Why Odisha’s Adivasi Women Are Trekking Forests And Hills To Collectivise Against A Mining Project

The Sijimali mining project could end up destroying a fragile ecosystem and an entire way of life, say Adivasi women and they are determined to protect them

“You call us illiterate Adivasis. But you are educated and yet you are unable to understand when we say that the Sijimali hill is sacred to us. You continue to sing the same old tune of mining here. So tell us, who is a greater moorkh (fool)? You or us?,” thundered Pushpa Majhi addressing the officials of the mining giant Vedanta and the district administration of Rayagada at a public hearing in Sunger village. The hearing was organised by the Odisha state’s Pollution Control Board for the grant of environmental clearance to a proposed bauxite mining project in the Sijimali block, spanning Rayagada and Kalahandi districts of the state.

Pushpa Majhi had reasons to be angry. The 24-year-old had trekked all night with her 2- year-old on her back from her village Talampadar in Kalahandi district – a full 60 km through dark and dense forests up the hills – to reach Sunger in the Kashipur block of Rayagada district on October 16 to oppose the mining project.

Around 10,000 people had attended the public hearing amidst heavy police and paramilitary presence, a majority of whom were women. Of the 20 residents of the villages affected by mining who took to the podium, 17 were women. The air was tense and there were clashes between the police and the people of the villages who had come for the hearing. Activists say that police stopped and searched, even women, on their way to the hearing.

Two days later, on October 18, Pushpa and her friend Rina Majhi along with 20,000 people, again overwhelmingly women, attended another public hearing on the same project in the Kerpai panchayat office in the Thuamul Rampur Block of Kalahandi district.

In this hearing she brought vegetables and other forest produce in small sal leaf containers and laid them before the officials on the stage.

“Can you tell me what these vegetables are? We are poor people and these vegetables, saga (greens), kandhamula (tubers), ada (ginger), kakudi (cucumbers), chatta (mushrooms) have been our food for centuries. How will we survive without these vegetables?” she asked. “If you have any conscience, then think about how Adivasis and Dalits in this area will survive if you take away our lands and forests for your mines.” The officials were left speechless at her intervention, she told Behanbox over the phone from her village in Kalahandi.

“Sijimali forest land is worshipped as a god. The police have been coming to our village in the middle of the night and scaring us. I want to ask: ‘Are we in a ganatantra (republic) or ‘guntantra’ (rule of the gun/terror),” asked Namita Majhi (19) at the Sunger public hearing.

Bharati Naik, 23, a Dalit woman said at the hearing: “I want to ask our district magistrate, the police, tehsildar, sarpanch ‘When will you come to our area to see our condition?’ Has Vedanta ever come to our area to seek our consent for mining?”

“If you think we are poor, then I ask who is responsible for it? And if you think we are poor Adivasis, then would you come after our livelihoods, our jungle (forests) and jameen (land)?, asked Kanchan Majhi, a 19 year old Adivasi leader from Kantamal village.

A resistance movement has been brewing in the Sijimali hills in Odisha since Vedanta was declared the preferred bidder for the Sijimali bauxite block in February 2023 and women have been leading this movement. In an area where 70% of the population is Scheduled Tribes, primarily Kandha and Paroja communities, and 20% are Scheduled Castes mainly the Dom community, the women fear for the loss of their livelihood, culture and safety. Systemic police crackdown and intimidation of men in the region has thrust women into the forefront, as we detail later. Today, this movement is spearheaded mostly by young Adivasi and Dalit women who are students, mothers, agriculture workers and collectors of forest produce.

Why Sijimali Opposes The Mine

The Sijimali Bauxite Mining Project spreads across Thuamul Rampur block in Kalahandi district and the Kashipur block in Rayagada district. It will affect 18 villages, 8 in Rayagada and 10 in Kalahandi according to the Environmental Impact Assessment report prepared by vedanta, though local activists have claimed that it will affect around 50 villages. In February 2023, Vedanta was declared the preferred bidder for the Sijimali bauxite block with estimated reserves of 311 million tonnes of bauxite. Assessment reports suggest that the mining activities will displace 100 families and affect the livelihood of another 500 families.

Critics of the mining project allege that the state government is violating the Forest Rights Act 2006 and the Land Acquisition Act 2013. The Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) (PESA) Act, 1996, and the Right To Fair Compensation And Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement Act, 2013 which clearly state that the Gram Sabha or Panchayat should be consulted before land acquisition in tribal majority areas.

In a letter to the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST) in February, retired bureaucrat EAS Sarma wrote: “Under PESA and FRA, no private mining can be allowed in this area without a prior discussion and consent by the Gram Sabhas, supported by a resolution of the Odisha Tribal Advisory Council. It appears that the concerned authorities are not in compliance with that statutory requirement, which renders allotment of the mine to any private party illegal.”

Additionally, Vedanta also seeks to acquire 128 hectares of private land for the project, in violation of the Orissa Scheduled Areas Transfer of Immovable Property (By Scheduled Tribes) Regulation, 1956, which prohibits transfer of land and minerals in Schedule V areas of the state to private parties, and in contravention of the Supreme Court’s landmark Samatha vs State Of Andhra Pradesh And Ors verdict in July 1997. It is important to note that the new Forest Conservation Rules 2022 has eliminated the constitutional and legal provision of seeking consent from the gram sabhas for any projects in their areas, liberalised norms for diversion of forest lands, promoted privatisation of forests and gave more powers to the centre to dilute the rights of the state governments over forests governance. In addition the amended Rules also remodelled the afforestation scheme to encourage the raising of private plantations, including for commercial use.

Apart from the environmental damage and loss of livelihoods, the Adivasi community is angry at the deliberate omission of the socio-cultural losses experienced by the communities in the draft Environmental Impact Assessment report submitted by Vedanta.

“Villagers pointed out that Vedanta’s report does not mention the sacred abode of the supreme deity of the Kandha and Damba communities, Tiji Raja, and the annual rituals and festivals the local people perform at Sijimali hilltop in December every year,” said the statement released by the Sijimali Suraksha Samiti.

The Samiti also pointed out that the report makes no mention of the “200-odd perennial streams that emerge from Sijimali or the dense forests on the hilltop that have diverse tree species like sal, tamarind, piya sal, aamla, harida, bahada” and omits the fact that “the collection of siali leaves and honey is the major source of local peoples’ Non Timber Forest Produce (NTFP) income.”

Additionally, the Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) of the environment ministry has pointed out that at least two villages affected by the project fall within the notified eco-sensitive zone of the Karlapat Wildlife Sanctuary. The company has refuted this.

The Resistance

The resistance against Vedanta’s mining project began on March 1, 2023, a week after the company was declared the preferred bidder in an auction. About 5000 Adivasis, Dalits, and Bahujans formed the Sijimali Surakhsa Samiti (SSS), a campaign group, as they gathered on the Sijimali hill in Kalahandi district, said Madhusdan, a member of the Mulniwasi Samaj Sewak Sangh, a grassroots group of Adivasis, Dalits and Bahujans, that is part of the resistance movement.

Rina Majhi, 24, of Talampadar village in Kalahandi district has been part of the SSS since day one.

“This hill has given us everything. It has sustained us through droughts and diseases. How will we survive after the company comes? This is why we started the resistance movement,” she told Behanbox. Rina moved to Kalahandi from Aska in Ganjam district in southern Odisha after marriage. She said she is fighting for the collective futures of all the Adivasi people of the Sijimali hills.

“I may not have been born here but this is where I live now and this is where my grave will be. My kids and theirs will live here. I’m fighting for their future,” she said.

Rina and Pushpa Majhi are young mothers too. Rina is pregnant with her second child and had never walked up a hill before. Yet between August and October, she made intense walking trips to villages, sometimes 4-5 in a day, especially in Rayagada district, since the district needed more mobilising than her native Kalahandi. They have spoken to village elders and anyone who needed to be convinced that the mining project is not just bad for the ecology but also for their livelihoods and safety.

“Even when we would visit villages for creating awareness, these women would give us cover, provide us safety and security from the police”, said Madhusudan.

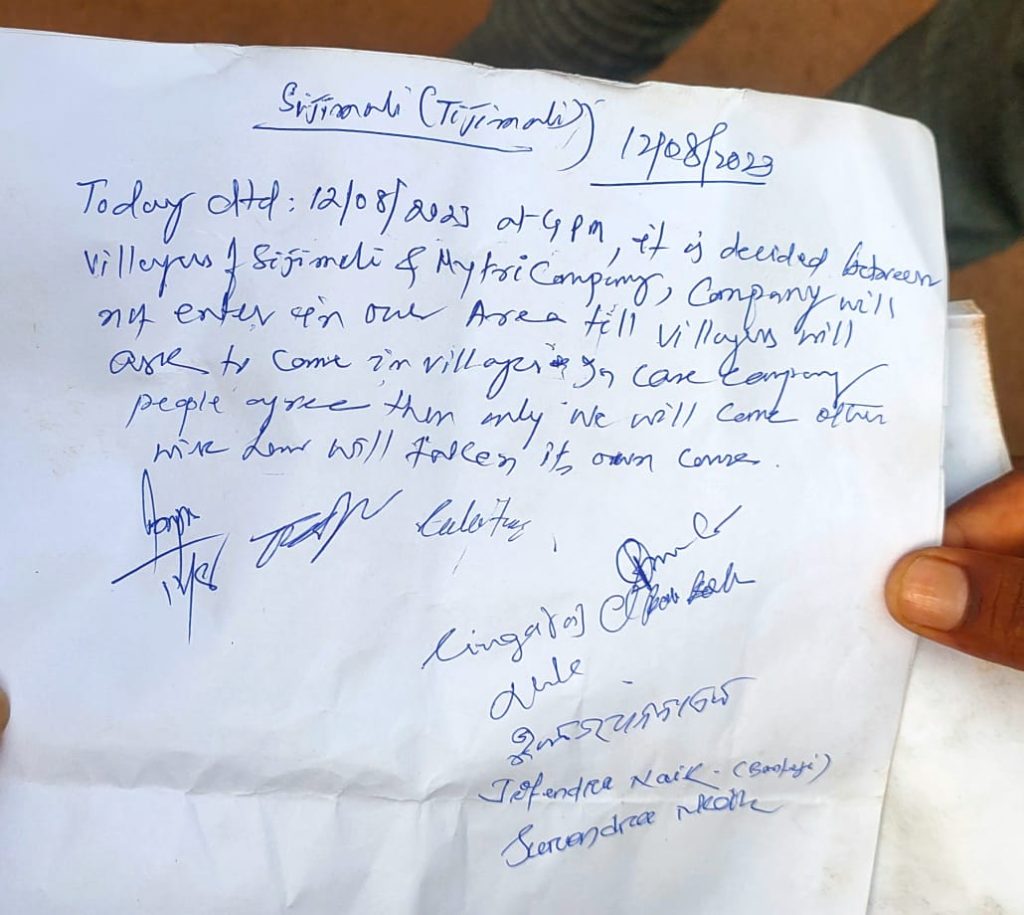

On August 11, when personnel from Vedanta started cutting trees on the road from Sagbari village to Malipadar village, Rina and Pushpa along with other women from the villages protested by sleeping on the road. The company not only had to stop work but these women took a written assurance from the company that they would not enter the area.

Namita Majhi, a first-year nursing student studying in Bhawanipatna, decided to skip her nursing exams and return to her village Kantamal in Kalahandi district to mobilise women and men in her region ahead of the public hearings.

“Parikhya chaadi ki mo maati ku moo boncheiba pai jodi aasi no thanthi, mo mulya kon rahiba? (If I had not skipped my exam to fight for my motherland, then what is my value?),” she said.

She along with childhood friend Kanchan Majhi (19) along with a team of 50 young educated women, all similar ages across the villages in the region, have been leading the resistance. They do not trust Vedanta’s claim of providing jobs to the locals with the advent of the mining operations. In the pre-feasibility report submitted by Vedanta, the company claimed to provide 374 jobs, 277 permanent and 97 temporary ones, a majority of which are highly skilled and project management-related, which aren’t available for locals.

“What kind of jobs will they give us? Will they ask us to sweep floors? Chakiri nahin chakara baniyebe (they will not give us jobs but make us their servants),” said Namita. These women are also not very enthused by Vedanta’s offer of Rs 1500 per month to every household as compensation.

These young women leaders have found support from their families, especially their mothers. Namita Majhi remembers her mother telling her: “Tome doro nain, lodei koro. Tomoko aame bekaar jonmo deyichu ki? (You go ahead and fight. We gave birth to you for a reason).” These elderly women also inspire the youngsters with their tales of resistance against the L&T company who had the previous licence to mine the mountain.

Police Intimidation

This resistance has not been easy for the women – police intimidation, rape and death threats have been plenty, they say. Munidei Majhi, 40, summed up the police intimidation at the Sunger public hearing. “For the past 3 months, the police have been harassing us in our area. Before the public hearing, the police camped at Hatpada Street, Sunger Street, Sarambai Street and stopped all the people, creating an atmosphere of unrest and fear,” she said.

Namita Majhi narrated her ordeal with the police a day before the Sunger public hearing in a conversation with Behanbox. Around 50 policemen came to her village a day before, she said, and told them not to carry their traditional weapons to the hearing. “I asked them why do you carry guns, when we are not allowed what is part of our culture?”

According to her, women police officers threatened to arrest her and slap cases on her and told her: “Aei jhia bohot phutani heuchi (This girl is overstepping her boundaries).”

On October 9, 24 women from Kantamal and Banteji villages, on their way back after visiting a pregnant woman from their village, were intercepted by the police in Bolero cars and threatened with rape, alleges Kanchan. The women filed an FIR with the Kashipur police. (Behanbox has seen a copy of the FIR).

Rina Majhi recalls escaping with other women and her toddler when the police came searching for them.

All women we spoke to alleged that they have received rape threats repeatedly from the police. Besides this, women have also complained about police flying drones over their villages allegedly to identify Naxalites who they suspect of supporting the movement. “Women in our villages bathe in the streams and this affects their privacy,” said Namita Majhi.

Since March, local Adivasi activists opposing the mining project have been intimidated with stop and search procedures conducted on them. FIRs were registered against activists of the Niyamgiri Suraksha Samiti such as Drenju, Krushna, Bari Sikoka, Lingaraj Azad and others under Arms Act and IPC while they were returning after making arrangements for the celebrations of World Indigenous Day. Nine people from the Adivasi community associated with the anti-mining protests in Niyamgiri were booked under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). The Mulniwasi Samaj Sewak Sangh has extensively documented the police action against local activists.

Apart from the activists, police have been intimidating men and young boys from the villages routinely, say all local Adivasi activists that we spoke to. This intimidation of men is one of the main reasons that young women assumed the leadership of the Sijimali resistance, Namita Majhi told us.

“Though we haven’t seen British rule, we have read about it in our textbooks. Today, the police oppress us more than the British, picking us up in the market. Why are the police detaining our elderly people while taking them to the hospital?” asked Bharti Naik to the Rayagada district administration at the public hearing.

Way Forward

The public hearings are a big success, say all the women we spoke to. “Mobilising 20,000 people to attend the public hearing is a victory for us. We collectively stood against the might of the government and the company that has threatened us for the last so many months”, Rina Majhi told Behanbox. On October 29, she along with the other women activists of the Sijimali Suraksha Samiti met at Talampadar for a ‘Bijoy (victory) Rally’, where she emphasised to the hundreds collected there that it was a collective victory. The written and oral testimonies of the residents of the villages falling within the two blocks were submitted after the hearing, where the official from the Odisha pollution control board declared that the final decision would rest with the central and state governments.

However, the women of the movement are not resting. They plan to hold more meetings and direct interactions with those who have not yet come around. At the same time, they are being cautious about the other ways in which the state and the company is trying to obtain consent.

“Now they are trying to obtain consent through ASHA, Anganwadi workers and also through self help groups. So we have told the villagers not to give their ration card, passbooks and Aadhar cards,” said Namita Majhi. They plan to hold their own Palli Sabhas to “drive Vedanta away”, she told us.

What if the government’s decision goes against them, we ask. “Amo mali ku boncheiba pain Palli ru Dilli porjonto jibu (We will march from our village to Delhi if need be to save our hill),” said Rina.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.