[Readmelater]

Blockades Are Putting Lives Of Women, Children At Risk In Manipur’s Relief Camps

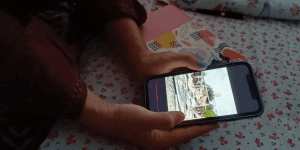

The blockades mounted by community vigilantes in Manipur make it hard for critical relief material, especially medicines, to reach relief camps. It is the women and the children who suffer the most

Lamvah Touthang gave birth to her second daughter (sleeping on the bed) in the forests. Now with a third on the way, and not enough to feed them, she’s worried how they will manage in a relief camp/ Makepeace Sithlhou

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.