No Income, Unpayable Debts: The Truth Behind PM Modi’s ‘Lakhpati Didis’

The catchy title apart, the Lakhpati Didi initiative has not really been able to increase income generation among beneficiaries

- Shreya Raman

“Today 10 crore women are involved in women self-help groups. And now my dream is to create a base of 2 crore (20 million) Lakhpati Didis in the villages”, declared Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his last Independence speech from the precincts of the Red Fort. Since then, it has been one of the most publicised missions of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party – to empower 30 million of the approximately 100 million women belonging to self help groups by increasing their annual household income to more than Rs 1 lakh, making them “Lakhpati Didis”.

The initiative is built on the backbone of Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM) launched in 2011 with the aim to improve the incomes of poor rural households by supporting women to undertake economic activities via self help groups (SHGs). But the term “Lakhpati Didi” gained prominence only after Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in 2023 that his dream was to create 20 million of them. In the interim budget, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman increased the target to 30 million.

In a recent campaign speech during the ongoing general elections, Union Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Anurag Thakur denied India’s unemployment crisis by pointing out that the government had already created 10 million “Lakhpati Didis”.

So who is a so-called “Lakhpati Didi”? This is how the government defines one: any self-help group member whose family earns more than Rs 1 lakh in a year with an average monthly income of 10,000 or more, and sustained for at least four agricultural seasons and/or four business cycles. The metric, however, does not show a woman’s income as an individual.

The main thrust of the Lakhpati Didi initiative is to enhance income generation of SHG women. To this end, it is supposed to do this by creating support, facilitating partnerships and providing training and capacity building.

To fact-check the government’s claims and to understand how SHGs are functioning, we met women who are part of these groups in Madhya Pradesh’s Khargone, Barwani and Khandwa districts, Chhattisgarh’s Baloda Bazar and Bastar districts and some parts of Andhra Pradesh. We found that not many women knew about the Lakhpati Didi initiative and that the SHGs have not been entirely successful in income generation even as it eased loan access.

The women we interviewed said that they had no state support, training or help with business planning and they were struggling to utilise the scheme’s benefits, especially access to loans. In one instance, a group of women also complained about being denied a loan.

With an increasing number of women turning up to vote and becoming an influencing bloc politically, parties have been targeting them in their campaigns. Both BJP and Congress manifestos have a list of promises relating to livelihood, basic income and reservations among others.

When Lakhpati Does Not Mean Affluence

In March 2024, Tankeshwari Kashyap, 33, from Bastar’s Usaribeda village, was told to fill a form for all the 80 women in the area who were members of SHGs. The form, which she calls the “Lakhpati Didi” form, was a survey for the annual income for the women’s households.

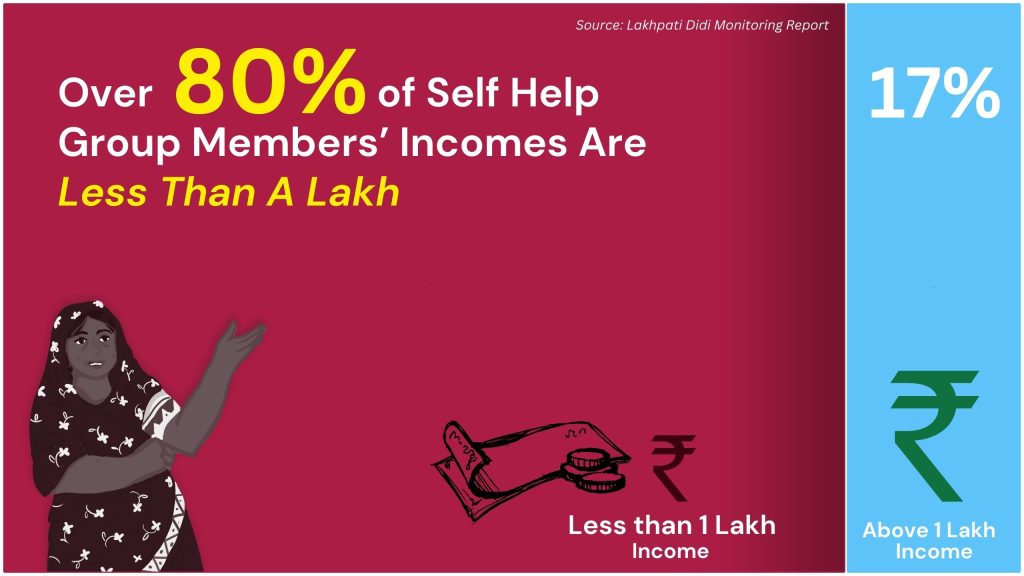

“I went to each household and asked them how much they earn from agriculture, what jobs their family members do and their earnings,” said Tankeshwari. This survey formed the basis for the Lakhpati Didi Monitoring Report released by the government. Of the 91 million women surveyed, 14 million (17%) had an annual household income of Rs 1 lakh, while more than half (52%) earned less than Rs 60,000 a year.

When Tankeshwari filled her form, she put down her family’s annual income as more than Rs 1 lakh but most of this comes from a shop that her husband runs. “I work as a Sakriya Mahila (active woman) to help support SHGs in my village and I earn Rs 1,900 per month doing that. I also work in the farm which gives us around Rs 50,000 a year. But my husband owns a shop and earns around Rs 30,000 per month which is our main income. All of this put together crosses Rs 1 lakh,” said Tankeshwari. “I did similar calculations for the remaining women in the village and filled the forms.”

This metric also does not consider the size of the household. The family of Karuna Kale, 50, an SHG member from Khargone district, earns around Rs 2 lakh per year. But her family of six are struggling to pay an 8-year-old debt and manage expenses. Talking to us for our ‘Inflation Journals’ series, she said that the family is so badly off that relatives have stopped visiting them to avoid burdening them financially. But according to government data, Karuna is classifiable as a “Lakhpati Didi”.

It is unclear whether the government has made any special budgetary allocation for this initiative as it does not find mention in the Ministry of Rural Development’s budget allocations, though the overall allocation for the National Rural Livelihoods Mission itself increased by 6.5% from around Rs 14,130 crore to Rs 15,047 crore.

Though the “Lakhpati Didi” website makes no mention of it, news articles say that under it women would receive an interest-free loan of Rs 5 lakh. The site only mentions credit guarantee for loans upto Rs 5 lakh and an interest subvention of 2% for loans up to Rs 1.5 lakh.

Also, most women we interviewed had no idea about any of these benefits or about the Lakhpati Didi initiative. Tankeshwari said she filled the form but doesn’t know what the next steps are. The only other person that Behanbox interviewed who knew about the initiative was a Bank Sakhi who lives close to the district headquarters in Barwani. Durga Patel, 45, who is a community resource person under NRLM from Hirapur, also had no idea about the initiative.

Spice Dream Goes Sour

Two years ago, 10 women from Hirapur village in southern Madhya Pradesh’s Khandwa district got together and started a self help group. Their dream was to start a mill to process and powder spices and sell them.

“A few women had come to the village and told us about the benefits of the group. So we sat down and decided to start a mill,” said Basantibai, 48. “We planned how some of us could operate the machine while others could help in packing and selling the powders. This would ensure regular income for all the women.”

None of these plans have come to fruition. “All their dreams are dead,” quipped Durga Patel.

Under the SHG scheme run by DAY-NRLM, a group that runs actively for the first six months becomes eligible to receive a revolving fund of Rs 10,000-15,000. Basantibai’s group got a Rs 20,000 revolving fund after six months. A year later, they became eligible for a bank loan but two years since they are yet to receive a loan.

“The ma’am who goes to the bank (Bank Sakhi who helps SHG members) was told to not bring any SHG loan application until the due from other groups are paid off.” She pointed out that the group is asking for a loan, not charity. “Loans that we will pay back in full. How can we do anything without even a loan?”

The Hirapur spice mill dream ended when the bank rejected the group’s loan application, not once but four times. “The bank manager told us that we would not get a loan until all other groups paid their dues”, Basantibai, a group member, told Behanox. Basantibai questions this decision. “This is not right. We are not the defaulters. We have been doing the meetings diligently and maintaining the books.”

The scheme’s guidelines state that banks should not deny loans to groups even if a family member has been a defaulter. It also states that non-wilful defaulters should not be debarred from receiving a loan.

No Business Support, Training

SHGs that secure loans from the bank struggle for other forms of business and training support to make their enterprises viable. Seven years ago, encouraged by an NRLM functionary, Suman Jadhav, 25, of Sawariyapani village in Barwani district formed a 13-member SHG along with four family members. They got a loan of Rs 90,000 sometime between demonetisation and the COVID-19 pandemic.

They also received an agarbatti (incense stick) production machine but that enterprise was a non-starter too. “We received no training. They gave us an agarbatti machine but they didn’t teach us how to use it. So it is just lying there unused,” said Suman. Training and capacity building is both a critical need as well as a stated aim of the Lakhpati Didi initiative. We, however, found training programs to be either inadequate or entirely missing.

When women receive the training, other inputs necessary for starting their business are delayed. Tankeshwari, who has been wanting to start a mushroom farm for months, got her training but has been waiting for months to collect the spawn needed to start her farm. “We will start as soon as it comes,” she said.

Sometimes opportunities exist but are not accessible. Durga said that there was a recent tailoring training program organised by NRLM but she saw no point in informing others as just the training involved travelling to Khandwa 50 km away everyday for a week. The work, after that, would require more routine travel to the city.

“The job entailed stitching cut pieces of fabric and the person had to go to the city to collect the cut pieces and then go again to return the finished product,” said Durga. “They would have provided travel costs but it is not easy to reach Khandwa from here so no one could have gone.”

In the absence of a sound income generating plan and entrepreneurial support, groups like Suman’s who have access to these loans often end up splitting the amount among themselves. “We split the amount based on everyone’s needs but we have not been able to pay it back. We do want to pay it back and get the group started again but we are struggling to survive,” she said.

Struggling To Repay

The SHGs have helped with easier and cheaper access to credit than would be otherwise available to them from other institutional sources and private money lenders, said members from Barwaha.

“Many women have been able to set up grocery stores, make papads and pickles to sell or buy buffalo to start selling milk,” said Karuna. Where women have been able to expand income generation, it has indeed been helpful in the last decade and a half.

The problem, though, is when these loans are used up for personal and non-income generating activities like Suman did or Karuna who used the loan money for her children’s education and her husband’s hospitalisation.

The struggle for Suman and her family stems from a complete lack of income opportunities. “There are no jobs in our village. We migrate to Gujarat or Maharashtra and work in gruelling conditions in the sugarcane fields to be able to survive. We won’t leave if there are jobs here but there aren’t any,” she said.

The situation is similar in Hirapur and Barwaha too. “For eight months we work as daily wage labourers and sit at home during summers,” said Basantibai. But the group is remarkable in how they support other members. “Each one of us takes Rs 100 per month from this wage earnings as savings for the group. And then we give this money to whoever needs it. That is how it has been for the last two years.”

Easy access to loans also puts the burden of repayment on the women, a pattern we observed from our reportage in Andhra Pradesh, where the state operates a DWCRA SHG scheme that offers loans at very low interest rates. Ratnamma, 38, a former SHG leader of 15 SHGs in Mangamaripeta village, a fishing hamlet in Visakhapatnam district has seen this burden first hand.

“Earlier securing credit and loans was the man’s responsibility. With these now easily accessible to women, not only has securing them become the woman’s job but also its repayment. All this has added to the burden and stress for women,” she told Behanbox.

An SHG member has to find the money every month to pay her dues else she comes under pressure from the group as well as the bank, she said. We met many women who use one of the many ways to pay their monthly instalments: borrow on interest, work out an arrangement from some members of the group or migrate from daily wage work. Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, which operate state specific SHG schemes, have the highest savings of SHGs per the National Bank of Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). Both states also rank the highest on average loan disbursement per SHG.

Back in Barwaha, Karuna and other women we met underscored the need for income generation opportunities for a scheme like the Lakhpati Didi to work. “We need more jobs that can be done from our homes,” said Salma Mansoori, who has been part of a group for 15 years.

(Bhanupriya Rao contributed to this report from Andhra Pradesh)

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.