haryana to deal with ‘women’s issues’, say scholars. Instances like the wrestlers’ protest or rising crimes against women hurt the idea of honour that khaps hold up, and then women are encouraged to speak up. The Congress and BJP have also propped women candidates whose political identity may help the parties consolidate support within non-Jat communities.

But without meaningful women’s representation, the status quo remains. Santosh remarked that in the last decade, she has rarely seen a woman leader whose political idiom went beyond the party agenda to include gender reforms. During her first tenure, Naina Chautala reportedly never held a public meeting and limited herself to campaigning in home turfs of Sirsa and Hisar; she later started a gathering of women called ‘Hari Chunari ki Chaupal (a gathering of green dupatta-clad women)’ which is said to have increased women’s enthusiasm within her party. More recently, Naina spoke at a chaupal in Uchana last month, where she decried Congress politicians’ misogynistic and casteist remarks, and went on to point out JJP’s policies that respect women. She promised 50% reservation for women in teaching jobs if the coalition came to power.

Veteran Congress leader Kumari Selja is a rare woman leader who has managed to carve out a space for herself in Haryana’s male-dominated politics even though she comes from a political lineage. A former Union minister holding portfolios of housing, social justice, and education among others, the influential Dalit leader has long held chief ministerial ambitions. She holds considerable sway over the Sirsa and Fatehabad seats, two of the 17 seats reserved for SC candidates. Political observers, however, doubt if the Congress party would endorse her over Bhupinder Singh Hooda who has the support from the Jat community as her absence from the election campaign is interpreted as a sign of being “sidelined”.

Khaps that once upheld rigid, patriarchal norms are also examining their own role as well as making some space for women under particular circumstances. They have inducted women into their all-male circles and moved to eradicate the dowry and purdah system. In an EPW paper, scholar Ravinder Kaur argued that worsening material conditions were challenging Haryana’s patriarchal structures. Rising unemployment and inflation meant more off-farm work and thus migration, detaching individuals from community pillars such as khaps. This may eventually mean that younger people will have to negotiate changing economic and family structures, including gender roles, she wrote.

Santosh, who leads their women’s wing, says that khaps created women-led verticals because “they want to learn from women and educate themselves”. She contests the notion that they are against women per se but that they want to preserve their ideology, culture and most importantly their ‘honour’.

Women entering Haryana’s politics still must earn the support of khaps, say scholars and political observers within the state. Local khap leaders are supporting Vinesh’s political candidacy as they did with the wrestlers’ protest too. But Jitender argues that Vinesh’s case is different: the khaps extended support not because of her politics but because of a wounded ‘Haryanvi pride’ at the perceived ill-treatment, both on Delhi’s streets and at the Olympic stage.

However, parity in political representation can achieve limited gains if parties do not address the serious gender issues in the state – a skewed sex ratio, female foeticide and honour killings.

Protests And Political Socialisation

Growing up in Beri in the late 1960s, Santosh said she felt as though she was watching the world through a veil. She could only sense the excitement over Devi Lal’s farmer mobilisation. The khap leaders congregated near her home, but Santosh wasn’t privy to their dialogue.

She recalled an incident from when she was just 11: in a neighbouring family, the woman’s hands would tremble when she served her husband food. Once he threw his plate, fuming over an oversalted dal, and ran after the woman with a stick. “I ran towards the house, snatched the stick, hit him, and ran back home.” She was reprimanded but her mother, who wore a ghunghat too, later took her inside and quietly said shabaash, with an encouraging smile. “I was giddy–if my mother gave me a shabaashi, I must have done something right.”

In 1987, during a sports contest in Sirsa when she received a smaller sum of prize money than her male competitor, she asked questions. The news reached Tau Devi Lal. “He called me and said, ‘You have spoken up today about inequality, always do that’.” Santosh went on to spend two decades advocating for abolishing parda pratha, domestic violence, and honour killings.

Santosh said activism helped her reach people and understand their issues: if khaps and kinship decide the rules of entry, education, and engagement in Haryana politics, protests were an alternate route for her to sharpen her political gaze.

In 1996, seeing the apparent link between rising domestic violence cases and men’s alcohol consumption, organisations like the Janwadi Mahila Samiti led demonstrations demanding sharab bandi. Bansi Lal, a former chief minister and defence minister, formed the Haryana Vikas Party with the promise of alcohol prohibition. They formed an alliance to come to power, but their rise was primarily due to the women-centric issue and women-led activism, said Jatinder. Women mobilised many such movements, but remained on the margin, until 2020, when women descended on Delhi’s borders during the farmers’ protest.

It was the first time that Haryana’s women shared the dais with men.

‘Growing Political Assertion’

Haryana’s churn is reflected in the issues raised during the current Assembly polls: disaffection over farmers’ demand for a guaranteed minimum support price, the sexual harassment of wrestlers and their protest, and resentment over the Agnipath scheme for military recruitment. Moreover, the state has had one of the highest inflation rates in 2024.

A Hindustan Times analysis also indicates that the young here would rather enter the ranks of the unemployed than take up farming. And communal violence such as the riots in Nuh have sparked a yearning for change, said Rabia Kidwai, granddaughter of a former governor who is contesting from Nuh this year on an AAP ticket, the first woman candidate from the Muslim-dominated district.

Jagmati explained that the rising agrarian distress is leading to untenable conditions for communities, and compounding women’s work. “Scarce employment opportunities mean that children are not finding work. Young men are moving towards addiction, and as a result violence against women is increasing too…the overlapping crises has disproportionately shifted the burden on women,” she said.

Jitender is hesitant about interpreting women’s visibility in protests as an increased acceptance of their space in public. “Their presence is tolerated in case they are taking care of the kitchen, men and families … but no one wants to support a woman who aspires to play a dominant role in politics,” he said.

Jagmati is more optimistic. “Women saw other women join political spaces, expressing themselves freely on their issues and this builds confidence. It also makes them believe that politics can lead to change–even progress,” she said.

This assertion in resistance movements also allows women to access trust and support that are otherwise missing. Shweta, for instance, has been vocal about the impact of recruitment scams on young students and they in turn, were the first to voice their disappointment when she was denied a ticket.

In many parts of Haryana, including Julana and Balali, Vinesh Phogat has a cult following. “Vinesh ne aisa karnaama kar dikhaya jo kabhi nahi hua Haryana mein (Vinesh has shown us that the impossible is possible in Haryana),” said Sanjay, a wrestler and resident of a neighbouring village. Her fight against the political might and her feisty performance followed by the heartbreak at Paris Olympics have got her unequivocal support among men and women, khaps and clans.

In the Jat-dominated Julana, where she is contesting from, Vinesh’s campaigns centre around her role as ‘Julana ki bahu’ (the daughter-in-law of Julana, since her husband hails from there), while reminding them of her fight on Delhi’s streets as well as the Olympic stage.

The Indian Parliament passed the historic legislation in September 2023, promising 33% quota in state legislative assemblies and the Lok Sabha. The Bill will come into effect only after a delimitation exercise scheduled for 2026 that takes into account census figures. Had they implemented the legislation last year, states like Haryana could have seen a crop of empowered women, said Jagmati.

Shweta believes that the change, when it comes, will be driven by collective will. “An individual can’t do it alone. It takes a village, a family, to make a woman’s political aspirations come true.”

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.