Why Bastar’s Young Adivasi Women Struggle For A University Education

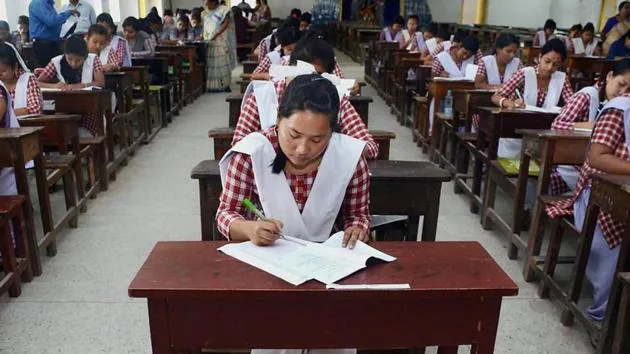

It is difficult for young Adivasis to leave home and head for neighbouring towns or far metros to join universities. For the women, these challenges are multiplied by fear of the city and social biases

Women’s enrollment into research courses in Indian institutes like Jawaharlal Nehru University has already seen a decline since the introduction of the standardised Common University Entrance Test (CUET) and the discontinuation of the MPhil programme after the implementation of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

Ever since I started my fieldwork in 2021 in Bastar, I have been mentoring Adivasi youth about their academic journeys. This mentoring involved tutoring college-bound youths in Sociology, appraising them of future career and academic opportunities, and helping them prepare for entrance examinations. These sessions morphed into online weekly sessions once I moved back to my university in the USA after completing fieldwork.

In the last two years, four of these youths were successful in securing seats in central universities: two joined the Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya (Mahatma Gandhi International Hindi University, MGAHV) in Wardha, Maharashtra in 2022, another has been selected for a Bachelor’s programme in the Indira Gandhi National Tribal University in Madhya Pradesh and yet, another secured a fully funded seat in the Azim Premji University’s Bhopal campus.

While we celebrated their success, during a discussion it dawned on us that those who could travel (with economic, logistical, and moral support) outside Chhattisgarh, or even Bastar, for an education were all men. It is undeniable that Adivasi communities, especially in central India, face several hurdles in accessing institutions of higher education. Yet, Adivasi women face harsher realities in even getting to a regular college, much less in appearing for competitive examinations like CUET.

Most young women I know have opted to complete their undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in ‘private’ where they can appear for exams without having to undergo in-person coursework. These students spend their time preparing for local competitive exams like nursing, teacher training, or public service commissions. All of these exams lead towards an immediate professional career or employment opportunities in the public sector.

In our last conversation over WhatsApp, Sharmila (name changed) and I agreed that it is best for her to appear for MA (Hindi) exams in “private” because she was required to stay at home for care duties. Sharmila’s mother has been ill for over a year, and her sister, being married, leaves Sharmila to do the household chores and agricultural work required to sustain their family.

I have known Sharmila since she was an undergraduate student at the local district college. She was enrolled in the BA (Sociology) programme. Having studied in the celebrated Mata Rukmini Ashram School for Girls, Jagdalpur, Sharmila is well-versed in articulating the social issues faced by Adivasis, particularly the women, of Bastar. Hailing from a village in Sukma, Sharmila was picked by her local school teacher who thought studying at a high school in a town would be beneficial for Sharmila.

It is no doubt a privilege to be able to continue education and employment in the city in which one is born. Not many are born with that privilege. Apart from students from a handful of metro cities, leaving home for education and employment opportunities defines the internal migration scene in India, especially for those from small towns and rural pockets. Migrating from rural India to urban institutes for academic purposes defined most of my teen and adult life.

In the book Migrant Academics’ Narratives of Precarity and Resilience in Europe, edited by Olga Burlyuk and Ladan Rahbari (2023), the authors, predominantly from the Global South, share autobiographical stories of aspirations, desires, sacrifices, precarity and resilience of the academics who have travelled from different regions of the global south to Western academic spaces. The authors have migrated due to varying reasons including war and war-induced instability in the origin-nations, or they have sought better living conditions and well-being.

In contrast to cross-border migration for education and academic employment, the internal migration among the Indigenous people of Northeast India is described in the book Leaving the Land by Dolly Kikon and Bengt Karlsson. The authors deploy the term “indigenous migrants” to refer to “the movement of people who would otherwise be perceived as holding on to their land and livelihoods or being attached to their lands”.

Similar to the indigenous people of Northeast, Adivasis from central India are attached to their lands and livelihood for subsistence agriculture. However, unlike the youth from the Northeast, seasonal migration for employment among the children and youth of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha has a long history. These migrations up until recently have been predominantly for work in the unorganised sectors like agricultural farmhands, manual-construction work, small-scale industries, and as domestic workers in metro cities. Many Adivasi communities from these areas have travelled as far as Assam to work in tea plantations as wage labourers.

While Adivasi communities from Jharkhand and Indigenous Tribes of the Northeast have been travelling to India’s metro cities for higher education, it is a recent phenomenon for many Adivasi communities in Chhattisgarh, especially those who are from Bastar.

Plight Of Bastar’s Higher Education Institutions

Over the last decade, the Chhattisgarh government has done a commendable job of creating educational spaces for Adivasi youths up to high school. Higher education, however, is still an afterthought for policy makers and private actors. Most high school girls I interacted with for my doctoral research had very limited options to pursue after high school, if at all they manage to finish schooling and not drop out due to work/care responsibilities. Most of these options revolved around getting a ‘sarkari’ (government) job. When these students inquired about my academic journey, they were amused to consider the possibility of pursuing higher education without an immediate career goal.

Here, it is not my intention to deride students for not knowing their academic options after high school. The higher education scenario for Adivasi in Bastar is in a dire state. Daso, a student in a government PG college in Kondagaon, asks in frustration: “Who do we approach if there are not enough teachers for even core subjects in our college? Most of our time is spent in asking the administration to hold regular classes.”

The seven districts comprising the Bastar province have 45 government and private colleges, and of them 10 are institutes of trade providing industrial training (ITI, agriculture, and livelihood colleges), one is a university, one an engineering college, one a medical college, and one a nursing college. There are two private colleges. Many of the remaining colleges offer generic BA and BSc courses with no specialisations. Even in courses like BSc (Political Science), BSc (History), BCom, and BSc (Sociology), many lack an adequate number of teaching staff.

During my stay in the area in 2021-22, many college students would report attending only language (Sanskrit or Hindi) classes – for weeks there would be no classes for core subjects like History. Now, many colleges are being used as polling stations for the upcoming assembly election in Chhattisgarh, adding to the frustration of the students.

Among the 45 institutes, two private colleges and one government college offer education in English as the medium of instruction, and the rest are “Hindi-medium” colleges. The medium of instruction further limits students’ options of studying in central universities while it also impacts their test results in the CUET exams, as most universities offer courses with English as the medium of instruction.

It might sound intuitive to think that Hindi as the medium of instruction would help Adivasi youth in Chhattisgarh, where Hindi is used in official documentation in the affairs of the state. But it is important to note that Hindi is not the first language of Adivasis in Bastar. Insistence on Hindi-medium schools, in fact, impairs Adivasi students’ opportunities in getting higher education outside Chhattisgarh. Of the 56 central universities in India, very few offer Hindi as the medium of instruction. Adivasi students from Hindi, and other vernacular mediums, then, are systematically marginalised in central universities and from the processes of knowledge production.

Among the existing colleges, the trade institutes are in block headquarters, all the remaining are in district headquarters and particularly inaccessible to students from villages, some as far away as 80-100 km. A student coming from a village in Konta has to come to the Shaheed Bapurao College in Sukma, a distance of about 70-80 km, to study any undergraduate course. Since commuting every day is not an option, students either take a room in a public hostel or stay in a rented accommodation, unaffordable for most college students. One such student, Ayte, who secured a seat in the BCom course at the college and also an accommodation in the girls’ hostel, had to drop out of the course for many reasons. One was that the hostel had installed CCTV cameras in the dining and bathing areas of the hostel.

Gender-Specific Challenges

There are also multiple gender-specific factors that impair women’s quest for higher education. In our monthly group call, the college students from Bastar share these and their frustrations with the education system.

Gayatri, a student pursuing MA (Hindi) in ‘private,’ starts with the well-known discourse of how women are ‘needed’ at home to do household chores. Joga and Hidma, MA (Sociology) students at MGAHV, reiterate the popular discourse among their relatives – “Ladki hai, sasural jaegi, kisi aur ke ghar chulha phukegi. Padhai karke kya karegi, ham iske padhai me kharcha nahi karenge (Girls will go to their husband’s home, cook and care for his family. What will she do with a college education? We will not spend on her education).”

After extended conversations, the students share other reasons typical to Bastar’s Adivasi communities as they also realise the need for an in-depth understanding of this patriarchal belief which advocates that “girls do not need education”. Gayatri says there is a general consensus over this discourse in their villages though the girls do not lack the motivation to explore higher education. But it is often the extended family that influences parental decisions related to girls’ education.

Joga chimes in to say that restrictions are also imposed on boys, giving his own example. He says: “My family was very sceptical about the prospect of me leaving home or even the state to do an MA in Sociology. They tried very hard to convince me to stay home and join the police department (one of the only available employment for youth in Bastar). It took me many weeks to convince them, and I even had to miss a few weeks of classes before I could leave home to study.”

Being a male, it was not impossible for him to convince his family compared to his two sisters, who have both had to drop out of college and school, respectively. His youngest sister discontinued schooling soon after their father died and became the breadwinner of the family. Now, she thinks it is too late to go back to school. The other sister is preparing for a competitive examination from home. She had multiple backlogs in her BCom examination, and she had to repeat a year. Now, she will take her Bachelor’s exam in ‘private.’ This way, she can be at home to take care of their ailing mother.

Several Adivasi young women like Joga’s sister and Sharmilla discontinue regular college to perform care duties at home. Hailing from areas that have been in protracted conflict over natural resources and governance ideologies, many of these students have lost one or both parents either to conflict or illnesses. Many of their elders are unwell because of the lack of health infrastructure, clean drinking water, water and agricultural produce contaminated with mining wastes, and years of manual agricultural and forest-based livelihood work in adverse weather conditions where malaria, dengue, and TB infection rates are relatively higher than in other parts of the country.

Structural Issues

Discussions on the gendered nature of care work led us to discuss how women are expected to do all the household chores. Hidma says: “Even when I fetch water from the handpump or do dishes, or sweep the house, if any of our neighbours see us, they immediately ask: where is your mother? Why are you doing women’s work? It feels as if the older generation does not want to get rid of the age-old traditional division of labour among men and women.”

Hidma points out that as first-generation students, they lack guidance and awareness. “Before we met you, we had no idea of the central universities. I have tried to motivate a few youths from my village to apply for entrance examinations to these universities. But I don’t know whether it is because of the break in regular education during COVID-19 or because of the pressure from families, youths did not feel confident to even apply,” he says.

Hidma believes that studying in central universities and travelling to other states have helped him gain exposure and understand how communities in other states live and struggle for their rights. Says Gayatri: “Most of the time, our families are also afraid to send us away from villages, especially to far off cities or towns in other states as the idea of travelling outside Bastar instil fear in them.”

During fieldwork, I learned that women and girls who travel far from homes for work – women and girls to pick chilies and young men to work at construction sites, paper mills, and even in automobile repair and wash shops – do not go alone. They are taken in a group by a contractor or a group from the same hamlet travels together to worksites to which they have already been introduced. Young girls go with adult women to farms to work as agricultural workers.

Even when they go to the neighbouring states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana to work as seasonal farmhands, they go in groups, says Joga. “We also hear many stories of Adivasi women getting raped or trafficked, and these stories instill fear among our parents in sending girls to colleges in places that they have not heard of,” he says.

Rachna aunty (name changed), one of my hosts during fieldwork and an empowered ex-sarpanch in the Chhindgarh block of Sukma, had stayed in a rented house in Jagdalpur town for her daughters’ education. During this time her husband stayed in their ancestral village where he continued his teaching job. Only when her three daughters graduated from their respective MA and BEd courses did aunty return to her village. Even then, she still travels to Jagdalpur town to be with her youngest daughter, Tanu (name changed), who is preparing for the Chhattisgarh State’s public service commission examination. When I visited them last summer, mother and daughter had an argument over Tanu’s decision to go to Delhi to prepare for the Union Public Service Commission examination. She could not convince her mother as the family feared she would be exploited in a metro city.

The students in the group-call confirm that if a girl wants to travel for education, first, the family would be afraid to send her alone to any town, near or far. Second, a member of the family, even if it is a younger brother, would have to accompany her to the institute and ensure that she settles in. It becomes hard for families to pay for two family members to travel out of Bastar. Universities often refund tuition fees and do not charge lodging fees for Adivasi students under affirmative action or reservation for Scheduled Tribes students. But, the cost of travel, food and lodging for an extra person is enough to deter the family from deciding in favour of girls’ education. Not to mention the fear of unknown and unwelcoming spaces.

The youth in the group agreed that it is primarily through dialogues with elders and by taking a ‘bit of risk’ that they deal with these challenges. We observed that on the one hand, the structures are almost already preventing young men, and especially women, from pursuing higher education and on the other hand, the existing support systems — in both the administration and the community – are yet to come together to enable girls’ entry into higher education.

(This essay was developed based on a series of conversations in my study group with Bastar’s Adivasi youths – Podiyami Joga, Vanjami Hidma, Mudavi Kosa, Kunjam Gayatri, and Vetti Hidma.)

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.