More Women In India’s Labour Force Now But In Low-Paying Or Unpaid Work

The findings in the latest labour force survey indicate that the rising aspirations of educated rural women are not matched by opportunities in non-agricultural work

- Shreya Raman

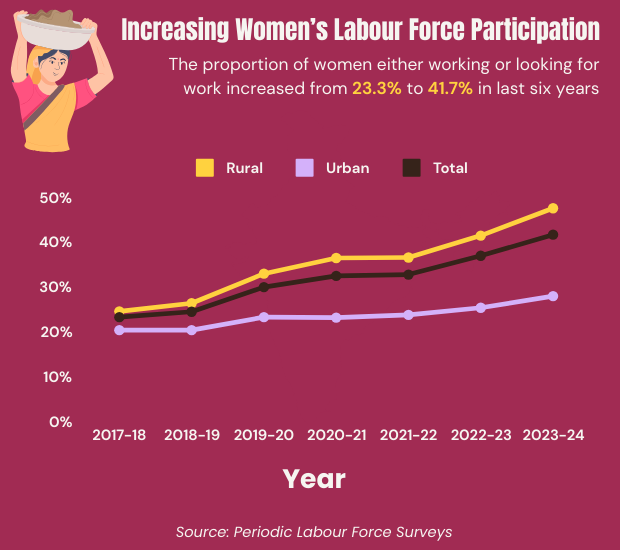

The proportion of women engaged in the Indian labour force increased from 37% in 2022-23 to 41.7% in 2023-24, the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) report released on Monday found. The report, released annually by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI), is the most crucial source of data on women’s employment in India.

The almost 5 percentage point increase – the highest in the last four years – has been driven largely by self-employment, which is not indicative of consistent or well-paying work, say experts.

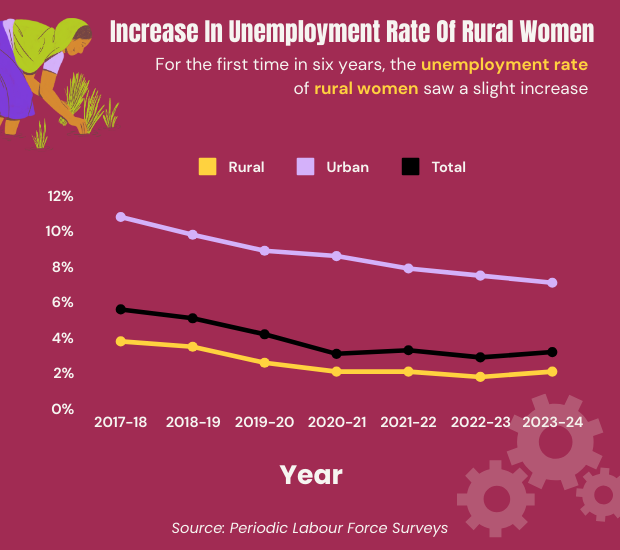

Another clear trend that emerges from the survey is that the unemployment rate for women has increased from 2.9% to 3.2%. This seemingly contradictory situation – of rising labour force participation as well as unemployment rate – can kbe explained: everyone who is working or looking for work is considered to be in the labour force, but the unemployment rate is the proportion of people in the labour force who are unemployed. This indicates that a higher percentage of women are looking for work.

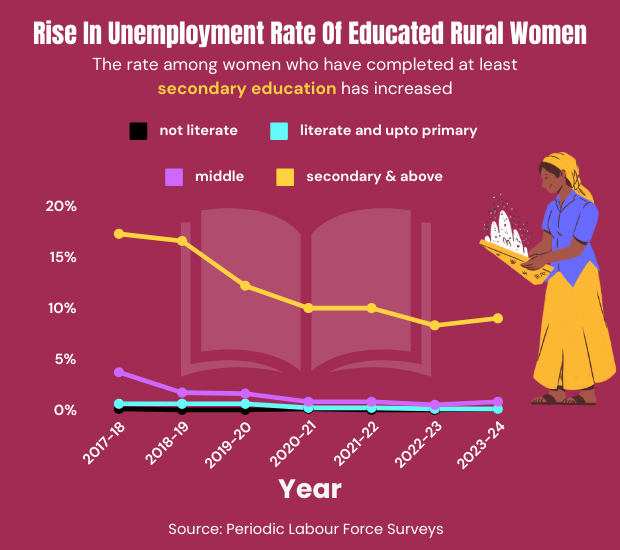

Also the increase in the unemployment rate is largely driven by educated rural women, as per the survey. Of all the groups, the rate has increased in the highest percentage points for rural women who have studied beyond secondary levels–from 8.3% to 9%. This is a possible indication of rising aspirations but inadequate opportunities for non-agricultural work.

Increasing Self-Employment

Between 2017-18 and 2023-24, the female labour force participation has seen a swift increase from 23.3% to 41.7%. While an increase has been documented in rural and urban India, the rise has been more prominent in the former, with the proportion almost doubling from 24.6% to 47.6%. And this rise is a function of increasing self-employment, as we said earlier.

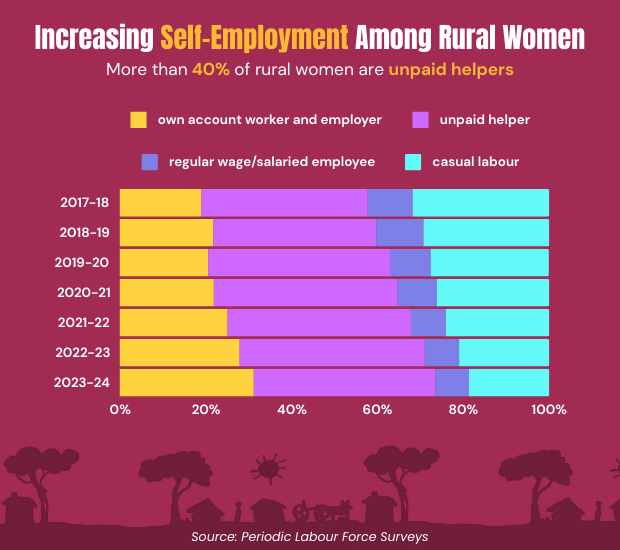

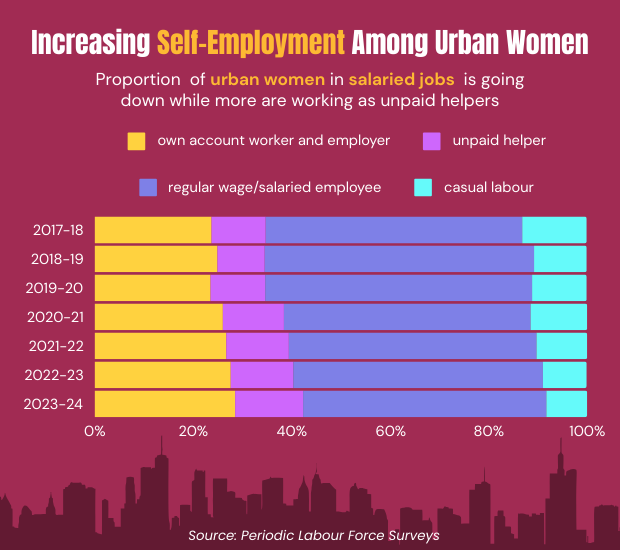

In urban and rural areas, the proportion of women engaged in salaried jobs and casual labour has decreased while self-employment has increased. In rural India, over the last six years, self-employment has increased from 57.7% to 73.5%.

Self-employment can be of two kinds – own account workers and unpaid helpers in household enterprises, who make for 42.3% of all rural working women.

“There has been an increase in the share of self-employed women which means that the kind of jobs that women are into are not of the required quality and earn very little money,” said Neetha N, professor at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies (CWDS), an autonomous research institute. “You can show increases like this but it doesn’t mean very much.”

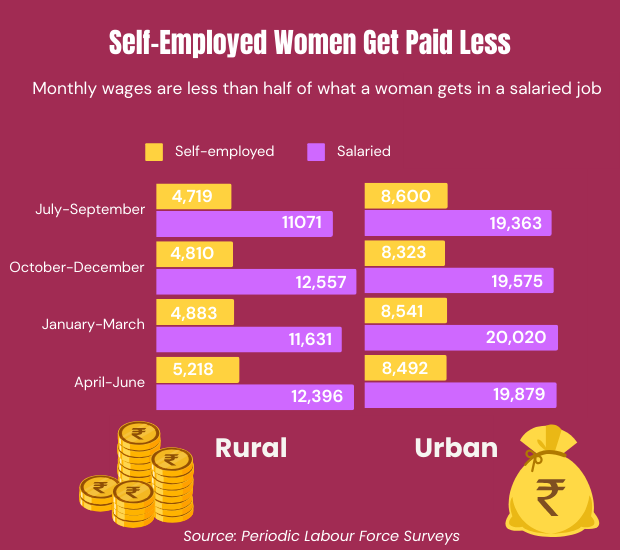

On average, a self-employed woman earned less than half of what a salaried woman earned, in both urban and rural areas. This gap was significantly narrower for men where rural men earned 25% more and urban men earned around 10% more in salaried jobs compared to self-employment.

A self-employed woman in rural India earned only around Rs 5,000 per month compared to the Rs 11-12,000 that a woman with a salaried job earned. Rural men earned around Rs 18,000 in a salaried job compared to Rs 14,000 in self-employment.

These wage trends are similar in urban areas as well.

Declining Casual Employment

The PLFS has two kinds of metrics to measure employment – usual status and current weekly status. The usual status looks at employment trends over a year preceding the survey while the latter looks at trends in the week preceding the survey.

The weekly status is a more credible indicator of the unemployment rate, said Jeemol Unni, professor of Economics at the Ahmedabad University. “Weekly status is more credible because it looks at a short period of week. Open unemployment for all the year round is normally less likely in India due to the poverty and the seasonal nature of employment,” she said in an email response.

Rural women’s unemployment rate in weekly status is much higher, at 3.9 compared to the usual status of 2.1. Similarly, the unemployment rate for urban women is also higher (8.7) in weekly status compared to usual status (7.1).

“Unemployment rate by weekly status is higher for all segments–men, women, rural and urban,” said Jeemol, adding how it could be a determinant of decreasing casual daily employment.

Since 2017-18, the proportion of rural women engaged in casual labour has decreased from almost 32% to 18.7% in 2023-24. In urban areas, this reduced from 13.1% to 8.3%.

An increasing proportion of self employment, especially unpaid help work, combined with a decreasing proportion of casual labour is a mark of an economic crisis, said Neetha. “If you have to rely on family members, who remain unpaid, to engage in any economic activity, it means that you are not getting the kind of economic returns where you can employ someone [from outside]. This is all a reflection of a larger crisis,” she explained.

Aspiration v/s Job Availability

As we mentioned earlier, there has been a notable increase in the unemployment rate for rural women, especially among women with higher education levels.

Women’s enrollment in higher education has been rising steadily for over a decade and over the last five years, more young women than men have been studying in colleges.

Between 2016-17 and 2022-23, the unemployment rate for rural women who had at least finished secondary education steadily declined from 17.3% to 8.3% and over the last year, it increased to 9%. And this increase is prominent among young rural women between the ages of 15 and 29: the unemployment rate for this group has increased from 7.4% to 8.2% over the last year.

The increase in unemployment rate among women could be a factor of aspirations, Neetha said.

“The increase [in unemployment rate] could be because the new generation of women or young girls are trying to look for possibilities beyond agricultural work. Every time we do field work, we come across a good number of young women who are waiting to join any service sector employment,” she said, adding how these opportunities mostly have very low wages and bad working conditions but there is a pride associated with them, which is driving these aspirations.

In May 2024, Behanbox had reported how young women in Haryana are ready to wait for years for a government job, an aspiration that is driven by self-respect and financial independence.

Neetha also added that the women’s unemployment rate that the PLFS shows is often an underestimation. “To define a person as unemployed, they have to say that they are available for employment and that they are searching for employment. Most women just do the work that they get and might not necessarily say that they are looking for work. So the real rates are going to be much higher,” she said.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.