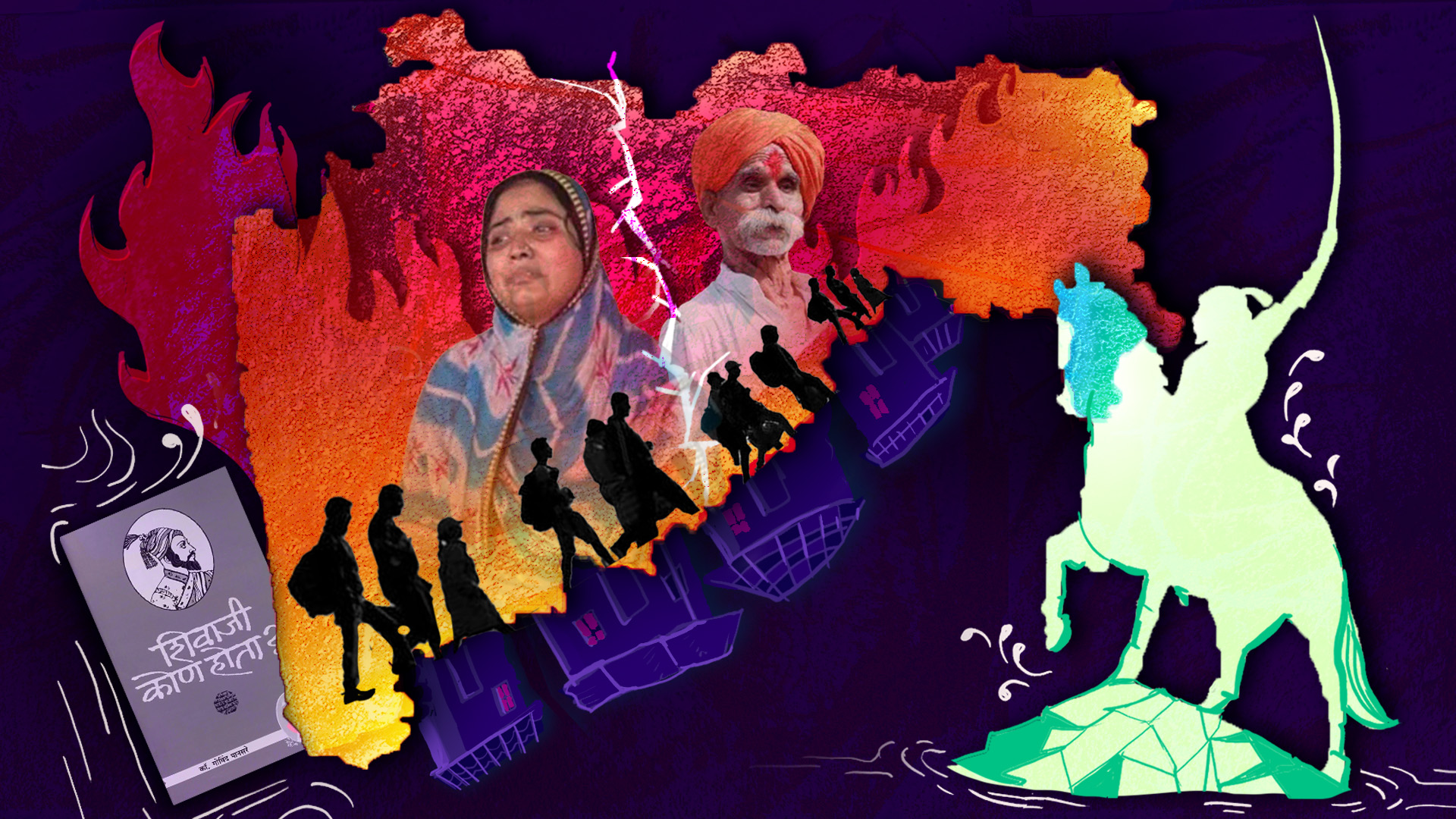

‘Land Jihad’: How Hate Campaigns Turn Vicious In Western Maharashtra

Communal polarisation is gathering pace in the state, with right wing organisations resuming campaigns around what they call land jihad. Vishalgad and its Muslim residents are among the latest victims of this hate campaign

- Priyanka Tupe

In an exceptionally heavy monsoon season, Reshma Prabhulkar, 30, was sleeping at an Anganwadi for almost a month when we met her in August. Her home was burnt to ashes in July by a violent communal mob that descended on a Muslim settlement, Musalmanwadi, in Gajapur village below the historic Vishalgad fort in Kolhapur.

She and her family, like many other victims of this violence, are yet to be provided any relief measures by the government.

Reshma, her mother Chandbibi and her sister-in-law were busy at their tiny home-based shop that sells cheap fashion accessories when a mob of right wing thugs descended from the fort into their village. They started vandalising everything and burnt down her home while hurling communal abuses at the family. The mob also destroyed everything in the settlement, from food grains to children’s toys and vehicles.

Like other Muslims, the women and children of the Prabhulkar family fled their home and escaped to a neighbouring jungle.

The Vishalgad fort has ‘illegal settlements’ around it and the Hindu right-wing groups have been agitating about this for more than a decade. The mob – made allegedly of men from outside Kolhapur – had assembled at the monument to ‘liberate’ it from the encroachments. After climbing down the fort sloganeering and waving swords and sticks, the group reached Gajapur, where around 46 Muslims families live.

‘These families of Musalmanwadi had no links with the encroachments on the fort, but they were still targetted,” said an activist in Kolhapur who did not wish to be named. We spoke to multiple civil society members, activists, and citizens of Kolhapur and they all agreed on this.

“There was heavy rain on July 15 and 16, therefore the mob could not burn down houses or vehicles, but they wrecked everything so thoroughly that it looked like it was a pre planned attack. The police too turned a blind eye to the violence ,” said the Kolhapur activist.

“‘Chalo Vishalgad’ was a call of Hindutvavadi organisations to take the law into their own hands; [they] used the encroachment dispute and vandalised 46 houses in the Musalmanwadi,” said the fact-finding report of Women’s Protest for Peace, a Kolhapur based collective that works for communal harmony and peace building. This collective emerged as a prominent voice of resistance to counter the rising tide of communal hatred in western Maharashtra. Formed in 2023, it includes women professors, activists from Kolhapur, Sangli and Satara.

The report alleged that not only the police but also a former BJP member of Parliament, and now an independent politician, Sambhaji Shahu Chhatrapti ignored the plight of the survivors. Popularly known as Sambhaji Raje, he was leading the ‘Chalo Vishalgad’ campaign.

Locals have told the fact-finding committee that Ravindra Padwal ‘Samasta Hindu Bandhav Samiti’ based in Pune remained a mute spectator to the violence. Padwal himself made videos and posted on his instagram, appealing to ‘Hindus’ to reach Vishalgad. There have been several videos showing his presence at Vishalgad.

In a two-part series, we report on how hate rhetoric and divisive communal campaigns are intensifying in western Maharashtra, an affluent sugar belt. This trend was already evident in the run-up to the Lok Sabha elections that concluded in June. And now with the state assembly elections due to be announced anytime, right wing groups are rallying again to try and polarise voters, say political and social activists.

In this, the first part of the series, we look at the aggressive and provocative strategy adopted by right-wing youth bodies to vilify Muslim communities of western Maharashtra. And how even the state does not step in to help the victims of communal violence.

In the next part, we will look at how women academics of the area are being attacked for their progressive and secular thinking.

Polls In View

It is impossible to miss the right-wing rhetoric on any platform in India, from social media to academic and cultural spaces. Provocative remarks by those in power remain unchallenged (here and here). In 2023, the year before the general elections, 668 instances of hate speech were reported, according to India Hate Lab, a Washington based research group constituted by journalists, academicians and researchers. Of these, 453 (68 %) came from BJP-ruled states, with Maharashtra heading the list (118), followed by Uttar Pradesh (109) and Haryana (48).

In Maharashtra the religious polarisation and communal violence hate campaigns intensified in 2023. , a year ahead of the Lok Sabha polls. Sakal Hindu Samaj, an umbrella body of Hindu right wing groups organised 52 “protests” focussed on what they called ‘love jihad’ and ‘land jihad’. Similar protest marches have begun in Maharashtra since August 2024. BJP MLA Nitesh Rane has been a leading face of these marches titled ‘Hindu Jan Aakrosh Morchas’ in Solapur district and Indapur taluka in Pune district. Rane has been booked for hate speech. He has appealed hindu community to boycott businesses and trade with muslims in his recent public speeches in Maharashtra.

In a way, the so-called ‘Vishalgad Mukti’ (liberation of Vishalgad) campaign is a variation on the theme of ‘land jihad’.

In the Lok Sabha elections, Maharashtra’s voters had shown their dissatisfaction with the Eknath Shinde-led Mahayuti alliance government, consisting of the BJP, Shiv Sena (Shinde faction), and the NCP (Ajit Pawar faction). Political commentators believe that these attempts at polarisation could be driven by electoral compulsions. The opposition front, the Maha Vikas Aaghadi led by Uddhav Thackeray of Shiv Sena (UBT) and and NCP (Sharad Pawar), are not aggressively countering this hate narrative though they have held some Sadbhavana rallies (peace marches) in Kolhapur.

In Monsoon, No Rehabilitation, Relief

In this atmosphere, there is little thought given to the victims of communal violence, we found in Vishalgad.

As the media and activists are prohibited from entering Gajapur and Vishalgad villages without the tehsil office’s ‘permission’, Behanbox could only briefly meet Reshma for an interview at the Gajapur police check post on August 8. “We can’t allow anyone without permission. There are strict orders from our seniors,” said a police officer on duty at the checkpost.

Dattu Kamble, a regular visitor to Gajapur from a neighbouring village, was trying to enter to get food grains from the PDS shop and get it ground at a mill. He too was denied entry by police who asked to see his Aadhaar card.

“I have not carried my Aadhaar card and phone because of the rain, just a ration card and money in my raincoat pockets. Please allow me, sir, I am dependent on this shop for the food grains. You can write down all my details but please allow me,” he pleaded with the police.

When we asked the police why civilians from adjoining villages such as Pandhare Pani, are not allowed entry to Gajapur to meet their basic needs we were told there are ‘security’ reasons.

Reshma and other women from her family also had to wait at the checkpost, on August 8, for police permission to re-enter their village after they went to meet their cousins. “The police stopped our car and made us wait for two hours at the checkpost. They won’t let our relatives visit us without their permission even though we are the victims of violence,” Reshma said, vulnerability and grief writ large on her face.

Rehana Mursal, an activist based in Kolhapur, said that her group of volunteers were allowed in with relief material only after multiple rounds of discussions with the police.

Media reports said that Kolhapur’s district collector helped the victims of Musalmanwadi violence but Reshma denies this. In the first week of August, some Dawoodi Bohra industrialists approached the state’s guardian minister Hasan Mushrif and offered to help rebuild the homes of the victims, said sources, but they were told to hold off till the rains end in September. In July, when communal violence broke out, the district, prone to floods since 2018, received approximately 320 mm rainfall.

The crisis that followed the mob violence hit the victims in several ways. Students were not able to attend school or college for a month after violence. Section 144 prohibiting the assembly of more than five people is in place even today. While the number of police personnel in the villages and at the sites of violence has decreased, their presence remains noticeable.

‘Had To Delay Burial For Fear Of Mob’

In a phone interview with us, Kausar Malda spoke of the nightmare of her father’s death in this troubled period. Najeeb Mujawar, a priest of Dargah at Vishalgad fort, died on July 14 because of hypertension, according to his family.

“Social media posts on the encroachments in Vishalgad made by youth groups had started circulating a week before the mob attack. My father started panicking when he saw this and his health deteriorated further. We admitted him to a private hospital in Kolhapur. He died three days later, and since our home and ancestral burial ground is at the Vishalgad fort, we took his dead body home at night, fearing a mob attack in the morning. Then the nightmare began.”

Kausar and her family members ran fearing for their lives even as their father’s body lay at home. The body could not be buried until evening, when the mob dispersed. The mob returned to the Mujawar home the next day, on July 16, with the administration staff responsible for demolitions and destroyed it.

“My father deserved a dignified janaza (funeral). Who gave them the right to vandalise in peak monsoon? We requested people to come for the burial, but not even four could turn up because everyone feared for their lives. Can you imagine our trauma – a loved one lying dead inside the house and a mob outside?” she asked.

The violence kept tourists off Vishalgad and this hit the small businesses – eateries and hotels – for a month. “They forced us to shut our shop for a month, and we suffered the loss of Rs 50,000,” said Divya Dhumak, owner of the Baji hotel, located at the Pawankhind entrance to Vishalgad.

Conspiracy Theories And Hate Narratives

Behanbox interviewed more than a dozen people from affected villages. Divya Dhumak recalled that a mob of Hindu right-wing youths went past their hotel waving swords and sticks and raising slogans. What saved the hotel, she said, was its apparent Hindu name ‘Baji’.

However Muslim households and shops were identified and vandalised. This is not an isolated attack on minorities in the region. Sahil Kabir, a Kolhapur-based writer and activist, has been documenting such incidents. He said: “Irshad Mulla, a young man from Rendal village of Hatkanangale taluka in Kolhapur, was detained by the NIA (National Investigation Agency) some months ago. When they took him into custody for questioning, far right Hindu villagers pelted stones at his home. Irshad was released the same day – he had been wrongly detained because he resembled another accused. But no FIR has been filed against the stone pelters and his family lives in fear.”

A fact finding report of Women’s Protest For Peace, a Kolhapur based collective of progressive women, talks about repeated instances of communal violence. “In June 2023, houses and shops of the Muslim minority community were attacked in the city of Kolhapur over a Whatsapp status. It was intended to create terror and fear in the minority community and to destroy communal harmony. The perpetrators of the incident have not yet been punished,” it said. A similar pattern of violence was observed in Satara in August 2023, where Muslim youth were implicated in cases on the basis of proxy social media posts and stories, as Behanbox reported earlier.

Muslim scholars and activists believe that these are deliberate attacks to terrify and displace the community and deprive it of land, home ownership and businesses.Sahil expressed, ‘Recently proposed amendments in the Waqf Bill will ultimately destroy the autonomy of muslims in the decision making of Madrasas and Mosques and affect their land rights.’ “It’s a communal agenda,” he says.

Sarfaraz Ahmad, a Muslim scholar from Solapur expressed concerns over communal clashes in the state. “Creating communal tensions is an agenda of electoral politics, it is a trap to keep Muslim youth engaged on religious issues so that matters of health, education, jobs do not have to be addressed,” says Ahmad pointing at upcoming assembly elections in the state.

Manufacturing Hate

The rise of right-wing hate in western Maharashtra has far-reaching consequences for the region’s social and political fabric.

Sambhaji Bhide, a prominent Hindutva leader in Western Maharashtra, particularly in the districts of Sangli, Satara, and Kolhapur, is at the centre of many of these controversies and hate narratives. He founded Shivpratishthan Hindustan, an organisation centred on the legacy of Shivaji Maharaj and his son Sambhaji Maharaj. However, it is often criticised for its provocative and confrontational style of events.

Bhide’s young followers, known as dharkaris (warriors), have faced accusations of hate-mongering and Islamophobia. These followers have been involved in the incidents we detailed earlier. Bhide himself has been a controversial figure, having been booked on multiple occasions for his derogatory remarks.

He trains youth through thematic events with titles such as ‘Gadkot Mohim’ (treks to historical forts), ‘Balidan Mas’ (a month for honouring Sambhaji Maharaj), ‘Durgamaata Daud’ (a run dedicated to Goddess Durga). He also initiates them into roles as ‘Shivbhakta’ (devotees of Shivaji Maharaj) and Dharkaris. Over the last 30 years, thousands of young men in the 14 to 30 age group have been attracted to these events, and ‘trained’ there.

During ‘Balidan Mas’ participants engage in month-long silent marches, fasting, cultural programmes, and public gatherings to celebrate Sambhaji Maharaj’s legacy. Participants forgo certain comforts to express their solidarity with his hardships during his imprisonment by Emperor Aurangzeb.

Western Maharashtra is a fertile ground for cultural observances such as the ‘Durgamaata Daud’. A large gathering of participants, including many women, run or walk as a token of worship. In recent years, the event has seen rising participation, often drawing thousands of devotees who see the daud as both a fitness and spiritual activity.

Bhide has also been stepping up the rhetoric around re-building a golden throne as a symbol of Shivaji’s valour and reign at the Raigad Fort and it has found a following among the state’s youths, particularly in the western region. He says he will do this with public contributions and the artefact, when it is built, will be protected by the youth. ‘Thousands of young men have signed a sankalp patra or oath with their blood to do so,’ we learnt from the sources.

All these events are the tool to mobilise Hindu youth and provoke them, says activists in Sangli who want us to protect his identity. One of the former followers of Bhide and Shivpratishthan Hindustan, Indrajeet Ghatage, described his experience in an interview with Marathi journalist Raja Kandalkar for Lokmudra, a magazine. Marathi journalist Dattkumar Khandagale, a former activist of Shivpratishthan, has written numerous articles and given interviews sharing his experience of Bhide’s divisive campaign.

For example, a daily chant for the group’s followers justifies violence, even killing, and disregard for legal norms. It also dehumanises those labelled as anti-nationals, referring to them as “dogs” who should be beaten or killed.

Despite these controversies, Bhide remains a prominent figure. His name has also been linked to the 2018 Bhima-Koregaon violence.

Key Factors

The religious polarisation in western Maharashtra is spurred by the narrative of Hindu victimhood.

“Hindus youth have been constantly told that there is a great risk to their religion, at the hands of non-Hindus. This victimhood and insecurity fuels hate among them. There has been a steady increase in these hateful events after the Miraj communal violence that broke out in September 2009,” said Meena Seshu, a feminist activist based in Sangli who has been an observer of the political landscape of the district for more than three decades. She also maintained that it was not till the Miraj riots that Bhide’s clout grew in the area.

Sangli has been a land of India’s freedom fighters and leaders such as Krantisinh Nana Patil, GD Bapu Lad and Vasantdada Patil have influenced the socio-political landscape of the region.

Ajit Suryavanshi, leader of the Peasants and Workers Party based in Sangli, alleges that mainstream political parties are not beyond supporting organisations like these. “These right wing organisations received patronage from leaders of ‘secular’ parties like INC and NCP(formerly united). Leaders like Jayant Patil (NCP-SP leader), Patangrao Kadam have supported Bhide and they have attended events of Shivpratishthan several times,” he said. “Organisations like Shivpratishthan Hindustan also receive financial resources from the sugar factories in western Maharashtra, from other industrialists and it also has the support of the RSS.”

The organisation is also often criticised for its division of labour along caste lines, as per a former activist of the organisation who requested anonymity. “Brahmin youth are told to concentrate on academia and Bahujan-Dalits are being brainwashed into coming on to the streets for protests and violence activities. But when these bahujan men face police cases after violence, nobody comes to help them. It is systemic, hegimonical oppression within the organisation,” said a former activist of the Shivpratishthan Hindustan who did not wish to be named.

Social activists and political analysts believe that this is the reason why extreme right wing outfits allegedly killed Govind Pansare in 2015. His Shivaji Kon Hota? questioned the deification of Shivaji Maharaj. It opted instead to define him as a ruler focussed on the welfare of the common people, and sharply aware of the implications of political economy and the caste politics. The book sold record numbers when it was released.

“For right wing organisations, the idea of Bahujans reading Shivaji Maharaj and understanding his real historic context and secular values as a human and not god is an uncomfortable one. This takes away their currency for polarisation and hate,” said Bharati Powar, a Congress leader and former corporator from Kolhapur. Powar believes that Kolhapur has been more polarised after the killing of Pansare.

“The district, well known for its progressive ethos created with a legacy of Shahu Maharaj, has become the laboratory of hate in Maharashtra which has seen communal violence for the first time in June 2023,” said Powar.

Social Media As A Tool

Followers of Bhide and other right-wing organisations have been using social media, especially Instagram actively, we found in our investigation. The harassment of women academics spiked after the communal clashes broke out in June 2023 in Kolhapur and September 2023 in Satara. Hate videos are spread on the internet before and after the incidents.

The recent communal strife reported from Vishalgad in Kolhapur is also an outcome of the hate spread through vicious Instagram reels and posts put out by Hindutvavadi activists, which includes young women. They reek of toxic masculinity. Despite this, the police have taken no action against this hateful content on social media.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.