Rape Survivors From Nomadic Tribes Get No State Support, Compensation Or Counselling

Stigmatised and doubted when they report sexual violence, women from NT DNT communities are never informed about the resources the state provides to rape survivors

- Priyanka Tupe

Trigger Warning: The article contains mentions of rape and sexual violence.

Sarita*, 25, a cane cutter from Jamkhed taluka in Ahmednagar, was working in a cane field in Naigaon village when her son’s teacher called that the boy had gone missing from school. Panicked, she decided to take a bus to Barshi in Solapur where the Ashramshala, a boarding school for tribal children, was located.

“I was waiting with my brother-in-law near the Bhoom bus stand. At the vadapav stall there, a constable and another man confronted us. ‘You look like thieves, come to the police station,’ he said. He demanded Rs 10,000 to spare me. I pleaded for my life and dignity. I said: ‘I am a poor daily wager, how can I arrange this much money?’” she recalls.

When the threats did not stop, Sarita called her mukadam (contractor) to transfer the bribe money to the accused over the phone. But the accused did not relent – on the pretext of taking her to the police station, he took her to the nearby fields and raped her. This was four months ago.

Sarita breaks down when she recalls her trauma. But nine days after the incident she was back at work in the cane fields. Her financial burdens had multiplied and she had no time to deal with her distress. For, she had to now not only repay the older uchal (loan) she took from the mukadam but also the Rs 10,000 he had sent to the accused. Incidentally, her son was later found near the ashramshala, having left the premises without informing his teachers.

Sarita is a Gaypardhi, a highly marginalised community that is classified as NT-DNT (nomadic and denotified tribes), and highly vulnerable to sexual violence for reasons we discuss later. On paper, there are two compensation and one rehabilitation scheme she could have benefitted from the moment she had reported the crime two days after the incident with the help of the Gramin Vikas Kendra, an Ahmednagar-based non profit that works with the NT DNT community.

She should have been informed by the investigating officer about the two state schemes run by the District Legal Services Authority – Manodhairya, which sanctions a financial assistance of up to Rs 10 lakh for the rehabilitation of survivors of sexual violence, and the Maharashtra Victim Compensation Scheme. She should also have been informed about the Bharosa counselling cell run by the police for the survivors of gender based violence.

Sarita, like several others of her community, does not have any identity papers or documents, no Aadhaar card and bank passbook that are needed to apply for the compensation. It was only after Jamkhed-based social activist Vishal Pawar of the Gramin Vikas Kendra stepped in that Sarita got an Aadhaar card in May 2024.

The investigating officer should have sent a copy of the FIR, along with the medical report and the victim’s statement and the preliminary investigation report to the District Legal Services Authority within an hour by any mode of communication including SMS and email, but this was not done either. Once this is done, an immediate aid of Rs 30,000 should have been given within the 7 days under Manodhairya scheme. None of these procedures were followed.

Sarita is yet to get any compensation.

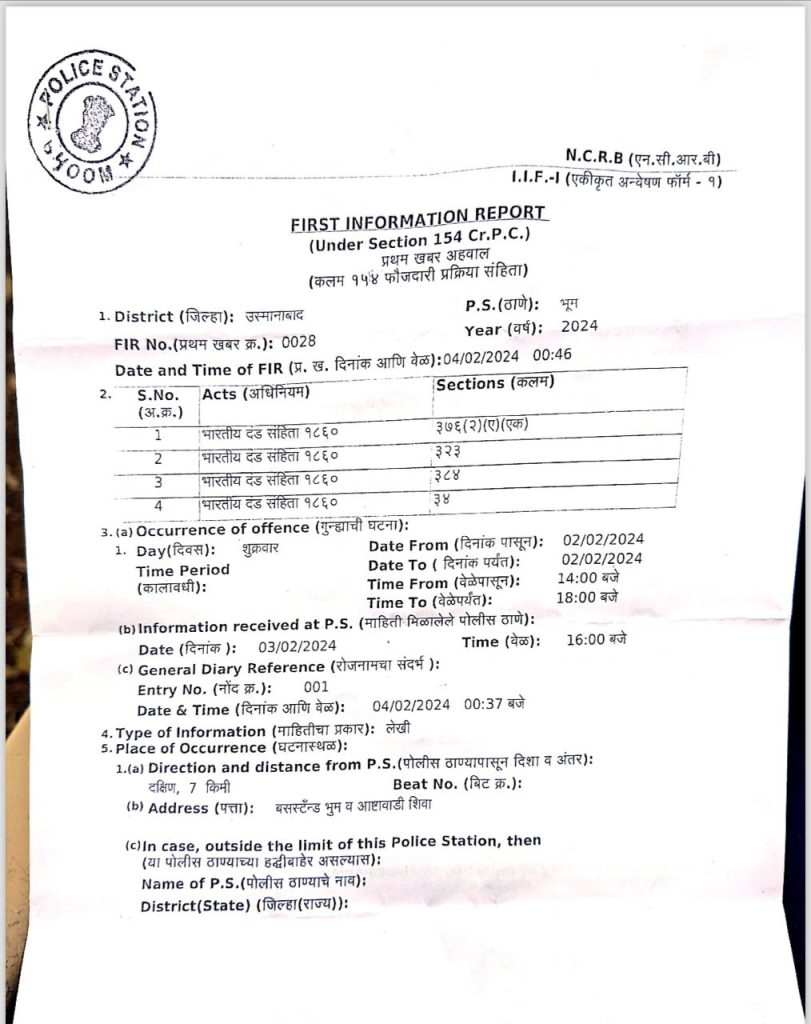

An FIR has been registered against the accused, a police personnel stationed at Bhoom police station in Dharashiv/ Osmanabad district, Dagadu Bhurake, and another civilian, Sagar Chandrakant Mane, under sections 376 ( 2) (A) (1), 323, 384, 34 of the Indian Penal Code. Both were arrested and released on bail last month by the Bombay High court Court’s Aurangabad bench though the sessions court had rejected their bail applications.

Since both the accused are from the Scheduled Tribe community, Sarita cannot seek justice under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Gaypardhi, Pardhi and Phasepardhi groups are classified as ST in Maharashtra but they can access the Act’s provisions only if the accused is from an oppressor caste.

Behanbox contacted the Bhoom police via phone calls and emails on why Sarita was not counselled on her right to various compensatory and rehabilitation schemes. We will update the article when we get a response.

There are around 5 million people belonging to NT DNT communities in Maharashtra and around 60 million in all of India as per the last census conducted in 2011, a number that would be significantly higher now. Historically labelled as ‘criminal tribes’, a stigma that is prevalent to the present day, their testimonies and complaints of crimes are hardly believed by the police. They are also not counted as a separate administrative category because of which crimes against them are not recorded in the national crimes database. All this makes it harder for them to access justice and any form of state support.

In fact, access to justice is unequal for most women and gender diverse persons from communities at the margins. In our new series “Violence,Marginality and Justice” Behanbox will report on the many structures– social, political, administrative and legal– that perpetuate gender based violence and access to justice. This is the first story in the series.

Prejudice Every Step Of The Way

As a daily wager Sarita does not have the kind of money needed to travel to a taluka like Jamkhed or bigger village, kharda, to process her documents for any scheme. It was activists and individuals who pulled funds together to help her with the many trips she had to make to the session courts of Ahmednagar. Currently Pawar is helping her with the compliance processes for the state compensation schemes.

Activists and women from the community tell us that few get justice for gender violence and this is compounded by low literacy levels. There is no official data on the number of cases of sexual violence against women from NT DNT communities in the National Crime Records Bureau.

“The historic constitutional injustice these communities have suffered is the first hurdle in the process of securing justice in cases relating to gender based violence,” says Nikita Sonawane, lawyer and co-founder of Criminal Justice and Police Brutality Project. “For Vimukta women (as Sonawane chooses to describe the group) there are no administrative categories like SC or ST. At the police station level, there is no mechanism in place to track these cases.”

The other problem is that given their historic criminalisation and resultant institutional biases, the community fears the police and administration. Activists say that despite the decriminalisation of the NT DNT community, the police and defence continue to use prejudicial statements such as ‘woman from a criminalised community’ or ‘not trustworthy’.

In several interviews with rape survivors from the NT DNT communites from Mumbai, Kalyan, Satara, and Ahmednagar, we were told that the women not screened properly by doctors at government hospitals because they are considered ‘unclean’.

“Critical biological evidence in rape cases is often destroyed because survivors fear intimidation by the police and also because they lack knowledge of the relevant laws and support systems,” says Sonawane of the Criminal Justice and Police Accountablity Project. However biological evidence is not the only conclusive evidence in rape cases, courts have ruled time and again.

“Patriarchal notions associated with family pride also prevent NT DNT women from seeking justice,” says Shaila Yadav, activist based in Satara. The men do not support women initiating legal action against those accused of gender violence because that would “malign the image and pride of the family”.

Not ‘Ideal’ Victims

Sonawane says that in her experience the police often tend to attribute malafide intentions to complaints of sexual violence by Vimukta women, alleging that they want to defame or blackmail the accused. The police then weaponises the survivor’s case against her to reinforce the “criminal” label, she adds.

“These women are not considered ‘ideal victims’ and therefore trustworthy,” she says. As legal scholar Surbhi Karwa had said in her analysis on the subject for Behanbox, women who are sexually active, drink, have multiple partners, are from marginalised social groups, or sex workers or are generally outgoing fall outside the category of ‘ideal’ Indian women and their testimonies do not get the confidence they deserve.

A teenage survivor of sexual violence from Kalyan told us that there is a deep-rooted institutional bias against women from the NT DNT groups who report harassment or rape. “I have experienced that people don’t believe us. They say: ‘Hyana kon haat lavanare (who will touch these women)?’” says Ambica* who belongs to the NT community. Vishal Pawar recalls several cases where he had to protest at police stations along with other activists to ensure the registration of an FIR in a rape case.

“For these women, police stations are places associated with trauma, beatings, and arrests. These are not secure and safe spaces for survivors, they feel. I had to go to the police station with dozens of activists even in Sarita’s case and the police tried to stop them from registering an FIR, but our collective pressure compelled them,” he says.

No Resources

Like Sarita, dozens of women we interviewed from Kalyan, Satara, Ahmednagar are not aware of the free legal aid provided for the poor and marginalised groups by the state funded District Legal Aid Services Authority. Nor are they aware of the processes to be followed at police stations and courts. Sarita, for instance, had no idea why she had to visit courts after the registration of an FIR or why she had to appear before the magistrate to record her statement under Cr.P.C. (Code of criminal procedure) section 164.

Most daily wagers lack the money to fight cases because that means frequent travel and related expenses, as we said earlier. Sarita could not have done so without crowdfunding through Whatsapp. Not only travelling and filing expenses but daily wagers miss their wages during court hearings.

The laws meant to offer special protection to them from caste based gender violence remain largely ineffective for administrative reasons. NT DNT communities such as Pardhis are officially classified as ST in Maharashtra can be protected under The Scheduled caste and Scheduled tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989 in the case of gender-based violence by oppressor castes. For this they need to produce a caste certificate at the police stations and courts but most Pardhis classified as ST lack caste certificates because of constant migration.

Not all tribes are classified as ST across India. For example, a Pardhi woman categorised as ST in Maharashtra is not necessarily categorised thus in another state. This means that justice is not available to her in all contexts and at all locations. Nathpanthi Davari Gosavi, Beldar, Beards, Kolhati, Madari, Shikalgar, Ghisadi and several other tribes are not classified as ST in Maharashtra as they are in some states.

‘Never Slept For Fear Of Assault’

“I never slept deep till I was in my early 30s because of the fear of sexual violence. Our pals (makeshift tents) don’t have the proper doors. Anyone could intrude any time and do whatever they wanted with us,” said Deepa Pawar, founder of the Anubhuti Trust, an NGO works for the community’s betterment. Pawar herself hails from the Ghisadi tribe – one of the nomadic tribes in Maharashtra.

“The NT DNT community can’t afford pucca houses because of poverty, lack of income opportunities. They lack even basic facilities like toilets. Women and young girls have to go far from their settlement to defecate in the open and in areas that are not properly lit. These conditions make them vulnerable to sexual violence,” says Deepa Pawar.

“NT DNT families are a minority in villages. Generally there are 2-3 such families and they live outside the village limits so they cannot hope for collective support. If the accused is from the dominant caste, he gets the support from majority villagers however heinous the crime. The NT DNT community also fears retaliation by powerful accused persons and being boycotted by dominant caste villagers.” said Pawar of Gramin Vikas Kendra.

Nomadic tribes engage in occupations that mostly keep them on the streets. This includes acrobatics, ritual dances and so forth that leave them vulnerable to harassment.

“Sometimes we earn nothing, then we beg to feed our children. Couple of years ago, a restaurant owner at Dadar east touched me inappropriately when I went to beg at his counter. I shouted, he said he would call 100 (the police) and accuse me of theft. I ran away. My husband was sick so he was at home. Even if he could have been with me, what could we do? Aamhi rastyavarchi manasa, aamhala kon vicharta? (we are people on the streets, nobody cares for us),” says Ashwini* from Mumbai’s Cotton Green area.

She said she also fears feeding her infant on the streets because passing men would stare at her exposed breast. “Watchmen at parks don’t allow us in because of our clothes so that was not an option. Dombari bai mhanje rastyane jata-yeta hat lavayla kunachi pan property, aani police tar aamhala ubha pan karat nahi (Dombari women are considered ‘public property’),” says Ashwini.

Shaila Yadav says this attitude of disrespect is common. “Those who perform the ritual Vaghya-Murali dance in people’s homes are perceived as the ‘wives’ of the deity Khandoba and therefore ‘available’,” she says.

Researcher Deepa Pawar shared a similar observation- “The stigma associated with their profession gives offenders a free hand to violate the dignity of these women.”

*Names changed to protect identity.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.