How Evictions And Resettlement Upend Women’s Working Lives

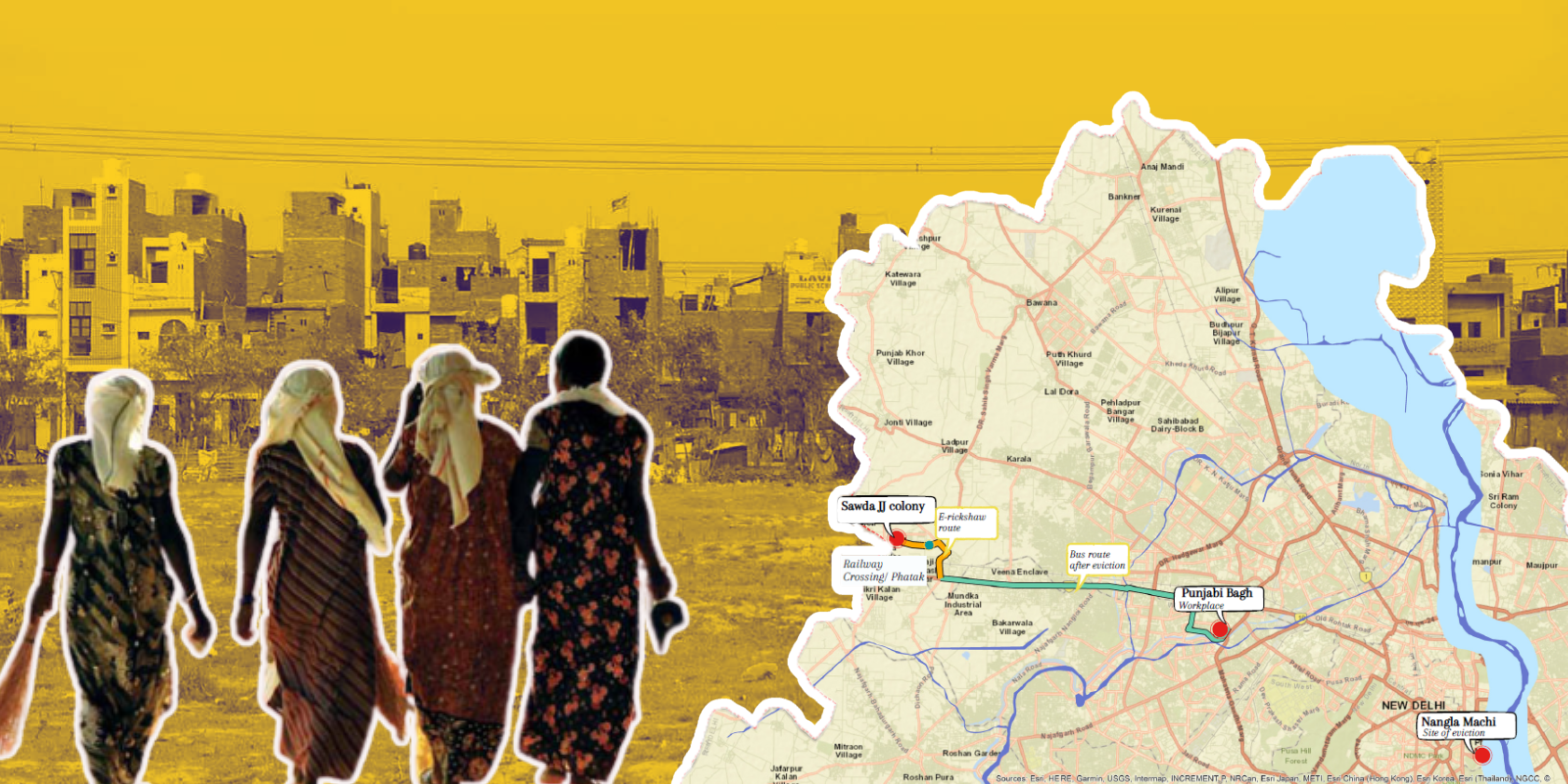

In Delhi, evictions get you resettlement housing but in areas with little access to job, services or essential facilities. And it is the women who struggle the most with travel and livelihood options

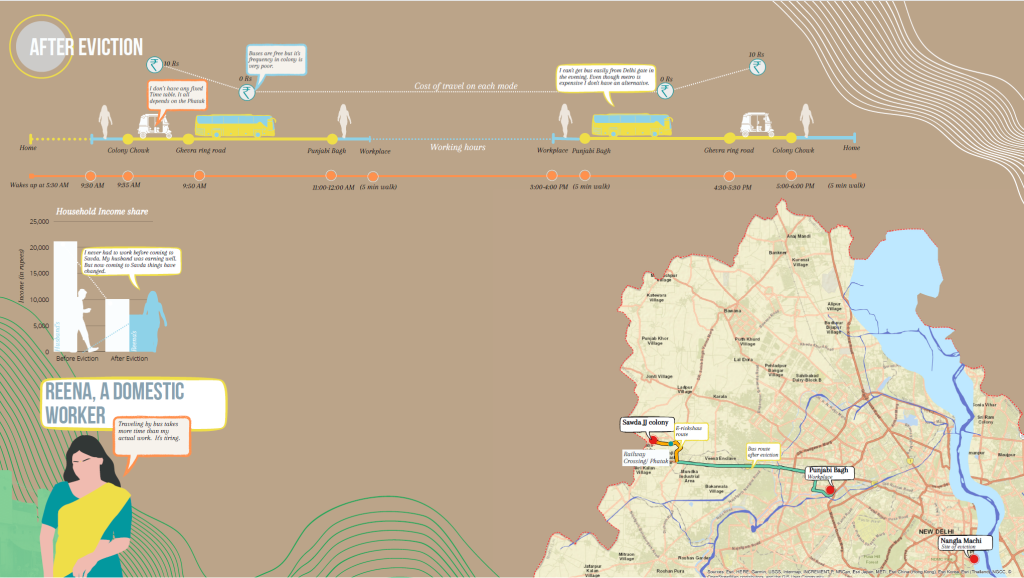

Reena, aged 45, leaves her home every day at 9:30 am, embarking on a journey of 2-2.30 hours to reach her workplace. A domestic worker in west Delhi’s Punjabi Bagh area, she lives in Savda Ghevra, a resettlement colony in the city’s northwest, with her husband and three children.

“Reaching work is a struggle, and the nearest place where I can find employment is Punjabi Bagh. What opportunities exist to earn a decent living in the outskirts of the city?” she asks.

Her jhuggi was among the 12,000-15,000 households uprooted in 2006 when Nagla Machi disappeared from Delhi’s map. Situated between the Yamuna river and Mahatma Gandhi Marg, it was a thriving settlement almost into central Delhi with many work opportunities. Only 1145 residents were provided resettlement in Savda Ghevra and Reena was amongst them.

Reena’s new home stands about 35 km from her earlier basti. “Moving to Savda felt like having to start my life anew. There was nothing here to call home when we first arrived,” she recalls. “Bekar, bilkul bekar (useless, absolutely useless),” she says.

Savda Ghevra came into existence only in 2006 after multiple eviction drives in Delhi meant to make it ‘slum free’ and ‘world class’ in view of the Commonwealth Games that was to be held four years later. It now has more than 10,000 families spread across 250- acres and relocated from over 28 locations in Delhi. Nagla Machi, Laxmi Nagar, Yamuna Pushta, Raghubir Nagar, Nangal Dewat, Nizammudin Bawri, Khan Market and Harishchandra Mathur Lane were some of the locations from which people were relocated.

Evictions are commonly carried out across urban India for various reasons. Last year, over 278,796 (2.8 Lakh People) Delhi residents were displaced for ‘urban beautification’ , ‘environmental conservation’ and ‘slum clearance’ initiatives in Delhi. With the number almost 738,438 (7.4 lakh) people evicted across the country.

What Official Policy Says

Until 1990, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) bore the responsibility of providing resettlement in the capital city. However, in 2010, the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board Act was enacted, leading to the establishment of the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) which holds the mandate for resettlement and upgrading of settlements within the city.

While the DUSIB’s 2015 policy states that “DUSIB shall provide alternative accommodation to those living in JJ Bastis, either on the same land or in the vicinity within a radius of 5 Km”, it still left in a clause for more distant resettlement: “In exceptional circumstances, it [the resettlement colony] can be even beyond 5 Km with prior approval of the Board.” These exceptional circumstances are not outlined in the current policy either.

As per a 2014 study of these evictions by the Housing and Land Rights Networks (HLRN), an organisation focussed on promoting and protecting housing, the authorities did not provide those displaced with adequate information about the proposed eviction. They also did not engage in the official process of public consultation about the eviction, the use of the land on which they lived, or the resettlement process.

According to the first residents at Savda Ghevra, their new colony was barren land covered with dried remains of a mustard field, totally devoid of homes or infrastructure such as roads, water, electricity, and sanitation.

As per UN, resettling communities should adhere to proper policies, ensuring that people are not relocated to distant areas without due process, and even then under exceptional circumstances. Additionally, as per General Comment 4 issued by the United Nations (UN) Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), several criteria need to be fulfilled for specific types of shelter to qualify as ‘adequate housing’, with secure, legal tenure, essential services, affordability, access to jobs, education and health.

In the case of Savda Ghevra, almost none of these criteria were fulfilled. Upto 30% of the women respondents claimed to have lost their work as a result of relocation, according to the HLRN study. Of the working women, 56% were domestic workers and had to leave their jobs because the site was situated very far from their workplaces. Those who chose to continue with their former employment, have to commute a distance of about 50–70 kilometres daily, and therefore leave for work by as early as 5 a.m. every day.

Women And Resettlement

Resettlement to distant areas carries consequences for all, but its impact on women is particularly profound due to their already restricted mobility and choices. A 2019 study conducted by IIT Delhi concluded that 53% of females in urban India refrain from leaving their homes, compared to just 14% males.

Women, often burdened with caregiving and unpaid domestic duties, tend to avoid long and unsafe commutes, and this includes those who are keen to remain employed. Sudha from Savda for instance, said the question of taking on a long commute to the city hit her harder than her husband.

“Eviction and resettlement have pushed people into cycles of poverty, compelling them to not only build new housing but also to invent new livelihoods and social structures,” said Veena Bhardwaj, a programme manager in SEWA, a grassroot organization working for women in Informal settlements. “In resettlement colonies like Savda, where job opportunities are scarce, residents endure longer commutes to work. This added strain exacerbates the already heavy burden on women, who must juggle caregiving duties alongside their professional responsibilities.” The stress and anxiety stemming from this also affects women’s health, she pointed out.

Reena got a plot of mere 12 sq. meters after depositing Rs 7000 later on which she incrementally built a dwelling. “First, we made a tarpaulin hut, then gradually added mud, as money kept coming, we built a solid house here,” Reena says.

But Savda offered nothing much, other than a patch of land with no amenities, or possibility of jobs. Reena’s husband who ran a water counter at the Patiala Court in central Delhi used to earn Rs 700-800 a day but he lost this livelihood source after they moved and he had to take on construction work. This reduced income forced Reena, who never worked before, into the job market.

Initially, Reena took on daily wage work but it was not regular enough. She started working in a company near the Tikri border but its inflexible hours did not leave her any time to care for her children who were young then.

It was Reena’s niece who found her a job as a domestic worker in Punjabi Bagh. Her current job provides her flexibility and 4-5 holidays a month and she earns Rs 7000 a month, up from the Rs 4000 she started with four years ago.

But Reena now pays for this flexibility and stability at work by a long commute.

Unending Cycle Of Work

Reena’s daily journey as she heads towards the colony’s chowk to catch an e-rickshaw bound for Ghevra ring road, a journey of 20 to 35 minutes depending on the position of the railway crossing on the way. But she is often held up at the crossing. This can further lengthen her wait for a bus, which arrives every 30 minutes or so. The bus journey itself could take between an hour or two depending on the route and traffic conditions. She typically reaches Punjabi Bagh sometime between 11am and 12 noon.

There is no avoiding this commute, Reena says, because wages for domestic work in her neighbouring Ghevra village is too low for the effort involved.

All this means Reena has to rise at 5:30 am to cook for her husband and children, who need to leave home by 7 am. There are other chores to finish before she leaves: cleaning, laundry, dishwashing, and ensuring water for the day ahead. There is no way she can take on another house for work “Being able to care for my home and children well is enough,” she asserts. But if her commute was shorter, she adds, she would have taken on more work.

Even if she had needed to work in Nagla Machi, she could have easily found opportunities in neighbouring areas such as Ashram, Rani Bagh, and Lajpat Nagar, she adds.

In the Punjabi Bagh home, she is tasked with cleaning, dusting, dishwashing, and chopping vegetables, a labour-intensive routine that consumes 3-4 hours of her day. Depending on her workload and arrival time, she leaves sometime between 2pm and 3pm. Reena then boards a bus back to her colony from Punjabi Bagh, followed by an E-rickshaw ride, costing her a modest sum of Rs 10 each way. It is 4pm or 5 pm when she reaches home, and is in no position to deal with any emergencies at home.

The bus schedule is unreliable but thanks to the free bus ride scheme introduced by the Aam Aadmi Party government in 2019, she now travels at no cost, a significant relief because she earlier paid Rs 15 for a regular bus or Rs 25 for an AC bus. In all, this cost her Rs 1500 a month. She has the option to use the metro but is put off by the high fares.”If the metro were free, why wouldn’t I use it?” she asks wistfully.

Her long commute leaves Reena more exhausted than her work.

Left Without Choices

Zora who lives in Savda too was already employed at a tailor’s shop in Jama Masjid’s Kabootar market before she and her family relocated. But she still found it hard to find a job in her new colony. “Why would those who come here in distress spend to get clothes stitched when they don’t even have basic shelter?” she asks.

After months of a fruitless job search, Zora resolved to return to her former employer and persist with her trade of stitching burqas and blouses. She has worked here for 25 years. The passing of her husband a few months prior to their relocation heightened her urgency to secure employment.

Zora’s earlier short commute (from Pragati Maidan to Jama Masjid) of 6 km cost just Rs 5, with buses available every few minutes. In Savda, she has to wake up by 5 am and on a 7 am bus that drops her at Delhi Gate’s Delight cinema and from there she has to take another bus to the Jama Masjid metro station. This entire trip will cost her Rs 15 and Rs 10 respectively. From Jama Masjid, the tailoring shop is just a 5-minute commute. Early morning traffic allows her to reach work by 8:50 am or 9:00am, taking a total travel time of around 2 hours.

Zora, often arriving home late, works until around 8-8:15 PM before embarking on her metro commute from Jama Masjid to Ghevra. Negotiating the railway crossing at Savda colony and Ghevra ring road, she faces sporadic delays due to passing trains. Typically, she arrives home by around 9:40 PM.

With the introduction of the metro in June 2018, Zora’s evening commute was transformed. Despite the higher cost, she finds the metro more reliable than the earlier bus rides from Delhi gate, which often left her waiting for hours. Previously, she would reach home as late as 11 or 12 at night, depriving her of adequate rest before her early morning work routine.

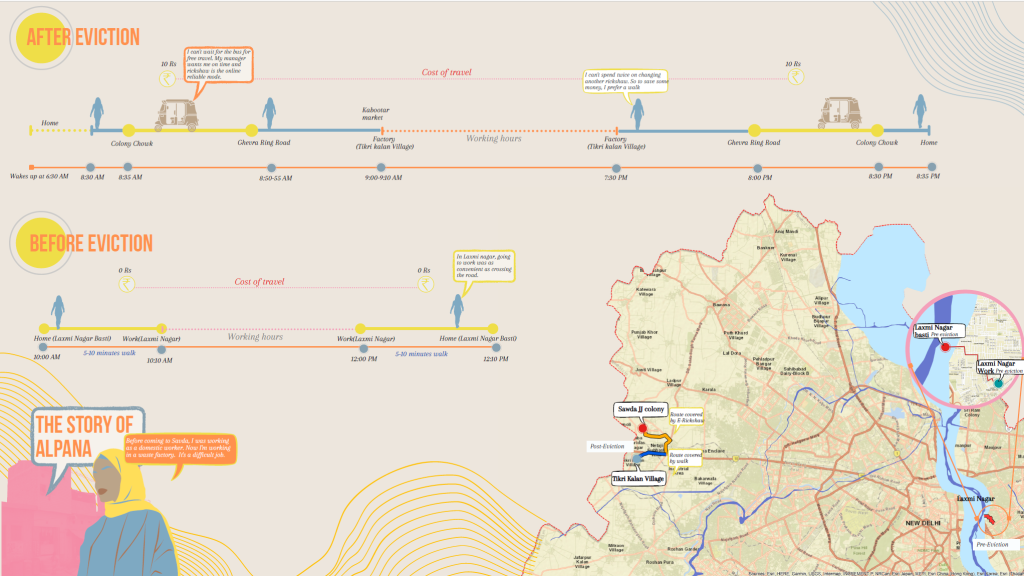

While Zora and Reena bear the burden of extensive travel, Alpana chooses to work closer to the colony. Before relocating to Savda, Alpana worked as a domestic worker in Laxmi Nagar, conveniently located near her basti.

Upon settling in Savda, Alpana faced unemployment as commuting to Laxmi Nagar daily was not feasible. Eventually, she seized an opportunity to work in a plywood factory near the colony. However, after two years of employment, the factory closed down, once again leaving her without a job. The new location of the factory is far, and commuting there daily is costly, posing further challenges for Alpana.

Alpana’s pursuit of stable employment led her to explore opportunities shared by her neighbours and relatives in the colony. Encouraged by a neighbour’s employment in a waste factory in Tikri Kalan, she decided to give it a try. She works there six days a week for a monthly wage of Rs 7000.

“There, I have to do everything, whatever the manager says,” she says. This includes tasks like separating plastics, peels, and iron, and sometimes unloading waste trucks.

Her earlier commute needed her to just cross the road to the home where she was engaged as a domestic worker. Now the journey is unpredictable and long and at the end of the day when she finishes her chores she feels exhausted. It is particularly hard in scorching summer months.

Alpana’s situation is compounded by the fact that she has four children, one of whom, her eldest daughter, works in Laxmi Nagar. Recognising the challenges of commuting daily, her daughter opts to stay in the employer’s home, visiting her own family only occasionally.

Savda Ghevra presents a case of what some scholars have called a “planned slum”: even Reena, Zora or Alpana are shifted out of their “slums”, they continue to live without access to government services or even the rest of the city. It exemplifies a mode of resettlement in which the state has in effect designated an unserviced zone for specific populations on the periphery of the city.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.