How India’s Employee State Insurance Scheme Lets Down Low-Wage Women Workers

Long distances to medical facilities, shortage of women doctors and frustrating bureaucratic hurdles discourage women workers in the garment sector from accessing the Employees' State Insurance Scheme

- Nandita Shivakumar, Rajalakshmi RamPrakash

The Employees’ State Insurance Scheme (ESIS), one of the world’s oldest and most expansive social security and health insurance programmes for formal sector workers, is falling short of the needs of low-wage women workers, shows an ongoing research project.

Women constitute half or more of the ESIS clientele. There is also evidence that the ESIS is being used by low-wage women workers to manage chronic medical conditions that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive. But the ongoing study by non-profit Cividep India, which focused on improving healthcare systems for women garment workers in India, shows that despite the scheme’s vast reach, it does not quite serve as a model for universal health coverage.

The reasons for this that we detail later include factors such as the distances between industrial locations and ESIS medical facilities, lack of gender-sensitive services, and bureaucratic hurdles that complicate access for women workers, especially migrants. These issues force the workers to either seek out expensive private medical practitioners or settle for quacks.

The frustrating experience of Rabani, a 29-year-old garment worker in Bengaluru, illustrates some of these hurdles. After a gruelling nine-hour shift and suffering from diarrhoea, she hurried to an ESIS dispensary on July 17 this year, only to find it closed. “If the dispensary had been nearer to the bus stop, I wouldn’t have wasted time waiting for an auto and could have made it before the 7 pm closing time. That day, I ended up spending Rs 500 on a private doctor—more than my daily wage of Rs 385,” she says.

The project involved conversations with ESIS officials, public health experts, trade union leaders, and garment workers in Erode, Dindigul and Bangalore to understand the problems of accessing ESIS more effectively. These interactions also threw up long and short-term solutions that we list later.

The ESIS operates a network of healthcare facilities for beneficiaries, including hospitals, medical colleges, and diagnostic centres. Within this system, ESIS dispensaries serve as the foundation of primary health care delivery. These dispensaries function as the first point of contact for insured workers and families, providing outpatient services.

The ESI Act – which created the ESIS – was passed in 1948, even before the Constitution came into effect, reflecting the post-World War II welfarist commitment of the nascent Indian state. Today, the ESIS extends across 35 states and union territories (Lakshadweep being the sole exception), providing coverage to 1330 lakh beneficiaries – nearly 10% of India’s total population, according to the ESIC’s 2022-23 Annual Report.

The scheme, administered by the ESI Corporation (ESIC), is implemented in non-seasonal units employing at least 10 persons in factories and various service sectors, covering employees earning less than Rs 21,000 a month. The scheme offers a comprehensive package of benefits encompassing inpatient and outpatient care, preventive health services, and social security cash allowances for maternity, illness, disability, funeral expenses, and unemployment.

Surplus Funds But Services Stagnate

Contributions to the ESIS come from employers (3.25% of the employee’s wages), employees (0.75% of the employee’s wages), and state governments, without burdening the general taxpayer. The scheme has one of the lowest premium rates among insurance schemes in India, while also offering a much wider coverage than most private alternatives. In fact, the premium was even reduced because the ESIC has generated such a surplus of funds that they are unable to spend it. For example, in 2022, the ESIC was reported to have had a surplus of Rs 65,000 crore, with an annual estimated growth of around Rs 8,000-9,000 crore. This is in sharp contrast with the budgetary shortfalls plaguing other government health programmes.

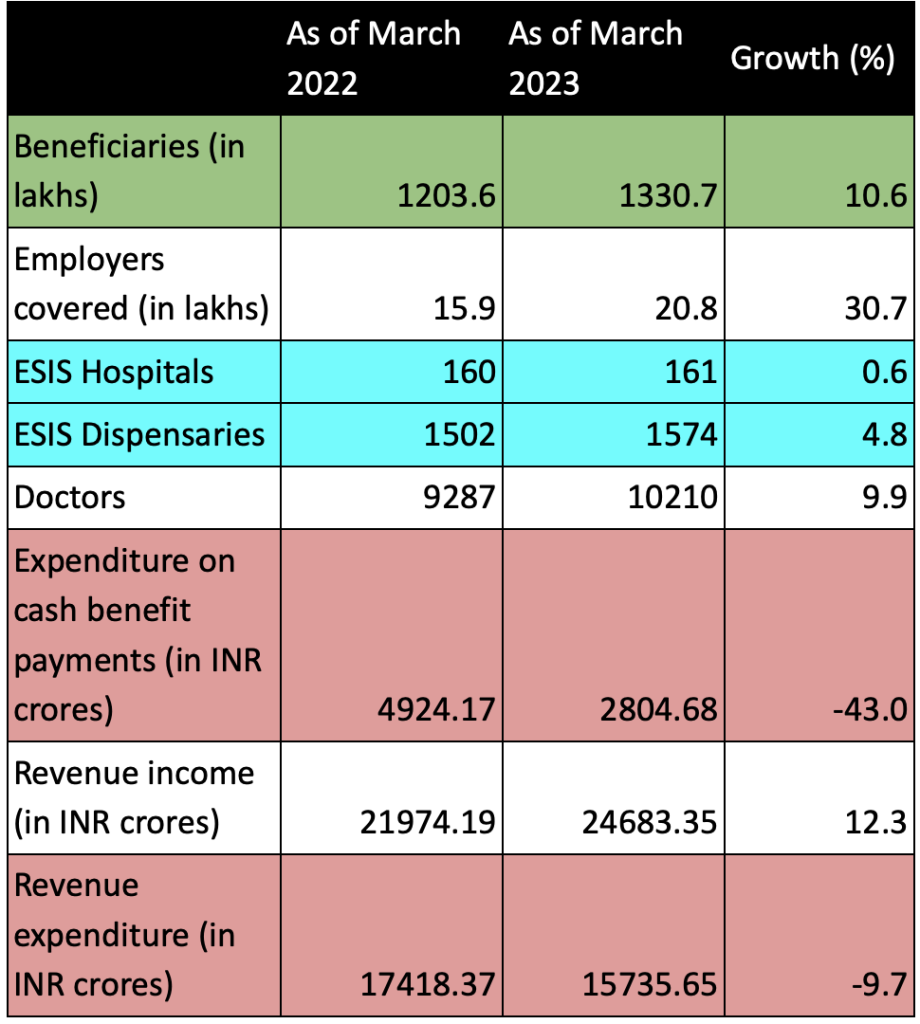

However, this financial abundance has not translated into improved services for beneficiaries. For instance, the ESIC’s latest annual report shows that while beneficiaries covered went up by over 10%, the number of medical units (dispensaries and hospitals) did not see significant change. In fact, expenditure, including on-cash benefit payments has seen a significant decline.

Numerous government audits, parliamentary committee reports, and studies have all highlighted systemic weaknesses within the scheme. This overall underperformance leaves the ESIS’s vast potential to improve healthcare of workers untapped, forcing vulnerable workers to resort to unqualified practitioners or expensive private healthcare. This undermines the very purpose of the ESIS.

Barriers Drive Women Away

When the ESIS was introduced in the 1950s, the formal workforce was predominantly male, and the system was designed for low-wage male workers. In the 1990s with a rise in the feminisation of labour, particularly in the manufacturing sector, the ESIS ensured that the scheme was adapted for the needs of women workers too. However, several access-related barriers prevent women, particularly inter-state migrants, from fully utilising its benefits.

First, there is a geographical mismatch between the ESIS medical facilities and industrial locations. Even though industries are increasingly relocating to rural areas or Special Economic Zones (SEZs), away from cities, the ESIS dispensary network has not expanded in tandem. Most women garment workers we spoke to reported that ESIS hospitals and dispensaries are often far away from their home or place of work. These facilities were also located far away from bus stops, making access difficult and expensive for low-wage women workers.

Secondly, women told us that the services often fail to address women workers’ specific needs. Thivyarakini, the state president of the Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union, pointed out a critical oversight: “ESIS dispensaries, designed to function as primary healthcare centres for low-wage workers, frequently operate without female doctors, as this is not stipulated in their policies. Moreover, these facilities are often closed between 7 PM and 10 PM, when most women return home after long factory shifts. This further constraints their access to medical care.”

This issue persists even in regions where women dominate industries, such as the garment manufacturing hubs of Erode, Tirupur, and Bengaluru.

As studies have shown, most women in these jobs regularly face issues related to sexual and reproductive health, including urinary tract infections, kidney stones, haemorrhoids, and vaginal rashes, primarily due to limited bathroom breaks, lack of nutrition, and inadequate hydration. The absence of female doctors creates a significant barrier to care for most women.

Sangeetha, a 24-year-old migrant worker from Jharkhand living in a factory-managed hostel in Bengaluru, added another layer to this problem. She explained that the verbal abuse, cat-calling, and sexual harassment many migrant women endure from local supervisors in garment factories has fostered a distrust of local men in positions of authority. These negative experiences have heightened their wariness of male doctors, regardless of their professional status.

Bureaucratic hurdles also have become an issue as these severely impede access to the benefits and reimbursements the insured women workers are entitled to. Said Yasodha PH, the general secretary of Munnade, an organisation that supports women garment workers:. “When a worker takes medical leave to visit an ESIS facility, she also has to make a separate trip to an ESIC office to claim the wage reimbursement. These offices are often located very far from the workplace as well as from the medical facility. This requires taking yet another day off work that is not reimbursed.”

This process is especially burdensome for women, who are already stretched thin, balancing work responsibilities with domestic duties, as seen in the case of Kavitha.

Kavitha, a spinning mill worker in Dindigul contracted dengue in June. The ESIS hospital granted her five days of medical leave to recover. However, when she tried to claim her wage reimbursement, she was required to visit the ESIC office in Madurai, 90 km from her home and workplace. During her first visit to the ESIC office, her claim form was rejected due to errors, and she was asked to return again. Overwhelmed by the bureaucratic process, her household responsibilities as a single mother of two young children, and the fact that the travel expenses exceeded her daily wage of Rs 392, Kavitha chose not to pursue the reimbursement.

Challenges For Migrant Women Workers

The situation is even more dire for migrant women workers who live in factory-controlled hostels. In many south Indian garment factories today, migrants constitute more than 50% of the female workforce.

In hospitals and dispensaries covered by the ESIS, migrant women encounter numerous barriers: interminable waiting times, discrimination against migrants that pushes them to the back of queues, language and cultural barriers, even prescriptions in languages they do not understand. These issues are compounded by severe restrictions on movement for those in factory-owned hostels. Their only free time – a half-day on Sundays – often coincides with ESIS dispensary closures, effectively barring access to affordable healthcare.

Seema is a 23-year-old migrant worker from Odisha in Erode. Though she has been dealing with haemorrhoids for over a week, she works nine-hour shifts as a tailor, managing with painkillers. Seema’s salary of Rs 11,000 includes the mandatory 0.75% ESIS contribution, with her employer adding 3.25%. This contribution should offer financial relief during health crises for both Seema and her family back in Odisha, including for her father’s heart condition. However, the reality is different.

When her pain became unbearable in mid-August, Seema asked to use the factory’s on-site ambulance to reach the ESIS dispensary, 20 km away. This request was denied by the factory management so she had to spend her savings on a neighbourhood quack. Her father back home also seeks private treatment, as the nearest ESIS affiliated hospital is over 70 km from their village– an impossible journey in his condition.

Like Seema, there are thousands of other inter-state migrant women workers and their families who are not able to benefit from the ESIS.

Trading Security For Convenience

The systemic issues linked to accessing ESIS facilities and benefits have had serious implications for the scheme. There has been a decline in outpatient utilisation rates, which fell from 609 per 1000 beneficiaries in 1999-2000 to just 208 by 2017-2018, according to a report by the ILO. More recent data on this rate was unavailable.

Many women are simply forgoing their rightful benefits, unable to navigate the system. Migrant garment workers in particular now actively request to opt out of the ESIS, preferring immediate wage benefits over long-term social security. This trend has even created a dilemma for HR managers, caught between workers’ preferences and legal compliance requirements.

The dissatisfaction with the ESIS has also resulted in some factories introducing private group health insurance schemes. These schemes have gained popularity among migrant workers as they offer easier access to private healthcare centres with shorter waiting times and more personalised attention. Some workers we interviewed even appreciated the improved coverage for minor ailments such as back pain, muscle strains, flu-like symptoms and others.

However, by opting for private insurance, workers forfeit crucial ESIS benefits for major health expenses, including maternity coverage, lifelong compensation for work-related disabilities, and pensions for dependents in case of occupational fatalities.

Thivyarakini called out another troubling consequence of this trade-off: “With private group insurance, companies are now able to shield themselves from scrutiny in cases of recurring accidents or serious health issues, including those stemming from gender-based violence.” Unlike the ESI Act, private insurance schemes do not mandate reporting to the government of workplace accidents and occupational diseases. This leads to a loss of crucial health data, especially with regard to occupational safety and health (OSH).

This lack of transparency is particularly problematic given the opacity around the functioning of factory-owned worker hostels, where migrant women residents often face restricted movement and limited communication. The information gap created by private insurance schemes hampers effective monitoring of industry-wide health and safety concerns, as government bodies and trade unions lose access to vital health data. This makes it also increasingly difficult for authorities to take action or identify emerging trends in OSH.

Practical Solutions

These challenges demand a multifaceted approach that addresses both systemic issues and immediate concerns.

Doctors who have treated numerous garment workers at ESIS hospitals in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, and who interacted with us on the Cividep project, emphasised the need for comprehensive change. They told us that the path forward requires more than just systemic reforms – it demands a collective acknowledgment from both governments and employers that the health of these women workers is as valuable as their labour.

They also stressed that improving preventive healthcare must begin by addressing root issues, such as the immense stress caused by high production targets, oppressive working conditions, and restrictive conditions imposed on women migrant workers in hostels.

All stakeholders consulted during the project agreed that despite its current shortcomings, the ESIS scheme still holds great potential to provide effective healthcare for workers.

Thivyarakini affirmed this view: “The ESIS’s coverage spans 566 districts and all levels of care – outpatient, inpatient, primary, secondary, and tertiary – with minimal exclusions. This makes it an invaluable resource that should be enhanced to better support all women workers. It should not be mindlessly subsumed under newer schemes like PM-JAY (Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana). But it should be made more accessible so that women are not forced to seek out-of-pocket options and go into debt.”

While the PM-JAY focuses on providing health insurance for economically vulnerable populations, ESIS offers a broader range of benefits as a comprehensive social security scheme, including unemployment support, maternity leave and outpatient care. Its sustainable funding model, supported by contributions from employees, employers, and active involvement from both state and central governments, as well as worker bodies, makes it uniquely suited to address the needs of the working population.

The initial findings of our ongoing project, highlighted six critical solutions. These proposals, born from the lived experiences of those most affected, offer a roadmap for transformative change.

Immediate Steps

- Improved Factory Management Cooperation: Developing guidelines and incentives for factory management to facilitate workers’ access to ESIS services is crucial. This includes mandating transportation to ESIS facilities when needed. There is even scope for factories to arrange regular shuttles to the nearest ESIS dispensaries/hospitals.

- Introducing Mobile Clinics: The introduction of mobile ESIS clinics could significantly improve healthcare access for women workers with restricted mobility. These clinics could regularly visit manufacturing hubs and SEZs, and even employ staff fluent in the languages spoken by migrant workers. The success of models like the Bandhu Clinic run by the Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development in partnership with the National Health Mission in Kochi, which reaches over 80,000 migrants per month, demonstrates the potential of this approach.

Systemic Solutions

- Enhancing ESIS Dispensary Accessibility: There is a critical need to make ESIS dispensaries more accessible and responsive to women’s needs. This includes strategic locations near bus stands and SEZs where many factories are situated, extended operating hours aligned with women’s schedules, and ensuring the presence of female doctors.

- Expanded Scope of Services at Dispensaries: Dispensaries should also evolve to offer a comprehensive range of services, including reproductive and sexual health care, mental health support, and occupational health screenings tailored to women’s work environments, especially in women-dominated industrial regions.

- Streamlined Claim Process: Simplifying and digitising the reimbursement process for sickness benefits is essential to reduce the need for multiple visits to ESIC offices, which is particularly burdensome for women migrant workers residing in hostels.

- Sex Disaggregated Data and Reporting: Implementing comprehensive sex-disaggregated data collection and reporting is crucial. This can help ESIS gain insights into gender-specific health trends and disease patterns.

As the female workforce continues to expand across many manufacturing industries in south India, the need for a gender-sensitive and migrant-friendly healthcare system becomes increasingly critical.

[All names of workers have been changed to protect their identity.]

This article is authored by Nandita Shivakumar and Rajalakshmi RamPrakash, both of whom are associated with Cividep India, a non-profit organisation committed to promoting workers’ rights and corporate accountability in global supply chains. For more information, visit: www.cividep.org.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.