For These Women Running Public Toilets In Mumbai, The Workday Lasts 15 Exhausting Hours

On World Toilet Day, here are the stories of two women who struggle to keep sanitation complexes in the slums of Mumbai clean and safe

- Priyanka Tupe

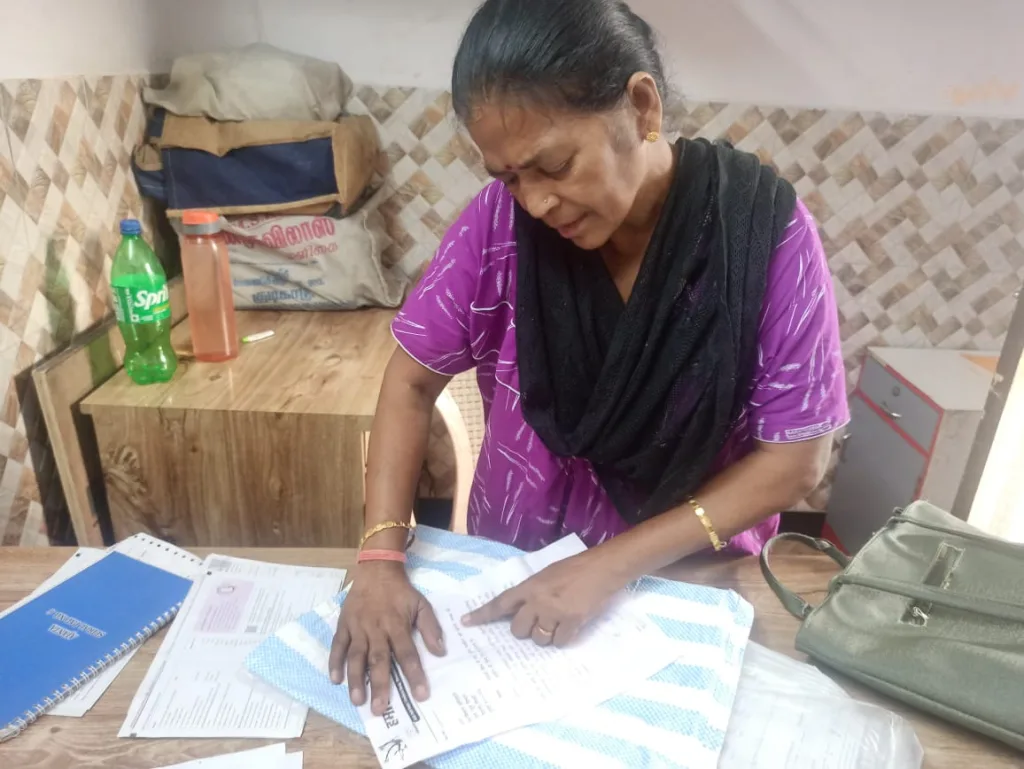

Mumbadevi Kanade, 50, cannot remember when she last slept for six straight hours. Her day begins at 3am as she opens the public toilet in the Dutt Nagar-Lumbini Baug area of Govandi in east Mumbai.

Through the day, her tasks never end: she is cleaning the toilets, collecting cash from users, writing tirelessly to Adani Electricity seeking bill waivers and seeking more support from corporation officers.

Kanade has little education – she could only study up to Class 3. But she is passionate about community work and is fearlessly outspoken. Kanade has lived for 50 years in a slum and she knows the many civic issues that basti dwellers face.

The toilet complex run by Kanade has 18 seats, nine for men and eight for women and one seat for people with disabilities. She charges users Rs 3 per visit.

Kanade started working with the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS), soon after the political party was started by Raj Thackeray in 2009. Her task was to help the people in her area with hospital admission and medical treatment with the resources pulled from various donors. Five years later, she left the party, disillusioned with its politics.

In 2019, she started correspondence with the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) seeking a new toilet in Dutt Nagar, as the older one had become dangerous. “The walls had cracks, the toilet seats were broken. But the process of getting the BMC to agree to a new toilet was exhausting. If a woman steps into a role they are not supposed to, people simply don’t allow them to work,” says Kanade.

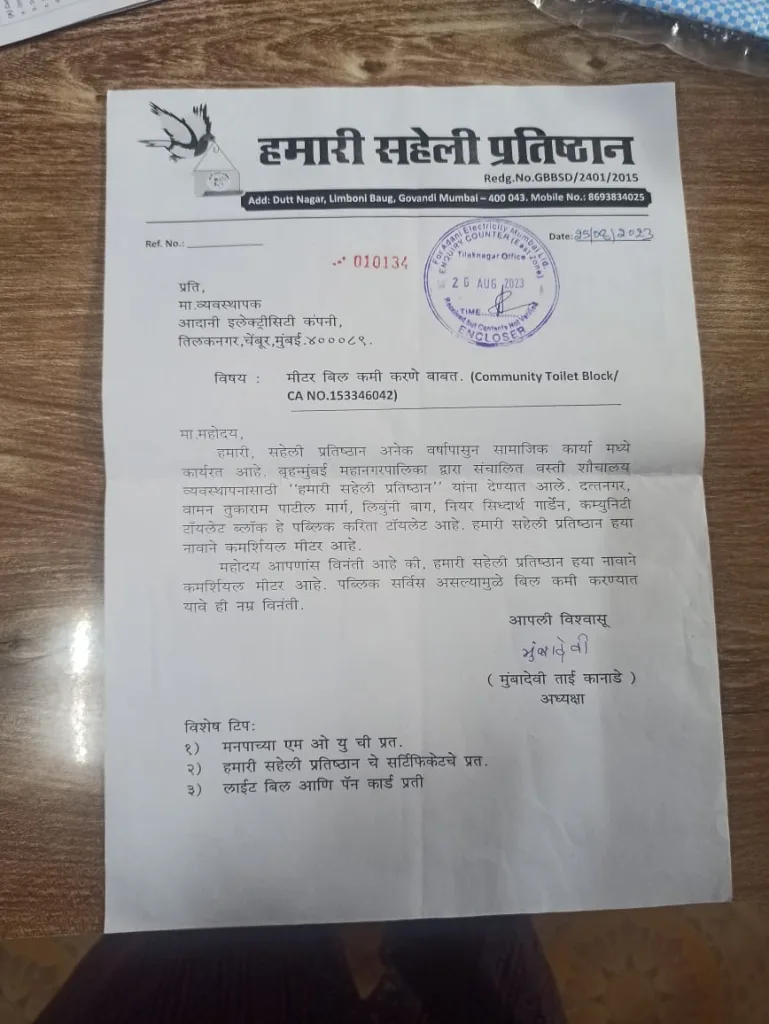

Kanade registered her community based organisation (CBO), Hamari Saheli Pratishthan, in 2019 and demanded a new toilet and the contract to maintain it. A local journalist Rakesh Chandra helped her register the organisation. Some men in her area too were vying for the contract to operate the toilet. “When I started collecting signatures from the citizens in my area to present a demand charter to the BMC, few powerful men opposed us in every way possible. I was threatened and there was an attempt to attack me, but I kept fighting,” she says.

Nearly half of Mumbai’s population lives in densely populated bastis that depend heavily on state-run public toilets which are often badly maintained. It was to tackle this massive challenge that the World Bank-initiated Slum Sanitation Programme was launched in 1995. Under this, CBOs, like the one operated by Kanade, own and run public toilets that are built by the BMC either by reconstructing older, dilapidated structures or by setting up new ones. Unlike the larger chunk of the city’s toilets (65%), earlier constructed by MHADA, the state’s housing authority, CBO-run toilets are not free and the operators can charge between Rs 2 and Rs 10 per use or charge a monthly rate between Rs 60 and Rs 200 per family. Maharashtra Times recently reported that all public toilets will now be run by the BMC.

There are 8,000 SSP toilet complexes in Mumbai, according to BMC’s recent data. We bring you profiles of two toilets operated by women-led community initiatives – Kanade and Kavita Khomane. In conversations with them at their workplace, we found the huge challenges they face in maintaining these overworked facilities which are too few in number.

‘I Clean The Toilets Myself’

As a visit to any public toilet shows, keeping a sanitation facility clean, well-lit and safe is a huge challenge and we found that the small earnings these women operators make simply does not compensate for the effort they put in.

When the BMC finally constructed a new toilet complex in Dutt Nagar, a local corporator tried to grab all the credit, alleges Kanade. But it was she who followed up on the facility’s quality issues. For instance, there was no toilet for the disabled. “I had to follow up a lot for that. It has one western toilet [the rest are Indian style] and is friendly for senior citizens,” says Kanade, showing us the toilet with excitement.

The entrenched links between caste and purity issues come up often. She had appointed a man with a disability as a cleaner at the toilet a couple of months ago. He was an unemployed man from her neighbourhood and was happy to get the job. But his family was furious and fought with Kanade, using casteist slurs.

“Are we Bhangis? Do we look like it? We are upper caste people, cleaning toilets is not our job, it’s yours,” said the cleaner’s sister-in-law who eventually persuaded him to stop working at the toilet. “I realised how deep rooted caste notions are even in cities like Mumbai,” says Kanade.

Kanade has had a hard life, she was abandoned by her husband 25 years ago. She works exhausting shifts totalling 15 hours – 3 am to 12pm and then again, 5pm to 11pm and earns Rs 450-500 a day. Recently when she underwent a cataract surgery, she appointed two of her friends to take on the evening shift and handle the cash counter.

“Though two members of Hamari Saheli Pratishthan work here part time, I clean all the toilets by myself, ensure that the water tanks are full, and look after the maintenance work. I end up saving nothing for myself – all my earnings go into paying the electricity and water bills, buying cleaning materials and paying salaries to the part-timers,” she says.

At commercial rates, the electricity needed to run the toilet cost around Rs 5000-6000 a month. The several letters she has written to Adani electricity have got her no response.

Kiran Khanderao is an activist who works with the ‘Right to Pee’ campaign with CORO India. She believes that the toilet complex should be given a discounted power bill. “We have been demanding electricity bills according to residential usage rates for years [for public toilets]. Electricity companies charge at commercial rates though public toilets are categorised as essential services, not profit-making businesses. These bills are a huge part of the toilet operator’s expenses. The contractors and other stakeholders involved in the construction of the toilets make money through corrupt practices while those who actually operate them day and night hardly get anything,” she says.

Kanade also gets the maintenance work done for the toilets such as dealing with clogged pots, repairing septic tanks, slabs, doors and broken taps, all using her own savings from an income that rarely exceeds Rs 15,000 a month.

“I repaired pipelines, put up sign boards and instructions on how to use the toilets, and put up an awning to protect people from rain and sun. I spent almost Rs 60,000 until now taking a personal loan that I am not sure when and I will repay. People need these basic facilities. It was the contractor’s duty to maintain toilets for five years after construction, but they don’t show up ever and we don’t know where to find them,” she says.

‘I Keep My Toilet Complex Spick And Span’

Kavita Khomane, 42, operates a complex of 10 toilets, four for women, four for men and two for people with disabilities in the Agarwadi area of Mankhurd. Khomane has a different system of operating toilets. She distributes yearly passbooks to the user families in her chawl and does a monthly door- to-door collection. Each family needs to pay Rs 100 for monthly usage of the toilets.

Khomane says she does not make any money running the complex. Her monthly income of Rs 10, 000 to Rs 12,000 , all of which she says is spent on the cleaner’s salary, cleaning material, electricity bills and the quarterly water bill.

“They don’t construct good quality toilets. I spent money from my pocket to repair taps, pipelines, and broken doors of newly constructed toilets. I don’t get any benefits from this work, but it’s my passion,” she says.

She has appointed a man to clean the toilets under her supervision. Everyday she starts work at 5.30 am, dusting, cleaning the premises, ensuring adequate water supply, and keeps an eye on maintenance.

Why run a community facility that brings her no income? “The toilet has deep links with our health so I am contributing to good public health. While our cleaner works on the toilet seats everyday, I clean the premises, windows, and doors. Many times, people spit anywhere in the toilet, they leave them dirty. I feel it’s my responsibility to ensure a hygienic toilet facility for my basti. I don’t have children, pursuing this passion fills the vacuum in my life,” says Khomane.

She could study up to Class 12 because she was married early. But as her register of users shows she has management and documentation skills. The details are entered in her beautiful handwriting and they show passionately she does the job. She also likes drawing, painting and outdoor games.

“I used to participate in every competition in school and bring medals but now everything has changed. I wish I could start painting again. I like to travel, socialise with women for which I usually don’t get time. But this month my team will play a kabaddi tournament in Osmanabad. Everyday I go for a kabaddi practice at 5 pm,” she says.

At the toilet, she has also got a sanitary pad vending and disposal machine installed which is funded by the CSR wing of a private company. She ensures the disposal of discarded sanitary pads twice a week. “Once I start the disposing process, it takes 45 minutes to one hour to complete it. I supervise the entire process, and then disconnect the cables to ensure that children don’t get hurt if they play with them,” says Khomane.

No Support From Civic Bodies

Khomane and Kanade have no fixed salary, health insurance or any other welfare benefits or labour rights.

They are not given the status of sanitation workers though, as per WHO, sanitation work includes emptying toilets, pits and septic tanks; entering manholes and sewers to fix or unblock them; transporting faecal waste; working treatment plants; as well as cleaning public toilets or defecation around homes and businesses.

The BMC is India’s richest civic body with an annual budget of Rs 52,619 crore for financial year 2023-24 but once it outsources the sanitation complexes they hardly do anything to help the operators with maintenance or hygiene. There is an acute shortage of these facilities given the city’s growing slum population and the strain is beginning to tell, according to experts.

“The SSP, a participatory project that initially showed immense potential, is now evidently wilting under its own pressure. It has failed to deliver the promised “ownership” of the community toilets through the symbiotic participation of CBOs, users-slum residents, and civic authorities,” says this September 2023 study by the Observer Research Foundation.

Bezwada Wilson, a national convenor of Safai Karmchari Aandolan, says that it is important that the toilet operators be supported by civic bodies. “Outsourcing the work of cleaning toilets to women’s collectives without giving them a status of sanitation workers and ensuring their labour rights is an exploitation,” he says. “There are enough Supreme Court directives and judgements on this, yet there is no effective implementation. Everyday millions of such workers are exposed to hazardous work conditions.”

Putting Life At Risk

Khomane has to climb to the terrace of the toilet everyday to fill the water tank using a straight iron ladder that has no support or safety railing. Kanade has to clean the choked up toilets and has to manage the the outlets of septic tanks filled with toxic air and substances.

The Right to Pee campaign has been advocating more public toilet facilities and has been working with more than 200 CBOs that operate them. Its activists have been flagging several issues from the safety of sanitation workers to inclusion and gender sensitive approach while constructing toilets. But their suggestions have been ignored by policy makers.

Says Khanderao: “Our suggestions are never taken into account. We provide ideas for inclusiveness, how to make toilets convenient for children, senior citizens, disabled persons, transgender persons.”

There is another important purpose that women-run toilet facilities serve. They encourage women to use public toilets, ensuring their safety by putting a stop to threatening or violent behaviour by male users. “Men often use toilets for substance abuse. They also abuse the women and young girls around them, leaving obscene graffiti on the walls. Women toilet cleaners have to handle all this sensitively and ensure the safety of women users, making them feel secure about visiting these facilities,” says Khanderao.

Many toilets in Mumbai’s M East ward – covering Govandi, the Deonar dumping grounds, Shivaji Nagar and Mankhurd – have not been in use because they are in a state of disrepair and these end up becoming the favoured hang outs of criminals, says Khanderao. Women public toilet operators have managed to change some of this by persisting with the BMC till the toilets are well lit and safe.

Kanade and Khomane have also become politically aware with their experience running the toilets. They now want local corporators to put public toilets issues on their agenda. “These people show up for the inauguration programmes only, otherwise they don’t listen to our demands. In fact, they try to get the toilet construction contracts for their relatives,” says Kanade.

Khomane alleges that she has been harassed, threatened and attacked by goons, some of whom are affiliated to political parties. “I never stepped back. Men think that it’s a profit-making business, but we know what it is. We won’t allow any political leaders to enter our areas unless they take our issues on their agenda and include them in the manifesto during upcoming BMC elections,” she says.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.