Sleepless On Delhi’s Streets: Homeless Women Are Battling A Brutal Heat Wave

Extreme heat during the days and the fear of harassment at night – homeless women face a relentless battle for survival and sleep

Abida, 25, has been living under the ITO flyover in central Delhi ever since her husband abandoned her and their infant daughter three years ago. It is a hard enough life but the ongoing record heat wave has made life even more unbearable for her and her child. She can neither rest nor sleep, she says.

“When would one sleep? During the day it’s so hot and then there is hot air blown in by passing vehicles,” she says. “As for the nights, I have to stay awake. As a woman on the street with a small daughter, how can I afford carefree sleep? Any passerby can harm us. Where can we go to get some sleep?”

Sushma, 22, another homeless woman who lives near Anand Vihar in east Delhi, says she tries to find a spot to rest where she will be visible to passersby. “Parks are much cooler, but there’s the constant threat of being found,” she says. “There are men who do badsaluki (behave badly). Sometimes they try to pick you up in a car, like kidnapping. I’ve seen this happening around me.”

For homeless women in Delhi, the battle for safety on the streets is now intertwined with the struggle to survive the searing heat, we found in interviews across the city’s streets and shelters.For people experiencing homelessness, the impact of extreme heat is even more severe. Without access to safe and secure shelter or other means to mitigate the intense weather, they are left extremely vulnerable. In Delhi, at least 200,000–250,000 individuals live in homelessness, including women, children, the elderly, transgender persons, persons with disabilities and other vulnerabilities.

Intense heat also worsened the factors that contribute to and normalise violence against women and girls. A study conducted by the Asian Development Bank in India, Pakistan, and Nepal from 2010 to 2018 tracked nearly 195,000 girls and women aged 15-49. It revealed that for every 1°C increase in average annual temperature, there was a more than 6.3% rise in incidents of physical and sexual violence.

India, which had the highest rate of intimate partner violence among the countries in the study, experienced the most significant increase in reported abuse. with each degree of temperature rise, there was an 8% increase in physical violence and a 7.3% increase in sexual violence.

Another study suggests that homeless women are 10 times more vulnerable than men to harassment on the streets. They face various forms of abuse, including verbal abuse and sexual harassment by the police and passersby. Male police officers often slap and physically abuse women, even as they sleep at night, and there is also violence from other men. Repeated police harassment is a common complaint among homeless women.

Sharbari, 35, originally from Bihar, cannot even remember how long she has been living under the Nizamuddin flyover. “Our children, (one of whom is a 16-year-old son) were born in Delhi only,” she says. Working as a ragpicker, she also struggles with the extreme heat. “The heat is too much. All day long, hot air blows. During the night, we are also not able to sleep.”

However, for Sharbari, the real interrupters of her sleep are not just threats from strangers, but harassment from the police. “We would rather go and sit inside the park across the road, where it is cooler at night,” she says, pointing to the small green space between the roads. “But the police won’t let us stay there. Sometimes they even hit us with sticks to wake us, and force us to leave.”

Extreme Anxiety

The women’s concerns about safety also extend to their children keeping them restless and anxious at night. “I cannot sleep at night because of my 3-year-old,” says Abida. “There have been many instances of children being kidnapped. I keep my child close to me, tied to my chest with my dupatta at night. This way, even the slightest touch alerts me.” Since her nights are spent sleepless, she sometimes nods off during the day despite the heat, she adds.

Sonia, 30, who too lives under the Nizamuddin flyover, is a new mother with an infant daughter. “My entire night is spent hand-fanning my child using a fan or a piece of cardboard so that she can sleep properly at least in this heat,” she says.

Bharati Chaturvedi, founder and director of Chintan (Environmental Research and Action Group), emphasised the mental health impact of heat on homeless women. “Because these women are also caregivers, there’s also an impact of extreme heat on their mental health. They experience extreme anxieties and worries about themselves as providers of food, care, and safety,” she says. “One should also not forget that they are already living in heavy distress and pressure, with people violating their personal space. And there’s poverty where they have to think about where the next meal is coming from.

Bharati points to the fact that homeless women are contending with equally exhausted men for the same spaces and resources.

‘I Feel Breathless’

The homeless population suffers from a range of heat-related health issues, including heatstroke, weakness, and an increase in vector-borne diseases. They also experience eye problems like itching and redness, diarrhoea, skin rashes and irritation, restlessness, difficulty in breathing, nausea, dizziness, vomiting, and dehydration. Other health concerns include elevated blood pressure, headaches, fever, coughing, cholera, frequent nosebleeds, loss of appetite, stomachaches, and various infections.

Sharbari complains of aches and pains, fatigue and nausea. Kamal Kaur, 52, who lives at the Bangla Sahib shelter in central Delhi, says the heat leaves her breathless especially during the day. “I have diabetes and am getting my medication from the shelter,” she says.

As per a 2023 study by Housing and Land Rights Network on the impact of extreme heat on the homeless population, 45.1% of individuals reported a deterioration in their existing health conditions due to heat.

“When you are poor, access to healthcare is even poorer, especially in underserved urban areas. Additionally, you are more prone to collapse with nobody to take care of you, as many homeless people are single.”

The problem with diagnosing heat-related illnesses is that it can only by ruling out other factors, says Abhiyant Tiwari, Lead, Health & Climate Resilience at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) India. “For healthy individuals, these illnesses are easier to diagnose because it’s clear they’re caused by heat exposure and exertion. The challenge arises in non-exertional cases. For example, in individuals who are elderly, pregnant, or have chronic diseases, the underlying conditions get exacerbated by heat. This represents a large portion of the heat-related burden, which the health system often fails to attribute correctly.”

Greater Risk For Women

Women face greater health risks during heat waves due to their unique physiology. A higher body fat percentage and lower water content impacts their ability to tolerate heat and stay hydrated. Hormonal fluctuations associated with menstrual cycles, pregnancy and menopause further complicate their ability to regulate body temperature. Prolonged heat exposure can also negatively affect female reproductive health, leading to menstrual irregularities and decreased fertility.

The impact of heat waves on maternal health is significant. Temperatures just above 20°C can increase the likelihood of low birth weight, preterm delivery, and stillbirth. Each 1°C rise in maternal heat exposure is associated with a 27-42% increase in the risk of miscarriage or stillbirth.

Gunita Thakur, 22, has been living in the Nizammudin family shelter for two months. Before that, she lived in a room that she rented.. Now eight months pregnant, she says she finds it hard to sleep. “Even the slightest increase in temperature causes anxiety (ghabrahat). It’s manageable as long as the fan and cooler are working, but if there’s a power cut, then it’s a huge issue.”

Pregnancy lowers a woman’s tolerance to heat as physiological changes increase metabolic demands, raising the body temperatures. These factors not only elevate the mother’s risk of life-threatening conditions such as excessive bleeding and sepsis but also pose severe risks to the foetus.

Several women we interviewed said they take several showers or pour water on themselves to stay cool. Some also reported feeling very restless and irritable. “Because of the heat, I get so aggressive that I end up hitting my own child over silly things,” says Samina.

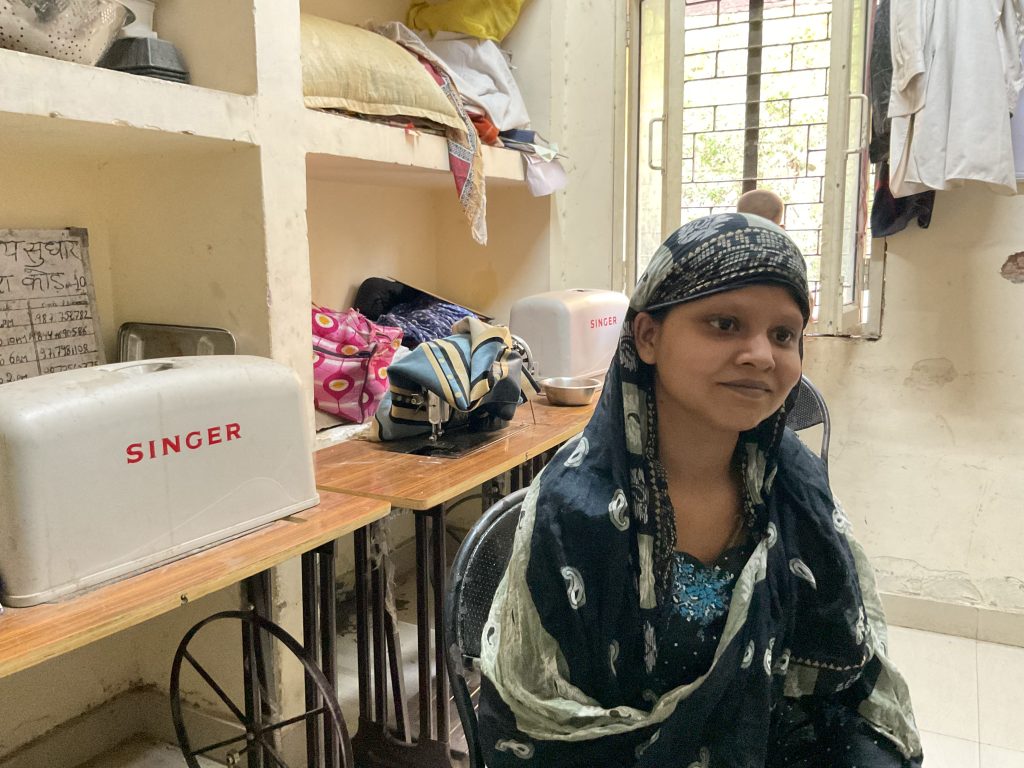

Overcrowded, Heated Shelters

Sharbari refuses to move into the crowded Nizamuddin shelter, which is just 100 metres away from where she stays. “There are so many people packed in one room, and then there’s usually commotion over who gets to sleep under the fan or in front of the cooler. If one has to sleep in the same heat as outside, why would one go to the shelter?”

Samina, 24, a resident of the shelter for almost three years, said a couple of coolers in a large space make no difference.”

Delhi has 195 shelters, including 82 permanent structures (RCC buildings) in existing government buildings, 103 porta cabins made from tin sheets, and 10 shelters constructed under a ‘special drive’. Issues such as malfunctioning coolers, fans, and irregular water supply are common here. Moreover, since most of them are tin structures, they trap heat and become highly uncomfortable. Kamal at the Bangla Sahib shelter complained that the interiors of the shelter are even hotter than the space outside.

The shelters in Delhi are managed by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB). Indu Prakash Singh, an activist and member of the State Level Shelter Monitoring Committee (SLSMC), constituted by the Supreme Court in 2018, highlighted these systemic issues as long-standing concerns. “Every year we raise the same concerns. Constant nudging is required to get things done by DUSIB,” he says.

At the Chabi Ganj shelter, a few female occupants suggested that the shelter should be on the first floor instead of the ground floor, as it currently is, for greater safety.

It’s worth noting that shelters in Delhi are highly insufficient, serving less than 10% of the homeless population in the city. Independent experts estimate that between 200,000 to 250,000 individuals are experiencing homelessness in Delhi. However, the current shelter system only accommodates 16,675 beds.

Public Infrastructure

The lack of infrastructure in public spaces also limits access to essential services. People living on the streets mostly rely on public taps and pay-per-use facilities like Sulabh toilets.

Says Samina, recalling her experience from three years ago when she lived on the streets: “Everything costs money, even using the toilet or taking a shower. Bathing costs Rs 20. If the government is charging us money for basic necessities, then why are they in power? If they have built bathrooms, why are they charging us?”

Being required to pay for public restroom use, frequently forces homeless women to use open spaces to relieve themselves, bathe less often or in exposed/covered areas, and use unclean water from public taps and leaky pipelines. The absence of a secure space for changing clothes and bathing in public areas also exposes women to gender-based violence.

According to the HLRN report, 95.1% of homeless people lack access to sufficient drinking water needed to stay cool and prevent heat strokes during the summer.

Sharbari says she gets drinking water from a nearby cremation ground. Although the water is cold, she complained that it is heavily chlorinated. “We don’t like the taste of the water, so we are always conscious of how much we consume.”

Bharati criticised the government’s approach to homelessness. “Why can’t the government just provide adequate water, coolers, and fans at shelters? They could also cover the tin shelters with cool roofing paints. Why are we not prepared when we know there’s going to be a heat crisis?”

She also suggests installation of cooling stations in public spaces such as bus stops and parks. While there are policies and programs in place to tackle homelessness and inadequate housing, they lack legal enforceability.

In 2023, Delhi implemented its own heat action plan though it failed to address the specific needs of homeless individuals.

At the heart of the issue is the skewed dynamics of the housing market. Housing policies and regulations need to factor in gender sensitivity, especially for women at a higher risk of homelessness. This includes those vulnerable to housing rights infringements such as domestic violence survivors, widows, women who head households, evictees, those from minority groups, domestic workers, and indigenous women.

(Vaishali Upadhyay, Urban Fellow, Indian Institute for Human Settlements, conducted some of the interviews for the story with the author.)

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.