Govt Teaching Jobs: Contractualisation Is Stifling Women’s Aspirations

Job insecurity, random transfers, non-payment of wages, and lack of benefits are hurting contractual teachers, of whom 55% are women

- Ankita Dhar Karmakar

On January 22, 2024, Assam’s Department of School Education issued a deadline to government school teachers contracted under the central Samagra Shiksha (SS) programme: the teachers had eight days to decide if they wanted to remain on contract or transition to regular positions.

The latter would have been a foregone option for Devajani Dutta, 42. She has been a school teacher on contract for 12 years at the Dakhin Tubuki primary school in the Kathiatoli block of Assam’s Nagaon district. But there was a catch – those who chose to be regularised would have to start from the bottom, earning an entry-level salary.

Assam has more than 25,000 government school teachers who have been working on a contact system since 2012. The seniormost among them would thus have 12 years of experience and salary rise.

Currently, senior primary teachers in the state’s government schools earn around Rs 40,000 on average. At entry, they earn approximately Rs 28,000, says Kulajit Thakuria, general secretary of Sadou Asom Prathamik TET Uttirno Sikshak Samaj, the union of Assam’s TETs (Teacher Eligibility Test qualified teachers) that has been demanding the regularisation of contractual government school teachers since 2015.

However, the night the state made the announcement, Devajani could not sleep. As a senior contract teacher, she earns what a regular teacher in her position does. What she misses is the safety net of social security benefits and the job security that permanent employment holds. Regular school teachers across the country get Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), medical insurance, pension, different kinds of leave, death benefits and so on. Benefits available to contractual teachers vary from state to state.

Devajani has insular glioma, a type of brain tumour that causes multiple seizures in a day, sometimes as many as half-a-dozen. Treatment requires surgery, chemotherapy and radiation and since 2017, she has spent lakhs on this, she says. Each visit to the doctor costs her around Rs 20,000-25,000. And what remains of her salary is used to pay the house rent, electricity, medicines, and food.

“I have been living in debt. I can barely afford my medicines and further visits to the doctor,” says Devajani who sometimes skimps on her medication despite warnings from her doctor. Regularisation would bring her health coverage and better savings. But then returning to an entry-level salary would be equally devastating, she says.

“If I chose the government’s option then I’d be left nowhere. The government has cheated us. This is not what we wanted,” says Devajani.

Currently, India has over 95 lakh teachers across 36 states and Union territories as per UDISE+ 21-22 report. Of them, almost 6 lakh or 11% of government teachers are on contract. Official data show that between 2017 and 2022 there was a marginal fall of 1.7% in the share of contract teachers in government schools, from 12.7% to 11%. However, states such as Assam, Chandigarh and Mizoram have seen an increase of more than 7% in the same period.

In the last 10 years, there has been a rise in the contractualisation of work, says Vimala Ramchandran, veteran scholar on girls’ education and women’s empowerment. “Not only is this deteriorating the working conditions of workers, but also compromising their dignity,” she says.

Contractualisation of work is a growing practice, wherein employers, including the government, outsource essential services to external agencies. In the case of government school teachers, this is happening in specific schemes or programmes. Contractualisation is problematic for the labour force because of the lack of social security benefits, job security, non-payment of wages, and limited negotiating power. We have reported repeatedly on how this disproportionately affects women (here, here and here.)

Most contractual teaching jobs are held by women, as we detail later. A 2023 study revealed that 55% of contractual teachers in government schools, both overall and within elementary schools are women.

How did the contractualisation of teaching jobs begin? And what is its gendered impact? We explore these questions in this story.

Transfers, Non-payment of Wages

The Congress in its election manifesto has promised to abolish the contractualisation of jobs in the government and public sector enterprises and to regularise existing contracts. The BJP manifesto makes no mention at all of the problem.

Consider the case of Delhi teacher Rita Yadav, who has not been paid her salary for the last seven months. Part of Delhi’s Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) Teachers Union, she alleges that she, along with 350 SSA teachers, have been arbitrarily transferred since October 2023 from Delhi government schools to municipal corporation schools.

Trained as a Trained Graduate Teacher (TGT) teacher, who specialises in grades 6th-10th, she is now forced to teach grades 1st to 5th in a corporation school in Arjun Nagar. “This is completely illegal,” says Yadav. Prior to her transfer, she taught 1st to 5th grades in a Sarvodaya Vidyalaya at Samalkha, Bijwasan Road, in south west Delhi.

Those transferred thus to MCD schools have not been paid their salaries for seven months, says Yadav. Across India, non-payment of and delay in wages is a recurrent trend as reported here, here and here.

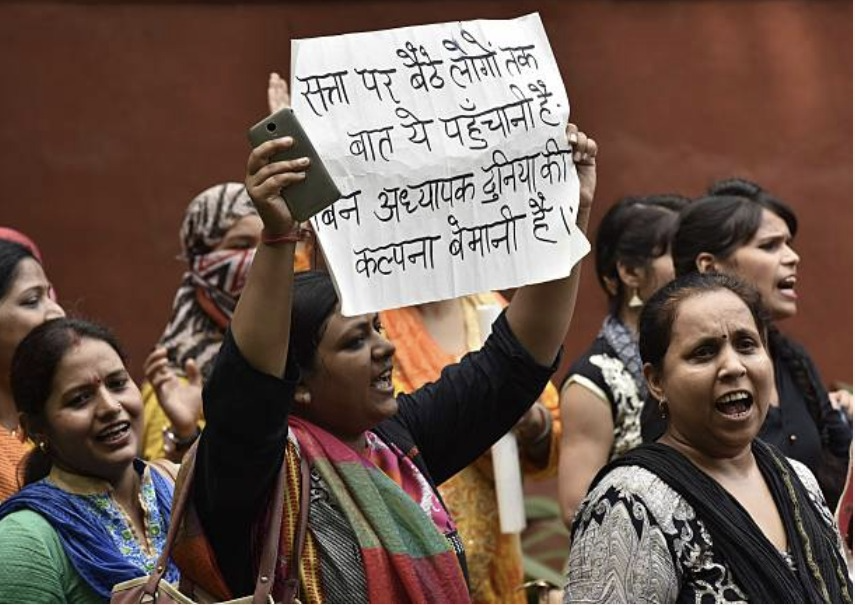

In Delhi, Assam and across other parts of India too, contractual government school teachers from time to time hit the streets to demand regularisation of their work, social security benefits, protest arbitrary transfers, and delayed payment of wages.

As of December 2023, in nine states and Union Territories, between 25% and 69% of government school teachers work on contract. Here are some numbers – Meghalaya (69%), Arunachal Pradesh (53%), Mizoram (37%), Assam (24%), Jharkhand (54%), Uttar Pradesh (25%), and the Union Territories of Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman (47%) and Chandigarh (35%), Andaman and Nicobar islands (14%).

However, teacher vacancies persist: the Ministry of Education data indicate that as of December 2023, primary schools in India have 72 lakh vacancies, and secondary schools 12 lakh, a slight improvement over figures reported in March last year.

In the last ten years, government spending on education has increased in school education, except for a reduction in 2015-2016 and 2021-22. But its share of the overall budget estimate has reduced by 50%. Despite this, why do 11% of government school teachers continue to be contractual? To understand this, we have to go back in time.

How Contractualisation Began

The large-scale appointment of teachers on contractual basis started in the 1980s when, with the aim to achieve universal elementary education, India framed the National Policy on Education (NPE) 1986. It called for the opening of new schools and the development of non-formal education. Regular teachers were appointed by state governments for all the new schools that opened up.

But in remote areas of states such as Rajasthan, there was high absenteeism, and a shortage of teachers, says Vimala. This is when the the Rajasthan government started its Shiksha Karmi Project, a primary education project initiated as a collaborative venture between the government and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) where local para-teachers were appointed on a contractual basis to solve teacher absenteeism, poor enrollment and high-dropout rates.

Soon other states followed suit. “Now under the SS, (which has subsumed the erstwhile Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), the Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) and Teacher Education (TE), the hiring of teachers on contract is an accepted practice,” says Vimala.

Data from the Public Enterprises Survey reveals that in central public sector enterprises, where more than 50% of the equity is held by the central government, between 2012-2021 more and more workers have become contractual. In March 2013, of the total 1.7 lakh employees, 17% were on contract while 2.5% were employed as casual/daily workers.

‘Permanent Cadre Is Preferrable’

The hiring of contract teachers contradicts the provisions of the Model RTE Rules which emphasises the importance of a professional and permanent cadre of teachers, says Arvind Rana, president of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan Teachers’ Welfare Association.

Further, section 18 (3) of the Act states that the scales of pay and allowances, medical facilities, pension, gratuity, provident fund, and other prescribed benefits of teachers, shall be that of regular teachers, and at par for similar work and experience. “The violation started from here,” says Rana.

The salaries of contract and regular teachers differ from state to state. In some like Assam, contract teachers are paid at par with regular teachers. However, in Delhi, salaries of contractual primary school teachers is Rs 34,800 while that of regular teachers for the same level is over twice – Rs 75,000-80,000, says Yadav.

The 2019 draft of the National Education Policy (NEP) stated the intention to end the use of contract teachers. However, the 2020 NEP does not.

In 2014, the Rajasthan High Court asked the state to stop hiring teachers on a contractual basis. Since then Rajasthan has done away with the contract teacher regime, and moves to restart this practice has been faced with stiff opposition from teachers’ groups. Other states like Manipur and Sikkim have been systematically regularising their contractual teacher cadre by introducing a contract period of two years and four years respectively – before they are regularised.

Dwindling Motivation

Devajani, a single woman, lives in a rented accommodation in Kathiatoli. She says she desperately wants a transfer to her hometown in Sivasagar, 244 km away. Despite meeting the eligibility criteria of the Assam Teacher Transfer Act 2020 with 12 years of service, Devajani’s transfer request has been repeatedly denied. She says this has worsened her health issues, especially hypertension and stress.

Rita, who was transferred twice in a month, to different schools in South Delhi says that in her experience she has seen regular teachers, especially those with “leverage”, manage postings in well-connected schools. Others like her believe that teachers on contract tend to be posted to the most disadvantaged areas and in high-poverty schools (poorly resourced schools in areas that are disadvantaged or very poor).

Rita says she was passionate about being a teacher back in 2011, but with a delay in her wages, she finds no motivation to work. The transfer has been hard – a resident of Gurgaon, earlier she could reach the school within 15 minutes now she has to undertake a 2.5 hour drive to reach her school. She is stressed about how she will pick up her two children from school on time and has to rely on her neighbours to keep an eye on them till she returns home.

There is familial pressure to leave the job, especially since her husband earns well as a Navy personnel, she says. But she draws her sense of identity from her work, she argues. “Lekin mera sarkari naukri se vishwas uth gaya hai (but my hopes from a government job are dashed),” she adds.

Studies have established that the contract system has damaged the teaching profession and impacted their social standing.

‘We Have No Future’

Manoshi Borah*, 35, a government school teacher, who works at the Longsowal Saiding LP School in Hapjan block of Tinsukia, says she considers herself lucky to be an educator. Borah has been a teacher in this school since 2012 and lives on rent near the school. Her husband is unemployed, and she has a 10-year-old son, making her the sole breadwinner of her family.

Manoshi says that when she was first appointed as a contractual teacher, she was assured that she would eventually be regularised. But that did not happen. Even after 12 years in service, she says, she does not have enough money to invest in a home or piece of land.

“Once I turn 60, I don’t know what will happen. We have no savings. We have no future,” says Borah who feels her passion for teaching diminish by the day. She also worries about what would happen to her husband and child if she is not around to support them. “Usually the families of deceased government employees receive some money as death benefit. Because we are contract teachers, we are entitled to no such benefit,” says Manoshi.

Manoshi fears are grounded in reality. She says she has seen several of her colleagues pass away leaving their families destitute. “We teachers from across Assam through WhatsApp groups pool in money to help them out. In these past years, we have raised at least Rs 10 lakhs to help 10-15 families,” says Manoshi.

No Funds, Says Govt

To achieve universal elementary education, the Kothari Commission (1966) recommended that India should invest 6% of its income in education. But between 2014 and 2024, the Union government allocated an average of only 0.44% of the annual GDP to education each year. (India’s current budgetary allocation under the interim budget is 0.36% of the GDP). This, despite the BJP government’s promise in its 2014 manifesto to increase spending on education to 6% of the gross domestic product. The amount of money allocated to the Samagra Shiksha programme has gone up by 12% compared to what was planned for 2023-24, and it makes up over half of the total education budget. However, the increase in funding for this programme since 2019-20 has been quite small, only around 3%.

Government officials when confronted about the non-payment of wages, say that they have no funds, says Rita. “Governments always use the fiscal deficit argument. But it’s a bogus argument. If you can cancel the debt of industrialists, you can also pay your teachers,” says Vimala.

55% Of Contract Teachers Are Women

Studies indicate that there is a notable trend of feminisation within the teaching profession. Women make 55% of the workforce while men make 45% of the staff in government and government-aided schools.

This mirrors the percentage of women contract teachers that stands at 55%, as we mentioned earlier. However, in government-aided schools, the gap is ever wider: women at 59% and men at 41%.

Part of the reason behind this might be because state governments have put in place policies for the recruitment of teachers which includes reservation benchmarks of up to 50% for female teachers . Data from 2017-18 show that at least 22 states and union territories did not meet this reservation norm, with the percentage of female teachers ranging from 48% to 30%.

States with high numbers of female contract teachers include Chandigarh (81%), Delhi (74%), Goa (81%), Kerala (79%), Puducherry (75%), Punjab (75%), and Tamil Nadu (75%). Of them, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh have a notably high percentage of female teachers at the primary level. As per studies, the highest proportion of contract teachers are in primary schools and in rural schools.

This is true for women teachers across regular and contractual cadre. Across school levels, government data from 2021-2022 shows that women outnumber men at the primary school level, while at the secondary level, it is men who outnumber women.

“Gender has a big role to play in this,” notes Vimala. “Not only do secondary schools have fewer contractual teachers, they have more men as they are more interested in regular government jobs.” Teachers in secondary schools are also paid much more, at Rs 65,000-70,000 per month.

Additionally, the status of contract teachers in primary schools is notably low, as they often undertake duties and classes regular teachers avoid, says Vimala. Not only this, secondary school teachers can get promoted and become District Education Officers. This is not true for primary school teachers.

Similarly, in aided schools, 59% of contractual teachers are female, with the percentage rising to 80% specifically within aided elementary schools. And in tribal welfare schools, contractual teaching positions exhibit a higher proportion of women, accounting for 41-42%.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.