Why Maharashtra’s Anganwadi Workers Stir Is Spiralling Into A Livelihood Crisis

Faced with termination and loss of salary, striking Anganwadi workers in the state are living in fear and anxiety

- Priyanka Tupe

On December 7, dressed in the pink saree that is the uniform of Anganwadi workers, Rohini Harale, 60, got ready to leave her home in Parbhani district’s Gangakhed village. She was going to join a local protest meeting of Anganwadi workers demanding better work conditions, wages and benefits.

Harale had just sat down for a quick lunch when she complained of chest pain and collapsed. She was rushed to the sub-district hospital 46 km away where she died.

For nearly 30 years, Harale had single-handedly run an Anganwadi centre in Gangakhed’s Gautam Nagar area. At least 80-85 children benefited from her work every year. She also worked part-time as a domestic worker to make ends meet. Harale lived alone in a rented single room, she had been abandoned by her husband and had lost her parents as a child.

Two other striking Anganwadi workers died during the month-long protests being held across Maharashtra, as we detail later. Trade union leaders and labour activists have alleged that the intense work pressure borne by Anganwadi for years, compounded by the forceful response of the state to the strike is affecting their physical and mental health.

Harale was among the more than 200,000 Anganwadi workers in Maharashtra who have been protesting against the terms of their employment since December 3, 2023. They are demanding that they be designated as regular government employees, paid better wages and granted benefits such as a steady pension, gratuity, provident fund, and health insurance. Currently, a worker (sevika) is Rs 10,500 a month and a helper, Rs 5,500. Once they retire they are given a lump sum – Rs 1 lakh to Anganwadi workers and Rs 75,000 to helpers.

Workers are demanding that they be given new mobile phones to collate and record data related to their duties, better infrastructure for Anganwadis, more nutrition grant per beneficiary and timely recruitment to vacant positions.

The strike has resulted in the shutting down of at least 95% of the state’s Anganwadis, the loss of a month’s salary for protesting workers and also termination of service for many, according to Madhuri Kshirsagar, a Parbhani-based lawyer who heads the Maharashtra State Anganwadi, Balwadi Karmachari Union (AITUC) who is leading the protest. “We are constantly having internal dialogues, meetings and thinking about the challenges but we are firm about the strike unless the government agrees to our demands and makes it official,” she said.

In Andhra Pradesh too, around 1,00,000 Anganwadi workers have been protesting for the last 27 days, seeking better wages and social security benefits, promised by the state government but not fulfilled yet. Workers say they are determined to continue the strike unless demands are met, However, the state has invoked the Essential Services Maintenance Act against protesting workers.

Terminations, Notices

On January 3, lakhs of workers from across the state marched to Mumbai to protest at the Azad Maidan. However, after the government stepped in with some assurance, the workers called off the Azad Maidan protest, returned to their districts and resumed the strike on January 5.

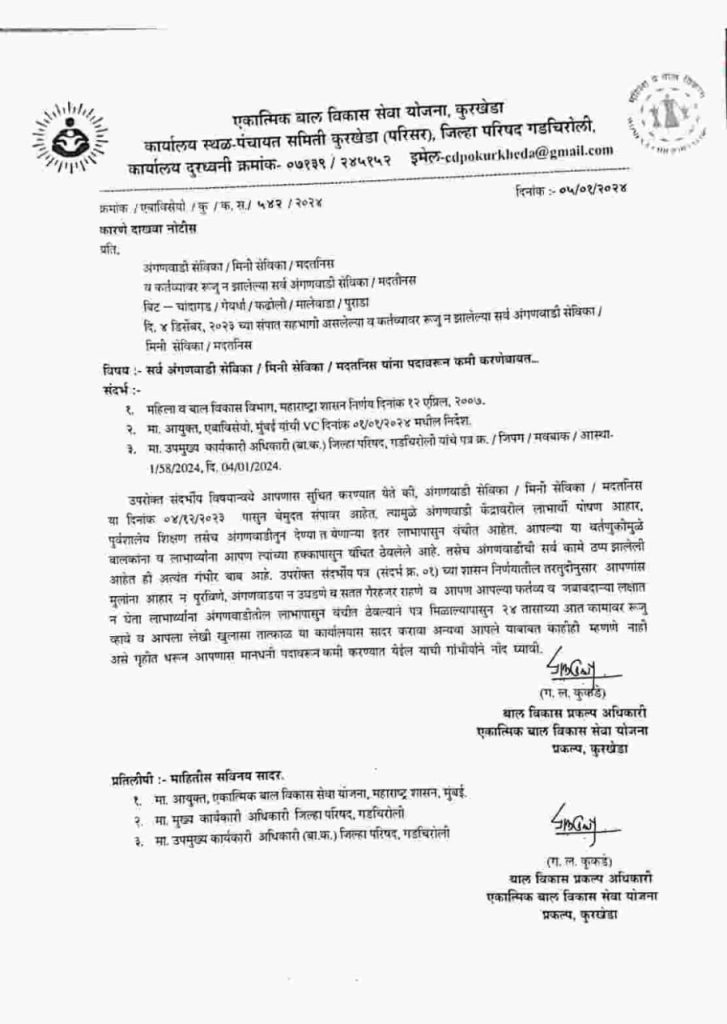

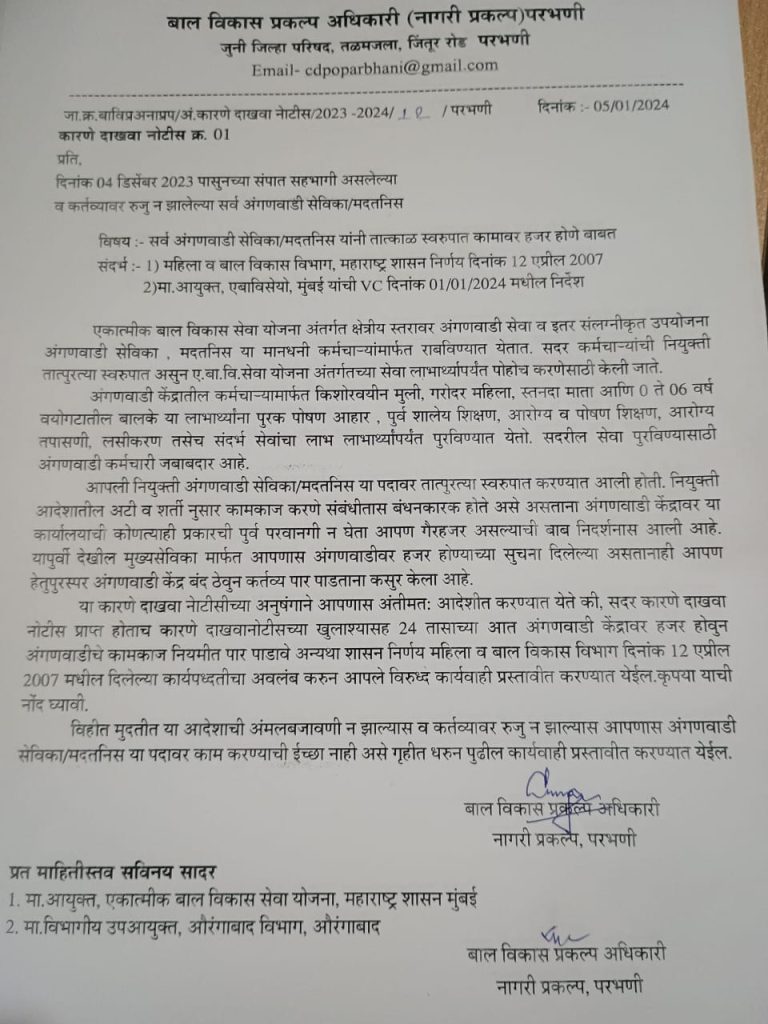

The crisis has now escalated with the Women and Child Development (WCD) department terminating the service of 200 Anganwadi workers in Amravati district and threatening hundreds in Sindhudurg with termination if they do not return to work. The workers responded to the threat by burning the notices in public last week. Workers have also been summoned through show cause notices from the Women and child development department.

Behanbox has access to these notices.

A supervisor who handles 25-30 workers in urban Parbhani denied issuing personal notices to workers but said these have been shared on Whatsapp groups. “Which isn’t saying that workers will be terminated but there would be some action against them. I have just forwarded a notice sent to us by the Child development project officer (CDPO) to the Whatsapp group of sevikas,” she said.

Workers allege that the government has responded callously to their condition.

A month past Harale’s death, no one from the WCD department has visited the family. They have also not been informed when her nominee will be given her post-retirement benefit of Rs 1 lakh.

Behanbox contacted Suman Berje, the WCD supervisor Harale reported to, on this. We also asked what her department was doing about the stressful work conditions of Angangwadi workers that could have worsened Harale’s health, mental and physical.

“Harale’s brother gave us a copy of her death certificate when they visited our office to enquire about her retirement benefits. We are currently processing the documents,” said Berje. She said the delay is being caused by the fact her office is yet to get documents such as the Aadhaar card, the PAN card etc and so on.

The supervisor said she knew of no measures to deal with the stress issues of Anganwadi workers. “You need to ask this to the child development project officer (CDPO),” she said. The CDPO, Milind Waghmare, said he needed to look into the issue to respond to our questions

‘After A Lifetime Of Service, No Dignity’

“No supervisor or any other official came for her funeral or later even to console the family members. Is this what a sevika deserves after a life of dignified service?” said an Anganwadi worker, who has known Harale for years but did not wish to be identified.

Anjanabai, 50 an Anganwadi helper from Hingna block in Parbhani died on January 7. An Anganwadi worker from the block who did not wish to be identified said Anjanabai had participated in the strike and had feared that she would lose her job.

“We started getting threatening notices from the WCD department which said that we may have to face repercussions for our protest. We have already lost one months’ [December] salary because of the strike,” the worker said.

Sangeeta Aananda Jadhav, 60 who was working as a helper at an Anganwadi in Nawali village of Panhala block of Kolhapur died on January 3. She was leaving home for the protest at Azad Maidan in Mumbai but collapsed after complaining of chest pain brought on by a cardiac arrest. Jadhav had a four-year history of diabetes and cardiac issues, said her colleagues.

Jadhav has been working since 2002 and the last salary she received was Rs 5,500.

“These workers are coping with the stress brought on by the intimidating letters sent by the WCD,” said Kshirsagar. “A lot of them are single women — widows, abandoned, orphans and so on. How will they survive if they lose their jobs? The government promises but does not deliver on the issues of pension.”

Women are facing economic hardships because they will not be paid a salary for December 2023. “Women are finding it hard to continue the strike. One of them, desperate for money, reopened her Anganwadi. Infuriated colleagues who are still striking work rushed to her home to demand that she delete her post on the reopening of her Anganwadi. She broke down and showed them the empty food bins in her kitchen. She had nothing to feed her children,” recounted an activist from Parbhani.

Behanbox tried to reach out to Aditi Tatkare, the state WCD minister, on phone and sent her a list of questions on the issues of Anganwadi workers, but the minister has yet to respond.

Exhausting Workload

Jyoti Gaikwad, 38, has been working as an Aanganwadi sevika for the last 11 years in Naigaon village of Paithan in Chatrapati Sambhaji Nagar (formerly Aurangabad). She has three postgraduate degrees – in Marathi literature, social work and Phule-Ambedkar Thought. She set up Anganwadi because she felt she could make a difference to early childhood development.

“But after I joined, I have participated in hundreds of agitations but our demands were never taken seriously. After 12 years of work, I get Rs 10,530 a month. After AITUC fought relentlessly, it was declared that there would be a 3% increment in our salaries after 10 years of work, 4 % after 20 years, and 5 % after 30 years. We don’t get annual increments or bonus; there is no provident fund, gratuity, or pension. I also know of retirees who have not been paid their one-time post-retirement benefit,” she said.

The average inflation rate in India is around 6 % annually, but this is not reflected in the salaries of Anganwadi workers.

Behanbox has reported about the exhausting workload Anganwadi workers have to deal with, especially since the digitisation of the data they collect.

For the 300,00 Anganwadi workers in Maharashtra the workday spills well over eight hours. “We conduct preschool for two hours, then spend an hour cleaning and distributing food – khichadi, lapasi, usal and so on. Then we have to conduct home visits for family surveys, vaccination, registration of births and deaths, and providing take-home rations to pregnant and breastfeeding women. We need to provide them with basic counselling and awareness about health and nutrition. We also need to provide rations at home to adolescent girls who have dropped out of school, provide them counselling and information about government schemes. We maintain 11 types of registers,” said Gaikwad.

Sevikas also work to prevent child marriage among teens who have dropped out of school. “I constantly have dialogue with parents and try to convince them not to stop educating girls. We also take on tasks that are invisible and rarely appreciated,” said Gaikwad.

Anganwadi workers also have to present in events and meetings related to their work. “VIP guests who come for just 15 minutes for the programme get everything, water, good food and luxury hotels, while we are not even offered a glass of water. But we are the first to be called if an official is visiting a village,” Gaikwad said.

Spending From Their Own Pockets

Anganwadi workers have to submit an MPR (monthly progress report) twice a month at meetings that are generally held at CDPO’s office for which they may have to travel between 5-50 km. The travel allowance of Rs 120 is barely sufficient, workers said. They also get Rs 2000 annual allowance for buying cleaning material, stationary, and toys for children. And on Diwali, they are paid a fixed sum of Rs 2000.

“Rs 2000 for miscellaneous expenses is very less. One register costs us Rs 200 to 250 and we maintain 11,” said Gaikwad. “We also pay for the repair cost of the weighing scales many times from our pockets. I have given in an application to my supervisor three months ago for a new or repaired weighing scale for babies up to 3 years of age because the current one is faulty. I got no response. We have to grade children every month and send data before every 5th of the month, otherwise our salary doesn’t get processed. We are compelled to fill in random numbers. We feel guilty, these are like our own children, but what do I do?” said an Anganwadi worker who did not wish to be named.

All the Anganwadi workers we interviewed spend money out of their own pocket whenever necessary. Another worker from Marathwada said they get Rs 250 to conduct meetings with the women of the village to raise awareness about maternal and child health care. “We are supposed to give tea and snacks to 30/40 women who gathered for a meeting. But reimbursements take 6-8 months,” said a worker who did not wish to be named.

The expense per child is Rs 8 per day. And this is supposed to provide fresh cooked food such as khichadi, boiled sprouts, daliya and a handful of dry snacks such as peanuts and jaggery, rajgira laddu, chikki, roasted chana, banana and so on. Workers who prefer to get dry foodgrains from the government, get Rs 0.65 per head as the cost of preparation and distribution.

“I have 80 children at my Anganwadi, so I get Rs 52 everyday for preparing food for 80 children. Gas cylinders cost more than Rs 1000 a month, then we have to buy spices like coriander and chillies which I buy from my pocket,” pointed out a worker from Nanded district.

“This is not voluntary social work. We are contributing to public health, pre primary education of underprivileged children and the overall development of villages. All this needs skills, calibre and energy. We are done with being called ‘sevika’ and being paid an ‘honorarium.’ We are workers and we demand salaries, social security benefits,” said Gaikwad.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.